Abstract

We assessed the microbial diversity and microenvironmental niche characteristics in the didemnid ascidian Lissoclinum patella using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, microsensor and imaging techniques. L. patella harbors three distinct microbial communities spatially separated by few millimeters of tunic tissue: (i) a biofilm on its upper surface exposed to high irradiance and O2 levels, (ii) a cloacal cavity dominated by the prochlorophyte Prochloron spp. characterized by strong depletion of visible light and a dynamic chemical microenvironment ranging from hyperoxia in light to anoxia in darkness and (iii) a biofilm covering the underside of the animal, where light is depleted of visible wavelengths and enriched in near-infrared radiation (NIR). Variable chlorophyll fluorescence imaging demonstrated photosynthetic activity, and hyperspectral imaging revealed a diversity of photopigments in all microhabitats. Amplicon sequencing revealed the dominance of cyanobacteria in all three layers. Sequences representing the chlorophyll d containing cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina and anoxygenic phototrophs were abundant on the underside of the ascidian in shallow waters but declined in deeper waters. This depth dependency was supported by a negative correlation between A. marina abundance and collection depth, explained by the increased attenuation of NIR as a function of water depth. The combination of microenvironmental analysis and fine-scale sampling techniques used in this investigation gives valuable first insights into the distribution, abundance and diversity of bacterial communities associated with tropical ascidians. In particular, we show that microenvironments and microbial diversity can vary significantly over scales of a few millimeters in such habitats; which is information easily lost by bulk sampling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine microbes are pivotal players in food webs, primary production and biogeochemical cycling (Samuel, 2000). The biodiversity of marine microbial communities has been under close investigation using culturing, ribotyping and, more recently, massive parallel pyrosequencing of the 16S rRNA gene or metagenomic surveys of bulk DNA extracted from the respective environments. Despite rapid accumulation of such sequence data, the extent of marine microbial biodiversity is still barely known (Pedrós-Alió, 2006), and uncultured bacteria composing the ‘rare biosphere’ are steadily accumulating (Sogin et al., 2006); although criticism concerning a technical overestimation of species diversity has been growing accordingly (Reeder and Knight, 2009; Kunin et al., 2010).

In recent years, the microbial diversity associated with sponges and other marine invertebrates has been under intense investigation, in part due to a prevalence of bioactive compounds in such organisms, with potential use in applied sciences (Taylor et al., 2007, 2011; Menezes et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2010; Webster and Taylor, 2011). In addition to marine sponges, didemnid ascidians present an interesting environment for the investigation of symbiotic relationships (Adams, 2002; Hirose and Maruyama, 2004) and the discovery of new bioactive compounds (Sings and Rinehart, 1996; Ogi et al., 2009; Erwin et al., 2010). The role and importance of ascidian-associated microbes versus the host as a source of such secondary metabolites remains largely unexplored. For example, Schmidt et al. (2005) reported the production of bioactive cyclic peptides, patellamides, in the symbiotic prochlorophytic cyanobacterium Prochloron spp., which is found in large quantities within the cloacal cavity of the didemnid ascidian Lissoclinum patella (Schmidt et al., 2005), whereas others have reported patellamide production in L. patella itself (Degnan et al., 1989; Sings and Rinehart, 1996; Salomon and Faulkner, 2002). Another unique cyanobacterium, Acaryochloris marina, grows in biofilms on the underside of didemnid ascidians, where it uses chlorophyll (Chl) d to sustain its photosynthesis using near-infrared radiation (NIR; Kühl et al., 2005). The A. marina type strain MBIC11017, originally isolated from L. patella, was hereafter sequenced and revealed a genome of unusually large size (Swingley et al., 2008). The relative abundance of A. marina in these epizoic microbial communities remains unknown and besides a recent genomic survey focusing on Prochloron, and its secondary metabolism (Donia et al., 2011), no further efforts have been made in studying the microbial diversity in L. patella.

Most surveys of microbial diversity are based on bulk sample analysis, with only few or missing metadata on the environmental characteristics of the sampled habitat. Thus, they lack key information about niche-defining physicochemical factors shaping the microbial assemblages. This is particularly critical when analyzing surface-associated microbial communities, where several studies of microbial mats (Ward et al., 2006; Kunin et al., 2008) and sediments (Lüdemann et al., 2000; Böer et al., 2009) have shown strong shifts in microbial communities along biogeochemical gradients over minute spatial scales. Although microenvironmental analysis of corals (Kühl et al., 1995), sponges (Hanna et al., 2005; Hoffmann et al., 2008) and ascidians (Kühl and Larkum, 2002; Kühl et al., 2005) have shown steep and dynamic microenvironmental conditions similar to biofilms and microbial mats, we are not aware of previous studies simultaneously mapping microbial diversity and fine-scale microenvironmental conditions in such organisms.

In this study, we employ a rare combination of molecular analysis, microscopic imaging and microsensor analysis to describe the microenvironments and microbial communities associated with L. patella. Microbial communities were sampled from three different microhabitats growing (i) on the high light-exposed surface of L. patella, (ii) inside the cloacal cavity of the ascidian and (iii) on the underside of L. patella. The microbial diversity was investigated by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. In addition to such molecular data, we present the very first description of the O2 and light microenvironment and the distribution of photopigments and photosynthetic activity across the investigated microhabitats associated with L. patella.

Materials and methods

More detailed information on Materials and methods are given in the Supplementary Online Materials.

Origin, preparation and transport of samples

Intact specimens (5–10 cm2) of 5–10 mm thick L. patella were sampled at low tide (∼2.8 m tidal range) from three different depths on the outer reef flat and crest off Heron Island (Figure 1; S23°26′055, E151°55′850): (i) 2.5–3.5 m (hereafter ‘deep’), (ii) 1.5–2.5 m (hereafter ‘intermediate’) and (iii) 30 cm (hereafter ‘shallow’). Specimens were kept in a shaded aquarium (<200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) with a continuous supply of fresh seawater (26–28 °C) before subsampling. Relatively flat and homogeneous pieces of L. patella with a surface area of ∼2 × 2 cm were cut with a scalpel and immediately rinsed and submerged in filtered seawater. Cross-sections were cut from homogenous pieces with a razor blade for subsequent imaging. For DNA analysis, three independent biological replicates were collected at the shallow and deep site, whereas two replicates were collected at intermediate depths. From each of these replicates, three microbial consortia were sampled: (i) the upper surface layer, (ii) the underside of L. patella, both of which were collected using a sterilized razorblade, and (iii) the middle section containing the cloacal cavity harboring the deep green Prochloron spp. symbiont, which was collected using a pipette and gentle squeezing. This sampling design resulted in a total of 24 samples, which were used in DNA analysis. Samples used for subsequent DNA extraction were immediately submerged in RNAlater (Ambion, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), incubated in a refrigerator overnight and then frozen at −80 °C the next morning. These samples were transported back to the laboratory on dry ice and stored at −80 °C upon arrival.

The tropical didemnid ascidian L. patella in its natural habitat. (a) Inner coral reef crest at low tide on Heron Island, QLD, Australia. (b) Specimen of L. patella found nested within dead and living coral branches. (c) Deep-green specimen of L. patella, where the green coloration originates from its obligate symbiont Prochloron spp. that resides in the cloacal cavities of the ascidian. (d) Cross-section of L. patella. Note the thick reddish biofilm covering the underside of the tunic and the green Prochloron cells in the cloacal cavity of the ascidian. ‘Surface’, ‘cloacal cavity’ and ‘underside’ denote the sites were samples were taken for subsequent analysis in this study.

Microsensor measurements

An intact specimen of L. patella was used for measuring the depth distribution of O2 and spectral scalar irradiance with optical and electrochemical microsensors. Scalar irradiance measurements were performed using a fiber-optic scalar irradiance microprobe mounted onto a motorized micromanipulator system (Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark) and connected to a spectrometer (QE65000, Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA; Kühl, 2005). The scalar microprobe was inserted in 0.2-mm steps into L. patella and the measured spectra were normalized to the spectral downwelling irradiance as determined from a black non-reflective beaker. Samples were irradiated vertically from above with a fiber-optic tungsten halogen lamp (KL-2500, Schott, Mainz, Germany). Oxygen microsensors (OX25 and OX50, Unisense) were connected to a multimeter and mounted onto the same micromanipulator system as described above. Data acquisition and sensor positioning during microprofiling of scalar irradiance or O2 concentration was performed using dedicated software (SensorTrace Pro, Unisense).

Hyperspectral imaging

The surface and underside of precut 2 × 2 cm pieces of ascidian tissue were imaged using a dissection microscope (SZ X16, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a hyperspectral image scan unit (100T-VNIR, Themis Vision, Bay Saint Louis, MS, USA). Hyperspectral image stacks were corrected (in Hypervisual 3.0, Themis Vision) to percent (%) reflectance using reflectance standards (Spectralon, Labsphere, North Sutton, NH, USA) and corrected for background noise under darkness. Normalized hyperspectral image stacks were processed according to Polerecky et al. (2009) and are presented in false color, quantifying the light attenuation around 710 nm (Chl d), 675 nm (Chl a; Figure 2c) and 560 nm (phycoerythrin; Figure 2d).

(a) Typical biofilm found on the underside of the tropical ascidian L. patella. (b) Cross-section of the same ascidian showing filamentous cyanobacteria (FCy) on the surface, part of the cloacal cavity containing green Prochloron cells (Pro) and the animal zooid. (c) Color-coded composite images of hyperspectral image stacks taken from the biofilm displayed in a, red quantifies the absorption at 710 nm (specific for Chl d), whereas green quantifies absorption at 675 nm (specific for Chl a). (d) Hyperspectral composite images color coded to quantify absorption at 560 nm (specific for phycoerythrin); images were taken from the same biofilm as displayed in b. The numbers in both c and d denote specific areas of interest, exhibiting the reflectance spectra shown in e and f.

Variable chlorophyll fluorescence imaging

The photosynthetic activity of biofilms on the underside and the surface of the tunic of L. patella, respectively, were monitored by variable chlorophyll fluorescence imaging using a pulse-amplitude-modulated imaging system (I-PAM, Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) using blue light-emitting diodes (470 nm) for measuring and actinic light. Blue measuring light is efficient in monitoring the photosynthetic activity of the NIR-absorbing A. marina, due to the Chl d Soret band absorption at 460–470 nm. Pulse-amplitude-modulated chlorophyll fluorescence imaging systems have been described in detail elsewhere (Schreiber, 2004; Kühl and Polerecky, 2008; Trampe et al., 2011).

Molecular analysis

DNA extraction

Biofilms from the underside and the surface, stored in RNAlater (Ambion, Applied Biosystems), were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and then crushed in precleaned and sterilized mortars. The resulting powder was immediately processed using the standard FastDNA for soil kit (Qbiogene, Illkirch, France), with two additional bead-beating cycles. Samples from the cloacal cavity of L. patella were directly used in the bead-beating process but otherwise treated the same way as the other two samples. Between bead-beating cycles, the samples were cooled on ice for 2 min. The resulting DNA was eluted in TAE buffer and the DNA was quantified using a Qubit-fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), checked for integrity on a 0.8% agarose gel and stored at −20 °C until further use.

PCR amplification and pyrosequencing

Tag-encoded 16S rRNA gene (=amplicon) pyrosequencing was performed on DNA extracted from a total of 24 samples, encompassing the three biofilms (surface, cloacal cavity and underside) sampled at the shallow and deep sites (three replicates each) or at intermediate depths (two replicates each). The DNA concentration in all samples was adjusted to 5 ng/μl using molecular biology grade water. A 466-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers 341F (5-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3) and 806R (5-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3) flanking the V3 and V4 regions (Youngseob et al., 2005). PCR amplification was performed using the Phusion Hot Start DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes Oy, Espoo, Finland) with the following cycle conditions: 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 35 cycles of 98 °C for 5 s, 56 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s and a final extension of 72 °C for 5 min. After PCR amplification, the samples were held at 70 °C for 3 min and were then moved on ice, preventing hybridization between PCR products and nonspecific amplicons. PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and purified using the Montage Gel extraction kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). A second round of PCR was performed as described above, except that this time primers with adapters and tags were used (Holmsgaard et al., 2011) and the number of cycles was reduced to 15. After further gel purification and quantification using a Qubit-fluorometer (Invitrogen) the amplified fragments were mixed in equal concentrations and sequenced on one of two regions of a 70–75 GS PicoTiterPlate using a GS-FLX pyrosequencing system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland).

Sequence analysis and visualization

A total of 182.375 amplicon sequence reads were obtained from pyrosequencing. After quality filtering, 161.499 sequences were left for further sequence analysis using the QIIME software package (QIIME, version 1.2.1, http://qiime.sourceforge.net/). Phylotyping was performed by picking representatives from each operational taxonomic unit (OTU) and aligning them against a V3/V4-truncated core alignment of the Greengenes database (http://greengenes.lbl.gov). All OTUs identified as chloroplasts were subsequently removed from the OTU table, reducing the total number of sequences in the data set to 140.871. In order to present a succinct overview of the major taxonomic groups OTUs summing to >100 sequences across all samples were used for further log10+1 transformation and visualization in a heatmap using the taxonomy assignments described. The same subset of OTUs was used for metabolic assignments, based on a thorough literature search of conserved key properties within major taxonomic groups.

Results

Overall distribution of biofilms and pigmented cells

Distinct pigmented bacterial biofilms covered the underside and the surface of the tropical didemnid ascidian L. patella, while large amounts of green symbiotic Prochloron cells were contained within the cloacal cavity of the animal (Figures 1d and 2).

Photopigment distribution

Ascidians collected at intermediate depths were imaged using light and fluorescence microscopy and depicted green-yellowish biofilms on the underside (Figure 2a) and clusters of red filamentous cyanobacteria in the opening of the cloacal cavity of the animal surrounded by a thin biofilm on the surrounding upper surface of the L. patella tunic (Figure 2b). Prochloron cells were abundant in the cloacal cavity of all collected specimens of L. patella forming a deep-green layer (Figures 1d and 2b). Hyperspectral imaging revealed photopigments absorbing light in the NIR, typical for Chl d on the underside of L. patella (Figure 2c; absorptivity at 710 nm displayed in red) mixed with photopigments with absorption characteristics typical for Chl a (Figure 2c; absorptivity at 675 nm displayed in green). Surface-associated filamentous bacteria on the upper surface of L. patella showed absorbance distinctive for phycoerythrin (Figure 2d; absorptivity at 560 nm displayed in red) as well as Chl a (Figure 2f). Reflectance spectra of distinct areas of interest on the underside (Figure 2e) and the surface (Figure 2f) biofilms showed reflectance minima around 710 nm (Chl d specific) and 675 nm (Chl a), respectively.

Light and O2 microenvironments in L. patella

A scalar irradiance probe was inserted into an intact specimen of L. patella to capture qualitative and quantitative changes in light distribution throughout the three microhabitats. Measurements just below the surface of L. patella indicated a local increase in scalar irradiance up to 216% due to intense scattering in the upper tunic (red line; Figure 3c). Light in the cloacal cavity of L. patella (green line; Figure 3c) was reduced by an order of magnitude in the blue and red part of the spectrum when compared with subsurface measurements. Absorption signatures of chlorophylls (Chl a 440/675 nm and Chl b ∼453/642 nm), bacteriochlorophyll (Bchl a 805/830–890 nm) and phycobiliproteins (phycoerythrin ∼560 nm and phycocyanin ∼620–630 nm) were present in both the cloacal cavity containing Prochloron cells as well as in the biofilm covering the underside of the ascidian. Light reaching the underside of the ascidian (blue line; Figure 3c) was enriched in NIR (>700 nm), whereas visible wavelengths were further depleted in intensity to ∼0.1–1% of the incident irradiance.

Microenvironments and photosynthetic activity in L. patella and its associated biofilm communities. (a) Cross-section of L. patella. Colored dots indicate the different layers of the animal, where measurements where performed. Red denotes measurements taken just below the surface, green just below the cloacal cavity, and blue just below the underside of the ascidian. (b) Oxygen concentration gradients measured through an intact specimen of L. patella in darkness or under an irradiance of 1350 μmol photons m−2 s−1. The upper surface of the tunic and the boundary toward the cloacal cavity are indicated by the two horizontal lines. (c) Spectral scalar irradiance (in percent (%) of incident irradiance at the tunic surface) as measured with a fiber-optic microprobe just below the three different compartments within L. patella. Color coding is the same as in a. (d) Photosynthetic activity measured as the photosystem II-related rETR versus irradiance in the three different biofilms.

We captured the temporal and spatial O2 distribution in L. patella by performing stepwise O2 measurements under light and in darkness. During darkness, anoxic conditions prevailed below a depth of ∼0.8–1 mm, whereas the surface layer of the tunic remained well oxygenated under dark conditions. During light conditions, we observed a strong O2 uptake in the upper tunic, whereas O2 concentrations increased stepwise to a maximum of ∼250% air saturation within the cloacal cavity of L. patella under an incident irradiance of 1350 μmol photons m−2 s−1 at its surface. Experimental light–dark shifts with the O2 microsensor tip positioned in the cloacal cavity of L. patella showed a rapid O2 depletion immediately after onset of darkness (data not shown). No O2 measurements were performed in deeper layers due to risk of breaking the fragile glass microelectrode.

Photosynthetic activity of phototrophic biofilms

Photosynthetic activity was measured as the relative electron transport rate (rETR) versus quantum irradiance for all three biofilm communities associated with L. patella (Figure 3d). At an irradiance of ∼1000 μmol photons m−2 s−1, the highest photosynthetic activity was found in the Prochloron-rich middle section of L. patella (rETR >19); under the same irradiance the biofilm on the underside of L. patella exhibited a rETR of ∼6. The rETR versus quantum irradiance curve of surface-associated filamentous bacteria increased steeply, reaching a rETR of ∼13 and then dropped to 0 at photon concentrations in excess of 324 μmol m−2 s−1. Phototrophic bacteria on the underside reached light saturation at ∼400 μmol photons m−2 s−1, whereas cells in the cloacal cavity of L. patella were not saturated at the maximum irradiance employed in our PAM measurements (1000 μmol photons m2 s−1).

Microbial diversity of biofilms associated with L. patella

The microbial diversity of 24 individual samples was evaluated using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. All three biofilm communities were sampled along a gradient ranging from the outer slope of the reef crest (depth ∼2.5–3.5 m), the reef crest itself (depth ∼1.5–2.5 m) to the inner reef flat (depth 0.3–1 m). The top 10 dominating OTUs and their taxonomic assignments on the phylum level are shown in Table 1. All samples across depth gradients and throughout the three different biofilm communities were dominated by sequences related to the phyla Cyanobacteria and Proteobacteria. Sequences from the tunic surface were mostly associated with Cyanobacteria, which were most common in the deep site (80%) and became lower in numbers with decreasing depth, reaching >60% at the intermediate site and ∼20% at the shallow site (see also Supplementary Figure S1). Proteobacteria-associated sequences on the surface biofilm followed the opposite trend and increased with decreasing depth. Other abundant sequences from the surface samples were related to Bacteroidetes, Verrucomicrobia and Fusobacteria.

Sequence reads retrieved from the cloacal cavity of L. patella were mostly assigned to the phylum Cyanobacteria (about 68–90% for the three depths), whereas the second most abundant phylum was Proteobacteria (7–25%). Less abundant phyla in the cloacal cavity included Bacteroidetes, Fusobacteria and the candidate phylum OP8. Cyanobacterial sequences were also abundant on the underside of the ascidian and their contribution remained relatively constant across depths (45–58%); the same was true for sequences related to Proteobacteria (20–27%) and Bacteroidetes (12–20%). In addition to these three phyla, the biofilms on the underside contained sequences associated with Verrucomicrobia, Chloroflexi and Actinobacteria.

Clustering of the most abundant bacterial OTUs in a heatmap

In order to display clustering of OTUs in a succinct way, only OTUs containing a total of >100 sequences across all samples were log10+1 transformed and subsequently clustered in a heatmap (Figure 4). Visually, the microbial diversity presented in Table 1 is reflected in the heatmap. Samples taken from the underside showed a high diversity, as reflected in the amount of OTUs and their relative abundance, while a lower diversity was found in biofilms originating from the surface and the cloacal cavity. Euclidean distance analysis revealed four distinct clusters, which were color coded and labeled numerically. Cluster I (light blue) contains samples taken at all three depths originating from the underside of L. patella. Cluster II (green) encompasses only samples taken from the cloacal cavity (=Prochloron) from all three depths. Cluster III (yellow) is nested within cluster II and contains three surface samples, which were all sampled at shallow depths and are dominated by OTUs taxonomically assigned to Flammeovirgaceae and Kiloniella spp., both of which are less pronounced in other surface samples taken at deeper depths. Cluster IV (red) contains the remaining surface samples from the intermediate and deep site and a single sample from the cloacal cavity (intermediate depth). Within these clusters, the most frequent OTUs belong to: cluster (I) Azospirillum brasilense, A. marina, Symploca spp. and the family Flammeovirgaceae; cluster (II) Prochloron, Kiloniella spp., Rhodospirillaceae, Vibrio spp. and HMMVPog-54; cluster (III) Kiloniella, Flammeovirgaceae and Planktothricoides; and cluster (IV) Planktothricoides spp., Kiloniella and Flammeovirgaceae.

Heatmap of 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained from bacterial biofilms associated with the underside, the surface or the cloacal cavity (=Prochloron) of L. patella, respectively. Independent biological replicates of the sampled biofilms are labeled sequentially, that is, ‘Surface.deep.A–C’ indicating three replicates. The three sampling depths are indicated after the name of the biofilm and denote the ‘deep’ (2.5–3.5 m), ‘intermediate’ (1.5–2.5 m) and ‘shallow’ site (0.3–1 m). Only OTUs with a sum of >100 assigned sequences across all samples were used for further log10+1 transformation. Taxonomy was assigned to OTU representatives using best Blast hits against the Greengenes database. Duplicate OTUs were numbered sequentially for clarification. OTU clustering is shown along the y axis; dendrogram distances are based upon relative abundances within the data matrix and not on phylogenetic relationships. The top dendrogram is based on Euclidean distances and represents clustering into four distinct clusters (1–4) according to relative abundances within the data matrix. Cluster I (light blue) contains all samples originating from the underside of the ascidian, and cluster II (green) contains all samples taken from the cloacal cavity (=Prochloron), except one. Cluster III (yellow) is nested within cluster II and contains three surface samples. Cluster IV (red) contains the remaining surface samples and the last sample taken from the cloacal cavity.

Estimation of microbial richness and diversity

The complexity and richness of communities can be simplified and expressed by nonparametric estimators, providing a way to compare complex communities with each other and estimate the completeness of sampling (Schloss and Handelsman, 2005). Species richness is frequently measured as the number of OTUs present in a sample and is in this study given as the chao1 and abundance based-coverage estimator. Species diversity takes into account the evenness of the OTU distribution and is commonly expressed in the form of the Shannon index (H). Read libraries were rarefied to accommodate for the lowest number of reads found in our data set (=4009, see Supplementary Table 1) and used for subsequent calculation of microbial richness and diversity estimators. The highest bacterial diversity was found in samples originating from the underside (H index=6.58–7.22, see Table 2), whereas the lowest bacterial diversity occurred in samples taken from the cloacal cavity of L. patella (H index=1.07–3.30). Diversity estimated by the Simpson index showed a similar pattern, with indices ranging from 0.19 (cloacal cavity) to 0.98 (underside). Richness estimates ranged from 167 to 1278 (chao1) and 176 to 1268 (abundance based-coverage estimator), with the lowest values found in the cloacal cavity of L. patella dominated by Prochloron, whereas the greatest richness was found in samples taken from the underside of L. patella.

Oxygen and carbon metabolism of L. patella-associated microbes

Taxonomic assignments displayed in the heatmap were used to determine the O2 and carbon metabolism in the major bacterial OTUs; this was done by a thorough literature research identifying the key conserved properties for the dominating OTUs. This approach has some uncertainties but still provides a general overview of the metabolic functions in the associated biofilms. Phototrophic bacteria were generally abundant in the cloacal cavity, on the underside and the surface of L. patella (Supplementary Figure S2A). Sequences associated with chemotrophic bacteria seem to dominate the microbial community on the underside of L. patella at intermediate depths and surface biofilms at shallow depths. Sequences belonging to aerobic bacteria were commonly found in all three microenvironments (Supplementary Figure S2B), whereas facultative and obligate anaerobes were more often found in the cloacal cavity than on the surface or underside of the ascidian.

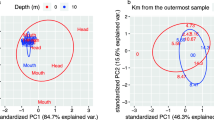

Principal component analysis of associated biofilm communities

Principal component analysis of the jackknifed-weighted UniFrac distances revealed two distinct clusters of characteristic communities found (i) on the underside and (ii) in the cloacal cavity of L. patella (Figure 5). Samples originating from the cloacal cavity clustered to the right of the primary axis (42.23% of the variation explained), whereas samples taken from the underside were found clustered to the left of the primary axis. Both samples taken from the underside and the cloacal cavity also cluster in the second dimension (25.43% of the variation explained). Samples taken from the surface formed a less stringent cluster and appeared somewhat related to bacterial communities found in the cloacal cavity. Three of the surface-associated samples are located in the lower left of the graph, forming their own separate cluster. In combination, the two principal component analysis axes explained 67.6% of the variation between the different microbial communities on and within L. patella.

Sequence abundance of phototrophic bacteria as a function of depth

Sequences assigned to bacterial groups known to contain photopigments (Bchl a and Chl d) absorbing near infrared radiation were used to determine a potential depth dependency in relative sequence abundance. Linear regression revealed a strong negative correlation between depth and the relative abundance of sequences belonging to the family Rhodospirillaceae (R2=0.882, Figure 6a), Rhodobacteraceae (R2=0.757, Figure 6c) and the cyanobacterium A. marina (R2=0.842, Figure 6b). Rhodospirillaceae-associated sequences found on the surface of L. patella were much more abundant at shallow depths (11.6±2.3%) than in intermediate (0.13±0.14%) and deep waters (0.18±0.14%). The same depth gradient was observed on the underside of L. patella for the Chl d-containing cyanobacterium A. marina (shallow=14±0.9%, intermediate=6.78±6.3% and deep=1.3±0.5%) and the purple bacteria Rhodobacteraceae within the cloacal cavity of the ascidian (shallow=1.9±0.86%, intermediate=0.59±0.05% and deep=0.25±0.13%). A less supported correlation (R2=0.234, Figure 6d) was obtained for the bacteriochlorophyll containing genus Chloracidobacteria found on the underside of the ascidian. The relative abundance of Chloracidobacteria-associated sequences was generally low but larger in deeper waters (0.47±0.38%) than in intermediate (0.43±0.34%) and shallow waters (0.19±0.08%).

Percent of phototrophic bacteria-related OTUs versus sampling depth. The sum of several OTUs taxonomically assigned to either (a) Rhodospirillaceae, (b) A. marina, (c) Rhodobacteraceae or (d) Chloracidobacteria were calculated for each sampling site and depth. Two (intermediate depth) or three (shallow and deep site) biological replicates are displayed in the graph as individual points. The relative percentage of sequences was calculated for the biofilm sample and correlated with the depth at which samples were taken. Correlation coefficients were determined by linear regression.

Discussion

Three distinct microhabitats were found associated with L. patella, separated by only few millimeters of animal tissue and characterized by steep gradients of the key physicochemical parameters light and O2. All three microhabitats harbored distinct microbial communities dominated by Cyanobacteria. Furthermore, we could correlate the distribution of particular types of microbes to the light and O2 microenvironment—such correlation is often not done or even impossible in many surveys of microbial diversity because of bulk analysis and/or lack of appropriate metadata. In the following, we discuss these findings in more detail.

Thick tufts of filamentous cyanobacteria containing Chl a and phycoerythrin were commonly found lining the opening of the cloacal cavity of L. patella, whereas the biofilm community on the underside was heterogeneously distributed and dispersed as distinct clusters often containing Chl a and d and phycobiliproteins. Functional Chl d has thus far only been found in A. marina, where it enables the use of NIR for oxygenic photosynthesis. Other ascidian species have previously been shown to host Chl d-containing phototrophs (Kühl et al., 2005; López-Legentil et al., 2011; Martínez-García et al., 2011), and even a global distribution of Chl d-containing bacteria has been suggested (Kashiyama et al., 2008; Behrendt et al., 2011). Our spectral irradiance measurements demonstrate that NIR is enriched in the cloacal cavity and the underside of L. patella as compared with visible light, supporting the occurrence of Chl d-containing phototrophs in this optically defined microniche. Similar patterns of NIR enrichment have been observed in coral skeleton (Magnusson et al., 2007) and the underside of other didemnid ascidians, that is, Diplosoma virens and Trididemnum paracyclops (Kühl et al., 2005; Larkum and Kühl, 2005).

In marine environments, seawater readily attenuates NIR and this attenuation is correlated with water depth and temperature (Pegau and Zaneveld, 1993; Pegau et al., 1997). Interestingly, A. marina constitutes one of the largest clusters of OTUs identified from the underside of L. patella and we observed a strong negative correlation between A. marina-related sequences and sampling depth, suggesting that NIR attenuation through the water column is an important determining factor for the abundance of A. marina. This hypothesis is further corroborated by negative correlations of water depth and sequence abundance in the two proteobacterial families Rhodobacteraceae and Rhodospirillaceae, which contain phototrophs capable of producing Bchl a (Ferguson et al., 1987; Imhoff and Hiraishi, 2005). Bchl a absorbs further into the infrared part of the spectrum (>800 nm), thus making Rhodobacteraceae and Rhodospirillaceae even more susceptible to attenuation by seawater. Martinez-Garcia et al. (2011) sampled the Mediterranean ascidian Cystodytes dellechiajei in shallow waters (<10–23 m) and did not recover sequences related to A. marina using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. On the contrary, the same study found Chl d-like photopigments using fluorescence microscopy on the same ascidians, stressing the possibility for other bacteria as carriers of Chl d; how these bacteria then would survive under relatively low NIR concentrations remains unknown. As a side note, it was encouraging to find comparable abundance estimates of Chl d-containing phototrophs using both amplicon sequencing in comparison with pigment abundance data from hyperspectral imaging (data not shown, for methodology see Supplementary Online Material).

Additional measurements of scalar irradiance in the cloacal cavity of L. patella revealed spectral absorption signatures specific for the photopigments Chl a, phycobiliproteins and Bchl a, and a strong attenuation of visible light in both the Prochloron-containing cloacal cavity and the lowermost tunic-associated biofilm. Ascidian-associated photopigments have been investigated before and essentially all major chlorophylls (Chl a, b, c and d) were found present on the surface of the Mediterranean ascidian C. dellechiajei (Martínez-García et al., 2011). Recently, a new symbiotic Acaryochloris species, Candidatus Acaryochloris bahamiensis nov. sp., was found within the tunic of the didemnid ascidian Lissoclinum fragile, even demonstrating compartmentalized distribution of Chl d and phycobiliproteins within single A. marina cells (López-Legentil et al., 2011).

The strong light-scattering effects measured on the surface of L. patella with scalar irradiance reaching up to 216% of the incident irradiance is possibly due to reflection by the white spicule-filled tunic commonly produced by didemnid ascidians in combination with light trapping due to a higher refractive index in the tunic as compared with the overlaying water (Kühl and Jørgensen, 1994). Light intensities of up to 280% of incident light have been reported on the surface of microbenthic communities (Kühl and Jørgensen, 1994; Kühl et al., 1994) as well as different types of corals (Kühl and Jørgensen, 1994; Magnusson et al., 2007). The high-light environment found on the surface of L. patella presumably selects for phototrophs with appropriate protective mechanisms enabling them to photosynthesize under these conditions.

Oxygen microsensor measurements revealed distinct O2 microenvironments on and within L. patella. Oxygen concentrations within the cloacal cavity fluctuated from anoxia during darkness to supersaturating conditions during light, whereas the surface biofilm and uppermost tunic remained well oxygenated throughout light and darkness. Oxygen consumption was observed just below the surface of L. patella. This O2 uptake could be due to the animal itself or a bacterial community not recovered by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, as the inner part of the tunic was not sampled. We observed a rapid decline in O2 concentration in the cloacal cavity of L. patella upon experimental light–dark shifts. Hence, we can hypothesize that the light and O2 gradients will fluctuate strongly with solar irradiance over the diel cycle. This would present a dynamic microenvironment selecting for specific adaptations in the associated microbial communities (Ley et al., 2006), which may be reflected in the functional groups of associated bacteria and their microbial diversity.

The diversity of bacteria across L. patella followed a steep spatial gradient, where three distinct microbial communities were separated by only few millimeters of the ascidian tunic. The microbial community on the underside was highly diverse, with an average Shannon index (H) of 6.9±0.2, more variable on the well oxygenated surface (3.3±1.7) and generally much lower within the cloacal cavity of L. patella (1.8±0.7). In comparison, marine planktonic habitats exhibited H indices ranging from 4.4 to 5.4 (Schloss et al., 2009), whereas temperate coastal microbial mats were found to be slightly more diverse (H: 5.9±0.4; Bolhuis and Stal, 2011). Menezes et al. (2010) did not calculate H indices but still found the bacterial community associated with the didemnid ascidian D. ligulum (which is not known to contain Prochloron) to be the most diverse of all eight invertebrate species sampled.

Assigning metabolic functions based on 16S rRNA gene sequences involves some uncertainties but can still provide valuable information on the major metabolisms in microbial communities (Barott et al., 2011; Bolhuis and Stal, 2011). Functionally, the three microhabitats found on L. patella were apparently dominated by aerobic bacteria, yet facultative anaerobes were present, most prominently in the cloacal cavity of L. patella, where the microenvironment was found to be the most variable in terms of O2 concentrations, showing rapid shifts between anoxia in darkness and hyperoxia under high irradiance. Sequences associated with obligate anaerobes (genus Propiogenium) were found in the well-oxygenated middle section of L. patella as well as on the outer surface. Members of the genus Propiogenium are known commensals of higher animals capable of growing on succinate, an important end product in anaerobic metabolic processes (Schink and Pfennig, 1982). If Propiogenium is truly a genus of only obligate anaerobes, they must exist in permanent anoxic microenvironments within L. patella, which even our fine-scale analysis using microsensors was not able to retrieve or, alternatively, such bacteria are able to survive oxic conditions during the day until anoxia at nighttime.

The diversity of microbes and their putative metabolism has been studied in the coral holobiont and associated algae (Barott et al., 2011) and in microbial mats (Bolhuis and Stal, 2011) by use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing. In comparison with our investigation of L. patella, coral-associated algae hosted a similar number of aerobic bacteria (53–94%) but fewer phototrophs (5–32%), whereas corals had almost no phototrophic bacteria associated with them (<1%) and hosted fewer aerobes (Barott et al., 2011). Temperate microbial mats were found to harbor ∼30% photoautotrophs consisting of Cyanobacteria and photoheterotrophic Rhodobacterales, but were otherwise dominated by chemoorganotrophs (Bolhuis and Stal, 2011). Despite the close physical connection of corals and ascidians on coral reefs, their biofilm communities are functionally different and probably the result of adaptation to specific microenvironments or active involvement of the host in shaping the microbial assemblage. However, as the functional assignments in our study are solely based upon conservation of key properties within major taxonomic groups, we are certainly underestimating the real diversity of functional groups that remain hidden in our sequence data.

In terms of sequence abundance, the phyla Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes were dominating all three microbial communities in L. patella, but their relative abundance varied according to sample depth and location. The cloacal cavity of L. patella was predominated by sequences belonging to OTUs classified as Prochloron spp., a symbiont well known to associate with didemnid ascidians (Lewin, 1981; Lewin and Cheng, 1985). Prochloron was first discovered in the early 1970s and received much attention because of its pigment composition (Chl a and b, absence of phycobiliproteins), which suggested its involvement in chloroplast evolution (Whatley and Whatley, 1981). In 2005, a new class of cytotoxic compounds, patellamides, was found encoded in the Prochloron genome (Schmidt et al., 2005), and recently a wide ecological distribution of these gene cassettes was described (Donia et al., 2011). The ecological and functional roles of these compounds remain enigmatic but involvement in metal-detoxification or metal-concentration mechanisms has been suggested (Bertram and Pattenden, 2007). Interestingly, other compounds within the same chemical family, that is, cyanobactins, are toxic to other cyanobacteria, possibly providing Prochloron and other cyanobacteria synthesizing such compounds with competitive advantages over other cyanobacteria (Todorova et al., 1995; Jüttner et al., 2001; Hirose et al., 2009). Such allelopathic interactions may explain our finding of only a few other cyanobacteria within the cloacal cavity of L. patella.

The cloacal cavity of L. patella exhibited dynamic changes in O2 conditions, with rapid O2 depletion to anoxia in darkness, potentially conducive to anaerobic processes and bacterial growth. A recent Prochloron genome-sequencing effort revealed that the bacterium is heavily involved in nitrogen metabolism, but not in N2 fixation (Hirose et al., 2009), contrasting previous reports (Paerl, 1984; Kline and Lewin, 1999). We found sequences closely related to the plant rhizosphere bacterium Azospirillum brasilense to be a significant part of the microbial community within the cloacal cavity and on the underside of L. patella. A. brasilense has long been recognized for its capability in terrestrial N2 fixation (Michiels et al., 1989). Performing N2-fixation assays on Prochloron spp. in the presence of A. brasilense or other diazotrophs could thus have caused false-positive results. As a side note, numerous studies have tried to enhance crop production in saline soils using inoculations of A. brasilense isolated from high-salinity environments (Nabti et al., 2007, 2010). Our finding of A. brasilense-like bacteria in high-salinity seawater could accelerate the search for a halo-tolerant rhizosphere candidate.

Phyla dominating the surface of L. patella appear to be following a depth-dependent relationship: Shallow waters apparently promoted the occurrence of Proteobacteria, whereas Cyanobacteria are dominantly found in deeper waters. Principal component analysis revealed a tight clustering of three surface samples, all originating from shallow water, highlighting the presence of depth-specific bacterial communities. On the surface of L. patella, a large proportion of sequences clustered into two large OTUs taxonomically classified as Planktothricoides and Rhodospirillaceae. The genus Planktothricoides contains freshwater cyanobacteria known for their bloom formation and potential toxicity (Suda et al., 2002). Planktothricoides has consistently been detected on a Mediterranean ascidian throughout different macroecological conditions and geographic areas (Martínez-García et al., 2011). To our knowledge, only ascidians have been found to harbor Planktothricoides in marine environments, suggesting specificity of these surface-associated bacteria on a global scale. Rhodospirillaceae (that is, purple non-sulfur bacteria) are known for their capability to perform anoxygenic photosynthesis, owing their distinct color to bacteriochlorophylls and carotenoids (Ferguson et al., 1987). Sequences resembling Rhodospirillaceae were predominantly retrieved from ascidians collected in shallow waters, emphasizing their preference for environments with sufficient near infrared-radiation.

Previous studies on ascidian-associated bacterial communities are exemplifying their diversity and geographic specificity. Cyanobacteria were found to be common among epibiotic phototrophs covering the Mediterranean ascidian C. dellechiajei (Martínez-García et al., 2011) and within the tunic of Caribbean didemnid ascidians (López-Legentil et al., 2011) but were completely absent in three species of ascidians sampled on the eastern US coast (Tait et al., 2007) and two ascidian species from the north coast of Brazil (Menezes et al., 2010). Bacteria sampled from the tunic tissue and the surfaces of various ascidians revealed sequences belonging to Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes (Martínez-García et al., 2009; Menezes et al., 2010), as well as Alphaproteobacteria (Tait et al., 2007), thus closely resembling some of the recovered phyla from L. patella.

The bacterial diversity associated with ascidians represents a valuable reservoir in the search for bioactive compounds as well as novel photopigments, and exhibits a large potential in the ongoing search for extremophile bacteria and their use in applied sciences. A thorough description of the bio-diversity and microenvironments associated with ascidians may facilitate more efficient cultivation and isolation of novel bacteria from such microhabitats. Combined studies, incorporating analysis of gene expression and microenvironmental measurements, have been performed in microbial mats in hot springs (Steunou et al., 2006, 2008; Jensen et al., 2011), but are otherwise scarce, in particular with respect to large-scale analysis of expression using transcriptome analysis. Relating functional regulation and transcript abundance in a defined and well-described system, such as L. patella, could help to elucidate microscale variations of in situ microbial metabolism and interactions across microhabitats, further revealing competitive and adaptive mechanisms shaping the microbiome of didemnid ascidians. Our first description of the distinct microhabitats and microbial communities associated with L. patella through molecular analysis, imaging and microenvironmental analysis is giving new insights into ascidian-associated bacterial communities and phototrophs in particular, and will help aiding future studies to relate changing microenvironments to functionally relevant adjustments in bacterial communities.

Conclusion

Only a few millimeters of ascidian animal tissue separate three very different microhabitats in L. patella, characterized by steep gradients of O2, light intensity and spectral quality that change dynamically upon changing solar irradiance. In general, all microbial communities associated with these microhabitats in L. patella were dominated by cyanobacteria and aerobic bacteria, albeit facultative anaerobes were present, suggesting specific adaptations to the highly variable O2 conditions in L. patella over the diel cycle. Microbial diversity was lowest in the cloacal cavity and highest in biofilms sampled from the underside of the ascidian, reflecting community-wide adaptations to the physicochemical microenvironments associated with L. patella. The biofilm communities harbored conspicuous bacteria including diazotrophs such as A. brasilense, inhabiting both the cloacal cavity and the underside of L. patella, and the unique Chl d-containing cyanobacterium A. marina. Sampling of L. patella along a depth gradient across the coral reef crest revealed a negative correlation between the abundance of phototrophic bacteria employing NIR (Rhodospirillaceae, Rhodobacteraceae, Chloracidobacteria and A. marina) and water depth, indicating that their abundance was strongly influenced by the availability of NIR, which is absorbed by seawater. This first detailed description of the microbial diversity and microhabitats associated with L. patella highlights the need to perform such studies at ecologically relevant spatial scales. Both microenvironmental niche-defining parameters and microbial communities can vary significantly over small distances in surface-associated microbial communities, and important knowledge about the structure and function of such communities may be lost in microbial biodiversity surveys of bulk samples with limited metadata.

References

Adams D . (2002). Symbiotic interactions. In: Whitton B, Potts M (eds). The Ecology of Cyanobacteria, 1st edn. Springer: Netherlands, pp 523–561.

Barott KL, Rodriguez-Brito B, Janouškovec J, Marhaver KL, Smith JE, Keeling P et al. (2011). Microbial diversity associated with four functional groups of benthic reef algae and the reef-building coral Montastraea annularis. Environ Microbiol 13: 1192–1204.

Behrendt L, Larkum AWD, Norman A, Qvortrup K, Chen M, Ralph P et al. (2011). Endolithic chlorophyll d-containing phototrophs. ISME J 5: 1072–1076.

Bertram A, Pattenden G . (2007). Marine metabolites: metal binding and metal complexes of azole-based cyclic peptides of marine origin. Nat Prod Rep 24: 18–30.

Böer SI, Hedtkamp SIC, van Beusekom JEE, Fuhrman JA, Boetius A, Ramette A . (2009). Time- and sediment depth-related variations in bacterial diversity and community structure in subtidal sands. ISME J 3: 780–791.

Bolhuis H, Stal LJ . (2011). Analysis of bacterial and archaeal diversity in coastal microbial mats using massive parallel 16S rRNA gene tag sequencing. ISME J 5: 1701–1712.

Degnan BM, Hawkins CJ, Lavin MF, McCaffrey EJ, Parry DL, Van den Brenk AL et al. (1989). New cyclic peptides with cytotoxic activity from the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J Med Chem 32: 1349–1354.

Donia MS, Fricke WF, Ravel J, Schmidt EW . (2011). Variation in tropical reef symbiont metagenomes defined by secondary metabolism. PLoS One 6: e17897.

Erwin PM, López-Legentil S, Schuhmann PW . (2010). The pharmaceutical value of marine biodiversity for anti-cancer drug discovery. Ecol Econ 70: 445–451.

Ferguson SJ, Jackson JB, McEwan AG . (1987). Anaerobic respiration in the Rhodospirillaceae: characterisation of pathways and evaluation of roles in redox balancing during photosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 46: 117–143.

Hanna C, Schönberg L, De Beer D, Lawton A . (2005). Oxygen microsensor studies on zooxanthellate clionaid sponges from the Costa Brava, Mediterranean Sea. J Phycol 41: 774–779.

Hirose E, Maruyama T . (2004). What are the benefits in the ascidian-Prochloron symbiosis? Endocytobiosis Cell Res 15: 51–62.

Hirose E, Neilan BA, Schmidt EW, Murakami A . (2009). Enigmatic life and evolution of Prochloron and related cyanobacteria inhabiting colonial ascidians. In: Gault PM, Marler HJ (eds). Handbook on Cyanobacteria: Biochemistry, Biotechnology and Applications, 1st edn. Nova Science Pub Inc., pp 161–189.

Hoffmann F, Røy H, Bayer K, Hentschel U, Pfannkuchen M, Brümmer F et al. (2008). Oxygen dynamics and transport in the Mediterranean sponge Aplysina aerophoba. Mar Biol 153: 1257–1264.

Holmsgaard PN, Norman A, Hede SC, Poulsen PHB, Al-Soud WA, Hansen LH et al. (2011). Bias in bacterial diversity as a result of Nycodenz extraction from bulk soil. Soil Biol Biochem 43: 2152–2159.

Imhoff JF, Hiraishi A . (2005). Aerobic bacteria containing Bacteriochlorophyll and belonging to the Alphaproteobacteria. In: Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT, Garrity GM (eds). Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Vol. 2, 2nd edn. Springer: USA, pp 133–136.

Jensen SI, Steunou A-S, Bhaya D, Kuhl M, Grossman AR . (2011). In situ dynamics of O2, pH and cyanobacterial transcripts associated with CCM, photosynthesis and detoxification of ROS. ISME J 5: 317–328.

Jüttner F, Todorova AK, Walch N, von Philipsborn W . (2001). Nostocyclamide M: a cyanobacterial cyclic peptide with allelopathic activity from Nostoc 31. Phytochemistry 57: 613–619.

Kashiyama Y, Miyashita H, Ohkubo S, Ogawa NO, Chikaraish iY, Takano Y . (2008). Evidence for global chlorophyll d. Science 321: 658.

Kline TC, Lewin RA . (1999). Natural N-15/N-14 abundance as evidence for N2 fixation by Prochloron (Prochlorophyta) endosymbiotic with didemnid ascidians. Symbiosis 26: 193–198.

Kühl M . (2005). Optical microsensors for analysis of microbial communities. Meth Enzymol 397: 166–199.

Kühl M, Chen M, Ralph PJ, Schreiber U, Larkum AWD . (2005). A niche for cyanobacteria containing chlorophyll d. Nature 433: 820.

Kühl M, Cohen Y, Dalsgaard T, Jørgensen BB, Revsbech NP . (1995). Microenvironment and photosynthesis of zooxanthellae in scleractinian corals studied with microsensors for 02, pH and light. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 117: 159–172.

Kühl M, Jørgensen BB . (1994). The light field of microbenthic communities: radiance distribution and microscale optics of sandy coastal sediments. Limnol Oceanogr 39: 1368–1398.

Kühl M, Larkum AWD . (2002). The microenvironment and photosynthetic performance of Prochloron sp. in symbiosis with didemnid ascidians. In: Seckbach J (ed). Cellular origin and life in extreme habitats: Symbioses, mechanisms and model systems. Vol. 3, 1st edn. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, pp 273–290.

Kühl M, Lassen C, Jørgensen BB . (1994). Light penetration and light intensity in sandy marine sediments measured with irradiance and scalar irradiance fibre-optic microprobes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 105: 139–148.

Kühl M, Polerecky L . (2008). Functional and structural imaging of phototrophic microbial communities and symbioses. Aquat Microb Ecol 53: 99–118.

Kunin V, Engelbrektson A, Ochman H, Hugenholtz P . (2010). Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates. Environ Microbiol 12: 118–123.

Kunin V, Raes J, Harris JK, Spear JR, Walker JJ, Ivanova N et al. (2008). Millimeter-scale genetic gradients and community-level molecular convergence in a hypersaline microbial mat. Mol Syst Biol 4: 198.

Larkum AWD, Kühl M . (2005). Chlorophyll d: the puzzle resolved. Trends Plant Sci 10: 355–357.

Lewin RA . (1981). Prochloron and the theory of symbiogenesis. Ann NY Acad Sci 361: 325–329.

Lewin RA, Cheng L . (1985). Ecology of Prochloron, a symbiotic alga in ascidians of coral reef areas. Proc Fifth Int Coral Reef Congress 5: 95–101.

Ley RE, Harris JK, Wilcox J, Spear JR, Miller SR, Bebout BM et al. (2006). Unexpected diversity and complexity of the Guerrero Negro hypersaline microbial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 3685–3695.

López-Legentil S, Song B, Bosch M, Pawlik JR, Turon X . (2011). Cyanobacterial diversity and a new Acaryochloris-like symbiont from Bahamian sea-squirts. PLoS One 6: e23938.

Lüdemann H, Arth I, Liesack W . (2000). Spatial changes in the bacterial community structure along a vertical oxygen gradient in flooded paddy soil cores. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 754–762.

Magnusson SH, Fine M, Kuehl M . (2007). Light microclimate of endolithic phototrophs in the scleractinian corals Montipora monasteriata and Porites cylindrica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 332: 119–128.

Martínez-García M, Díaz-Valdés M, Antón J . (2009). Diversity of pufM genes, involved in aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis, in the bacterial communities associated with colonial ascidians. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 71: 387–398.

Martínez-García M, Koblížek M, López-Legentil S, Antón J . (2011). Epibiosis of oxygenic phototrophs containing chlorophylls a, b, c and d on the colonial ascidian Cystodytes dellechiajei. Microb Ecol 61: 13–19.

Menezes CBA, Bonugli-Santos RC, Miqueletto PB, Passarini MRZ, Silva CHD, Justo MR et al. (2010). Microbial diversity associated with algae, ascidians and sponges from the north coast of São Paulo state, Brazil. Microbiol Res 165: 466–482.

Michiels K, Vanderleyden J, Gool A . (1989). Azospirillum; plant root associations: a review. Biol Fertil Soils 8: 356–368.

Nabti E, Sahnoune M, Adjrad S, Van Dommelen A, Ghoul M, Schmid M et al. (2007). A halophilic and osmotolerant Azospirillum brasilense strain from Algerian soil restores wheat growth under saline conditions. Eng Life Sci 7: 354–360.

Nabti E, Sahnoune M, Ghoul M, Fischer D, Hofmann A, Rothballer M et al. (2010). Restoration of growth of durum wheat (Triticum durum var. waha) under Saline conditions due to inoculation with the Rhizosphere Bacterium Azospirillum brasilense; NH and extracts of the marine alga; Ulva lactuca. J Plant Growth Regul 29: 6–22-22.

Ogi T, Margiastuti P, Teruya T, Taira J, Suenaga K, Ueda K . (2009). Isolation of C11 cyclopentenones from two didemnid species, Lissoclinum sp. and Diplosoma sp. Mar Drugs 7: 816–832.

Paerl HW . (1984). N2 fixation (nitrogenase activity) attributable to a specific Prochloron (Prochlorophyta)-ascidian association in Palau, Micronesia. Mar Biol 81: 251–254.

Pedrós-Alió C . (2006). Marine microbial diversity: can it be determined? Trend Microbiol 14: 257–263.

Pegau WS, Gray D, Zaneveld JRV . (1997). Absorption and attenuation of visible and near-infrared light in water: dependence on temperature and salinity. Appl Opt 36: 6035–6046.

Pegau WS, Zaneveld JRV . (1993). Temperature-dependent absorption of water in the red and near-infrared portions of the spectrum. Limnol Oceanogr 38: 188–192.

Polerecky L, Bissett A, Al-Najjar M, Faerber P, Osmers H, Suci PA et al. (2009). Modular spectral imaging system for discrimination of pigments in cells and microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 758–771.

Reeder J, Knight R . (2009). The ‘rare biosphere’: a reality check. Nat Meth 6: 636–637.

Salomon CE, Faulkner DJ . (2002). Localization studies of bioactive cyclic peptides in the ascidian Lissoclinum patella. J Nat Prod 65: 689–692.

Samuel PM . (2000). Developments in aquatic microbiology. Int Microbiol 3: 203–211.

Schink B, Pfennig N . (1982). Propionigenium modestum gen. nov. sp. nov. a new strictly anaerobic, nonsporing bacterium growing on succinate. Arch Microbiol 133: 209–216.

Schloss PD, Handelsman J . (2005). Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 1501–1506.

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB et al. (2009). Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 7537–7541.

Schmidt EW, Nelson JT, Rasko DA, Sudek S, Eisen JA, Haygood MG et al. (2005). Patellamide A and C biosynthesis by a microcin-like pathway in Prochloron didemni, the cyanobacterial symbiont of Lissoclinum patella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 7315–7320.

Schreiber U . (2004). Pulse-amplitude-modulation (PAM) fluorometry and saturation pulse method: an overview. Chlorophyll fluorescence: a signature of photosynthesis. Vol. 132, 1st edn. In: Papageorgiou GCG (ed.). Kluwer: Dordrecht, pp 279–319.

Sings HL, Rinehart KL . (1996). Compounds produced from potential tunicate-blue-green algal symbiosis: a review. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 17: 385–396.

Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, Welch DM, Huse SM, Neal PR et al. (2006). Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored “rare biosphere”. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12115–12120.

Steunou A-S, Bhaya D, Bateson MM, Melendrez MC, Ward DM, Brecht E et al. (2006). In situ analysis of nitrogen fixation and metabolic switching in unicellular thermophilic cyanobacteria inhabiting hot spring microbial mats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2398–2403.

Steunou A-S, Jensen SI, Brecht E, Becraft ED, Bateson MM, Kilian O et al. (2008). Regulation of nif gene expression and the energetics of N2 fixation over the diel cycle in a hot spring microbial mat. ISME J 2: 364–378.

Suda S, Watanabe MM, Otsuka S, Mahakahant A, Yongmanitchai W, Nopartnaraporn N et al. (2002). Taxonomic revision of water-bloom-forming species of oscillatorioid cyanobacteria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52: 1577–1595.

Swingley WD, Chen M, Cheung PC, Conrad AL, Dejesa LC, Hao J et al. (2008). Niche adaptation and genome expansion in the chlorophyll d-producing cyanobacterium Acaryochloris marina. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 2005–2010.

Tait E, Carman M, Sievert SM . (2007). Phylogenetic diversity of bacteria associated with ascidians in Eel Pond (Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA). J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 342: 138–146.

Taylor M, Hill R, Hentschel U . (2011). Meeting report: 1st international symposium on sponge microbiology. Mar Biotechnol 13: 1057–1061.

Taylor MW, Radax R, Steger D, Wagner M . (2007). Sponge-associated microorganisms: evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71: 295–347.

Thomas TRA, Kavlekar DP, LokaBharathi PA . (2010). Marine drugs from sponge-microbe association-a review. Mar Drugs 8: 1417–1468.

Todorova AK, Juettner F, Linden A, Pluess T, von Philipsborn W . (1995). Nostocyclamide: a new macrocyclic, thiazole-containing allelochemical from Nostoc sp. 31 (cyanobacteria). J Org Chem 60: 7891–7895.

Trampe E, Kolbowski J, Schreiber U, Kühl M . (2011). Rapid assessment of different oxygenic phototrophs and single-cell photosynthesis with multicolour variable chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Mar Biol 158: 1667–1675.

Ward DM, Bateson, M. M., Ferris MJ, Kühl M, Wieland A et al. (2006). Cyanobacterial ecotypes in the microbial mat community of Mushroom Spring (Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming) as species-like units linking microbial community composition, structure and function. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 361: 1997–2008.

Webster NS, Taylor MW . (2011). Marine sponges and their microbial symbionts: love and other relationships. Environ Microbiol; e-pub ahead of print 28 March 2011; doi:2010.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02460.x.

Whatley JM, Whatley FR . (1981). Chloroplast evolution. New Phytol 87: 233–247.

Youngseob Y, Changsoo L, Jaai K, Seokhwan H . (2005). Group-specific primer and probe sets to detect methanogenic communities using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Biotechnol Bioeng 89: 670–679.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by the Danish Natural Science Research Council (MK) and a PhD grant from the Faculty of Science, University of Copenhagen (LB and MIK). We thank the staff at Heron Island Research Station for excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on The ISME Journal website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Behrendt, L., Larkum, A., Trampe, E. et al. Microbial diversity of biofilm communities in microniches associated with the didemnid ascidian Lissoclinum patella. ISME J 6, 1222–1237 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.181

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.181

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The difference of intestinal microbiota composition between Lantang and Landrace newborn piglets

BMC Veterinary Research (2023)

-

Effects of different grains on bacterial diversity and enzyme activity associated with digestion of starch in the foal stomach

BMC Veterinary Research (2022)

-

Microbial community structure is stratified at the millimeter-scale across the soil–water interface

ISME Communications (2022)

-

Response of Milk Performance, Rumen and Hindgut Microbiome to Dietary Supplementation with Aspergillus oryzae Fermentation Extracts in Dairy Cows

Current Microbiology (2022)

-

Ascidian-associated photosymbionts from Manado, Indonesia: secondary metabolites, bioactivity simulation, and biosynthetic insight

Symbiosis (2021)