Abstract

Differences in the composition of the gut microbial community have been associated with diseases such as obesity, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer (CRC). We used 454 titanium pyrosequencing of the V1–V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene to characterize adherent bacterial communities in mucosal biopsy samples from 33 subjects with adenomas and 38 subjects without adenomas (controls). Biopsy samples from subjects with adenomas had greater numbers of bacteria from 87 taxa than controls; only 5 taxa were more abundant in control samples. The magnitude of the differences in the distal gut microbiota between patients with adenomas and controls was more pronounced than that of any other clinical parameters including obesity, diet or family history of CRC. This suggests that sequence analysis of the microbiota could be used to identify patients at risk for developing adenomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microbes that are associated with the human body outnumber our own ‘human’ cells by a factor of 10 (Savage, 1977) and provide us with a wide array of vital metabolic functions (Gill et al., 2006; Willing et al., 2009). Recent research suggests that disruption of the human microbiome may play a crucial role in diabetes (Burcelin et al., 2009), skin diseases (Grice et al., 2008), obesity (Backhed et al., 2004; Ley et al., 2005, 2006; Turnbaugh et al., 2006; Cani and Delzenne, 2009; Tsukumo et al., 2009; Turnbaugh and Gordon, 2009) and a range of ‘immuno-pathologic’ conditions including inflammatory bowel diseases (Moore and Moore, 1995; Powrie and Uhlig, 2004; Rakoff-Nahoum et al., 2004; Rakoff-Nahoum and Medzhitov, 2006). Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a prevalent malignancy within the western countries and is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States (Jemal et al., 2010). The majority (∼90%) of CRC cases arise sporadically from benign adenomatous polyps (Lance, 1997). There is significant variation in the risk of developing CRC between and within populations and geographical regions (Lance, 1997). Although age, tobacco and alcohol consumption, lack of physical activity and increased body weight are considered important risk factors for CRC (Moore and Moore, 1995), the most significant risk factor appears to be diet (Bingham, 2000).

The role of host-associated microbiota (Hope et al., 2005) has also been frequently proposed as a critical factor in CRC development (Huycke and Gaskins, 2004; Scanlan et al., 2008). Recent technological breakthroughs now allow for the study of the human-associated microbiome at a level of detail that was unimaginable only a few years ago (Margulies et al., 2005; Petrosino et al., 2009). Initial examinations of the human-associated microbial community with next-generation sequencing have discovered enormous inter-personal variation in the microbiomes of healthy individuals (Costello et al., 2009). In this study, we used high-throughput pyrosequencing approaches to ask how the distal gut microbiome varies between individuals who have colorectal adenomas compared with a control group without adenomas. Our results suggest that, despite the tremendous differences between individuals in their associated microbiomes, there is a consistent signature across subjects associated with colorectal adenomas.

Materials and methods

Study participants, colonoscopy and biopsy procedures

To evaluate associations between the gut microbiota and the presence of adenomas anywhere in the colon, we collected biopsies from normal rectal mucosa ∼10–12 cm regions from the anal verge from 33 adenoma subjects and 38 adenoma-free controls. Participants in the study were randomly selected from the Diet and Health Study V, which included persons age 30 years or older who underwent colonoscopy for screening purposes at the University of North Carolina Hospitals. Eligible subjects gave written informed consent to provide colorectal biopsies and a phone interview that asked questions about diet and lifestyle. Information on diet was obtained from a comprehensive, validated, quantitative food frequency questionnaire developed at the National Cancer Institute. A lifestyle questionnaire collected data about demographics, medical history, physical activity, medications and other exposures factors from eligible participants. At the time of the colonoscopy procedure, the research assistant obtained anthropometric measures in order to determine body mass index (BMI) and waist–hip ratio (WHR).

Subjects were in generally good health when they presented for screening. All patients received standard instructions for preparation for colonoscopy that included consumption of 4 l of polyethylene glycol for bowel cleansing. Inclusion criteria included visualization of the entire colon with complete colonoscopy and a clean colon to avoid the misclassification of cases and controls. Exclusion criteria included colitis (either ulcerative, Crohn’s, radiation or infectious colitis, chronic inflammatory illnesses), previous colonic or small bowel resection, previous colon adenomas or colon cancer, sigmoidoscopy or incomplete colonoscopies, familial polyposis syndrome. The enrollment procedure as well as colonoscopy and biopsy procedures are similar to previously described protocols (Keku et al., 2005; Shen et al., 2010).

Subjects were asked if they used antibiotics in the last 3 months before colonoscopy. In all, 33 subjects (11 controls and 22 cases) answered the question. Among these subjects, one case subject (4.55%) and one control subject (9.09%) reported antibiotics use. We have no information about the specific antibiotics they took or why they took them. None of the patient was on antibiotics at the time of the study.

A study pathologist examined all pathologic specimens to confirm adenoma case status and recorded the number of polyps, size, location and histology. Subjects with confirmed adenomatous polyps were classified as cases and those without adenomas as controls. In order to avoid disturbing the mucosa as much as possible, rectal mucosal biopsies were collected immediately after inserting the scope ∼10–12 cm from the anal verge for each patient. The biopsies collected from all subjects were from ‘healthy mucosa’ and not from adenomas. Normal mucosal biopsies were rinsed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline to ensure no contamination with fecal matter and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen on site. The frozen biopsies were later transferred to −80 °C until DNA extraction. The normal rectal biopsies from the study subjects did not show any histology suggesting inflammation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina, School of Medicine (Protocol #05-3138).

DNA extraction and sequencing

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted from mucosal biopsies. The biopsies ranged in weight between 10–20 mg. Two biopsies per subject were used for bacterial DNA extraction and these were placed in lysozyme (30 mg ml−1; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min. The biopsy–lysozyme mixture was homogenized on a bead beater (Biospec Products Inc., Bartlesville, OK, USA) at 4800 r.p.m. for 3 min at room temperature followed by DNA extraction using the Qiagen DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA, cat # 14123) as per the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. The mucosal adherent microbiome was analyzed by Roche (Branford, CT, USA) 454 titanium pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA tags from genomic DNAs. Pyrosequencing (Margulies et al., 2005) was conducted at the University of Nebraska Lincoln Core for Applied Genomics and Ecology. We amplified the V1–V2 region (F8-R357) of the 16S rRNA gene from mucosal biopsies followed by titanium-based pyrosequence analyses. The 16S primers contained the Roche 454 Life Science’s A or B Titanium sequencing adapter (italicized), followed immediately by a unique 8-base barcode sequence (BBBBBBBB) and finally the 5′ end of primer A-8FM, 5′-CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTCGACTCAGBBBBBBBBAGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′ and B-357R, 5′-CCTATCCCCTGTGTGCCTTGGCAGTCTCAGBBBBBBBBCTGCTGCCTYCCGTA-3′. Each DNA sample was amplified with uniquely barcoded primers, which allowed us to mix polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products from many samples in a single run.

Data filtering

Sample filtering

We screened all the samples for a batch effect that correlated with the date of submission to the sequencing center. Samples were shipped on three separate dates from Chapel Hill to the sequencing center in Nebraska. Samples shipped on one particular date (30 September 2009) were found to cluster separately from samples shipped on other dates (10 June 2008 and 21 July 2008). The DNA stocks of these two groups of samples were also stored in different freezers at the Chapel Hill lab (Keku lab, UNC at Chapel Hill, NC, USA). In addition, the sum of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes observed in samples shipped on this date was much lower than we would expect based on both previously published human gut microbial 454 data sets and our own 454 data sets. Sequences generated from samples sent to the sequencing center on this date were therefore removed from further analysis. Leek et al. (2010) recently showed the importance of screening high-throughput data sets for batch effects and screening for batch effects indeed proved useful in removing the technical artifacts from our data set. The characteristics of the 71 samples, selected after sample filtering, are shown in Table 1.

Sequence filtering

Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Pipeline: The first step in the data analysis process involved a preliminary QC (quality control) filter (downstream of the Roche 454 GS-FLX software filtering). We removed sequences from our data set if there were any Ns in the sequence or the 5′ primer did not exactly match the expected 5′ primer or if the average quality score was <20. We then removed the 5′ primer sequence from our reads that have survived above filtering. Only trimmed filtered sequences with a length between 200–500 bp were kept in our data set for RDP analysis.

Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) Pipeline: We removed sequences from inclusion in the OTU data set if there were any Ns in the trimmed sequence or if the 5′ primer did not exactly match the expected 5′ primer. As recommended by Kunin et al. (2010), sequences were end-trimmed with the Lucy algorithm (Chou and Holmes, 2001) at a threshold of 0.002 (quality score of 27). Only reads with trimmed lengths between 150 and 450 were retained for OTU analysis. Table 2 shows the number of sequences removed by our RDP and OTU pipelines.

Bacterial identification

The sequences in our data set were given taxonomic assignments based on two methods.

RDP assignment method: Sequences that have been filtered using the RDP pipeline (Table 2) were submitted to the RDP Classifier 2.1 algorithm for taxonomic identification at various taxonomic levels. Sequences assigned in each sample to various taxa, from phylum level and genus level, were counted at the RDP confidence threshold of 80.

OTU assignment method: OTU analysis is more sensitive to sequencing error (Kunin et al., 2010) and we therefore applied additional QC steps in our OTU analysis pipeline (Table 2). Sequences filtered through the OTU pipeline were submitted to AbundantOTU (http://omics.informatics.indiana.edu/AbundantOTU/) for assignment of each sequence to OTUs (97% identity). Sequences assigned in each sample to various OTUs were counted and then normalized and log transformed (see Data Preprocessing), before proceeding to further downstream analyses. Consensus sequences generated by AbundantOTU during construction of OTUs were submitted to RDP classifier 2.1 to assign taxonomy to each of the OTU groups. Consensus sequences of the 613 OTUs generated by AbundantOTU (Supplementary File 3.txt) were also submitted to ChimeraSlayer (Haas et al., 2011) (http://microbiomeutil.sourceforge.net/) and the nine consensus OTUs identified by chimera slayer as chimeras were removed from our data set. In addition, consensus sequences of four OTUs on BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) search against the Silva reference 16S database failed to match >97% sequence identity, so these were also removed from further analysis. This left a total of 600 OTUs.

Richness and evenness

Shannon–Wiener Diversity Index, H, was calculated using the equation, H=−ΣPi (lnPi), where Pi is the proportion of each species (taxa) in the sample. Richness was calculated as the number of OTUs, genera or phyla observed in 2636 sequences (where 2636 is the number of sequences seen in the sample with the fewest sequences). For each sample, 2636 sequences were randomly chosen 1000 times and the average number of OTUs, genera or phyla observed over these 1000 permutations was reported as richness.

Evenness measures how evenly the individuals are distributed among the different species/taxa and is calculated by J= H’/Log (S) where H’ is Shannon diversity and S is the number of species or taxa in each sample. Wilcoxon-tests and Student’s t-tests were performed to compare the mean similarities of the groups, case and control. The false discovery rate (FDR) was set at 10% using the Benjamini and Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) to avoid type 1 error due to multiple comparisons on a single data set.

Data preprocessing

Raw counts were normalized then log transformed using the normalization scheme mentioned below, before proceeding with the rest of the analyses.

LOG10 ((Raw count/number of sequences in that sample) × Average number of sequences per sample +1).

Removal of rare taxa

In order to minimize the number of null hypotheses for which we need to correct for multiple hypothesis testing, we needed to remove rarely occurring taxa that occurred in so few patients that they could not be significantly associated with case–control or obesity phenotypes. In all of our analyses (except richness calculations), we therefore only included taxa that occurred in at least 25% of all samples. For the RDP approach, 9 phyla and 100 genera met this criterion. For the OTU approach, 371 OTUs met this criterion.

Tree generation

For each of the 371 consensus sequences from OTUs that met the above criteria, BLASTN (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was used to find the top 10 hits in the Silva reference tree release 104 (http://www.arb-silva.de/download/arb-files/). In this way, we identified a set of 3594 aligned sequences to serve as our reference tree. The program align.seqs within MOTHUR (http://www.mothur.org/) was used to align the 371 AbundantOTU consensus sequences that passed all QC steps to these 3594 aligned sequences as extracted from the Silva reference alignment. With custom Java code based on the Archaeopteryx code base (http://www.phylosoft.org/archaeopteryx/), we removed all but the 3594 sequences from the Silva reference tree. We then uploaded the alignment of the 3594 reference sequences plus the 371 AbundantOTU sequences to the RaxXML EPA server (http://i12k-exelixis3.informatik.tu-muenchen.de/raxml), which uses maximum likelihood to place new sequences within a reference tree. Each node in the tree was colored by FDR (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure 4). Trees were visualized with Archaeopteryx. Leaf nodes in Supplementary Figure 4 are labeled with the RDP call of the consensus sequence at 80%.

Data validation

Real-time quantitative PCR validation

qPCR primers were designed based on no <95% sequence similarity from bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA sequence alignments obtained from pyrosequencing. To measure the abundance of a specific taxon, three primer pairs where designed: one generic for all bacterial groups (Universal Primer): [EUB341-F 5′-CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′; EUB518-R 5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-3′] and three taxon-specific primer pairs: first for the Helicobacter genus (Heli_F 5′-AGTGGCGCACGGGTGAGTA-3′; Heli_R 5′-GTGTCCGTTCACCCTCTCA-3′), the next one for the Acidovorax genus (Aci_F 5′-TGCTGACGAGTGGCGAAC-3′ Aci_R 5′-GTGGCTGGTCGTCCTCTC-3′) and another for the Cloacibacterium genus (Clo_F 5′-TGCGGAACACGTGTGCAA-3′; Clo_R 5′-CCGTTACCTCACCAACTAGC-3′).

In all, 10 μ l PCR reactions were prepared containing 100 ng of DNA extracted from colonic mucosal biopsies, 10 μ M of each primer and 5 μ l of Fast-SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cycling conditions were: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 30 s. A single dissociation curve cycle was run as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 min, and 90 °C for 30 s. A pool of samples was prepared to serve as the standard for the qPCR by mixing equal volumes from each sample. Abundance of a specific taxon was calculated by the delta–delta threshold cycle (ΔΔCt) method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) in which: ΔΔCt=(CtTSE – CtUE) – (CtTSP – CtUP)

Where: CtTSE: Ct of experimental samples for taxon-specific primers, CtUE: Ct of experimental samples for universal primer, CtTSP: Ct for DNA Pool for taxon-specific primers, CtUP: Ct for DNA pool for universal primers. Theoretically, the abundance of a taxon is 2−ddCt.

Statistical analyses

The diversity indices, richness and evenness, were calculated using JAVA implementations (see Supplementary File 2). Kruskal–Wallis, Wilcoxon and Student’s t-tests were performed using JMP 8.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) to compare the mean similarities of the groups, case and control. Regression and correlation analyses were performed using JMP 8.0 (SAS Institute) and in R (Open Sourced Statistical software, Vienna, Austria).

Results

We analyzed the adherent microbiota from mucosal biopsies of 33 adenoma cases and 38 non-adenoma controls based on the 16S rDNA genes and high-throughput pyrosequencing methods. Case subjects were slightly older (case 57.4 years) compared with controls (55.7 years). Cases were more likely to have higher WHR than controls (P=0.06) and be overweight or obese (P=0.09). There were no significant differences between cases and controls for smoking, fiber intake, calories, fat and other risk factors (Table 1). The location of the adenomas were proximal (42%), distal (42.5%) and both locations (15.5%). Adenomas were categorized as small (1–5 mm) medium (6–10 mm) and large (>10 mm) with 69.7% classified as small, 24.2% as medium and 6.1% as large. The average number of adenomas in case subjects was 1.6 (range 1–9).

Our initial analyses looked at global signatures of the entire microbial community. At the phylum, genus and OTU (cluster of sequences in which the average percent identity of all of the sequences within a cluster is ⩾97%) levels we found significant differences in richness (that is, the number of taxa present in a sample), but no differences in evenness (that is, how evenly distributed taxa are within a sample), between cases and controls (Figure 1; Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). In order to see whether case samples cluster separately from control samples, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) of the log-normalized abundance of the 371 OTUs that occur in at least 25% of our samples (Figure 2; Supplemental File 1). Results from this unsupervised clustering showed imperfect but statistically significant clustering based on disease status at the global level; a Wilcoxon test performed on the first principle component from this PCA rejected the null hypothesis that case and control had the same distribution with a P-value of 0.0007.

Richness (left panel) and evenness (right panel) for the OTUs observed in our study for cases (n=33) vs controls (n=38). The x axis is proportional to the number of subjects in each category. By the Wilcoxon test, cases had a significantly higher richness (P=0.0061) than controls, but there was no significant difference in evenness (P=0.36).

We next tested which individual bacterial taxa were different between cases and controls. By examining the results of the RDP classification algorithm (Wang et al., 2007) at the phylum level, we observed at a 10% FDR threshold that cases had higher relative abundance of TM7, Cyanobacteria and Verrucomicrobia compared with controls (Supplementary Table 1). At the genus level at a 10% FDR threshold, the relative abundance levels of 30 genera including Acidovorax, Aquabacterium, Cloacibacterium, Helicobacter, Lactococcus, Lactobacillus and Pseudomonas were higher in cases vs controls (Supplementary Table 2). Remarkably, only one genus, Streptococcus, had a higher relative abundance in the control group. In order to validate these pyrosequencing results, we developed qPCR assays for a subset of observed genera that were significantly different in their relative abundances between cases and controls (that is, Helicobacter spp., Acidovorax spp. and Cloacibacteria spp.). We observed the expected correlations between the two methods (Supplementary Figure 3), validating the results of our pyrosequencing approach.

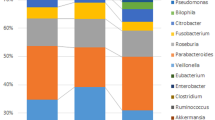

We next performed an analysis of OTUs, which are clusters of sequences in which the average percent identity of all of the sequences within a cluster is ⩾97%. Our analysis at the OTU level at a 10% FDR threshold found 87 OTUs with significantly higher relative abundance in cases vs controls and only five OTUs higher in controls (Supplementary Table 3). When we used the RDP classification algorithm to classify the consensus sequence for each of the 92 significantly different OTUs, bacteria with higher relative abundance in cases were mostly members of the phyla Firmicutes (42.6%), Bacteroidetes (25.5%) and Proteobacteria (24.5%) (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure 4). A rank-abundance curve demonstrates that the OTU differences between cases and controls (significant at 10% FDR) are entirely in low-abundance taxa (Supplementary Figure 5). This observation explains why there are differences between case and control in richness (Figure 1), which depends on the total number of taxa observed, but not evenness, which is more sensitive to changes in high-abundance taxa.

Maximum likelihood tree generated from the 371 OTUs in which the OTU was observed in at least 25% of our patients. The tree was generated using the RaxXML EPA server (http://i12k-exelixis3.informatik.tu-muenchen.de/raxml) (see Materials and methods). Branches are colored based on RDP Phylum level assignments. Red-colored branches represent OTUs significantly different between cases and controls within each Phylum (at 10% FDR).

To determine if the microbial differences seen between the cases and controls correlate with clinical metadata associated with the samples, we performed either regressions (for the continuous variable; Table 3a) or t-tests (for binary categorical variables; Table 3b) between each metadata category and the first principle component from our sequencing data PC1, generated by collapsing the 371 OTUs that are present in at least 25% of our samples (Figure 2). As shown in Tables 3a and b, PC1 does not show any significant correlation with any of the clinical categories at a 10% FDR except for the disease status (case–control) category, which would be significant even a FDR threshold of 1% (Table 3b). In addition, we performed correlations (for the continuous variables; Table 4a) and Wilcoxon/Kruskal–Wallis tests (for binary categorical variables; Table 4b) between the microbial richness of each sample and the metadata associated with that sample; the results from these tests show that there was no difference in richness with any of the metadata categories associated with our subjects apart from disease (case/control) status (Tables 4a and b).

Since obesity is a risk factor for development of CRC, and changes in the human microbiome have previously been associated with obesity (Turnbaugh et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009) we further evaluated the relationship between the relative abundance levels of the individual taxa and BMI and WHR. We classified subjects into one of the three BMI categories; normal (BMI <25), overweight (BMI=25–29) and obese (BMI ⩾30) and three WHR levels; low, medium and high based on accepted thresholds (http://www.bmi-calculator.net/waist-to-hip-ratio-calculator/waist-to-hip-ratio-chart.php). For each OTU, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was performed between the three groups for BMI and WHR. There were no OTUs that showed significant differences between the various BMI and WHR risk factor categories even if we were to set a FDR threshold as high as <200% (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Likewise, there were no significant differences in the diversity measures, richness and evenness, between the various risk factor categories (Figures 4 and 5). Finally, regressions between BMI values and WHR values against each taxa at the OTU level also showed no significant association between the OTUs with either BMI (Supplementary Figure 6) or WHR (Supplementary Figure 7) at an FDR threshold of <10% (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7).

Discussion

In a recent study, in which we used the more limited T-RFLP fingerprinting and traditional clone sequencing methods, we reported Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria as the predominant phyla in colonic mucosa (Shen et al., 2010). These findings are compatible with our current observations where we used a more advanced sequencing technology to gain better insights into the relationship between mucosal adherent bacteria and adenomas. The depth of sequencing and the larger sample size in this study provides better coverage and a better understanding of the overall structure and composition of the microbiota. For instance, the phylum Actinobacteria was not detected in our previous study (Shen et al., 2010) but was detected in this study. The current case–control study found a large number of differences within the microbial community between adenoma case and non-control subjects with higher microbial richness in cases than controls. In particular, we found increased relative abundance of potential pathogens such as Pseudomonas, Helicobacter and, Acinetobacter (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Table 3) and other genera belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria (Figure 2). The presence of these potential pathogens may directly increase the risk of adenoma development by changing the gut environment. For example, Helicobacter has a much higher relative abundance in cases vs controls (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3) consistent with previous studies, which implicate this bacterium in colorectal adenomas (Zumkeller et al., 2006; Burnett-Hartman et al., 2008; Takakura et al., 2008); a possible explanation for this association is that this microbe alters the pH of the gastrointestinal tract (Abbolito et al., 1992; Chen et al., 1997). Acidovorax spp., one of the bacterial signatures identified as significantly different between case and control in this study, is a flagellated, gram negative acid degrading member of the phylum Proteobacteria. Although, not much is known about its clinical epidemiology and pathogenicity in humans, it has been reported to also degrade nitro-aromatic compounds (Malkan et al., 2009). A potential mechanism for the Acidovorax–adenoma association could relate to the induction of local inflammation by increased flagellar proteins resulting from the higher abundance of Acidovorax (Tanaka et al., 2003; Takakura et al., 2008).

Another potential mechanism could be related to changes in the local gut environment that favors increased abundance of specific taxa. For example, acid producing bacteria such as Lactobacillus, are known to lower the gut pH and regulate the growth of other bacteria. It is possible that the increased abundance of Lactobacillus could influence levels of Acidovorax that have the ability to degrade acid produced by Lactobacillus as a carbon source. Interestingly, we observed that Lactobacillus was more abundant in cases than controls. Lactobacillus is considered a beneficial microbe (Gibson and Roberfroid, 1995; Duncan et al., 2004) with relatively low abundance in the gut (Eckburg et al., 2005). We propose that Lactobacillus spp. may induce changes in the adherent ecosystem that could alter the pH to create favorable conditions for bacterial dysbiosis. This is consistent with suggestions by Duncan et al. (2004) that bacteria that grow in acidic pH create an environment that can be exploited by more low pH-tolerant microbes. Cloacibacterium, another bacterium that differed significantly between case and control at the genus level, is a gram negative anaerobe. It is a Flavobacterium that belongs to the phylum Bacteroidetes and plays an important role in breaking down complex organic matter (Bernardet et al., 2002). Disruption of homeostasis in the adherent ecosystem may also account for the higher abundance of Cloacibacterium. Although we found that several bacterial genera were associated with colorectal adenomas and the exact mechanisms for bacterial dysbiosis–adenoma relationship are not well defined, we have attempted to suggest potential mechanisms and highlight a few genera. Other factors that change the colonic environment such as diet and host factors could also contribute to the bacterial dysbiosis and adenoma association. We recognize that there is limited information about the function of most of these bacteria as such our findings will need to be verified in a future studies. While these findings provide important clues to the relationship between microbial diversity and colorectal adenomas, the case–control design limits our ability to assess causality. However, our findings have the potential to inform future studies in animal models to evaluate mechanisms.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the presence of adenomas is associated with changes in the relative abundance of various taxa, including potential pathogens, present in the gut mucosa and that these changes are not significantly correlated with other clinical parameters such as obesity levels (WHR and BMI), age, NSIAD use and antibiotic use (Tables 3 and 4). Previous metagenomic studies have implicated the composition of the microbial community as contributing to obesity (Ley et al., 2005, 2006; Turnbaugh et al., 2006; Turnbaugh and Gordon, 2009; Turnbaugh et al., 2009) although this has been controversial (Larsen et al., 2010). In our study, we did not see any statistically significant relationship between BMI or WHR and any individual taxa within the microbial community (Figures 4 and 5; Supplementary Tables 4–7). Likewise, when we examined our data for a relationship between BMI and the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio, we observed no such correlation (data not shown). These results stand in contrast to previous studies that have observed that BMI is associated with the increased presence of Firmicutes (Turnbaugh et al., 2006; Turnbaugh and Gordon, 2009). It is unclear whether regional differences in subjects (all of our subjects were from North Carolina) or differences in sampling (stool sampling vs biopsies) can explain some of the differences between our work and previous results. We also cannot rule out the possibility that BMI or other factors might have achieved a statistically significant influence over the composition of the microbial community with a larger sample size than we had in our study. What seems inarguable from our data set, however, is that case–control status is asserting a larger degree of influence on the microbial community than any of the other clinical parameters that we collected (Tables 3 and 4). This observation suggests that conditions associated with adenoma formation are more strongly linked with the microbial community membership and structure, across patients, than any of the other factors that we evaluated. These observations are consistent with the idea that while healthy individuals have a great deal of inter-personal variation in their microbiome (Costello et al., 2009), disease states have a specific microbial signature.

Our observation that the microbial signature associated with adenomas is largely distinct from that associated with obesity suggests that next-generation sequencing of microbial communities may have considerable value in predicting the actual presence of adenomas. A strength of this study is the use of high-throughput 454 pyrosequencing for an in-depth evaluation of the adherent colonic mucosal bacteria in relation to adenomas. Two recent papers (Castellarin et al., 2012; Kostic et al., 2012), using similar high-throughput methods have independently found that Fusobacterium is associated with tissue from colorectal carcinomas. In addition, recent studies (Marchesi et al., 2011; Sobhani et al., 2011) compared the tissues of colonic tumors with non-malignant mucosa and found substantial differences in the associated microbiota. Together with our results, which describe differences in the microbiota from normal rectal mucosa of adenoma cases and controls, a picture is beginning to develop that link microbial changes to colorectal adenomas and cancer.

Accession codes

References

Abbolito MR, Ameglio F, Guerrera AM, Citarda F, Grassi A, Sciarretta F et al. (1992). The association of Helicobacter pylori infection with low levels of urea and pH in the gastric juices. Ital J Gastroenterol 24: 389–392.

Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A et al. (2004). The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 15718–15723.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y . (1995). A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B 57: 12.

Bernardet JF, Nakagawa Y, Holmes B . (2002). Proposed minimal standards for describing new taxa of the family Flavobacteriaceae and emended description of the family. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52: 1049–1070.

Bingham SA . (2000). Diet and colorectal cancer prevention. Biochem Soc Trans 28: 12–16.

Burcelin R, Luche E, Serino M, Amar J . (2009). The gut microbiota ecology: a new opportunity for the treatment of metabolic diseases? Front Biosci 14: 5107–5117.

Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Potter JD . (2008). Infectious agents and colorectal cancer: a review of Helicobacter pylori, Streptococcus bovis, JC virus, and human papillomavirus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 2970–2979.

Cani PD, Delzenne NM . (2009). Interplay between obesity and associated metabolic disorders: new insights into the gut microbiota. Curr Opin Pharmacol 9: 737–743.

Castellarin M, Warren RL, Freeman JD, Dreolini L, Krzywinski M, Strauss J et al. (2012). Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res 22: 299–306.

Chen G, Fournier RL, Varanasi S, Mahama-Relue PA . (1997). Helicobacter pylori survival in gastric mucosa by generation of a pH gradient. Biophys J 73: 1081–1088.

Chou HH, Holmes MH . (2001). DNA sequence quality trimming and vector removal. Bioinformatics 17: 1093–1104.

Costello EK, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Fierer N, Gordon JI, Knight R . (2009). Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 326: 1694–1697.

Duncan SH, Louis P, Flint HJ . (2004). Lactate-utilizing bacteria, isolated from human feces, that produce butyrate as a major fermentation product. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 5810–5817.

Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M et al. (2005). Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308: 1635–1638.

Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB . (1995). Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr 125: 1401–1412.

Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS et al. (2006). Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 312: 1355–1359.

Grice EA, Kong HH, Renaud G, Young AC, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW et al. (2008). A diversity profile of the human skin microbiota. Genome Res 18: 1043–1050.

Haas BJ, Gevers D, Earl AM, Feldgarden M, Ward DV, Giannoukos G et al. (2011). Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res 21: 494–504.

Hope ME, Hold GL, Kain R, El-Omar EM . (2005). Sporadic colorectal cancer--role of the commensal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Lett 244: 1–7.

Huycke MM, Gaskins HR . (2004). Commensal bacteria, redox stress, and colorectal cancer: mechanisms and models. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 229: 586–597.

Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E . (2010). Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin 60: 277–300.

Keku TO, Lund PK, Galanko J, Simmons JG, Woosley JT, Sandler RS . (2005). Insulin resistance, apoptosis, and colorectal adenoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 2076–2081.

Kostic AD, Gevers D, Pedamallu CS, Michaud M, Duke F, Earl AM et al. (2012). Genomic analysis identifies association of Fusobacterium with colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res 22: 292–298.

Kunin V, Engelbrektson A, Ochman H, Hugenholtz P . (2010). Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ Microbiol 12: 118–123.

Lance P . (1997). Recent developments in colorectal cancer. J R Coll Physicians Lond 31: 483–487.

Larsen N, Vogensen FK, van den Berg FW, Nielsen DS, Andreasen AS, Pedersen BK et al. (2010). Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS One 5: e9085.

Leek JT, Scharpf RB, Bravo HC, Simcha D, Langmead B, Johnson WE et al. (2010). Tackling the widespread and critical impact of batch effects in high-throughput data. Nat Rev Genet 11: 733–739.

Ley RE, Backhed F, Turnbaugh P, Lozupone CA, Knight RD, Gordon JI . (2005). Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11070–11075.

Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI . (2006). Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444: 1022–1023.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD . (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408.

Malkan AD, Strollo W, Scholand SJ, Dudrick SJ . (2009). Implanted-port-catheter-related sepsis caused by Acidovorax avenae and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol 47: 3358–3361.

Marchesi JR, Dutilh BE, Hall N, Peters WH, Roelofs R, Boleij A et al. (2011). Towards the human colorectal cancer microbiome. PLoS One 6: e20447.

Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA et al. (2005). Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437: 376–380.

Moore WE, Moore LH . (1995). Intestinal floras of populations that have a high risk of colon cancer. Appl Environ Microbiol 61: 3202–3207.

Petrosino JF, Highlander S, Luna RA, Gibbs RA, Versalovic J . (2009). Metagenomic pyrosequencing and microbial identification. Clin Chem 55: 856–866.

Powrie F, Uhlig H . (2004). Animal models of intestinal inflammation: clues to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Novartis Found Symp 263: 164–174 discussion 174-168, 211-168.

Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R . (2006). Role of the innate immune system and host-commensal mutualism. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 308: 1–18.

Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R . (2004). Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 118: 229–241.

Savage DC . (1977). Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annu Rev Microbiol 31: 107–133.

Scanlan PD, Shanahan F, Clune Y, Collins JK, O'Sullivan GC, O'Riordan M et al. (2008). Culture-independent analysis of the gut microbiota in colorectal cancer and polyposis. Environ Microbiol 10: 789–798.

Shen XJ, Rawls JF, Randall T, Burcal L, Mpande CN, Jenkins N et al. (2010). Molecular characterization of mucosal adherent bacteria and associations with colorectal adenomas. Gut Microbes 1: 138–147.

Sobhani I, Tap J, Roudot-Thoraval F, Roperch JP, Letulle S, Langella P et al. (2011). Microbial dysbiosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. PLoS One 6: e16393.

Takakura Y, Che FS, Ishida Y, Tsutsumi F, Kurotani K, Usami S et al. (2008). Expression of a bacterial flagellin gene triggers plant immune responses and confers disease resistance in transgenic rice plants. Mol Plant Pathol 9: 525–529.

Tanaka N, Che FS, Watanabe N, Fujiwara S, Takayama S, Isogai A . (2003). Flagellin from an incompatible strain of Acidovorax avenae mediates H2O2 generation accompanying hypersensitive cell death and expression of PAL, Cht-1, and PBZ1, but not of Lox in rice. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 16: 422–428.

Tsukumo DM, Carvalho BM, Carvalho-Filho MA, Saad MJ . (2009). Translational research into gut microbiota: new horizons in obesity treatment. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 53: 139–144.

Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI . (2009). The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol 587: 4153–4158.

Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE et al. (2009). A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457: 480–484.

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI . (2006). An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444: 1027–1031.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR . (2007). Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 5261–5267.

Willing B, Halfvarson J, Dicksved J, Rosenquist M, Jarnerot G, Engstrand L et al. (2009). Twin studies reveal specific imbalances in the mucosa-associated microbiota of patients with ileal Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 15: 653–660.

Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, Yu Y et al. (2009). Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 2365–2370.

Zumkeller N, Brenner H, Zwahlen M, Rothenbacher D . (2006). Helicobacter pylori infection and colorectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter 11: 75–80.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health NIH P30DK034987, R01 CA44684, P50 CA106991, R01 CA136887, K01 DK 073695. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers: All 454 pyrosequence data from this study have been submitted to Genbank database under the accession # SRS 166138.1-172960.2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanapareddy, N., Legge, R., Jovov, B. et al. Increased rectal microbial richness is associated with the presence of colorectal adenomas in humans. ISME J 6, 1858–1868 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.43

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.43

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Causal relationship between gut microbiota and cancers: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study

BMC Medicine (2023)

-

Exploring the characteristics of gut microbiome in patients of Southern Fujian with hypocitraturia urolithiasis and constructing clinical diagnostic models

International Urology and Nephrology (2023)

-

Epigenetics and the role of nutraceuticals in health and disease

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Reproducible and opposing gut microbiome signatures distinguish autoimmune diseases and cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Microbiome (2022)

-

Presence of Akkermansiaceae in gut microbiome and immunotherapy effectiveness in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer

AMB Express (2022)