Abstract

In the United Kingdom, landfills are the primary anthropogenic source of methane emissions. Methanotrophic bacteria present in landfill biocovers can significantly reduce methane emissions via their capacity to oxidize up to 100% of the methane produced. Several biotic and abiotic parameters regulate methane oxidation in soil, such as oxygen, moisture, methane concentration and temperature. Earthworm-mediated bioturbation has been linked to an increase in methanotrophy in a landfill biocover soil (AC Singer et al., unpublished), but the mechanism of this trophic interaction remains unclear. The aims of this study were to determine the composition of the active methanotroph community and to investigate the interactions between earthworms and bacteria in this landfill biocover soil where the methane oxidation activity was significantly increased by the earthworms. Soil microcosms were incubated with 13C-CH4 and with or without earthworms. DNA and RNA were extracted to characterize the soil bacterial communities, with a particular emphasis on methanotroph populations, using phylogenetic (16S ribosomal RNA) and functional methane monooxygenase (pmoA and mmoX) gene probes, coupled with denaturing gradient-gel electrophoresis, clone libraries and pmoA microarray analyses. Stable isotope probing (SIP) using 13C-CH4 substrate allowed us to link microbial function with identity of bacteria via selective recovery of ‘heavy’ 13C-labelled DNA or RNA and to assess the effect of earthworms on the active methanotroph populations. Both types I and II methanotrophs actively oxidized methane in the landfill soil studied. Results suggested that the earthworm-mediated increase in methane oxidation rate in the landfill soil was more likely to be due to the stimulation of bacterial growth or activity than to substantial shifts in the methanotroph community structure. A Bacteroidetes-related bacterium was identified only in the active bacterial community of earthworm-incubated soil but its capacity to actually oxidize methane has to be proven.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In landfill sites, anaerobic conditions induce high rates of microbially mediated methane production from the decomposition of organic wastes. In the United Kingdom, landfills represent the primary anthropogenic source of methane, the second largest contributor to global warming after CO2. In landfills, which are not equipped with gas collection systems, biocover soils are used to limit methane emissions. Landfill biocover soils have the highest aerobic methane oxidation capacity reported so far in any environment (Whalen et al., 1990; Bogner et al., 1995; Kightley et al., 1995; Borjesson et al., 1998; Streese and Stegmann, 2003). Microorganisms indigenous to landfill caps have the capacity to degrade 10–100% of the methane emitted, thereby representing a major biological sink for this greenhouse gas (Hanson and Hanson, 1996; Spokas et al., 2006). Biological methane oxidation to CO2 can strongly reduce (∼21-fold) climate forcing. Environmental parameters such as oxygenation and methane concentration, moisture content, pH, nitrogen sources and temperature can strongly influence this biological process in soil (Jones and Nedwell, 1993; Boeckx et al., 1996; Chan and Parkin, 2000; Borjesson et al., 2004; Scheutz and Kjeldsen, 2004). Another factor that might influence methane oxidation in soil is the presence of earthworms. Since they profoundly affect the physical and chemical properties of the soil, earthworms are commonly considered as efficient ‘soil engineers’ (Jones et al., 1994). Earthworm burrowing contributes to soil aggregation, oxygenation and mixing. Furthermore, earthworms break down soil organic matter and plant deposition, thereby increasing nutrient turnover. Earthworms excrete several forms of organic and inorganic nitrogen that are used by endogenous and exogenous microorganisms (Needham, 1957; Binet and Trehen, 1992). Soil microbial community size and activity can be affected by earthworm activity (Daniel and Anderson, 1992; Binet and Le Bayon, 1998; Clapperton et al., 2001; Singer et al., 2001; Luepromchai et al., 2002; Tiunov and Dobrovolskaya, 2002; Haynes et al., 2003). However, little is known about the influence of earthworms on bacterial community structure (Schaefer et al., 2005; Mummey et al., 2006).

AC Singer et al. (unpublished) have recently shown an earthworm-mediated increase in methane oxidation rate in both pasture and landfill biocover soils. Improving the efficiency of microbially mediated methane oxidation in landfill soil is crucial for limiting the emission of this greenhouse gas. The aims of the present work were (i) to determine the active methanotroph community in the landfill biocover soil and (ii) to gain insights into the mechanisms by which the earthworms enhance the methane oxidation in this biocover soil, by investigating their effect on the soil bacterial community.

In the last 10 years, novel cultivation techniques have enabled the isolation of previously uncultured methane oxidizers; the characterization of these new genera has led to an improved understanding of methanotroph taxonomy (Bowman et al., 1993, 1997; Bodrossy et al., 1997; Dedysh et al., 1998, 2000, 2002; Wise et al., 1999, 2001). Methanotrophs are currently classified as type I methanotrophs (comprising nine genera among the γ-proteobacteria) and type II methanotrophs (comprising four genera among the α-proteobacteria), according to their intracytoplasmic membrane structure, carbon assimilation pathways, fatty acid composition and phylogeny (Hanson and Hanson, 1996). Types I and II methanotrophs cohabit landfill soils (Wise et al., 1999; Bodrossy et al., 2003; Uz et al., 2003; Crossman et al., 2004; Stralis-Pavese et al., 2004). All methanotrophs possess methane monooxygenase (MMO) that catalyses the first step of methane oxidation. This enzyme exists in two forms, a soluble, cytoplasmic form (sMMO) and a particulate, membrane-bound form (pMMO) (reviewed in Murrell et al., 2000).

The development and application of suitable molecular tools have expanded our view of bacterial diversity in a wide range of natural environments. The 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene has been used for molecular characterization of natural populations of methanotrophs (Murrell et al., 1998; Costello and Lidstrom, 1999; Noll et al., 2005). Because the specific detection of methanotrophs based on their 16S rRNA gene sequence is not always accurate, functional genes of methanotrophs have been extensively targeted in environmental samples including pmoA (encoding the β-subunit of the particulate monooxygenase, pMMO) and mmoX (encoding the α-subunit of the soluble monooxygenase, sMMO). Since pMMO is present in all known methanotrophs with the exception of Methylocella (Dedysh et al., 2000; Theisen et al., 2005) and the phylogeny of pmoA is congruent with 16S rRNA phylogeny (Kolb et al., 2003), pmoA is the most frequent target in molecular ecology studies of methanotrophs (see Dumont and Murrell, 2005 for a review). Recently, a pmoA microarray has been developed by Bodrossy and colleagues, which has proved to be particularly suitable for characterizing the diversity within methanotroph communities (Bodrossy et al., 2003, 2006; Stralis-Pavese et al., 2004).

Stable isotope probing (SIP) is a powerful molecular technique that directly links a defined metabolic process to members of bacterial communities. A 13C-labelled substrate is added to samples from a natural environment and bacteria that actively assimilate this substrate incorporate the 13C into their cellular material, including nucleic acids. The ‘heavy’-labelled nucleic acids can then be separated from the ‘light’ nucleic acids by ultracentrifugation in a caesium chloride (DNA-SIP) or a caesium trifluoroacetate (RNA-SIP, Manefield et al., 2002) gradient. The DNA-SIP technique, has provided valuable insights into the diversity and activity of methylotrophic bacteria (Radajewski et al., 2000) and to methanotrophs in a peat soil (Morris et al., 2002), acidic forest soil (Radajewski et al., 2002), the cave environment (Hutchens et al., 2004), soda lake sediments (Lin et al., 2004) and a landfill soil (Cébron et al., 2007). RNA is considered a much more sensitive marker than DNA because copy numbers are greater and activity of cells is linked directly to synthesis and turnover of RNA (Molin and Givskov, 1999). Furthermore, the isotope incorporation into RNA does not require cell division (for a review see Whiteley et al., 2006).

In this study, SIP has been applied in combination with complementary molecular techniques to investigate the bacterial community structure in a landfill biocover soil and the possible effect of earthworms on these communities, based on 16S rRNA, pmoA and mmoX gene analyses. This work is the first report focusing on the effects of earthworms on active methanotroph communities.

Materials and methods

Landfill soil microcosms

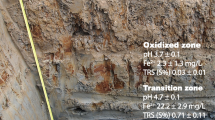

Biocover soil was collected in Ufton Landfill (Warwickshire, UK), in December 2005. The sampling area was covered by grass that was removed before soil was collected at a depth of 10–20 cm. The main physicochemical parameters of the soil (accurate to ±5%) are listed in Table 1. The soil was stored for 1 week at 4°C until use, at which time it was air-dried, sieved (4 mm mesh size) before packing into the wormery (see below).

Earthworms were incubated in plastic tubs (11 × 17 × 6 cm). Approximately 540 g of air-dried, sieved landfill soil, established and maintained at 70% of its water-holding capacity with 250 ml of deionized water was incubated for 2–3 days before the addition of earthworms. Earthworms were incubated in Petri plates for 24 h to evacuate their gut contents before adding to the wormery. Three Eisenia veneta (1.9±0.2 g) were added per wormery, with a ‘no earthworm’ control prepared in parallel. Wormeries were incubated at 19°C in the dark for 17 days before destructive sampling for methane oxidation assays. Aliquots of soil (5 g) from the wormeries were distributed into 118 ml vial bottles. Seven replicate vials were prepared for both the earthworm and control treatments. Vials were spiked with methane to achieve 2% 13C-CH4 (v/v) in the headspace and were incubated at 19°C for 7 days. Methane concentration was measured by gas chromatography over this period. After 7 days incubation with 13C-CH4, soil samples were then stored at −20°C for SIP. Of the seven replicates used for the methane oxidation measurements, four were randomly selected for nucleic acid extraction and molecular analyses. The good reproducibility of these four replicates was confirmed by denaturing gradient-gel electrophoresis (DGGE) using 16S rRNA gene universal bacterial primers and by independent hybridizations on pmoA microarrays (data not shown). For the SIP experiments and clone library construction, the DNA and RNA of these four replicates were pooled, thereby reflecting the replication in the original samples, which were used in methane oxidation experiments.

Soil analysis

Earthworm-incubated soil and control soils were analysed at the end of the experiment, after 17 days incubation with or without earthworms, followed by 7 days incubation with 2% 13C-CH4.

Total carbon and nitrogen content were determined using Dumas combustion with a detection limit of 0.03% N/w and 0.02% C/w, based on a 15 mg sample. Nitrate and ammonia were analysed following extraction in 1 M KCl, with a limit of detection of 0.07 mg NO3− kg soil−1 and 0.10 mg NH4+ kg soil−1. Particle size analysis was carried out using laser diffraction. The results are summarized in Table 1.

DNA and RNA extraction

DNA and RNA were coextracted directly from four soil replicates following the protocol described by Bürgmann et al. (2003) with minor modifications. Briefly, 0.4 g soil, 1 ml extraction buffer (0.2% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), 1 mM 1,4-dithio-DL-threitol [DTT], 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), 0.1 M NaCl, 50 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)) and lysing matrix E (Qbiogene Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) were processed in a bead beater (Bio 101/Savant, Farmingdale, NY, USA) for 45 s at 6 m s−1. After bead beating, samples were put on ice for 5 min, centrifuged (16 000 g, 5 min) at 4°C and 800 μl of the supernatant was extracted with 750 μl of a 1:1 mixture of phenol (pH 8.0) and chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (CIA; 24:1) and then with 750 μl of CIA. Total nucleic acid was precipitated for 1 h at room temperature with 850 μl of RNase-free PEG solution (20% polyethylene glycol, 2.5 M NaCl). After centrifugation (16 000 g, 30 min), the nucleic acid pellets were washed once with cold ethanol (70% v/v). After further centrifugation (16 000 g, 20 min), the pellets were dried at 20°C for 10–20 min and then dissolved in 50 μl of RNase-free water. At this stage, the quality of nucleic acid was determined on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel. DNA was separated from RNA using a Qiagen RNA/DNA mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Nanodrop, Wilmington, DE, USA). Total RNA was treated with 4 U of DNase I (New England Biolabs Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) at 37°C for 2 h and then purified using a Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer and was confirmed to be DNA-free by amplification of 16S rRNA genes with universal primers 27f/907r (94°C 1 min, 60°C 1 min, 72°C 1 min, 35 cycles). No PCR products were obtained except with the appropriate controls.

12C and 13C DNA recovery

DNA extracts from replicates were pooled. The gradients were prepared as described by Neufeld et al. (2007). One gram of caesium chloride (CsCl) was added to 5 μl of DNA (5 μg) diluted in 1 ml of H2O. Then, 100 μl of ethidium bromide (10 mg ml−1) was added to the DNA+CsCl solution in an ultracentrifuge tube (13 × 51 mm, Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA). A control gradient was also prepared containing 2.5 μg each of 12C- and 13C-labelled DNA from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). Heavy and light DNA were then separated by centrifugation at 177 000 g (44 100 r.p.m. using a Beckman rotor VTi 65.2) for 40 h at 20°C.

After centrifugation, heavy and light DNA bands were visualized under UV (365 nm). Heavy DNA was not always visible under UV but its position in the tube was deduced by comparison with the control gradient. Light and heavy DNA were withdrawn gently from the gradient using a 1 ml syringe and hypodermic needle. Ethidium bromide was extracted from the DNA with an equal volume of butanol saturated with Tris-EDTA (TE) (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) buffer (repeated twice). Then DNA was precipitated for 2 h at room temperature with two volumes of PEG solution (30% polyethylene glycol, 1.6 M NaCl) and 3 μl of glycogen to visualize the pellet. After centrifugation for 30 min at 16 000 g at 4°C, pellets were washed with 70% (v/v) ice-cold ethanol. After centrifugation for 15 min at 16 000 g, at 4°C, pellets were air-dried for 10–20 min and then dissolved in 40 μl H2O.

12C and 13C RNA recovery

Replicates of RNA extracts were pooled and rRNA was resolved in a caesium trifluoroacetate (CsTFA) gradient with an average density of 1.795 g ml−1. Centrifugation medium was prepared by mixing 4.655 ml of a 1.953 g ml−1 CsTFA stock solution (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA), 0.165 ml formamide, 0.680 ml of gradient buffer (GB; 100 mM Tris pH 7.8; 100 mM KCl; 1 mM EDTA) and RNA (500 ng) in a total volume of 5.5 ml (RNA volume was subtracted from GB volume). Heavy and light rRNAs were then separated by centrifugation at 130 000 g (37 800 r.p.m. using a Beckman rotor VTi 65.2) for 63 h at 20°C. Centrifuged gradients were fractionated from bottom to top into 12 equal fractions (∼450 μl). A controlled flow rate was achieved by displacing the gradient medium with water at the top of the tube using a peristaltic pump at a flow rate of ∼450 μl min−1. The density of each fraction was checked by weighing 100 μl of each fraction by pipetting (measurement done in triplicate). RNA was precipitated with an equal volume of isopropanol and 3 μl of glycogen (to visualize the pellet). After centrifugation for 30 min at 16 000 g at 4°C, the pellets were washed with 500 μl of 70% (v/v) ice-cold ethanol. After centrifugation for 15 min at 16 000 g at 4°C, the pellets were air-dried for 10–20 min. RNA samples were then dissolved in 20 μl of RNase free-water.

16S rRNA gene amplification and denaturing gradient-gel electrophoresis

rRNA samples from the gradient were reverse transcribed using primer 1492r (Lane, 1991) and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Inc., CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA produced from the light and heavy rRNA recovered from the CsTFA gradient, and DNA samples recovered from CsCl gradient, were used as templates for PCR using three different primer sets. The universal bacterial primer set 341f-GC/907r (Muyzer et al., 1993) was used to amplify 16S rRNA genes from the bacterial community. Amplification was carried out with 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. A seminested PCR strategy (Y Chen et al., unpublished) was used to specifically amplify 16S rRNA genes of either type I or II methanotrophs. First-round amplification was done using type Ir (5′- CCACTGGTGTTCCTTCMGAT ′) and type If (5′- ATGCTTAACACATGCA ′) or type IIr (5′- GTCAARAGCTGGTAAG ′) and type IIf (5′- GGGAMGATAATGACGGT ′) primer sets, specifically targeting types I and II methanotrophs, respectively, using 30 cycles consisting of 95°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. A second round of PCR was performed using 1 μl of the first PCR product as template, using 341f-GC (Muyzer et al., 1993) and the type Ir primer set for the type I methanotrophs and 518f-GC (Muyzer et al., 1993) and the type IIr primer set, for the type II methanotrophs. This second round of PCR was set up according to the procedure above but only for 25 cycles.

The PCR products containing a GC clamp were separated on 6% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels with a 30–70% urea/formamide-denaturing gradient. Gels were run at 85 V for 14 h at 60°C in 1 × TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.3). Gels were then stained for 1 h with 1:10 000 (v/v) SYBR GREEN (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA), rinsed with 1 × TAE and scanned with a storm 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Bands of interest were excised from the gel using cut pipette tips and DNA was dissolved at 4°C in 10 μl sterile H2O overnight. Four microlitres of the dissolved DNA was used as a template for PCR amplification using primer set 341f and 907r. PCR products were then purified using shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) and Exonuclease I (ExoI; Amersham Biosciences) as follows: for one reaction, 1.43 μl of SAP dilution buffer, 1 μl of SAP enzyme (1U μl−1) and 0.075 μl of ExoI enzyme (20U μl−1) were added to 20 μl of PCR product. Samples were incubated for 40 min at 37°C, followed by 15 min at 80°C and then they were stored at 4°C.

pmoA and mmoX clone libraries

Both pmoA and mmoX genes were amplified from the unfractionated pooled DNAs using primer sets mb661r (Costello and Lidstrom, 1999) and A189f (Holmes et al., 1995) and 206F and 886R (Hutchens et al., 2004), respectively, using 30 cycles at 95°C for 1 min, 55°C (pmoA) or 60°C (mmoX) for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. For both genes, the size and purity of the PCR products were checked on 1% (w/v) agarose gels. PCR products were purified using the QIAGEN gel extraction kit and ligated into the PCR II vector (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The positive recombinant clones were screened by direct amplification of the cloned inserts from transformant cells with vector-specific primers M13r and M13f. The clones with correct-sized inserts were digested for 1 h at 37°C using the restriction enzymes EcoRI–PvuII–HincII for pmoA gene and EcoRI–HincII for mmoX gene. Digests were resolved on 2.5% (w/v) agarose gel and grouped into operational taxonomic units (OTUs), based on the restriction pattern obtained and representative clones for each OTU were sequenced.

pmoA microarray experiments

pmoA genes were amplified from unfractionated, light and heavy DNA using primer set A189f/T7-mb661r (Bourne et al., 2001). The T7 promoter attached to the 5′- end of the reverse primer allowed the T7 RNA polymerase to transcribe the DNA templates into RNA in vitro. PCR amplification, in vitro transcription and hybridization protocol were as described by Bodrossy et al. (2003) and modified by Stralis-Pavese et al. (2004).

DNA sequencing and analysis

Sequencing of pmoA and mmoX clones was performed with the M13r (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′) primer targeting the multicloning site of the vector. Double-strand sequencing was performed directly (without any cloning step) on the reamplified and purified 16S rRNA–DGGE bands, using both the primers used for PCR amplification (907r/341f for universal bacterial 16S rRNA genes and types Ir/341f and IIr/518f for types I and II methanotroph 16S rRNA genes, respectively). DNA sequencing was performed using a Dye Terminator kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). DNA sequences were analysed using a 373A automated sequencing system (PE Applied Biosystems). For each DGGE band excised from the gels, a unique sequence was obtained.

Sequences were submitted to a BLAST search (Altschul et al., 1990) and checked for the presence of chimaeras. Chimaeras were not detected for the 16S rRNA gene–DGGE band sequences or for the mmoX sequences, but around 10% of the pmoA sequences were suspected to be chimaeras and were removed from the analysis. Sequences were aligned to related sequences extracted from GenBank using MEGA version 3.1 (Kumar et al., 2004). MEGA 3.1 was also used to estimate evolutionary distances and to construct a phylogenetic tree. Several methods were used to construct trees: for pmoA and mmoX sequences, neighbour-joining with Kimura correction and maximum parsimony based on nucleotide sequence analysis, and neighbour-joining with Poisson correction and maximum parsimony based on amino-acid derived sequences analysis; for 16S rRNA gene phylogeny, neighbour-joining with Kimura correction and maximum parsimony. For all the genes, the different methods tested gave similar results.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The GenBank accession numbers for the nucleotide sequences determined in this study are EF472919 to EF472921 for the 16S rRNA gene sequences, EF472933 to EF472943 for the pmoA sequences and EF472922 to EF472932 for the mmoX sequences.

Results

Effect of earthworms on methane oxidation in the landfill biocover soil and on soil characteristics

After incubation for 168 h with 13C-methane, the earthworm-incubated soil removed significantly more methane (67%) than the control soil (52%, n=15, P=0.007; AC Singer et al., unpublished).

The nitrate and ammonia contents of soil incubated with earthworms were respectively higher and lower than that in soil without earthworms. Total nitrogen and carbon contents were comparable. Earthworm-incubated soil consisted mainly of silt particles, while soil without earthworms consisted mainly of sand particles. The percentage of clay was generally higher (16%) in the earthworm-incubated soil (Table 1).

Bacterial community fingerprints

For RNA-SIP, the densities of the ‘heavy’ and ‘light’ fractions were 1.80 and 1.77 g ml−1, respectively. DGGE analysis was performed on light and heavy DNA and RNA fractions recovered from the SIP experiments, using different primer sets targeting 16S RNA genes. Universal bacterial 16S rRNA gene PCR primers gave complex and similar DGGE profiles with 12C-DNA and 12C-RNA samples from the microcosms containing worms (+worms) and the corresponding control (−worms). Profiles corresponding to 13C-DNA or RNA were less complex, comprising of only a few intense bands corresponding to the bacteria that have incorporated the 13C in their nucleic acids. In the 13C-RNA profiles, the 12C-RNA background was still visible under the main 13C bands. Two major DGGE bands were common to both −worms and +worms in the 13C-DNA and 13C-RNA DGGE profiles, whereas one band was specific to the +worms in 13C-DNA and 13C-RNA profiles (Figure 1). For both DNA- and RNA-DGGE, these three bands were excised from the gels, sequenced, and their phylogenetic affiliations were determined. The sequences corresponding to the bands excised from the DNA-DGGE gel were similar to those corresponding to the bands excised from the RNA-DGGE gel (100% identity). The two DGGE bands common to both 13C profiles of −worms and +worms samples corresponded to Methylobacter- and Methylosarcina- (Wise et al., 2001) related 16S rRNA gene sequences, clustering among the type I methanotrophs. The band specific to the DGGE profiles obtained with 13C-DNA and 13C-RNA from the +worms microcosm sample corresponded to a Bacteroidetes-related 16S rRNA sequence (Figure 2).

Denaturing gradient-gel electrophoresis (DGGE) targeting the bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA genes obtained for the 12C- and 13C-DNA fractions (a) and the 12C- and 13C-RNA fractions (b) from landfill cover soil samples incubated without (−worms) and with worms (+worms). Lane L corresponds to a molecular mass ladder. Black arrows indicate DGGE bands that have been sequenced.

Phylogenetic neighbour-joining tree of partial 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) sequences, showing the relationship of sequences from denaturing gradient-gel electrophoresis (DGGE) bands obtained with both 13C-DNA and 13C-RNA samples to sequences of pure cultures and 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained in other cultivation-independent studies. DGGE band-derived sequences from this study are indicated by boldface type. Only bootstrap values >50% are indicated. Scale bar=0.02 change per base position.

Primers specifically targeting 16S rRNA genes from type I or II methanotrophs were used to investigate the effect of earthworms on methanotroph community structure. As observed with the universal bacterial 16S rRNA gene primers, the 13C-DNA and 13C-RNA profiles obtained with type I methanotroph-specific 16S rRNA gene primers were mainly composed of two intense bands (Figure 3) in contrast to the 12C- profiles that appeared more complex. Sequencing of these 16S rRNA genes from the DGGE gels showed that the two bands dominating the 13C profiles corresponded to the methanotroph sequences identified in the 13C profiles using universal bacterial 16S rRNA gene primers: Methylobacter- and Methylosarcina-related 16S rRNA gene sequences. Whereas the DGGE profiles obtained with 13C-DNA and 13C-RNA from the −worms and +worms microcosms were similar, some slight differences were observed in the 12C-DNA 16S rRNA gene DGGE profiles (Figure 3).

DGGE profiles obtained for the 12C- and 13C-DNA and RNA with type II methanotroph-specific 16S rRNA gene PCR primers were similar, for all the samples tested (data not shown), and contained two dominant bands. Sequencing of these bands excised from both heavy- and light-fraction DGGE profiles revealed that they corresponded to highly similar sequences (99% identity). Phylogenetic analysis assigned these two 16S rRNA gene sequences to Methylocystis-related bacteria (data not shown).

pmoA and mmoX diversity

To complement the data obtained with 16S rRNA gene analyses, the distributions of pmoA and mmoX, two key genes for methanotrophy, were investigated in both −worms and +worms samples using complementary molecular biology techniques. Clone libraries were constructed for both genes using DNA extracted from −worms and +worms microcosm soil samples.

pmoA diversity

Around 10% of the pmoA sequences were suspected to be chimaeras and were removed from the clone library analysis. Forty-five pmoA clones obtained from −worms microcosm and 47 pmoA clones obtained from +worms microcosm clones were grouped into eight OTUs according to their restriction patterns. At least one representative of each OTU (two for OTUs containing more than five clones, three for OTUs containing more than ten clones) was sequenced. Phylogenetic analysis of pmoA sequences indicated that two OTUs were dominant in pmoA libraries constructed using DNA from both −worms and +worms libraries, corresponding to Methylomicrobium/Methylosarcina (OTU1) and Methylocystis (OTU2)-related pmoA sequences. In both libraries, type Ia pmoA sequences represented 60 and 66% of the pmoA clones in the −worms and +worms libraries, respectively, and were Methylomicrobium/Methylosarcina- and Methylobacter-related sequences. Type II methanotrophs accounted for 40 and 34% of the −worms and +worms clones, respectively, and were only represented by Methylocystis-related pmoA sequences (Figure 4). No pmoA sequences from the type Ib methanotroph genera Methylocaldum, Methylothermus, Methylococcus or the type Ia genus Methylomonas or the type II genus Methylosinus were found.

Phylogenetic neighbour-joining tree of partial PmoA sequences derived from the pmoA clone libraries (Poisson correction). The percentage of each operational taxonomic unit (OTU) among each library is indicated within parentheses, ‘−w’ indicates −worms library and ‘+w’ indicates +worms library. Only bootstrap values >50% are indicated. Scale bar=0.05 change per base position.

To complement data obtained from pmoA clone libraries, a pmoA microarray was used to investigate the diversity of this functional gene at different taxonomic levels. Hybridization signal patterns reflected the high diversity of pmoA sequences belonging to both types I and II groups retrieved in all of the DNA samples (Figure 5). For the type I methanotrophs, high hybridization signal intensities were observed for probes targeting the pmoA from the genera Methylobacter, Methylomicrobium and Methylosarcina (type Ia) and lower signal intensity was obtained for probe targeting genus Methylocaldum (type Ib). Since high signal intensity was obtained with the probe targeting both the genera Methylomicrobium and Methylosarcina (Mmb_562) and low signal intensity was obtained with the probe targeting only the genus Methylomicrobium (Mmb_303), it is likely that Methylosarcina and related bacteria are responsible for the high signal intensity obtained with probe Mmb_562. For the type II methanotrophs, very high hybridization signals were obtained for probes targeting the pmoA from the genera Methylocystis and Methylosinus, suggesting their relative high abundance in all of the samples. Interestingly, three genera that were not detected at all in the pmoA clone libraries have been detected with the pmoA microarray: Methylomonas (type Ia, probe P_Mm531), Methylocaldum (type Ib, probe Mcl408) and Methylosinus (type II). Two probes, targeting pmoA from the genus Methylocaldum (McI408) and the Upland soil cluster Gamma (P_USCG-225), hybridized only with templates generated from the unfractionated DNA and the 12C-DNA of both samples (not for the 13C-DNA). Considering the 13C-DNA samples, some probes targeting type Ia methanotrophs showed a stronger hybridization signal for the +worms sample than for the −worms sample: Mmb303 (Methylomicrobium-specific probe), P_Mm531 (Methylomonas-specific probe) and P_MbSL#3–300 (Methylobacter-specific probe). This increase in the relative abundance of type Ia methanotroph signals in the 13C-DNA of the +worms sample is supported by the fact that a highest hybridization signal was also observed for the generalist probe for type Ia methanotrophs (O_Ia193).

Microarray results showing hybridization patterns obtained for 12C and 13C DNA of both −worms and +worms samples with the microarray pmoA probe set. Relative signal intensities are indicated by the different colours as shown on the colour bar (a value of 1 corresponding to the maximum achievable signal for an individual probe).

mmoX diversity

Eighty-eight and 95 mmoX clones containing the correct size insert derived from DNA extracted from the −worms and +worms microcosms, respectively, were analysed by restriction fragment-length polymorphism (RFLP). These clones grouped into three distinct OTUs. The dominant OTU (OTU1), which represented 85 and 81% of the −worms and the +worms clones, respectively, corresponded to members of type II methanotrophs related to Methylocystis species (Figure 6). These mmoX sequences were also closely related to mmoX sequences previously recovered from the same Ufton landfill biocover soil (JC Murrell et al., unpublished). OTU2 and OTU3 could not be affiliated to mmoX from any known methanotrophs, since the highest percentage of identity to other mmoX nucleotide sequences was 83%. However, based on phylogenetic analysis, OTU2, which represented 7 and 16% of the −worms and +worms clones, respectively, is probably related to type I methanotrophs; whereas OTU3, which represented 8 and 3% of the −worms and +worms clones, respectively, is probably related to type II methanotrophs. These two OTUs may correspond to mmoX sequences of uncultivated methanotrophs (Figure 6). Type II-related mmoX sequences were dominant in both libraries, whereas type I-related mmoX accounted for 7 and 16% of the −worms and +worms microcosm-derived clones, respectively.

Phylogenetic neighbour-joining tree of partial MmoX-derived sequences from the mmoX clone libraries (Poisson correction). The percentage of each operational taxonomic unit (OTU) among each library is indicated within parentheses, ‘−w’ indicates −worms library and ‘+w’ indicates +worms library. Only bootstrap values >50% are indicated. Scale bar=0.05 change per base position.

Discussion

For a better control of methane emissions, landfill management practice requires a detailed knowledge of the microorganisms involved in methane oxidation and a better understanding of the environmental parameters that regulate this biological process. The mechanism by which earthworms enhance methane oxidation efficiency has been investigated, with particular emphasis on the active component of the bacterial methanotroph community.

Methanotroph diversity in the landfill soil

On the basis of pmoA clone libraries and particularly on pmoA microarray results, a high diversity of pmoA sequences related to both types I and II methanotrophs has been retrieved as reported for other landfill biocover soils (Wise et al., 1999; Bodrossy et al., 2003; Uz et al., 2003; Crossman et al., 2004; Stralis-Pavese et al., 2004). In the Ufton landfill biocover soil, types I and II methanotrophs seemed to be highly diverse with several genera being detected, in particular, after pmoA microarray analysis. Conversely, the diversity of mmoX-carrying methanotrophs was low, with more than 80% of the sequences relating to Methylocystis sp. sequences.

Active methanotrophs identified in 13C-DNA and 13C-RNA by DGGE were related to 16S rRNA from the type I genera Methylobacter and Methylosarcina and to 16S rRNA from the type II genus Methylocystis. These results are in agreement with pmoA hybridization patterns obtained with the 13C-DNA. On the basis of previous SIP experiments, bacteria that actively oxidize methane were identified as belonging to a broad range of type I and type II methanotrophs in a peat soil (Morris et al., 2002) and in Movile cave (Hutchens et al., 2004), whereas it has been hypothesized that only type I methanotrophs were responsible for the majority of CH4 oxidation in Russian soda lake sediments (Lin et al., 2004).

The different molecular methods used in this study identified the same dominant and active methanotrophs. Other studies (Costello and Lidstrom, 1999; Horz et al., 2001) have similarly concluded that 16S rRNA and pmoA-based methods gave similar methanotroph community structure profiles, both approaches being complementary. The congruent results obtained with the clone libraries and the microarray are confirmed by the fact that the dominant pmoA clones had perfect sequence matches with the most intensely hybridized pmoA probes (data not shown). However, microarrays gave a more complete view of the pmoA diversity in the soil samples studied, with a higher diversity of pmoA sequences retrieved, confirming the suitability of this high throughput method for assessing a wider diversity of pmoA genes present in the target environment (while pmoA gene libraries may only reveal the most abundant pmoA phylotypes). This difference observed in terms of the diversity recovered may also result from cloning bias and the low number of clones analysed, resulting in a poor representation of the methanotroph diversity in the clone libraries. Analysis of type I DGGE, 12C-DNA and RNA profiles of both samples suggested a high diversity of type I, whereas only few distinct bands were observed in the 13C DNA and RNA profiles, suggesting that the dominant member of the bacterial community was not necessarily active. On the contrary, pmoA microarray results showed only few differences between hybridization patterns for 12C and 13C samples, suggesting that almost all of the methanotrophs detected were active. This could be due to the lack of specificity of type I 16S rRNA gene primers when applied to a complex bacterial community. In 12C-DNA or RNA, the proportion of type I methanotrophs among total bacteria might be too small to avoid the amplification of nonmethanotrophic bacteria. Hybridization of both 12C- and 13C-DNA to the pmoA microarray allowed a more precise discrimination between the active and the non-active methanotrophs. The hybridization signals obtained for the Methylocaldum (Mcl408) and Upland Soil Cluster gamma probes (P-USCG-225 and P-USCG-225b; Figure 5) only with the unfractionated and the 12C-DNA, but not with the 13C-DNA samples, suggested that these bacteria were present in the soil, but were not actively oxidizing methane.

In this study, RNA-SIP and DNA-SIP have been compared. Lueders et al. (2004) combined RNA- and DNA-SIP to monitor activation and temporal dynamics of methylotrophs in soil. The authors suggested that after 6 days of incubation with labelled substrate, RNA-SIP recovered the initially active bacteria, whereas a specific enriched methylotroph was identified after 42 days of incubation using DNA-SIP. A recent publication also demonstrated the faster incorporation of label into RNAs (Manefield et al., 2007). However, DNA-SIP sensitivity has been improved, and the amounts of substrate as well as the incubation times have been significantly optimized (Neufeld et al., 2007). In our study, 7 days of incubation with 11 μmol of 13C-CH4 g−1 soil were sufficient for efficient labelling of both DNA and RNA and results obtained with DNA- and RNA-SIP based on 16S rRNA DGGE analyses were quite similar. This suggests that, after 7 days incubation with 13C-CH4, all the active methane-consuming bacteria synthesized DNA. However, it is not excluded that results would have been different if RNA- and DNA-SIP had been compared for successive earlier time points. Slight differences in 12C profiles between RNA- and DNA-based DGGE profiles were observed, suggesting that the dominant member of the bacterial community was not necessarily active.

Earthworm effects on bacterial community structure

The Bacteroidetes-related bacterium identified in the 13C-DNA and RNA of earthworm-incubated soil was the only obvious modification in the total bacterial community structure observed by DGGE. It is the first time that Bacteroidetes have been identified as potentially playing a role in methane oxidation. Even if Bacteroidetes have been identified in some methane-rich environments (Scholten-Koerselman et al., 1986; Reed et al., 2002, 2006), there is lack of evidence concerning the possible capacity of the Bacteroidetes we identified to oxidize methane. This result might be due to a cross-feeding phenomenon, that is the consumption by the Bacteroidetes-related bacteria of a labelled by-product produced by the methanotrophs during methane oxidation. An alternative hypothesis is that due to food web interactions, dead 13C-labelled methanotrophs have been consumed by Bacteroidetes. Further investigations are necessary to determine if this bacterium can oxidize methane.

Microarray data are semiquantitative, thereby enabling the direct comparison of the relative abundance of target sequences (here pmoA sequences) in a number of environmental samples (discussed in Bodrossy et al., 2003; Neufeld et al., 2006). On the basis of pmoA microarray results obtained with 13C-DNA, the relative abundance of type Ia methanotrophs appeared higher in the earthworm-incubated soil. This is suggested since the highest hybridization signals were observed for the generalist probe targeting the type Ia (O_Ia193) pmoA and other pmoA probes targeting several genera of type Ia methanotrophs (that is the Methylomicrobium probe Mmb303, Methylomonas probe P_Mm531 and Methylobacter probe P_MbSL#3–300). Furthermore, considering results from analysis of both pmoA and mmoX libraries, the percentage of type I methanotroph-related sequences was higher in the earthworm-incubated soil. These differences should not be considered as significant since clone libraries are not quantitative but this trend supported the microarray results, which indicate the greater abundance of pmoA sequence types in DNA or RNA samples, suggesting that earthworms might have stimulated growth or activity of type I methanotrophs. These finding are in agreement with the assumption that type I methanotrophs probably react faster to changing conditions than type II methanotrophs, owing to a higher growth rate (Graham et al., 1993; Bodelier et al., 2000; Henckel et al., 2000). This growth or stimulation of activity could be correlated with a nitrogen supply and/or an improved nutrient availability directly linked to earthworm activity (Needham, 1957; Buse, 1990). In this study, the relative amounts of ammonia and nitrate were strongly influenced by the earthworm activity (Table 1). The highest nitrate content and the lowest ammonia content in the earthworm-incubated soil suggest a possible stimulation of nitrifier activity. A higher number of nitrifiers have been reported in earthworm burrow walls (Parkin and Berry, 1999), as well as in casts (Mulongoy and Bedoret, 1989) in comparison with the underlying soil, which was correlated to a higher content of mineral nitrogen in the soil. Nitrifiers possess the ammonia monooxygenase, an enzyme that is evolutionary related to the MMO, and can to some extent co-oxidize methane. However, the contribution of nitrifiers to the global methane cycle is unclear and sometimes controversial (Holmes et al., 1995). Further investigations on the nitrifier communities will be necessary to determine the extent to which this group of bacteria could be involved in the earthworm-mediated increase in methane oxidation rates observed in the landfill soil studied.

Conclusions

We proposed the hypothesis that earthworms could stimulate the growth or the activity of methanotrophs. We showed that the earthworm-mediated increase of methane oxidation in the landfill biocover soil only weakly correlated with a shift in the structure of the active methanotroph population. Future work needs to focus on the relationship between this earthworm effect on enhanced methane oxidation in landfill cover soil and this effect on bacterial activity and growth. The possible contribution of an enriched population of nitrifying bacteria to methane oxidation also requires further investigation.

References

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ . (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215: 403–410.

Binet F, Le Bayon RC . (1998). Space–time dynamics in situ of earthworm casts under temperate cultivated soils. Soil Biol Biochem 31: 85–93.

Binet F, Trehen P . (1992). Experimental microcosm study of the role of Lumbricus terrestris (oligochaeta:lumbricidae) on nitrogen dynamics in cultivated soils. Soil Biol Biochem 24: 1501–1506.

Bodelier PL, Roslev P, Henckel T, Frenzel P . (2000). Stimulation by ammonium-based fertilizers of methane oxidation in soil around rice roots. Nature 403: 421–424.

Bodrossy L, Holmes EM, Holmes AJ, Kovacs KL, Murrell JC . (1997). Analysis of 16S rRNA and methane monooxygenase gene sequences reveals a novel group of thermotolerant and thermophilic methanotrophs, Methylocaldum gen. nov. Arch Microbiol 168: 493–503.

Bodrossy L, Stralis-Pavese N, Konrad-Koszler M, Weilharter A, Reichenauer TG, Schofer D et al. (2006). mRNA-based parallel detection of active methanotroph populations by use of a diagnostic microarray. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 1672–1676.

Bodrossy L, Stralis-Pavese N, Murrell JC, Radajewski S, Weilharter A, Sessitsch A . (2003). Development and validation of a diagnostic microbial microarray for methanotrophs. Environ Microbiol 5: 566–582.

Boeckx P, Van Cleemput O, Villaralvo I . (1996). Methane emission from a landfill and the methane oxidising capacity of its covering soil. Soil Biol Biochem 28: 1397–1405.

Bogner J, Spokas K, Burton E, Sweeney R, Corona V . (1995). Landfills as atmospheric methane sources and sinks. Chemosphere 31: 4119–4130.

Borjesson G, Sundh I, Svensson B . (2004). Microbial oxidation of CH4 at different temperatures in landfill cover soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 48: 305–312.

Borjesson G, Sundh I, Tunlid A, Frostegard A, Svensson BH . (1998). Microbial oxidation of CH4 at high partial pressures in an organic landfill cover soil under different moisture regimes. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 26: 207–217.

Bourne DG, McDonald IR, Murrell JC . (2001). Comparison of pmoA PCR primer sets as tools for investigating methanotroph diversity in three Danish soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 3802–3809.

Bowman JP, McCammon SA, Skerratt JH . (1997). Methylosphaera hansonii gen. nov., sp. nov., a psychrophilic, group I methanotroph from Antarctic marine-salinity, meromictic lakes. Microbiology 143: 1451–1459.

Bowman JP, Sly LI, Nichols PD, Hayward AC . (1993). Revised taxonomy of the methanotrophs: description of Methylobacter gen. nov., emendation of Methylococcus, validation of Methylosinus and Methylocystis species, and a proposal that the family Methylococcaceae includes only the group I methanotrophs. Int J Syst Bacteriol 43: 735–753.

Bürgmann H, Widmer F, Sigler WV, Zeyer J . (2003). mRNA extraction and reverse transcription-PCR protocol for detection of nifH gene expression by Azotobacter vinelandii in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 1928–1935.

Buse A . (1990). Influence of earthworms on nitrogen fluxes and plant growth in cores taken from variously managed upland pastures. Soil Biol Biochem 22: 775–780.

Cébron A, Bodrossy L, Chen Y, Singer AC, Thompson IP, Prosser JI et al. (2007). Identity of active methanotrophs in landfill cover soil as revealed by DNA-stable isotope probing. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 62: 12–23.

Chan ASK, Parkin TB . (2000). Evaluation of potential inhibitors of methanogenesis and methane oxidation in a landfill cover soil. Soil Biol Biochem 32: 1581–1590.

Clapperton MJ, Lee NO, Binet F, Conner RL . (2001). Earthworms indirectly reduce the effects of take-all (Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici) on soft white spring wheat (Triticum aestivum cv. Fielder). Soil Biol Biochem 33: 1531–1538.

Costello AM, Lidstrom ME . (1999). Molecular characterization of functional and phylogenetic genes from natural populations of methanotrophs in lake sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 5066–5074.

Crossman Z, Abraham F, Evershed RP . (2004). Stable isotope pulse-chasing and compound specific stable carbon isotope analysis of phospholipid fatty acids to assess methane oxidizing bacterial populations in landfill cover soils. Environ Sci Technol 38: 1359–1367.

Daniel O, Anderson JM . (1992). Microbial biomass and activity in contrasting soil materials after passage through the gut of the earthworm Lumbricus rubellus Hoffmeister. Soil Biol Biochem 24: 465–470.

Dedysh SN, Khmelenina VN, Suzina NE, Trotsenko YA, Semrau JD, Liesack W et al. (2002). Methylocapsa acidiphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel methane-oxidizing and dinitrogen-fixing acidophilic bacterium from Sphagnum bog. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52: 251–261.

Dedysh SN, Liesack W, Khmelenina VN, Suzina NE, Trotsenko YA, Semrau JD et al. (2000). Methylocella palustris gen. nov., sp. nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bogs, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 50: 955–969.

Dedysh SN, Panikov NS, Liesack W, Grosskopf R, Zhou J, Tiedje JM . (1998). Isolation of acidophilic methane-oxidizing bacteria from northern peat wetlands. Science 282: 281–284.

Dumont MG, Murrell JC . (2005). Community-level analysis: key genes of aerobic methane oxidation. In: Leadbetter J (ed). Methods in Enzymology. SPI: St Louis, MO, USA, vol. 397, pp 413–427.

Graham DW, Chaudhary JA, Hanson RS, Arnold RG . (1993). Factors affecting competition between type I and type II methanotrophs in two-organism continuous-flow reactors. Microb Ecol 25: 1–18.

Hanson RS, Hanson TE . (1996). Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol Rev 60: 439–471.

Haynes RJ, Fraser PM, Piercy JE, Tregurtha RJ . (2003). Casts of Aporrectodea caliginosa (Savigny) and Lumbricus rubellus (Hoffmeister) differ in microbial activity, nutrient availability and aggregate stability: The 7th International Symposium on Earthworm Ecology, Cardiff, Wales 2002. Pedobiologia 47: 882–887.

Henckel T, Roslev P, Conrad R . (2000). Effects of O2 and CH4 on presence and activity of the indigenous methanotrophic community in rice field soil. Environ Microbiol 2: 666–679.

Holmes AJ, Costello A, Lidstrom ME, Murrell JC . (1995). Evidence that participate methane monooxygenase and ammonia monooxygenase may be evolutionarily related. FEMS Microbiol Lett 132: 203–208.

Horz HP, Yimga MT, Liesack W . (2001). Detection of methanotroph diversity on roots of submerged rice plants by molecular retrieval of pmoA, mmoX, mxaF, and 16S rRNA and ribosomal DNA, including pmoA-based terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism profiling. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 4177–4185.

Hutchens E, Radajewski S, Dumont MG, McDonald IR, Murrell JC . (2004). Analysis of methanotrophic bacteria in Movile cave by stable isotope probing. Environ Microbiol 6: 111–120.

Jones CG, Lawton JH, Shachak M . (1994). Organisms as ecosystem engineers. Oïkos 69: 373–386.

Jones HA, Nedwell DB . (1993). Methane emission and methane oxidation in land-fill cover soil. FEMS Microbiol Lett 102: 185–195.

Kightley D, Nedwell DB, Cooper M . (1995). Capacity for methane oxidation in landfill cover soils measured in laboratory-scale soil microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol 61: 592–601.

Kolb S, Knief C, Stubner S, Conrad R . (2003). Quantitative detection of methanotrophs in soil by novel pmoA-targeted real-time PCR assays. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 2423–2429.

Kumar S, Tamura K, Nei M . (2004). MEGA3: Integrated software for molecular evolutionary genetics analysis and sequence alignment. Brief Bioinform 5: 150–163.

Lane DJ . (1991). 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M (eds). Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics. John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, pp 115–175.

Lin JL, Radajewski S, Eshinimaev BT, Trotsenko YA, McDonald IR, Murrell JC . (2004). Molecular diversity of methanotrophs in Transbaikal soda lake sediments and identification of potentially active populations by stable isotope probing. Environ Microbiol 6: 1049–1060.

Lueders T, Wagner B, Claus P, Friedrich MW . (2004). Stable isotope probing of rRNA and DNA reveals a dynamic methylotroph community and trophic interactions with fungi and protozoa in oxic rice field soil. Environ Microbiol 6: 60–72.

Luepromchai E, Singer AC, Yang CH, Crowley DE . (2002). Interactions of earthworms with indigenous and bioaugmented PCB-degrading bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 41: 191–197.

Manefield M, Griffiths R, McNamara NP, Sleep D, Ostle N, Whiteley A . (2007). Insights into the fate of a 13C labelled phenol pulse for stable isotope probing (SIP) experiments. J Microbiol Methods 69: 340–344.

Manefield M, Whiteley AS, Griffiths RI, Bailey MJ . (2002). RNA stable isotope probing, a novel means of linking microbial community function to phylogeny. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 5367–5373.

Molin S, Givskov M . (1999). Application of molecular tools for in situ monitoring of bacterial growth activity. Environ Microbiol 1: 383–391.

Morris SA, Radajewski S, Willison TW, Murrell JC . (2002). Identification of the functionally active methanotroph population in a peat soil microcosm by stable-isotope probing. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 1446–1453.

Mulongoy K, Bedoret A . (1989). Properties of worm casts and surface soils under various plant covers in the humid tropics. Soil Biol Biochem 21: 197–203.

Mummey D, Holben W, Six J, Stahl P . (2006). Spatial stratification of soil bacterial populations in aggregates of diverse soils. Microb Ecol 51: 404–411.

Murrell JC, McDonald IR, Bourne DG . (1998). Molecular methods for the study of methanotroph ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 27: 103–114.

Murrell JC, McDonald IR, Gilbert B . (2000). Regulation of expression of methane monooxygenases by copper ions. Trends Microbiol 8: 221–225.

Muyzer G, de Wall EC, Uitterlinden QG . (1993). Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Envir Microbiol 59: 695–700.

Needham AE . (1957). Components of nitrogenous excreta in the earthworms Lumbricus terrestris, L. and Eisenia foetida (Savigny). J Exp Biol 34: 425–446.

Neufeld JD, Mohn WW, de Lorenzo V . (2006). Composition of microbial communities in hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) contaminated soils from Spain revealed with a habitat-specific microarray. Environ Microbiol 8: 126–140.

Neufeld JD, Vohra J, Dumont MG, Lueders T, Manefield M, Friedrich MW et al. (2007). DNA stable-isotope probing. Nat Protoc 2: 860–866.

Noll M, Matthies D, Frenzel P, Derakshani M, Liesack W . (2005). Succession of bacterial community structure and diversity in a paddy soil oxygen gradient. Environ Microbiol 7: 382–395.

Parkin TB, Berry EC . (1999). Microbial nitrogen transformations in earthworm burrows. Soil Biol Biochem 31: 1765–1771.

Radajewski S, Ineson P, Parekh NR, Murrell JC . (2000). Stable-isotope probing as a tool in microbial ecology. Nature 403: 646–649.

Radajewski S, Webster G, Reay DS, Morris SA, Ineson P, Nedwell DB et al. (2002). Identification of active methylotroph populations in an acidic forest soil by stable-isotope probing. Microbiology 148: 2331–2342.

Reed AJ, Lutz RA, Vetriani C . (2006). Vertical distribution and diversity of bacteria and archaea in sulfide and methane-rich cold seep sediments located at the base of the Florida Escarpment. Extremophiles 10: 199–211.

Reed DW, Fujita Y, Delwiche ME, Blackwelder DB, Sheridan PP, Uchida T et al. (2002). Microbial communities from methane hydrate-bearing deep marine sediments in a forearc basin. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 3759–3770.

Schaefer M, Petersen SO, Filser J . (2005). Effects of Lumbricus terrestris, Allolobophora chlorotica and Eisenia fetida on microbial community dynamics in oil-contaminated soil. Soil Biol Biochem 37: 2065–2076.

Scheutz C, Kjeldsen P . (2004). Environmental factors influencing attenuation of methane and hydrochlorofluorocarbons in landfill cover soils. J Environ Qual 33: 72–79.

Scholten-Koerselman I, Houwaard F, Janssen P, Zehnder AJ . (1986). Bacteroides xylanolyticus sp. nov., a xylanolytic bacterium from methane producing cattle manure. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 52: 543–554.

Singer AC, Jury W, Luepromchai E, Yahng CS, Crowley DE . (2001). Contribution of earthworms to PCB bioremediation. Soil Biol Biochem 33: 765–776.

Spokas K, Bogner J, Chanton JP, Morcet M, Aran C, Graff C et al. (2006). Methane mass balance at three landfill sites: what is the efficiency of capture by gas collection systems? Waste Manag 26: 516–525.

Stralis-Pavese N, Sessitsch A, Weilharter A, Reichenauer T, Riesing J, Csontos J et al. (2004). Optimization of diagnostic microarray for application in analysing landfill methanotroph communities under different plant covers. Environ Microbiol 6: 347–363.

Streese J, Stegmann R . (2003). Microbial oxidation of methane from old landfills in biofilters. Waste Manag 23: 573–580.

Theisen AR, Ali MH, Radajewski S, Dumont MG, Dunfield PF, McDonald IR et al. (2005). Regulation of methane oxidation in the facultative methanotroph Methylocella silvestris BL2. Mol Microbiol 58: 682–692.

Tiunov AV, Dobrovolskaya TG . (2002). Fungal and bacterial communities in Lumbricus terrestris burrow walls: a laboratory experiment. Pedobiologia 46: 595–605.

Uz I, Rasche ME, Towsend T, Ogram AV, Lindner AS . (2003). Characterization of methanogenic and methanotrophic assemblages in landfill samples. Proc R Soc Lond B (Suppl) 270: S202–S205.

Whalen SC, Reeburgh WS, Sandbeck KA . (1990). Rapid methane oxidation in a landfill cover soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 56: 3405–3411.

Whiteley AS, Manefield M, Lueders T . (2006). Unlocking the ‘microbial black box’ using RNA-based stable isotope probing technologies. Curr Opin Biotechnol 17: 67–71.

Wise MG, McArthur JV, Shimkets LJ . (1999). Methanotroph diversity in landfill soil: isolation of novel type I and type II methanotrophs whose presence was suggested by culture-independent 16S ribosomal DNA analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 65: 4887–4897.

Wise MG, McArthur JV, Shimkets LJ . (2001). Methylosarcina fibrata gen. nov., sp. nov. and Methylosarcina quisquiliarum sp.nov., novel type 1 methanotrophs. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 51: 611–621.

Acknowledgements

We thank NERC for funding this work through Grant NE/B505389/1 to IPT, JCM and JIP and Mark Johnson of BIFFA for access to ufton landfill site.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Héry, M., Singer, A., Kumaresan, D. et al. Effect of earthworms on the community structure of active methanotrophic bacteria in a landfill cover soil. ISME J 2, 92–104 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.66

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.66

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Interkingdom interaction: the soil isopod Porcellio scaber stimulates the methane-driven bacterial and fungal interaction

ISME Communications (2023)

-

Soil environment reshapes microbiota of laboratory-maintained Collembola during host development

Environmental Microbiome (2022)

-

Is earthworm a protagonist or an antagonist in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the soil?

International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology (2019)

-

Increased methane concentration alters soil prokaryotic community structure along an artificial pH gradient

Annals of Microbiology (2019)

-

Diversity and metabolic potential of the microbiota associated with a soil arthropod

Scientific Reports (2018)