Abstract

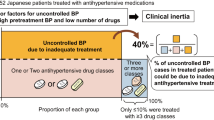

This study aimed to determine the clinical profile, blood pressure (BP) control rates, therapeutic management and physicians’ therapeutic behavior regarding very elderly hypertensive patients. A total of 1540 hypertensive patients ⩾80 years old on antihypertensive therapy and receiving care in primary care settings in Spain were included in this cross-sectional study. The mean patient age was 83.4±3.1 years, 61.9% of patients were women and 49.3% of patients had cardiovascular disease. Of the patients, 27.7% were on monotherapy and 72.3% were on combined therapy (47.4% on two antihypertensive agents and 24.9% on three or more antihypertensive agents). A total of 40.8% (95% confidence interval (CI): 38.4–43.3%) of patients achieved BP goals (<140/90 mm Hg; <130/80 in patients with diabetes, chronic renal disease or cardiovascular disease). Patients with uncontrolled BP were more likely to have metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity, a history of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, renal disease and stroke and were more frequently smokers. Physicians modified the antihypertensive regimens for 27.4% (95% CI: 23.9–30.8%) of the patients with uncontrolled BP, and the addition of another antihypertensive agent was the most frequent modification. With regard to the physicians’ perception of patients’ BP control, the BPs of 44.1% of the patients with uncontrolled BP were considered well controlled by the physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in western countries. One of the main causes of this phenomenon is the continuous aging of the population, leading to an increased frequency of chronic conditions such as hypertension.1, 2 For example, the proportion of hypertensive patients ⩾65 years old increased from ∼48% in 2002 to 58% in 2010 in Spain.3 In addition, three out of four patients ⩾80 years old have hypertension, and high blood pressure (BP) has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in this population.4, 5, 6 Despite this evidence, there is limited information available regarding BP control and the benefits of reducing BP to the recommended target levels in this population.4, 5, 6 In fact, the great majority of clinical trials performed in hypertensive population have excluded very elderly patients or had only small sample sizes.7, 8, 9

The main evidence regarding the benefits of reducing BP levels in very elderly patients comes from the HYVET (Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial) study.10 The HYVET was a clinical trial that included 3845 hypertensive patients ⩾80 years of age. The results demonstrated that decreasing the BP to a level <150/80 mm Hg with antihypertensive treatment significantly reduced the risk of fatal or nonfatal stroke, death from stroke, all-cause mortality, death from cardiovascular causes and the incidence of heart failure.10 However, an excessive reduction of BP to <130 mm Hg systolic may be harmful in the very elderly hypertensive population.11, 12 Despite this evidence, there is still scant information available regarding the clinical profiles, therapeutic management and BP control rates in very elderly patients with hypertension.13, 14, 15

The 2010 PRESCAP (PRESión arterial en la población española en los Centros de Atención Primaria) was a multicenter and cross-sectional survey that aimed to determine BP control rates in hypertensive patients receiving care in primary care settings in Spain.16 This study sought to assess the clinical profiles, BP control rates, therapeutic management approaches and physicians’ therapeutic behavior for very elderly hypertensive patients.

Methods

The design of PRESCAP 2010 has been previously described.3, 16 Briefly, a total of 2635 general practitioners throughout Spain participated in the study, which was conducted over 3 days (8 June 2010–10 June 2010). Each investigator was asked to include up to the first five consecutive outpatients at the clinic who met the inclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ⩾18 years of either sex, (2) an established diagnosis of hypertension and (3) current antihypertensive treatment ongoing for at least 3 months before the trial. Patients with a recent diagnosis of hypertension (<6 months), with the recent initiation of antihypertensive treatment (<3 months) or with secondary hypertension were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain, and before enrollment, the patients gave written informed consent.

The investigators filled out a questionnaire specifically designed for this study using the data from the clinical records for each patient. The biodemographic data (age, sex, body mass index, duration of hypertension and living situation) and cardiovascular risk factors (sedentary life style, dyslipidemia, obesity, diabetes, family history of premature cardiovascular disease, excessive alcohol intake and smoking) were taken from the patient’s clinical records. Cardiovascular risk factors were defined according to the 2007 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines.17 Smoking patients were defined as current smokers who had smoked ⩾1 cigarette per day in the last month. Excessive alcohol intake was considered to be the weekly consumption of equivalent to 26 oz. of 40-proof alcohol. A sedentary lifestyle was defined as a daily physical activity level of less than a 30-min walk.18 Waist circumference was measured at the midway point between the iliac crest and the costal margin. Obesity was defined as a body mass index of ⩾30 kg m−2 and abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference of >102 and >88 cm in men and women, respectively.17

BP measurements were performed according to the 2007 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines, with the patients in a seated position with their backs supported and after a 5-min rest, using calibrated aneroid or mercury sphygmomanometers or validated automatic devices, depending on availability.17 The recorded visit BP was the average of two separate measurements taken by the examining physician. When there was a difference of ⩾5 mm Hg between the two readings, a third measurement was taken. Adequate BP control was defined as a systolic BP <140 mm Hg and a diastolic BP <90 mm Hg (<130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, chronic kidney disease or cardiovascular disease).17 The antihypertensive treatment regimen, including the class, number and time of taking the medication, was also recorded.

Data regarding the target organ damage (left ventricular hypertrophy and carotid disease) were taken from the clinical records for each patient, but no diagnostic technique was specifically performed for this study. Carotid disease was defined as an intima-media thickness >0.9 mm or the presence of plaque. The diagnosis of left ventricular hypertrophy was established by either electrocardiography or echocardiography.17 Data regarding cardiovascular disease (ischemic heart disease, heart failure, renal disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease and advanced retinopathy) were also taken from the patient’s clinical records.

To assess the physicians’ therapeutic behavior regarding BP management, investigators were asked after the BP readings were performed whether they considered their patients to have adequate BP control. The investigators were also asked whether they would recommend any change in antihypertensive treatment and, if so, what change they would make (increasing the dose, the addition of another antihypertensive agent or changing to another antihypertensive agent).

Statistical analysis

Testing for a normal distribution was performed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables were expressed in terms of means and s.d. and categorical variables were expressed as percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test for unpaired data or the Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The data design was subjected to internal consistency rules and ranges to control for inconsistencies/inaccuracies in the collection and tabulation of the data. Statistical significance was set at a P-value<0.05. The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS statistics package, version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Biodemographic data

Overall, 13 420 patients with hypertension were included; a total of 459 patients (3.4%) were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or because incorrect data were recorded. In total, 12 961 patients (mean age 66.3±11.4 years, 52.0% women; mean duration of hypertension 9.1±6.7 years) were analyzed. Of these, 1540 patients (11.88%) were 80 years or older (mean age 83.4±3.1 years; 61.9% women; mean duration of hypertension 13.7±8.4 years).

The clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The presence of other cardiovascular risk factors was very frequent, with the most common being sedentary life style (64.9%; 95% CI: 62.5–67.2%), dyslipidemia (55.2%; 95% CI: 52.7–57.6%) and abdominal obesity (54.9%; 95% CI: 52.4–57.3%). With regard to organ damage, 12.1% (95% CI: 10.4–13.7%) of patients had left ventricular hypertrophy. Nearly half of patients had cardiovascular disease (49.3%; 95% CI: 46.8–51.8%), the most common manifestations being ischemic heart disease (16.7%; 95% CI: 14.8–18.5%) and nephropathy (15.8%; 95% CI: 13.9–17.6%).

Hypertension and BP control rates

The mean BP was 137.0±15.4/75.3±9.7 mm Hg, with significant differences between sexes in both the systolic BP readings (135.3±15.1 in men versus 138.1±15.5 in women; P=0.001) and the diastolic BP readings (74.3±9.8 in men versus 75.8±9.6 mm Hg in women; P=0.004). The distribution of patients according to the different 2007 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology BP categories is presented in Table 2. A total of 40.8% (95% CI: 38.4–43.3%) of patients achieved BP goals, whereas 50.6% (95% CI: 48.1–53.1%) showed control of only systolic BP and 81.9% showed control of only diastolic BP (95% CI: 80.0–83.8%). The total and diastolic BP control rates were similar between men and women, but the systolic BP control rates were significantly higher in men than that in women (Table 3). No significant differences were found in the BP control rates for patients aged 80–84 years compared with those aged 85–89 years or ⩾90 years.

Patients with uncontrolled BP more commonly had metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity, history of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, renal disease and stroke and were more frequently smokers. Moreover, the duration of hypertension was longer in this population (Table 4).

Antihypertensive treatment

The mean time of treatment was 12.4±7.7 years, without significant differences between the sexes. Of the patients, 27.7% were on monotherapy and the other 72.3% were on combined therapy (47.4% on two antihypertensive agents and 24.9% on three or more antihypertensive agents). With regard to each individual antihypertensive agent, 32.6% of the patients were taking angiotensin receptor blockers, 30.4% angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and 18.3% diuretics. Regarding combined therapy, the most frequent combinations prescribed were angiotensin receptor blockers+diuretic (51.7%) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors+diuretic (19.6%) (Table 5). No significant differences were found in the rates of BP control between the groups treated with one, two or three or more antihypertensive agents.

Physicians’ therapeutic behavior regarding BP control

Physicians modified the antihypertensive treatment in 27.4% (95% CI: 23.9–30.8%) of the patients with uncontrolled BP. In 70.9% of the cases, another antihypertensive agent was added; in 27.3% of the cases, the dose of the antihypertensive agent was increased; and in 1.8% of the cases, the medication was exchanged for another agent. The changes in antihypertensive treatment varied according to the systolic BP values. The physicians modified the antihypertensive treatment in 15.0% of patients with systolic BPs ranging between 140 and 149 mm Hg; in 42.1% of those with systolic BPs ranging between 150 and 159 mm Hg; in 50.0% of those with systolic BPs ranging between 160and 169 mm Hg; in 61.1% of those with systolic BPs ranging between 170 and 179 mm Hg; and in 83.3% of those with systolic BPs⩾180 mm Hg (P<0.0001). With regard to the physicians’ perception of patients’ BP control, the BPs of 44.1% of the patients with uncontrolled BP were considered to be well controlled by the physicians. In contrast, 97.1% of patients with good BP control were considered to be well controlled by their physician.

Discussion

Although the most important goal in the hypertensive population should be to decrease the BP to the recommended targets, to actually reduce cardiovascular risk, the treatment of other cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities is essential.17 Therefore, determining the clinical profile of patients with hypertension is necessary. This is particularly true in very elderly subjects, as these patients have specific issues, including altered pharmacokinetics, comorbidities and polypharmacy.19 Our study demonstrated that in very elderly hypertensive patients, the presence of other cardiovascular risk factors was very common, in particular a sedentary lifestyle, dyslipidemia and obesity, in addition to vascular damage (mainly ischemic heart disease and nephropathy). Overall, when compared with previous studies performed in a similar setting, the proportion of patients with comorbidities was greater.15 This greater proportion is mainly because of improved treatment of acute cardiovascular events as well as improved secondary prevention, leading to longer patient survival times.20 This observation implies that the prevalence of very elderly patients with hypertension is progressively increasing. In fact, in Spain this proportion has increased from nearly 9% in 2006 to the 12% currently.15

In recent years, there has been growing interest in assessing the clinical characteristics and proper management of elderly patients with hypertension. However, although the majority of these studies have focused on patients aged 60–65 years old,14, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 only some studies have included very elderly patients.11, 13, 15, 28, 29 In data collected from a community-based cohort study during the 2005 Framingham Heart Study, the prevalence of hypertension, its treatment and its control were compared across age groups. In patients ⩾80 years old, BP control goals were attained in 38% of men and 23% of women.13 In a 2006 study performed in Spain utilizing the same methodology as our study, 923 hypertensive patients ⩾80 years old were included. In that study, despite the fact that 64% of patients were receiving combined antihypertensive therapy, only approximately one-third of the patients attained BP goals.15 In other study performed in Canada in 2008 that included 733 long-term care residents with hypertension (mean age 84 years), of which 566 were receiving antihypertensive medication, 64% achieved BP goals.28 In a 2009 study performed in Spain that included >300 patients aged ⩾80 years, the prevalence of hypertension was 72.8%. Of these patients, almost all were taking antihypertensive drugs (43% on monotherapy and 39.5% taking two agents); 30.7% of patients achieved BP targets.29 In our study, nearly 75% of patients were taking two or more antihypertensive drugs and BP control was achieved in ∼41% of patients. All this evidence indicates that although relevant differences exist in terms of the methodologies and inclusion criteria of these studies and although some studies have found an improvement in BP control rates, the overall rates of BP control were far from optimal. However, it should be noted that in very elderly patients, the optimal target BP is still uncertain.30, 31 In fact, when considering the most recent BP goals as recommended by the European Society of Hypertension (<140/90 mm Hg for the overall hypertensive population), nearly 60% of patients achieved the targets (Table 3).32 In addition, the ACCF/AHA expert consensus guidelines state that systolic BP values of 140–145 mm Hg are acceptable for patients ⩾80 years of age.12

In our study, those patients who did not attain BP goals were more likely to have metabolic syndrome, diabetes, obesity, a history of cardiovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, renal disease and stroke and were more frequently smokers. Other authors have found that the presence of different comorbidities such as diabetes may be associated with worse BP control.15 Therefore, it is more difficult to attain target BP levels in patients with worse control of other cardiovascular risk factors. These data emphasize the need for a global approach to the treatment of hypertensive patients, particularly those at high risk.

With regard to the type of antihypertensive medication, the drugs most frequently prescribed as monotherapy were angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and diuretics. The most commonly prescribed combination regimens were angiotensin receptor blockers+diuretic and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors+diuretic. Previous studies have reported that renin–angiotensin system inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive agents for very elderly patients with hypertension.15, 28 However, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines state that in people aged ⩾80 years old, a calcium-channel blocker is recommended as the first-line therapy, with a thiazide-like diuretic as the second line.33 By contrast, in the HYVET trial, the combination of perindopril and indapamide reduced cardiovascular events in the elderly population.10 It has been reported that the molecular mechanisms underlying hypertension may differ between elderly patients and younger subjects.34 Although this difference may affect the response of elderly patients to antihypertensive medication, the main goal in the management of very elderly patients with hypertension should still be reducing BP levels to recommended targets.

Although physicians modified the antihypertensive treatment regimen more frequently in patients with higher systolic BP values, overall, treatment modifications were made for only 27.4% of patients with uncontrolled BP. The most common modification was the addition of another antihypertensive agent. Therapeutic inertia is frequent in the hypertensive population but is even more frequent in the very elderly population.15 This therapeutic inertia may be related to a false perception of BP control by physicians, as well as the inadequate use of antihypertensive medications, particularly combined therapy, to avoid side effects and polypharmacy in these patients.15, 35 However, evidence shows that high pulse pressure is associated with poorer outcomes in elderly patients. In fact, it has been reported that a diastolic BP⩽60 mm Hg is associated with reduced survival, suggesting that in elderly patients, antihypertensive treatment should not only be based on systolic BP levels.36 This evidence could have had an impact on the management of these patients. Our data showed that patients with poor BP control had higher pulse pressure values than subjects who attained BP targets. However, for patients with poor BP control, the diastolic BP was 78 mm Hg (versus 71 mm Hg for those with good BP control), suggesting that further measures could have been taken to achieve BP targets.

Limitations

The BP control rates were calculated based on two or three office measurements obtained during the same visit. As BP levels change over the time, this methodology may limit the interpretation of the results. However, the high number of patients included may reduce this potential bias. Moreover, the great majority of the studies that have assessed BP control in clinical practice worldwide have used this methodology. However, our study included only patients receiving clinical care from general practitioners in Spain. Therefore, the results of our study can only be generalized to patients receiving clinical care in a similar setting.

Conclusions

Approximately 12% of hypertensive patients receiving care in a primary care setting in Spain are ⩾80 years old. In this population, the presence of other comorbidities is very common. Despite the fact that 72% of these patients are treated with combination antihypertensive therapy, only 4 of 10 patients attain BP targets. General practitioners only modified treatment in 27% of patients with uncontrolled BP. The most common modification was the addition of another antihypertensive agent. The false perception of BP control by physicians may explain at least in part these results.

References

Ezzati M, Hoorn SV, Rodgers A, Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Murray CJ, The Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Estimates of global and regional potential health gains from reducing multiple major risk factors. Lancet 2003; 362: 271–280.

Yach D, Hawkes C, Gould L, Hofman KJ . The global burden of chronic diseases: overcoming impediments to prevention and control. JAMA 2004; 291: 2616–2622.

Llisterri JL, Rodriguez-Roca GC, Escobar C, Alonso-Moreno FJ, Prieto MA, Barrios V, González-Alsina D, Divisón JA, Pallarés V, Beato P . Treatment and blood pressure control in Spain during 2002-2010. J Hypertens 2012; 30: 2425–2431.

Rastas S, Pirttilä T, Viramo P, Verkkoniemi A, Halonen P, Juva K, Niinistö L, Mattila K, Länsimies E, Sulkava R . Association between blood pressure and survival over 9 years in a general population aged 85 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54: 912–918.

Satish S, Freeman DH Jr, Ray L, Goodwin JS . The relationship between blood pressure and mortality in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 367–374.

Gorostidi M, de la Sierra A . Management of hypertension in the very old. Med Clin 2011; 137: 111–112.

SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 1991; 265: 3255–3264.

Dahlöf B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Scherstén B, Ekbom T, Wester PO . Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOPHypertension). Lancet 1991; 338: 1281–1285.

Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, Celis H, Arabidze GG, Birkenhäger WH, Bulpitt CJ, de Leeuw PW, Dollery CT, Fletcher AE, Forette F, Leonetti G, Nachev C, O'Brien ET, Rosenfeld J, Rodicio JL, Tuomilehto J, Zanchetti A . Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension: the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Lancet 1997; 350: 757–764.

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C, Belhani A, Forette F, Rajkumar C, Thijs L, Banya W, Bulpitt CJ, HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 1887–1898.

Badía Farré T, Formiga Pérez F, Almeda Ortega J, Ferrer Feliú A, Rojas Farreras S . Grupo Octabaix. Relationship between blood pressure and mortality at 4 years of follow up in a cohort of individuals aged over 80 years. Med Clin 2011; 137: 97–103.

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, Artinian NT, Bakris G, Brown AS, Ferdinand KC, Ann Forciea M, Frishman WH, Jaigobin C, Kostis JB, Mancia G, Oparil S, Ortiz E, Reisin E, Rich MW, Schocken DD, Weber MA, Wesley DJ . ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 2037–2114.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Evans JC, Levy D . Hypertension in adults across the age spectrum. Current outcomes and control in the community. JAMA 2005; 294: 466–472.

Gu Q, Burt VL, Dillon CF, Yoon S . Trends in antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control among United States adults with. Circulation 2012; 126: 2105–2114.

Rodríguez-Roca GC, Pallarés-Carratalá V, Alonso-Moreno FJ, Escobar-Cervantes C, Barrios V, Llisterri JL, Valls-Roca F, Carrasco-Martín JL, Fernández-Toro JM, Banegas JR, on behalf of the working group of arterial hypertension of the Spanish Society of Primary Care physicians (Group HTA/SEMERGEN) and the PRESCAP 2006 investigators. Blood pressure control and physicians’ therapeutic behavior in a very elderly Spanish hypertensive population. Hypertens Res 2009; 32: 753–758.

Llisterri Caro JL, Rodríguez Roca GC, Alonso Moreno FJ, Prieto Díaz MA, Banegas Banegas JR, Gonzalez-Segura Alsina D, Lou Arnal S, Divisón Garrote JA, Beato Fernández P, Barrios Alonso V . Blood pressure control in hypertensive Spanish population attended in Primary Care setting The PRESCAP 2010 study. Med Clin 2012; 139: 653–661.

Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Narkiewicz K, Ruilope L, Rynkiewicz A, Schmieder RE, Boudier HA, Zanchetti A, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Erdine S, Kiowski W, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Lindholm LH, Viigimaa M, Adamopoulos S, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Bertomeu V, Clement D, Erdine S, Farsang C, Gaita D, Lip G, Mallion JM, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, O'Brien E, Ponikowski P, Redon J, Ruschitzka F, Tamargo J, van Zwieten P, Waeber B, Williams B . 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2007; 25: 1105–1187.

Robledo de Dios T, Ortega Sánchez-Pinilla R, Cabezas Peña C, Forés García D, Nebot Adell M, Córdoba García R . Recommendations on life style. Aten Primaria 2003; 32 (Suppl 2): 30–44.

Sierra C, López-Soto A, Coca A . Hypertension in the elderly population. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2008; 43 (Suppl 2): 53–59.

Wijeysundera HC, Machado M, Farahati F, Wang X, Witteman W, van der Velde G, Tu JV, Lee DS, Goodman SG, Petrella R, O'Flaherty M, Krahn M, Capewell S . Association of temporal trends in risk factors and treatment uptake with coronary heart disease mortality, 1994-2005. JAMA 2010; 303: 1841–1847.

Hammami S, Mehri S, Hajem S, Koubaa N, Frih MA, Kammoun S, Hammami M, Betbout F . Awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among the elderly living in their home in Tunisia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2011; 11: 65.

Gutiérrez-Misis A, Sánchez-Santos MT, Banegas JR, Zunzunegui MV, Castell MV, Otero A . Prevalence and incidence of hypertension in a population cohort of people aged 65 years or older in Spain. J Hypertens 2011; 29: 1863–1870.

Llisterri JL, Barrios V, de la Sierra A, Bertomeu V, Escobar C, González-Segura D . Blood pressure control in hypertensive women aged 65 years or older in a primary care setting. MERICAP study. Rev Esp Cardiol 2011; 64: 654–660.

Llisterri JL, Morillas P, Pallarés V, Fácila L, Sanchís C, Sánchez T . FAPRES researchers. Differences in the degree of control of arterial hypertension according to the measurement procedure of blood pressure in patients ⩾65 years. FAPRES study. Rev Clin Esp 2011; 211: 76–84.

Biskupiak JE, Kim J, Phatak H, Wu D . Prevalence of high-risk cardiovascular conditions and the status of hypertension management among hypertensive adults 65 years and older in the United States: analysis of a primary care electronic medical records database. J Clin Hypertens 2010; 12: 935–944.

Rakugi H, Ogihara T, Goto Y, Ishii M, JATOS Study Group. Comparison of strict- and mild-blood pressure control in elderly hypertensive patients: a per-protocol analysis of JATOS. Hypertens Res 2010; 33: 1124–1128.

Van der Niepen P, Dupont AG . Improved blood pressure control in elderly hypertensive patients: results of the PAPY-65 Survey. Drugs Aging 2010; 27: 573–588.

Tsuyuki RT, McLean DL, McAlister FA . Management of hypertension in elderly long-term care residents. Can J Cardiol 2008; 24: 912–914.

Aguado A, López F, Miravet S, Oriol P, Fuentes MI, Henares B, Badia T, Esteve L, Peligro J . Hypertension in the very old; prevalence, awareness, treatment and control: a cross-sectional population-based study in a Spanish municipality. BMC Geriatr 2009; 9: 16.

Charpentier MM, Bundeff A . Treating hypertension in the very elderly. Ann Pharmacother 2011; 45: 1138–1143.

Aronow WS . Office management of hypertension in older persons. Am J Med 2011; 124: 498–500.

Mancia G, Laurent S, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Burnier M, Caulfield MJ, Cifkova R, Clément D, Coca A, Dominiczak A, Erdine S, Fagard R, Farsang C, Grassi G, Haller H, Heagerty A, Kjeldsen SE, Kiowski W, Mallion JM, Manolis A, Narkiewicz K, Nilsson P, Olsen MH, Rahn KH, Redon J, Rodicio J, Ruilope L, Schmieder RE, Struijker-Boudier HA, van Zwieten PA, Viigimaa M, Zanchetti A . Reappraisal of European guidelines on hypertension management: a European Society of Hypertension Task Force document. J Hypertens 2009; 27: 2121–2158.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Hypertension. The clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. August 2011. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127.

Mateos-Cáceres PJ, Zamorano-León JJ, Rodríguez-Sierra P, Macaya C, López-Farré AJ . New and old mechanisms associated with hypertension in the elderly. Int J Hypertens 2012; 2012: 150107.

Schmieder RE, Ruilope LM . Blood pressure control in patients with comorbidities. J Clin Hypertens 2008; 10: 624–631.

Protogerou AD, Safar ME, Iaria P, Safar H, Le Dudal K, Filipovsky J, Henry O, Ducimetière P, Blacher J . Diastolic blood pressure and mortality in the elderly with cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 2007; 50: 172–180.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express their sincere gratitude to all the investigators who actively participated in this study. Without their dedication and high-quality work, the present publication would not have been possible. We also would like to thank Almirall-Prodesfarma pharmaceuticals for its financial support. All data have been recorded and analyzed independently to prevent bias. The present study was supported by an unrestricted grant provided by Almirall-Prodesfarma pharmaceuticals.

Disclaimer

All data were recorded and analyzed independently to prevent bias.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.G.-A. is a medical doctor of Almirall-Prodesfarma pharmaceuticals, but this affiliation did not influence the recording or management of the data. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ADDENDUM

ADDENDUM

Working group of arterial hypertension of SEMERGEN (Spain). FJ Alonso Moreno (Toledo), LM Artigao Rodenas (Albacete), A Barquilla García (Madroñera, Cáceres), V Barrios Alonso (Madrid), P Beato Fernández (Barcelona), A Calderón Montero (Madrid), JL Cañada Merino (Getxo, Bizkaia), E Carrasco Carrasco (Abarán, Murcia), JL Carrasco Martín (Estepona, Málaga), S Cinza Sanjurjo (Porto do Son, A Coruña), JA Divisón Garrote (Casas Ibáñez, Albacete), R Durá Belinchón (Burjassot, Valencia), C Escobar Cervantes (Madrid), JM Fernández Toro (Cáceres), M Ferreiro Madueño (Sevilla), A Galgo Nafría (Madrid), EI García Criado (Córdoba), A García Lerín (Madrid), L García Matarín (Vícar, Almería), O García Vallejo (Madrid), R Genique Martínez (Amposta, Tarragona), I Gil Gil (Viella, Lleida), A González Sánchez (Lanzarote, Gran Canaria), JL Górriz Teruel (Valencia), S Lou Arnal (Utebo, Zaragoza), JL Llisterri Caro (Valencia), JC Martí Canales (Motril, Granada), JJ Mediavilla Bravo (Burgos), V Pallarés Carratalá (Castellón), J Polo García (Casar de Cáceres, Cáceres), MA Prieto Díaz (Oviedo), T Rama Martínez (Barcelona), GC Rodríguez Roca (La Puebla de Montalbán, Toledo), T Sánchez Ruiz (Valencia), C Santos Altozano (Azuqueca de Henares, Guadalajara), JA Santos Rodríguez (Rianxo, A Coruña), F Valls Roca (Benigànim, Valencia), SM Velilla Zancada (Santander), A Vicente Molinero (Zaragoza), P Panero Hidalgo (Órgiva, Granada).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodriguez-Roca, G., Llisterri, J., Prieto-Diaz, M. et al. Blood pressure control and management of very elderly patients with hypertension in primary care settings in Spain. Hypertens Res 37, 166–171 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.130

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2013.130

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hypertension in older patients, a retrospective cohort study

BMC Geriatrics (2016)

-

Prevalence, prescribing and barriers to effective management of hypertension in older populations: a narrative review

Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice (2015)

-

Comparison of the effects of barnidipine+losartan compared with telmisartan+hydrochlorothiazide on several parameters of insulin sensitivity in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus

Hypertension Research (2015)