Abstract

Masked hypertension has been proven to be associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular diseases. The purpose of this study was to examine the direct associations of obesity-related anthropometric indices, including waist circumference, with masked hypertension. Participants in this population-based survey included 395 residents (⩾35 years) of Ohasama, a rural Japanese community. They measured blood pressure at home (HBP) and underwent an oral glucose-tolerance test. Participants were classified into four groups on the basis of their HBP and casual-screening blood pressure (CBP) values: sustained normotension, white-coat hypertension, masked hypertension or sustained hypertension. The relationships between the obesity-related anthropometric indices and the four blood pressure groups were examined using multivariate analysis adjusted for confounding factors. The mean waist circumference in men was significantly higher in individuals with masked hypertension (87.3 cm) than in those with sustained normotension (81.0 cm) and white-coat hypertension (79.3 cm), whereas the mean waist circumference in women was significantly higher in individuals with sustained hypertension (79.5 cm) than in those with sustained normotension (75.0 cm). In the multivariate analysis, waist circumference, body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio were significantly associated with masked hypertension, particularly in individuals with normal CBP. Our results suggest that HBP measurements might be particularly important in abdominally obese people for the early detection of masked hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is the concurrence of multiple metabolic abnormalities associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD).1, 2 Metabolic syndrome has been reported to be an important risk factor for CVD and mortality,3, 4 and is useful in predicting diabetes mellitus.5

Blood pressure (BP) measurements outside of medical settings, such as self-measured BP at home (HBP), have identified two subgroups of individuals: those with white-coat hypertension,6 who have persistently increased BP levels in a medical setting (referred to as casual-screening BP or CBP) but normal HBP, and individuals with masked hypertension,7, 8 who have normal CBP but increased HBP. Whether white-coat hypertension is a benign condition9, 10 or is linked with an increased risk for target organ damage and a worse prognosis11, 12, 13 is still controversial, but there is a general agreement that individuals with masked hypertension have an increased risk of CVD.7, 8 However, there have been few reports regarding the association between masked hypertension and waist circumference (WC) or metabolic syndrome.

The aim of this study is to investigate whether or not obesity-related anthropometric indices, including WC, BMI and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), are associated with masked hypertension.

Methods

Study population

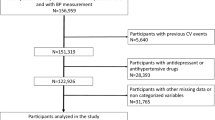

This investigation is a part of a longitudinal observational study of HBP measurements among Ohasama residents since 1987. The socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of this region and complete details of the project are described elsewhere.14, 15, 16 The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tohoku University School of Medicine and by the Department of Health of the Ohasama Town Government. Between 2000 and 2006, we contacted all 4809 individuals aged 35 years or older in four districts of Ohasama town. Those who were not at home during the normal working hours of the study nurses (n=1298) and those hospitalized (n=192) or incapacitated (n=120) were not eligible. Of the remaining 3199 residents, 2181 (68%) provided written, informed consent to participate in the HBP measurement program. We excluded 68 individuals from this analysis as their morning HBP values were the averages of <3 readings (3 days). Of the remaining 2113 individuals, 397 (19%) voluntarily participated in the screening program for diabetes mellitus, including an oral glucose-tolerance test and measurement of WC. Those treated with antidiabetic agents (n=2) were excluded from this analysis. Thus, the total number of participants statistically analyzed was 395. The 395 individuals who participated in the diabetes-screening program were significantly older, had lower systolic HBP levels and comprised a lower proportion of men than those who did not participate (n=1786).

Diabetes screening program

In the screening program for diabetes mellitus, the oral glucose-tolerance test was carried out with a 75-g glucose-equivalent carbohydrate load (Trelan G; Ajinomoto Pharma Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) after the fasting blood samples had been taken. WC was measured at the umbilical level by trained public-health nurses. Individuals were asked to breathe out gently at the time of the measurement, and the tape was held firmly in a horizontal position. Hip circumference was measured over the widest part of the gluteal region. WHR was calculated as WC in centimeters divided by hip circumference in centimeters.

Blood pressure measurements

HBP was measured using the semi-automatic HEM-747IC-N (Omron Healthcare Co., Ltd, Kyoto, Japan), a device based on the cuff-oscillometric method that generates a digital display of both systolic and diastolic BP values.17 Physicians and public health nurses instructed the participants on how to use the device and record HBP results. The participants then measured their own BP once in the morning, in the sitting position within 1 h after awaking, and after ⩾2 min of rest and recorded such measurements for 4 weeks. Those on antihypertensive drugs measured their BP before taking medication. Although many participants measured their HBP twice or more per occasion, we used the first value from each measurement in our analysis to exclude individual selection bias.18 HBP was defined as the mean of all measurements.

The CBP measurements were taken twice consecutively using an automatic device (HEM-907, Omron Healthcare Co. Ltd.) in the morning before the oral glucose-tolerance test after at least 2 min of rest. The average of two consecutive readings from each individual was used as CBP.

The HBP and CBP measuring devices used in this study have been validated17, 19 and meet the criteria established by the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.20

Categorization of participants according to blood pressure

Participants were classified into four groups on the basis of their HBP and CBP values: sustained normotension (CBP: systolic BP<140 mm Hg and diastolic BP<90 mm Hg; HBP: systolic BP<135 mm Hg and diastolic BP<85 mm Hg); white-coat hypertension (CBP: systolic BP⩾140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP⩾90 mm Hg; HBP: systolic BP<135 mm Hg and diastolic BP<85 mm Hg); masked hypertension (CBP: systolic BP<140 mm Hg and diastolic BP<90 mm Hg; HBP: systolic BP⩾135 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP⩾85 mm Hg); and sustained hypertension (CBP: systolic BP⩾140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP⩾90 mm Hg; HBP: systolic BP⩾135 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP⩾85 mm Hg). The cut-off values were derived from several guidelines.21, 22, 23 In this analysis, those with sustained normotension included untreated individuals with sustained normotension and treated individuals with controlled sustained normotension. The white-coat hypertension group included treated individuals with uncontrolled BP only when this was measured in the medical setting. Similarly, the masked hypertension group included those with ‘masked uncontrolled hypertension,’ which would represent uncontrolled BP ‘masked’ by the use of CBP measurement alone. These concepts are consistent with those used in earlier studies7, 8 and are based on earlier reports showing that an insufficient duration of action for antihypertensive drugs represents an important factor in causing higher HBP or ambulatory BP values compared with CBP.24 As reported earlier, the prevalence of masked hypertension was significantly higher among men than among women (25% in men, 12% in women, P<0.01), whereas that of white coat hypertension was significantly higher among women than among men (11 and 19% in men and women, respectively, P=0.04).14

Statistical analysis

The homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the following formula: HOMA-IR=fasting plasma-glucose (mg per 100 ml) × fasting plasma-insulin (μg per 100 ml)/405. Metabolic risk factors, obesity-related anthropometric indices and other characteristics among the four groups were compared using analysis of variance or Fisher's exact test. Analysis of covariance was used to adjust for between-group differences in obesity-related anthropometric indices. The odds ratios (ORs) for masked hypertension were examined using the logistic regression model. The following anthropometric criteria were used for the analysis: WC, criteria of the Japanese metabolic syndrome,25 International Diabetes Federation metabolic syndrome26 or Ohasama;14 BMI, criteria of the Japan Society for the Study of Obesity;27 and WHR, criteria of the World Health Organization.28

All data are expressed as mean±s.d. unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was established at P<0.05 (two-tailed). All statistical calculations were carried out using the SAS system (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The characteristics of participants classified under the four groups are shown in Table 1. Those with sustained hypertension were significantly older than those with sustained normotension. The mean HOMA-IR was significantly higher in individuals with sustained hypertension (1.92±2.67) than in those with sustained normotension (1.21±0.78).

Table 2 shows the means of obesity-related anthropometric indices among the four hypertensive subgroups. The mean WC, BMI and WHR were significantly higher in individuals with masked hypertension and sustained hypertension than in those with sustained normotension. The mean WC in men was significantly higher in individuals with masked hypertension (87.3±9.9) than in those with sustained normotension (81.0±7.9) and those with white-coat hypertension (79.3±6.2), whereas the mean WC in women was significantly higher in individuals with sustained hypertension (79.5±8.5) than in those with sustained normotension (75.0±8.5). The mean BMI in men was significantly higher in individuals with masked hypertension (25.5±3.2) than in those with sustained normotension (23.1±3.0) and those with white-coat hypertension (21.8±1.9), whereas the mean BMI in women was significantly higher in individuals with sustained hypertension (24.7±3.3) and those with white-coat hypertension (24.3±3.0) than in those with sustained normotension (22.7±2.9). The mean WHR in each sex did not differ significantly among the four groups. Similar results were obtained after adjustment of these anthropometric indices by confounding factors (data not shown).

Table 3 shows the adjusted ORs per certain-value increase in obesity-related anthropometric indices for the presence of masked hypertension. Higher WC, BMI and WHR were significantly associated with masked hypertension, especially in individuals with normal CBP. An analysis of these findings classified by sex indicated that the association was stronger in men than in women. The interactions between sex and anthropometric indices were significant in BMI (P=0.02 for model 1, and P=0.004 for model 2), whereas no significant interaction was observed in WC and in WHR (all P>0.05).

The ORs for the presence of masked hypertension related to criteria reported earlier for metabolic syndrome or obesity are shown in Table 4. Out of five anthropometric criteria examined (that is, criteria from five groups), the prevalence of masked hypertension was most likely to be present in individuals who met the Japanese Metabolic Syndrome criteria (that is, men with a WC⩾85 cm and women with a WC⩾90 cm). Further analyses classified by sex indicated that the ORs related to each criterion in men were substantially larger than those in women, although with wider 95% confidence intervals (data not shown).

Discussion

We found that individuals with masked hypertension or sustained hypertension had significantly higher WC than individuals with sustained normotension. Increases in obesity-related anthropometric indices such as WC, BMI or WHR were associated with masked hypertension. The ORs of Japanese metabolic syndrome criteria for WC and the International Diabetes Federation metabolic syndrome criteria for WC for the presence of masked hypertension were higher than those of the other criteria.

There were sex-specific associations of WC and BMI with masked hypertension. Mean WC and BMI in men were significantly higher in individuals with masked hypertension compared with those with sustained normotension, suggesting that men with high WC or BMI should measure their HBP to diagnose masked hypertension. The higher prevalence of masked hypertension in men than in women also supports the importance of HBP measurement in detection of masked hypertension in men. Meanwhile, high WC and high BMI in women were not significantly associated with masked hypertension; high BMI in women was significantly associated with white-coat hypertension and sustained hypertension. Women with high BMI should also measure their own HBP, as Ugajin et al.12 reported that white-coat hypertension was a transitional condition to sustained hypertension and suggested that white-coat hypertension carries a poor cardiovascular prognosis. However, the number of participants in this study was relatively small which resulted in wider 95% confidence intervals classified by sex. The generally lesser values of ORs in women than those in men suggest that an impact of WC or other anthropometric indices for masked hypertension might vary between sexes; further studies with larger number of participants should be needed.

Smoking habit was approximately threefold higher in masked hypertension as compared with sustained normotension or white-coat hypertension. Smoking was an independent predictor of the magnitude of the difference between CBP and HBP in our earlier study.29 The lower BP observed in smokers is suggested to be only a transient decline in the BP as a result of abstinence from a short-time ‘off smoking’ before the measurement of BP.30 Accordingly, the smoker might show a comparably high BP in the daily measurement at home. Mikkelsen et al.31 also showed that smoking seems to diminish the screening daytime difference. Physicians might need to pay special attention to smoking habits in individuals to avoid their masked hypertension, as well as to reduce their CVD risks directly.

The anthropometric indices that would be most applicable to the detection of masked hypertension remain uncertain. In a meta-regression analysis of prospective studies, de Koning et al.32 reported that WHR and WC were significantly associated with the risk of CVD events, although they could not determine which indices had a stronger predictive power. Vazquez et al.5 also reported that BMI, WC and WHR had consistently strong associations with the incidence of diabetes, but did not determine the priority of these indices. Further research is needed to clarify which anthropometric index would be the most applicable to diagnose masked hypertension.

In 2005, eight Japanese scientific associations collaborated to define metabolic syndrome for the Japanese population;25 however, many arguments remain, particularly in terms of the higher cutoff value of WC for women than for men.33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 In this study, WC cutoff values of the Japanese metabolic syndrome criteria (⩾85 cm in men, ⩾90 cm in women) had the highest detective power for masked hypertension among five anthropometric indices used. We had earlier proposed optimal cutoff values of WC (⩾87 cm in men, ⩾80 cm in women; Ohasama criteria for WC) for a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome by receiver operating characteristic analysis.14 In the earlier report, we used a lower HBP cutoff point (systolic ⩾125 mm Hg or diastolic ⩾80 mm Hg) compared with this study that represents hypertension on the basis of HBP (systolic ⩾135 mm Hg or diastolic ⩾85 mm Hg). Furthermore, the number of selected individuals using the Japanese metabolic syndrome criteria (n=19) was lower than that using the Ohasama criteria (n=61); accordingly, comparably high-risk individuals were selected using the Japanese metabolic syndrome criteria, resulting in a discrepancy between the two studies. Although masked hypertension and metabolic syndrome are different disease states, further prospective studies are needed to investigate the appropriate criteria of WC to identify high-risk patients.

This study showed a close association of masked hypertension with high WC as well as high BMI, which are important risk factors for metabolic syndrome. We had earlier reported that elevated HBP levels were significantly associated with a clustering of metabolic risk factors.14 HBP has a stronger predictive power for CVD mortality and morbidity than CBP.16, 39, 40 HBP values improve the accuracy of screening for hypertension and for assessing BP control during treatment, and encourage drug compliance.40 Although CBP-based metabolic syndrome is useful for detecting CVD risk,3, 4, 5 it is reasonable to assume that risk assessment on the basis of HBP might be a more effective tool than that based on CBP.

The study cohort was significantly older, had lower systolic HBP levels and comprised a lower proportion of men than non-participants. Those with sufficient time and health concerns might have been more likely to voluntarily participate. Moreover, diabetes is screened on weekdays, which might lead to a lower proportion of men participating. We included age and gender in the logistic regression models as major confounding factors. However, the possibility of selection bias needs to be considered when generalizing the present findings.

In conclusion, men with high WC or BMI should measure their HBP to detect masked hypertension and women with high BMI should also measure their HBP to predict future sustained hypertension. Furthermore, early-stage, non-pharmacologic intervention, such as lifestyle modification, might be useful for these individuals. HBP measurements should be taken in abdominally obese people because of their high probability of masked or sustained hypertension.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Grundy SM, Brewer Jr HB, Cleeman JI, Smith Jr SC, Lenfant C . Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation 2004; 109: 433–438.

Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsen B, Lahti K, Nissen M, Taskinen MR, Groop L . Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 683–689.

Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J . Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 2006; 119: 812–819.

Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, Erwin PJ, Gami LA, Somers VK, Montori VM . Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49: 403–414.

Vazquez G, Duval S, Jacobs Jr DR, Silventoinen K . Comparison of body mass index, waist circumference, and waist/hip ratio in predicting incident diabetes: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Rev 2007; 29: 115–128.

Pickering TG, James GD, Boddie C, Harshfield GA, Blank S, Laragh JH . How common is white coat hypertension? JAMA 1988; 259: 225–228.

Bobrie G, Chatellier G, Genes N, Clerson P, Vaur L, Vaisse B, Menard J, Mallion JM . Cardiovascular prognosis of ‘masked hypertension’ detected by blood pressure self-measurement in elderly treated hypertensive patients. JAMA 2004; 291: 1342–1349.

Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Asayama K, Obara T, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Hoshi H, Satoh H, Imai Y . Prognosis of ‘masked’ hypertension and ‘white-coat’ hypertension detected by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring 10-year follow-up from the Ohasama study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46: 508–515.

Kario K, Shimada K, Schwartz JE, Matsuo T, Hoshide S, Pickering TG . Silent and clinically overt stroke in older Japanese subjects with white-coat and sustained hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38: 238–245.

Khattar RS, Senior R, Lahiri A . Cardiovascular outcome in white-coat versus sustained mild hypertension: a 10-year follow-up study. Circulation 1998; 98: 1892–1897.

Palatini P, Mormino P, Santonastaso M, Mos L, Dal Follo M, Zanata G, Pessina AC . Target-organ damage in stage I hypertensive subjects with white coat and sustained hypertension: results from the HARVEST study. Hypertension 1998; 31: 57–63.

Ugajin T, Hozawa A, Ohkubo T, Asayama K, Kikuya M, Obara T, Metoki H, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Satoh H, Tsuji I, Imai Y . White-coat hypertension as a risk factor for the development of home hypertension: the Ohasama study. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 1541–1546.

Verdecchia P, Reboldi GP, Angeli F, Schillaci G, Schwartz JE, Pickering TG, Imai Y, Ohkubo T, Kario K . Short- and long-term incidence of stroke in white-coat hypertension. Hypertension 2005; 45: 203–208.

Sato A, Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Obara T, Metoki H, Inoue R, Hara A, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Satoh H, Oka Y, Imai Y . Optimal cutoff point of waist circumference and use of home blood pressure as a definition of metabolic syndrome: the Ohasama study. Am J Hypertens 2008; 21: 514–520.

Imai Y, Satoh H, Nagai K, Sakuma M, Sakuma H, Minami N, Munakata M, Hashimoto J, Yamagishi T, Watanabe N . Characteristics of a community-based distribution of home blood pressure in Ohasama in northern Japan. J Hypertens 1993; 11: 1441–1449.

Ohkubo T . Prognostic significance of variability in ambulatory and home blood pressure from the Ohasama study. J Epidemiol 2007; 17: 109–113.

Imai Y, Abe K, Sasaki S, Minami N, Munakata M, Sakuma H, Hashimoto J, Sekino H, Imai K, Yoshinaga K . Clinical evaluation of semiautomatic and automatic devices for home blood pressure measurement: comparison between cuff-oscillometric and microphone methods. J Hypertens 1989; 7: 983–990.

Imai Y, Otsuka K, Kawano Y, Shimada K, Hayashi H, Tochikubo O, Miyakawa M, Fukiyama K . Japanese society of hypertension (JSH) guidelines for self-monitoring of blood pressure at home. Hypertens Res 2003; 26: 771–782.

Imai Y, Nishiyama A, Sekino M, Aihara A, Kikuya M, Ohkubo T, Matsubara M, Hozawa A, Tsuji I, Ito S, Satoh H, Nagai K, Hisamichi S . Characteristics of blood pressure measured at home in the morning and in the evening: the Ohasama study. J Hypertens 1999; 17: 889–898.

Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation. American National Standards for Electronic or Automated Sphygmomanometers. AAMI Analysis and Review: Washington, DC, 1987.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo Jr JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright Jr JT, Roccella EJ . The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289: 2560–2572.

European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension–European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2003; 21: 1011–1053.

Verdecchia P, Staessen JA, White WB, Imai Y, O’Brien ET . Properly defining white coat hypertension. Eur Heart J 2002; 23: 106–109.

Chonan K, Hashimoto J, Ohkubo T, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Kikuya M, Hozawa A, Matsubara M, Suzuki M, Fujiwara T, Araki T, Satoh H, Hisamichi S, Imai Y . Insufficient duration of action of antihypertensive drugs mediates high blood pressure in the morning in hypertensive population: the Ohasama study. Clin Exp Hypertens 2002; 24: 261–275.

Matsuzawa Y . Metabolic syndrome—definition and diagnostic criteria in Japan. J Atheroscler Thromb 2005; 12: 301.

The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/IDF_Meta_def_final.pdf. 2006.

Examination Committee of Criteria for ‘Obesity Disease’ in Japan; Japan Society for the Study of Obesity. New criteria for ‘obesity disease’ in Japan. Circ J 2002; 66: 987–992.

World Health Organization. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1: Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999 WHO/NCD/NCS/99.2 1999.

Hozawa A, Ohkubo T, Nagai K, Kikuya M, Matsubara M, Tsuji I, Ito S, Satoh H, Hisamichi S, Imai Y . Factors affecting the difference between screening and home blood pressure measurements: the Ohasama Study. J Hypertens 2001; 19: 13–19.

Mann SJ, James GD, Wang RS, Pickering TG . Elevation of ambulatory systolic blood pressure in hypertensive smokers. A case-control study. JAMA 1991; 265: 2226–2228.

Mikkelsen KL, Wiinberg N, Hoegholm A, Christensen HR, Bang LE, Nielsen PE, Svendsen TL, Kampmann JP, Madsen NH, Bentzon MW . Smoking related to 24-h ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate: a study in 352 normotensive Danish subjects. Am J Hypertens 1997; 10: 483–491.

de Koning L, Merchant AT, Pogue J, Anand SS . Waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular events: meta-regression analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 850–856.

Eguchi M, Tsuchihashi K, Saitoh S, Odawara Y, Hirano T, Nakata T, Miura T, Ura N, Hareyama M, Shimamoto K . Visceral obesity in Japanese patients with metabolic syndrome: reappraisal of diagnostic criteria by CT scan. Hypertens Res 2007; 30: 315–323.

Hara K, Matsushita Y, Horikoshi M, Yoshiike N, Yokoyama T, Tanaka H, Kadowaki T . A proposal for the cutoff point of waist circumference for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in the Japanese population. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1123–1124.

Miyawaki T, Hirata M, Moriyama K, Sasaki Y, Aono H, Saito N, Nakao K . Metabolic syndrome in Japanese diagnosed with visceral fat measurement by computed tomography. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2005; 81: 471–479.

Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Asayama K, Imai Y . A proposal for the cutoff point of waist circumference for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in the Japanese population. Diabetes Care 2006; 29: 1986–1987.

Oizumi T, Daimon M, Wada K, Jimbu Y, Kameda W, Susa S, Yamaguchi H, Ohnuma H, Kato T . A proposal for the cutoff point of waist circumference for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome in the Japanese population. Circ J 2006; 70: 1663.

Shiwaku K, Anuurad E, Enkhmaa B, Nogi A, Kitajima K, Yamasaki M, Yoneyama T, Oyunsuren T, Yamane Y . Predictive values of anthropometric measurements for multiple metabolic disorders in Asian populations. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005; 69: 52–62.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Metoki H, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Satoh H, Imai Y . Prediction of stroke by self-measurement of blood pressure at home versus casual screening blood pressure measurement in relation to the Joint National Committee 7 classification: the Ohasama study. Stroke 2004; 35: 2356–2361.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, Obara T, Metoki H, Inoue R, Hara A, Hirose T, Hoshi H, Hashimoto J, Totsune K, Satoh H, Imai Y . Prediction of stroke by home ‘morning’ versus ‘evening’ blood pressure values: the Ohasama study. Hypertension 2006; 48: 737–743.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Ohasama public health nurses and technicians, as well as the secretarial staff of our laboratory. This study was supported in part by Grants for Scientific Research (15790293, 16590433, 17790381, 18390192, 18590587, 19590929 and 19790423) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan; Grant-in-Aid (H17-Kenkou-007, H18-Junkankitou[Seishuu]-Ippan-012 and H20-Junkankitou[Seishuu]-Ippan-009, 013) from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants, Japan; Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) fellows (16.54041, 18.54042, 19.7152, 20.7198, 20.7477 and 20.54043); Health Science Research Grants and Medical Technology Evaluation Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan; Japan Atherosclerosis Prevention Fund; Uehara Memorial Foundation; Takeda Medical Research Foundation; National Cardiovascular Research Grants; and Biomedical Innovation Grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Asayama, K., Sato, A., Ohkubo, T. et al. The association between masked hypertension and waist circumference as an obesity-related anthropometric index for metabolic syndrome: the Ohasama study. Hypertens Res 32, 438–443 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.37

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.37

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The prevalence of masked hypertension and masked uncontrolled hypertension in relation to overweight and obesity in a nationwide registry in China

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

The eighth installment in Asian perspectives, salt, pregnancy, and masked hypertension

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Masked hypertension and its associated cardiovascular risk in young individuals: the African-PREDICT study

Hypertension Research (2016)

-

Metabolic risk factors and masked hypertension in the general population: the Finn-Home study

Journal of Human Hypertension (2014)

-

Use of Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring to Guide Hypertensive Therapy

Current Treatment Options in Cardiovascular Medicine (2013)