Abstract

The presence of a large palatal or maxillary defect after partial or total maxillectomy for tumor, trauma or congenital deformation poses a challenge to prosthodontists, particularly when the use of an implant cannot be considered. This case report described the use of an air valve in a hollow silicone obturator to manufacture an inflatable obturator that could be extended further into undercut area to retain itself. The inflatable obturator exhibited adequate retention, stability and border sealing, thereby improving the masticatory, pronunciation and swallowing functions of patients. It may be a suitable alternative treatment option to an implant-retained obturator.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maxillofacial defects are caused by trauma, tumor or congenital deformations. A recent survey showed that oral cancer, which accounts for 2.8% of all malignant tumors in Europe, is the most common cause of maxillofacial defects.1 Moreover, the incidence of oral cancer in China is relatively high compared with the rest of the world.2 Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to the treatment of maxillofacial defects.

Severe deficiencies in appearance, pronunciation and swallowing occur when maxillofacial defects cause oral–nasal transport. These severe malfunctions may ultimately result in psychological problems. Since the 1940s, prosthodontists have tried to help these patients by separating the oral and the nasal cavity using obturator prostheses to improve deglutition, articulation, pronunciation and facial appearance, and in some cases to support the orbital contents to prevent enophthalmos and diplopia.3 The absence of teeth, and the size and configuration of the maxillary defect, may influence the masticatory function of patients wearing an obturator prosthesis4,5 and may lead to a poor rehabilitation outcome. Moreover, the adequate retention of these prostheses is difficult to achieve, especially for large-sized defects.

For many years, prosthodontists have tried different ways to achieve better retention for cases who have undergone extensive maxillectomy. After the development of dental implants, this problem appeared to have been solved. Schmidt et al.6 used zygomatic and standard endosseous implants to retain prostheses in near-total and total maxillectomy patients. Dilek et al.7 reported the case of a partial maxillectomy patient with an obturator that was supported by five mini-dental implants. The author concluded that mini-dental implants can be used when there is a lack of adequate bone tissue for conventional implant placement in the region of the resection. However, for some patients, these implants are not acceptable due to their general health, personal inclination or economic reasons. Finding a way to retain the prosthesis then becomes a problem. Payne and Welton8 designed a latex rubber balloon attached to a denture that was inflated with air to fill the surgical defect, but its clinical usage has not been reported. In the last decade, silicone materials have been widely used to manufacture obturator prostheses. However, there are no published reports regarding the use of inflatable silicone obturators. This article is the first to describe the restoration of maxillary defects with inflatable obturator prostheses based on silicone, which also represented an alternative technique for maxillofacial rehabilitation.

Case reports

Case 1

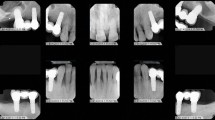

A 20-year-old male patient diagnosed with fibrous dysplasia was referred to the Department of Prosthodontics, Peking University School and Hospital of Stomatology. His chief complaints were deficiencies in speaking and swallowing after extensive resection of the maxilla 3 months previously (Figure 1). The patient had undergone bilateral sub-total maxillectomy, which resected most of the maxillary structures; only a portion of the maxillary tuberosity remained. No surgical reconstruction or any graft for the defect had been applied. Clinical investigation showed an extensive defect of the palatal area and crest ridge, which was classified as a class IV defect according to Aramany's classification. Transport between the oral cavity and the nasal cavity was observed, and the surgical site showed tolerable healing with the formation of a scab and no sign of recrudescence (Figure 2).

As the maxillectomy defect included almost the whole palatal area, the amount of undercut area available to provide retention for a prosthesis was very limited, making adequate retention by traditional methods extremely difficult. However, the use of endosseous implants in pathological bone has not been thoroughly investigated and some commentaries suggest avoiding it for cases of fibrous dysplasia.9 Furthermore, the patient did not want to accept implant therapy for economic reasons. Instead, we suggested an inflatable hollow obturator would be appropriate in this patient.

Sectional maxillary prosthesis, including a complete denture and an inflatable obturator, was used to restore the extensive maxillary defect. The definitive maxillary denture (Luciton 199 denture base material; Dentsply, York, Pennsylvania, USA) was made according to the mandibular dentition with proper occlusion contact. On the intaglio side of the denture, an appropriate undercut that imitated an edentulous ridge contour was made so that the complete denture could be retained afterwards (Figure 3). Then, impression material (Rapid Putty Soft; Coltene/Whaledent, Altstätten, Switzerland) was placed into the intaglio surface of the denture. This material is easy to control and it is not likely to enter deep undercut areas under appropriate pressure. When the impression was made, we ensured that the maxillary denture had a good occlusal contact with the mandibular dentition. The jaw position was guided to the appropriate occlusal vertical dimensions by measuring the distance of the points marked on the patient's face at rest, and was maintained in this position until the impression material had set (Figures 3 and 4). The impression was poured with dental stone (Die-Stone Type III; Heraeus, South Bend, Indiana, USA) to form the working cast, and a one-way air valve (Botou Shengwei Factory, Botou City, Hebei Province, China) was fixed on the palatal surface of the obturator when the obturator prosthesis was made. Odontosil (Dreves, Unna, Germany) silicone material was used to process the hollow silicone obturator prosthesis in the laboratory (Figure 5). The obturator prosthesis and the definitive denture were then trialed by the patient, and an adequate vertical dimension and retention of the prosthesis was demonstrated (Figure 6). When the patient tried the sectional maxillary prosthesis by himself, the compressed obturator was firstly seated in the defect, and the patient could inflate it using a portable air pump (Figure 7) to connect the installed air-valve on the palatal surface of the obturator. When inflated, the obturator was well-fitted with extending evenly into the undercuts. The denture was then seated on the inflated obturator by engaging the suitable undercuts on the palatal surface of the obturator formed during the manufacture of the denture. When the patient wishes to remove the obturator, the compressed air pump is connected directly with the valve to deflate it after the denture is removed.

Sectional maxillary prosthesis including an inflatable obturator and a complete denture for case 1. (a) Palatal view of the obturator showing the air valve (arrow) installed. (b) Lateral view of the sectional prosthesis with the inflatable obturator and complete denture fitting together. The arrows show the cranial side of the obturator.

Case 2

A 68-year-old male complained of deficiencies in speaking, swallowing and mastication after bilateral total maxillectomy 3 months previously (Figure 8). Transport between the nasal cavity and the oral cavity was observed. The remaining mandibular dentition was intact. A hollow inflatable silicone obturator prosthesis combined with a complete denture was prescribed for the patient according to the procedure described above (Figures 9 and 10). When inflated, the obturator was well-fitted and provided adequate support and retention for the complete denture.

Discussion

In case 1, a large palatal defect was evident after surgery for fibrous dysplasia. Oral–nasal transport and the resultant functional deficiencies greatly affected the patient's quality of life. However, the lack of structures to provide retention made it extremely difficult to construct a conventional prosthesis for him. A recent report of the use of endosseous implants has been described in a patient with fibrous dysplasia;9 however, osseointegration in the pathological bone at a microscopic level has not yet been proven. The inflatable hollow obturator prosthesis may be a suitable alternative in patients such as this one who did not want to undergo oral implant treatment for medical and/or economic reasons.

When dealing with extensive defects, the prosthesis requires greater extension into the defect and is therefore heavier. As described in the literature,10 the continuous stress placed on the remaining tissues by a large, heavy obturator jeopardizes their health, compromises the function of the prosthesis and can cause discomfort to the patient. The use of a hollow maxillary obturator may reduce the weight of the prosthesis by up to 33%, depending on the size of the maxillary defect.11 Shaker12 used medical-grade silicone to fabricate the obturator part of the prosthesis with mushroom-like extensions. It was retained by this resilient material which engaged the soft tissue undercuts within the defect. However, the extension into the undercut by this obturator has to be limited, or else its insertion may cause discomfort and bleeding. Our inflatable obturator can be easily placed in undercuts when compressed and extends further when inflated, thereby improving retention without causing obvious discomfort. Compared with the semi-customized balloon-shaped inflatable latex obturator designed by Payne and Welton,8 this new hollow and inflatable obturator is completely customized according to the configuration and size of defects and has been proven clinically. With this advantage, an obturator with the same shape as the defect can extend into the undercut area and engage the undercut more evenly.

The inflatable hollow obturator is lightweight, can be retained well and creates an adequate oral–nasal seal. Deglutition, pronunciation and mastication can be improved and the psychological impact of extensive maxillectomies on patients can therefore be minimized. When faced with patients with microstomia after surgery, an inflatable obturator may also be an alternative option as the obturator can be seated into the oral cavity while deflated and compressed. In cases of extensive maxillectomy in which implants cannot be used, as in the two cases in this report, the inflatable obturator makes prosthetic treatment more acceptable as good retention is achieved by engaging more undercut areas after inflation. In cases of partial maxillectomy, the use of an inflatable obturator may minimize deleterious forces on the remaining structures as further support is gained from surrounding tissues.

Conclusion

Silicone-based inflatable obturators offer a simple technique for the reconstruction of maxillary defects, can be used by most prosthodontists and offer a treatment alternative for patients who may not be able to receive conventional implants. However, the extent to which the inflatable obturator improves pronunciation, deglutition and mastication compared with traditional prostheses, and the long-term serviceability of this prosthesis, requires further investigation.

References

Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E . Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46( 4): 765–781.

Warnakulasuriya S . Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncology 2009; 45( 4/5): 309–316.

Wang RR . Sectional prosthesis for total maxillectomy patients: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 1997; 78( 3): 241–244.

Sato Y, Minagi S, Akagawa Y et al. An evaluation of chewing function of complete denture wearers. J Prosthet Dent 1989; 62( 1): 50–53.

Koyama S, Sasaki K, Inai T et al. Effects of defect configuration, size, and remaining teeth on masticatory function in post-maxillectomy patients. J Oral Rehabil 2005; 32( 9): 635–641.

Schmidt BL, Pogrel MA, Young CW et al. Reconstruction of extensive maxillary defects using zygomaticus implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004; 62 (9 Suppl 2): 82–89.

Dilek OC, Tezulas E, Dincel M . A mini dental implant-supported obturator application in a patient with partial maxillectomy due to tumor: case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 103( 3): e6–e10.

Payne AG, Welton WG . An inflatable obturator for use following maxillectomy. J Prosthet Dent 1965; 15: 759–763.

Bajwa MS, Ethunandan M, Flood TR . Oral rehabilitation with endosseous implants in a patient with fibrous dysplasia (McCune–Albright Syndrome): a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008; 66( 12): 2605–2608.

Wu YL, Schaaf NG . Comparison of weight reduction in different designs of solid and hollow obturator prosthesiss. J Prosthet Dent 1989; 62( 2): 214–217.

Oh WS, Roumanas ED . Optimization of maxillary obturator thickness using a double-processing technique. J Prosthodont 2008; 17( 1): 60–63.

Shaker KT . A simplified technique for construction of an interim obturator for a bilateral total maxillectomy defect. Int J Prosthodont 2000; 13( 2): 166–168.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, YZ., Huang, Z., Ye, HQ. et al. Inflatable hollow obturator prostheses for patients undergoing an extensive maxillectomy: a case report. Int J Oral Sci 4, 114–118 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2012.22

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2012.22