Abstract

In this paper, we present a two-locus model of selection for an autotetraploid population. We also investigate a measure of disequilibrium that occurs between homologous chromosomes in the diploid gametes of autotetraploids, namely chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. We apply the model and measure of disequilibrium to compare how an adaptive epistatic gene combination is inherited and selected for in an autotetraploid versus diploid population. Autotetraploids are expected to have higher genomic mutation and recombination rates relative to diploids, due to a greater ploidy level. These two processes can work in opposition in terms of selection for adaptive epistatic gene combinations. While a higher genomic mutation rate can generate the alleles that confer an epistatic combination more quickly, a higher recombination rate is expected to break the combination down more quickly. We show that chromosomal gametic disequilibrium in autotetraploids can potentially compensate for less linkage disequilibrium in autotetraploids. We also explore how double reduction affects the inheritance of and selection for an epistatic gene combination. Over all, our analysis provides theoretical evidence that adaptive epistatic combinations can be selected for more efficiently in autotetraploids versus diploids. This may provide insight into empirical work that finds epistasis has a role in causing population differentiation between autotetraploid plant populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polyploidy is widespread taxonomically, occurring in protists, plants, fungi and animals (cf. Lewis, 1980; Otto and Whitton, 2000). It is particularly abundant in angiosperms, in which ~75% of monocot and eudicot species have established polyploid populations, in whole or in part (Husband et al., 2013). Moreover, many crop species are polyploid (Leitch and Leitch, 2008) and of autopolyploid or allopolyploid origin (Paterson, 2005). Polyploidy is less widespread in animals, although there are exceptions in some taxa. For example, the fish family Salmonidae had an autotetraploid origin (Allendorf and Thorgaard, 1984) and tetrasomic inheritance persists in the diverse set of extant species within this family (Phillips and Rab, 2001). In amphibians and reptiles, a polyploid species or variety is typically paired with a diploid species and there are no distinct polyploid taxonomic genera and families (Bogart, 1980). Given the occurrence of polyploidy in nature and agricultural crops, it is desirable to understand its conseque93 for both inheritance and the process of natural selection.

Gaps in our understanding of selection in polyploids

Although important advances have been made in our understanding of inheritance and selection within polyploid populations, important gaps remain (Otto and Whitton, 2000). For example, population genetic models of selection in polyploids have thus far been largely limited to a single locus, with models comparing the response to selection in polyploids versus diploids (Haldane, 1926; Wright, 1938; Hill, 1971; Otto and Whitton, 2000), the effect of panmictic gametic disequilibrium (explained below) on the response to selection (Rowe, 1982; Rowe and Hill, 1984) and comparing mutational load in polyploids versus diploids (Butruille and Boiteux, 2000; Otto and Whitton, 2000). An exception is the recent work of Selmecki et al. (2015) that simulated an infinite sites model of mutation in a clonal tetraploid and assumed additive fitness effects of mutations. An earlier exception is Ronfort (1999) who modeled multilocus mutational load in a tetraploid assuming independence of the load across loci. The models of Ronfort (1999) and Selmecki et al. (2015) therefore represent extremes in terms of inheritance, assuming either independent segregation of alleles among loci or clonality, and additive fitness under log or linear scaling, respectively.

The lack of a general multilocus selection model for polyploids is problematic. For example, a recent study of the natural autotetraploid plant species Campanulastrum americanum (Etterson et al., 2007) and an earlier study of the autotetraploid agricultural crop alfalfa (Medicago sativa, Bingham et al., 1994) suggest that epistasis may be a factor in subpopulation differentiation and inbreeding depression, respectively. Epistasis occurs when alleles at two or more loci interact to produce a phenotype. Accordingly, a conceptual and theoretical framework of inheritance and selection that involves two or more loci is needed to aid our understanding of natural and artificial selection processes in these autotetraploid species. Furthermore, even in the absence of epistasis, selection at one locus can affect allele frequencies at another locus due to a statistical correlation in allele frequencies, where this statistical correlation can arise through several processes including random genetic drift, physical linkage and/or non-independent segregation of chromosomes. Polyploidy is expected to increase the recombination rate relative to diploids (Sved, 1964; Pecinka et al., 2011), which may in turn affect the multilocus selection process. In this paper, we derived a two-locus model of selection for an autotetraploid population.

Models of autotetraploid meiosis

Although a study of two-locus selection is lacking in autotetraploids, a great deal of effort has been put into modeling autotetraploid meiosis, including multilocus models (reviewed in Bever and Felber [1992] and Gallais [2003]). Autotetraploid meiosis is unique relative to diploid meiosis in that in addition to bivalent chromosome pairing, tetravalent pairing is also possible. Tetravalent pairing was recognized as occurring since the work of de Winton and Haldane (1931), but it was not until recently that it was modeled (Sybenga, 1994; Wu et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2004; Wu and Ma, 2005; Lu et al., 2012; Voorrips and Maliepaard, 2012; Rehmsmeier, 2013). In particular, Rehmsmeier (2013) derived a mathematically tractable two-locus model of autotetraploid meiosis that incorporates tetravalents and paired-partner switching. Paired-partner switching occurs when a chromosome aligns and recombines with different homologous chromosomes, which can lead to double reduction. Double reduction occurs when genomic regions of sister chromatids segregate into the same gamete. An advantage of Rehmsmeier's model is that the rate of double reduction is a property of underlying rates of tetravalent formation, recombination and paired-partner switching, whereas other models (Wu et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2004; Wu and Ma, 2005; Lu et al., 2012) treat recombination rates and double reduction as independent parameters. Recombination and double reduction are actually correlated, such that double reduction is a function of rates of tetravalent formation, recombination and paired-partner switching. The Voorrips and Maliepaard (2012) model is a more accurate model of meiosis than Rehmsmeier's in that it not only includes tetravalent formation and paired-partner switching, but also models recombination at the level of chiasma and includes chiasma interference and partial-preferential pairing of chromosomes (Sybenga, 1994). Although the Voorrips and Maliepaard (2012) model is more accurate, we use Rehmsmeier's (2013) model of meiosis, leaving the consequences of chiasma formation and partial-preferential pairing for future study.

Adaptive epistatic gene combinations

The analysis of our two-locus model of selection focuses on the evolution of adaptive epistatic gene combinations. An adaptive epistatic gene combination is a set of alleles from two or more loci that when put together in a genotype generate an adaptive phenotype. One mechanism of subpopulation differentiation is the evolution of adaptive epistatic gene combinations in local subpopulations. Such a mechanism may explain hybrid breakdown under greenhouse conditions in F1 crosses between subpopulations of C. americanum (Etterson et al., 2007). Adaptive epistatic combinations have been reported in descendants of hybrids between species of sunflower (Rieseberg et al., 1996). Adaptive epistatic gene combinations therefore occur in nature and form a hypothesis for subpopulation differentiation and it is of interest to understand their evolution in autotetraploids.

Otto and Whitton (2000) noted that an increase in the recombination rate in autopolyploids could negatively affect the evolution of gene combinations because recombination would disassociate these combinations. Nevertheless, as noted by Otto and Whitton (2000), the genomic mutation rate is higher in autopolyploids. A higher mutation rate may increase the rate at which epistatic gene combinations are formed. Together, the increase in recombination and mutation rates may be conflicting processes in autopolyploids with respect to the evolution of adaptive epistatic gene combinations.

The opportunity for direct inheritance of an epistatic gene combination from parent to offspring is different between diploids and autotetraploids. When the loci occur on the same chromosome, a diploid parent can only pass the combination to its offspring on a single chromosome, whereas an autotetraploid parent can pass the combination at both the chromosome and gamete levels. At the gamete level in an autotetraploid, an epistatic combination may occur across two homologous chromosomes, with one allele on one chromosome and the other allele on the other chromosome. During the course of adaptation it is not known whether inheritance of an epistatic gene combination is typically at the chromosome level or gamete level, nor is it known whether inheritance at the gamete level can compensate for higher recombination rates in autotetraploids.

Linkage and chromosomal gametic disequilibria

In autotetraploids, there is the potential for both linkage disequilibrium between allelic states across two loci on a single chromosome and an association between the states of homologous chromosomes that together form a diploid gamete, which we refer to as chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. Chromosomal gametic disequilibrium indicates an association between the states of homologous chromosomes across multiple loci in a gamete. It is distinct from gametic disequilibrium, which is often used synonymously with linkage disequilibrium and involves an association between allelic states across loci. It is also distinct from ‘ panmictic gametic disequilibrium’, which in the context of polyploids indicates an association between the allelic states in a gamete at a single locus (Gallais, 2003). Lastly, it is distinct from ‘gametic association of two non-homologous genes’ (sensu Gallais, 2003) because this measure of association is at the level of the genotype of a gamete and ignores the haplotypes of chromosomes that make up a gamete. Furthermore, gametic association of two non-homologous genes measures disequilibrium relative to what is expected if allelic states both within and between loci were independent in a gamete. In the methods we present a measure of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium and show that it is independent of linkage disequilibrium in an Appendix 4. Together, linkage disequilibrium and chromosomal gametic disequilibrium provide independent measures of genome level associations within autotetraploids. In the context of the evolution of adaptive epistatic gene combinations, a comparison of linkage disequilibrium with chromosomal gametic disequilibrium gives insight into whether adaptive epistatic gene combinations are typically inherited at the chromosome level or gamete level during the course of adaptation.

Double reduction

Unlike diploids, double reduction can occur in autotetraploids during meiosis with tetravalent pairing and when there is a recombination event between the centromere and a genomic region, recombinant chromosomes cosegregate during Anaphase 1 and then sister genomic regions cosegregate during Anaphase 2. Double reduction has consequences at the population level. Double reduction can slow the rate of decay in linkage disequilibrium between two loci (Bennett, 1954; Crow, 1954; Gallais, 2003). This is because a tetraploid zygote that is formed in part by a gamete with two sister chromatid regions is less likely to generate unique recombinant products during meiosis since these ancestrally sister chromatid regions are identical in sequence. A reduction in the rate of decline in linkage disequilibrium may be of importance for the evolution of adaptive epistatic gene combinations since adaptation requires the simultaneous occurrence of the alleles that together form the epistatic combination. At a single locus, double reduction tends to increase the level of homozygosity within tetraploid zygotes. Increased homozygosity by double reduction may allow for more effective selection against deleterious alleles (Butruille and Boiteux, 2000). More efficient selection against deleterious alleles with double reduction may be important in the context of epistatic selection if the alleles that confer the adaptation are deleterious when alone in a genotype, as occurs in the model in this paper.

Outline of this study

In this paper, we present a mathematical model of two-locus selection in an autotetraploid population. We focus on a single randomly mating population and investigate selection of an adaptive epistatic gene combination in an autotetraploid population and compare this to a diploid population. In the model, two alleles—one from each locus—when placed together in a genotype confer an adaptive epistatic gene combination. If either of these alleles are alone in a genotype then the fitness of the genotype is reduced relative to the wildtype genotype that lacks both alleles. This type of epistasis is expected to generate hybrid breakdown in both autotetraploid and diploid populations under greenhouse conditions in a manner similar to that observed in C. americanum (Etterson et al., 2007). We derive expectations for chromosomal gametic disequilibrium and show how it is independent from linkage disequilibrium. We then investigate selection of an adaptive epistatic combination in autotetraploids, using a diploid population as a basis of comparison, and accounting for rates of mutation and recombination, dosage effects, double reduction and chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. The investigation of selection gives insight into whether adaptive epistatic gene combinations are expected to be more common in autotetraploids versus diploids.

Materials and Methods

We investigate a two-locus model with two alleles at each locus. Locus A has alleles A1 and A2 and locus B has alleles B1 and B2. Loci A and B occur on the same chromosome arm with the A locus proximal to the centromere. We assume alleles A2 and B2 together form an adaptive gene combination, but if these alleles occur alone in a genotype then they are deleterious relative to a genotype homozygous for the A1 and B1 alleles. We study inheritance and selection in both a diploid and autotetraploid population.

Modes of gamete formation and meiotic transition functions

Diploid

Fisher (1947) derived a model of meiosis in terms of ‘modes of gamete formation’. Under this approach, a diploid genotype at two loci is represented as a1b1/a2b2, where a and b indicate the two loci and a1b1 the alleles at these loci on the first homologous chromosome and a2b2 the alleles at these loci on the second homologous chromosome. a1 and a2 could be identical in state, the subscripts simply indicate the homologous chromosome the allele occurs on prior to meiosis, likewise for the b locus. There are two modes of gamete formation: aibi and aibj for i ≠ j and i, j∈{1,2}. Mode aibi indicates that a gamete has the same alleles as in one of the parental chromosomes. Mode aibj indicates a gamete has an allele from one of the parental chromosomes at one of the loci and an allele from the other parental chromosome at the other locus. Mode aibi occurs with probability (1−r)2+2r(1−r)/2 and mode aibj with probability 2r(1−r)/2+r2. In these equations, r is the effective rate of recombination between loci (see Table 1 for parameter definitions).

Gamete modes and their associate probabilities can be used to define a meiotic transition function that gives the probability a genotype passes a particular gamete to an offspring. In our model, we also include the process of mutation during meiosis. Mutation occurs during chromosome duplication and during the repair process associated with recombination. From a modeling perspective we are interested in whether an allelic state mutates to a different state during the entire meiotic process. An efficient approach to modeling this is to invoke mutation at the gamete level and ask whether during the meiotic process an allele in a gamete mutated to a different state with probability μ.

Define fij→k to give the probability that a genotype that is a combination of gametes i and j generates gamete k following the gamete modes model and mk→ℓ to give the probability that mutation during the meiotic process caused a gamete that otherwise would have been in state k to transition to state ℓ. Values for fij→k are calculated by taking a genotype that is a combination of gametes i and j, generating all possible gametes and their probabilities of formation according to the gamete mode model and then summing the probabilities associated with gamete k. Values for mk→ℓ are calculated by counting the number of shared and unshared allelic states between two gametes. μ is raised to the power of unshared states and (1−μ) is raised to the power of shared states. Together, the probability of a genotype that is a combination of gametes i and j passing a gamete in state ℓ to an offspring is  , where the sum is overall possible gametic states k. Specific values for fij→k and mk→ℓ are most easily presented in matrix form and are provided in Appendix 1.

, where the sum is overall possible gametic states k. Specific values for fij→k and mk→ℓ are most easily presented in matrix form and are provided in Appendix 1.

Tetraploid

As noted by Fisher (1947), there are eleven modes of gamete formation for an autotetraploid genotype represented as a1b1/a2b2/a3b3/a4b4. Following the ordering of Rehmsmeier (2013), these modes are (1) aibi/aibi, (2) aibj/aibj, (3) aibi/aibj, (4) aibj/aibk, (5) aibi/ajbi, (6) aibj/akbj, (7) aibi/ajbj, (8) aibi/ajbk, (9) aibj/ajbi, (10) aibj/ajbk and (11) aibj/akbℓ for i≠j≠k≠ℓ and i,j,k,ℓ∈{1,2,3,4}. Rehmsmeier (2013) derived a five-parameter model of gamete formation: q is the effective recombination rate between the centromere and locus A, r is the effective recombination rate between locus A and locus B, pPC is the probability of a paired-partner switch between the centromere and locus A, pDP is the probability of a paired-partner switch between the A and B loci and τ is the probability of tetravalent formation. In the context of paired-partner switching, adjustment of recombination rates is necessary to account for potentially two effective recombination events with  the probability of an effective recombination event on each side of a switch location in the region between the centromere and locus A, respectively. Likewise,

the probability of an effective recombination event on each side of a switch location in the region between the centromere and locus A, respectively. Likewise,  the corresponding probability of an effective recombination event on each side of a switch location in the region between locus A and locus B, respectively. Our paper focuses on the case when there is potentially one paired-partner switch and Appendix 2 provides the probability of each gamete mode for this case, where these probabilities come directly from Rehmsmeier (2013). Inspection of formulas in Appendix 2 verifies that paired-partner switching only occurs when τ>0. As derived by Rehmsmeier (2013), the coefficient of double reduction at locus A is

the corresponding probability of an effective recombination event on each side of a switch location in the region between locus A and locus B, respectively. Our paper focuses on the case when there is potentially one paired-partner switch and Appendix 2 provides the probability of each gamete mode for this case, where these probabilities come directly from Rehmsmeier (2013). Inspection of formulas in Appendix 2 verifies that paired-partner switching only occurs when τ>0. As derived by Rehmsmeier (2013), the coefficient of double reduction at locus A is  and at locus B is

and at locus B is  . Our analysis focuses on the case when τ=2/3, which is the expected probability of quadrivalent formation when there is no tendency toward bivalency versus tetravalency (Rehmsmeier, 2013).

. Our analysis focuses on the case when τ=2/3, which is the expected probability of quadrivalent formation when there is no tendency toward bivalency versus tetravalency (Rehmsmeier, 2013).

Similar to the diploid case, gamete modes and their associated probabilities can be used to define an autotetraploid meiotic transition function that gives the probability that a genotype passes a particular gamete to an offspring. As with the diploid case, we include the process of mutation during meiosis and invoke mutation at the gamete level asking whether during the meiotic process an allele in a gamete mutated to a different state with probability μ. Since there is redundancy in our enumeration of gametes, transition probabilities mk→ℓ need to account for this. For example, the gamete A1B1/A1B1 can mutate to gamete A1B1/A1B2 in two ways by either the first or the second B1 allele mutating to B2 (see Appendix 3). Together, the probability of a genotype that is a combination of gametes i and j passing a gamete in state ℓ to an offspring is  , where the sum is overall possible gametic states k. Note that while the general form of the autotetraploid meiotic transition function is the same as the diploid, specific values for fij→k and mk→ℓ are different from the diploid case and provided in Appendix 3.

, where the sum is overall possible gametic states k. Note that while the general form of the autotetraploid meiotic transition function is the same as the diploid, specific values for fij→k and mk→ℓ are different from the diploid case and provided in Appendix 3.

As a theoretical control, we also model an autotetraploid population that assumes there is no chromosomal gametic disequilibrium (see below). In this model of inheritance, parents undergo meiosis as described above, but chromosomes within a gamete are disassociated from each other to form a population-level haploid gamete pool. Offspring are formed by randomly drawing four gametes from this pool with replacement. Under this model, linkage disequilibrium is sustained, but chromosomal gametic disequilibrium is disassociated.

Disequilibrium measures

Linkage disequilibrium

Linkage disequilibrium is an association between the states of alleles at two loci within a chromosome. The standard measure of two-locus linkage disequilibrium is  , where pAiBj is the frequency of the haplotype AiBj at the population level. In the context of autotetraploid population genetics, it is worth noting that

, where pAiBj is the frequency of the haplotype AiBj at the population level. In the context of autotetraploid population genetics, it is worth noting that  or the determinant of the matrix of haplotype frequencies with elements

or the determinant of the matrix of haplotype frequencies with elements  for i,j∈{1,2}. Furthermore, it is worth noting that D also measures the deviation between the frequency of a haplotype and its expected frequency assuming independent inheritance, such that

for i,j∈{1,2}. Furthermore, it is worth noting that D also measures the deviation between the frequency of a haplotype and its expected frequency assuming independent inheritance, such that  for all i,j∈{1,2}.

for all i,j∈{1,2}.

Chromosomal gametic disequilibrium

In autotetraploid populations (as well as a general tetraploid population), there is potentially an additional level of disequilibrium at the gamete level, which is an association between the states of two homologous chromosomes in a diploid gamete. An over all measure of this disequilibrium ( ) is the determinant of a matrix with elements

) is the determinant of a matrix with elements  for i, j,k,ℓ ∈{1,2} and where

for i, j,k,ℓ ∈{1,2} and where  is the frequency of a gamete with AiBj the state of one homologous chromosome and AkBℓ the other homologous chromosome, that is

is the frequency of a gamete with AiBj the state of one homologous chromosome and AkBℓ the other homologous chromosome, that is

At the individual gamete level a measure of association is the difference between the observed value of  and its expected value assuming no association between chromosomes that make up a gamete, or

and its expected value assuming no association between chromosomes that make up a gamete, or

Unlike linkage disequilibrium, values of  are not expected to be equal in absolute value for all i, j, k and ℓ and in Appendix 4 we show that there are six independent

are not expected to be equal in absolute value for all i, j, k and ℓ and in Appendix 4 we show that there are six independent  that contribute to

that contribute to  . Furthermore, we show that observed values of

. Furthermore, we show that observed values of  decompose into the effect due to linkage and the effect due to non-independence among chromosomes that make up a gamete.

decompose into the effect due to linkage and the effect due to non-independence among chromosomes that make up a gamete.

Selection

We assume a discrete non-overlapping generation model and random mating. We model the frequency of gametes immediately after meiosis and before the formation of zygotes, such that the frequency of the ℓth gamete is xℓ. The fitness of a genotype that is the combination of gametes i and j is wij and we assume that wij=wji. Mean fitness of a population is  , where the sum is overall possible i, j combinations. The frequency of the ℓth gamete in the next generation

, where the sum is overall possible i, j combinations. The frequency of the ℓth gamete in the next generation  is

is

where this sum is over all possible i, j, k combinations. This formula is general for both diploids and autotetraploids, but with different sets of gametes between the two cases and correspondingly different values for fij→k, mk→ℓ and  .

.

We assume that fitness follows a dose-response like function. Baseline fitness is given by the genotype homozygous for the A1 and B1 alleles. Fitnesses of other genotypes are a function of the frequency (dosage) of the A2 and B2 alleles in a genotype. In particular, the fitness of the epistatic combination is proportional to the product of dosages of the A2 and B2 alleles (Figure 1). This model of epistatic fitness is motivated by biochemical processes where the rate of synthesis of a beneficial product is a function of the simultaneous presence of two enzymes. When either of the A2 and B2 alleles are absent, then fitness is reduced relative to the genotype homozygous for the A1 and B1 alleles (Supplementary Figure 1). This reduction in fitness could be due to wasted resources in generating the product of an allele that has no serviceable function in absence of another allele, or the allele being free to interact in a negative manner with alleles at other loci because it is not tied-up with its epistatic partner. The nature of the fitness function is quite general and allows for fitnesses that are marginally concave up, S-shaped, weakly concave down and concave down in shape.

The model of the fitness of genotypes, including adaptive epistatic gene combinations. When A2 and B2 alleles occur together in a genotype they form an adaptive epistatic gene combination. Fitness is a function of the frequencies of A2 and B2 alleles in a genotype. Four surfaces are presented that encapsulate the range of possible fitness surfaces. (a) The fitness surface for the epistatic gene combination is concave down. Here a genotype has 50% of maximum fitness when the frequencies of the A2 and B2 alleles are both 1/4 in the genotype. Parameter values are α=2.5, β=5.73. (b) A more weakly concave-down surface. Here a genotype has 50% of maximum fitness when the frequencies of the A2 and B2 alleles are both 1/2 in the genotype. Parameter values are α=1.55, β=2.85. (c) An S-shaped surface in which a genotype has 50% of maximum fitness when the frequencies of the A2 and B2 alleles are both 1/2 in the genotype. Parameter values are α=20, β=0.00678. (d) A concave-up surface in which a genotype has 50% of maximum fitness when the frequencies of the A2 and B2 alleles are both 3/4 in the genotype. Parameter values are α=1.25, β=0.177. For all surfaces, parameters determining the strength of selection are κ1=κ2=0.001, λ1=λ2=0.5, ξ1=ξ2 =−0.01 and γ=0.1.

More specifically, there is a set of parameters λℓ and κℓ for ℓ∈{1,2} which govern the shape of the fitness function when either alleles A2 (ℓ=1) or B2 (ℓ=2) occurs by themselves in a genotype. When the epistatic combination is present, there is a set of parameters α and β which govern the shape of the fitness function as the product of the A2 and B2 allele frequencies increases. In the function, xij and yij are the frequencies of the A2 and B2 alleles, respectively, in the genotype composed of gametes i and j. Parameters ξℓ for ℓ∈{1,2} determine the over all strength of selection against alleles A2 (ℓ=1) or B2 (ℓ=2) when they occur by themselves in a genotype. Parameter γ determines the over all strength of selection for the epistatic combination consisting of A2 and B2 alleles. With these parameters and variables in mind, the fitness of a genotype consisting of gametes i and j is

When xijyij=0, either the A2 or B2 allele or both alleles are absent in a genotype and the adaptive epistatic gene combination does not exist. We assume that ξℓ<0, λℓ>0 and κℓ>0, such that fitness declines relative to the baseline genotype when xijyij=0. When xijyij>0, both the A2 or B2 alleles are present in a genotype and the adaptive epistatic gene combination exists for γ>0, β>0 and α>0. In the fitness function Ci are normalizing constants, such that at  ,

,  and

and  . With these normalizing constants, fitness equals 1+ξ1, 1+ξ2 and 1+γ when xij=1 and yij=0, xij=0 and yij=1, and xij=1 and yij=1, respectively. When xijyij=0 the decline in fitness with an increase in the dosage of the A2 or B2 allele can be linear and act additively (Supplementary Figure 1a) or concave down and act recessively (Supplementary Figure 1b). It can also be S-shaped and concave up, which would reflect dominance (not shown). Our analysis focuses on the concave down and linear models of deleterious effects because these models are consistent with the average dominance properties of deleterious mutations (Simmons and Crow, 1977; Agrawal and Whitlock, 2011). When xijyij>0, the increase in fitness can be marginally concave down (Figure 1a), weakly concave down (Figure 1b), S-shaped (Figure 1c) and concave up (Figure 1d). We study the consequences of all of these types of fitness surfaces. The difference between the concave down and weakly concave down fitness surfaces in our study is that in the concave-down surface fitness reaches 50% of its maximum when xij=yij=1/4, whereas in the weakly concave-down surface, fitness reaches 25% of its maximum when xij=yij=1/4. In the S-shaped surface, fitness reaches 50% of its maximum when xij=yij=1/2, but only weakly increases until that point. In the concave-up surface, fitness reaches 50% of its maximum when xij=yij=3/4; thus, selection is very weak except when the frequency of the epistatic combination is high in a genotype.

. With these normalizing constants, fitness equals 1+ξ1, 1+ξ2 and 1+γ when xij=1 and yij=0, xij=0 and yij=1, and xij=1 and yij=1, respectively. When xijyij=0 the decline in fitness with an increase in the dosage of the A2 or B2 allele can be linear and act additively (Supplementary Figure 1a) or concave down and act recessively (Supplementary Figure 1b). It can also be S-shaped and concave up, which would reflect dominance (not shown). Our analysis focuses on the concave down and linear models of deleterious effects because these models are consistent with the average dominance properties of deleterious mutations (Simmons and Crow, 1977; Agrawal and Whitlock, 2011). When xijyij>0, the increase in fitness can be marginally concave down (Figure 1a), weakly concave down (Figure 1b), S-shaped (Figure 1c) and concave up (Figure 1d). We study the consequences of all of these types of fitness surfaces. The difference between the concave down and weakly concave down fitness surfaces in our study is that in the concave-down surface fitness reaches 50% of its maximum when xij=yij=1/4, whereas in the weakly concave-down surface, fitness reaches 25% of its maximum when xij=yij=1/4. In the S-shaped surface, fitness reaches 50% of its maximum when xij=yij=1/2, but only weakly increases until that point. In the concave-up surface, fitness reaches 50% of its maximum when xij=yij=3/4; thus, selection is very weak except when the frequency of the epistatic combination is high in a genotype.

The fitness function for wij assumes the population is in an environment where the epistatic combination of the A2 and B2 alleles confers an adaptive benefit. Under greenhouse conditions and in the context of the Etterson et al. (2007) paper, this adaptive benefit is lost and genotypes with mixtures of A1, B1, A2 and B2 alleles would have fitnesses less than the baseline genotype homozygous for the A1 and B1 alleles.

In this paper, we focus attention on adaptation in an environment in which the epistatic combination of the A2 and B2 alleles confers an adaptive benefit. We are interested in whether there are conditions in which the epistatic combination reaches high frequency in autotetraploids, but remains absent or at low frequency in diploids. This finding would be consistent with epistasis having an enhanced role in adaptation in autotetraploids versus diploids under these conditions.

In our analysis, populations are initially fixed for the A1 and B1 alleles. Mutation then generates alleles A2 and B2 through the transition function mk→ℓ. The process of selection either increases the frequency of alleles A2 and B2, or is unable to do so and these alleles remain at low frequency.

Results

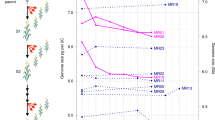

Figure 2 provides an example of selection conditions in which the epistatic combination establishes more efficiently in an autotetraploid versus a diploid population. The efficiency of selection was measured as the number of generations it takes mean fitness of a population, initially fixed for the A1 and B1 alleles, to reach 90% of the maximum possible fitness, which corresponds to the fitness of the genotype homozygous for both the A2 and B2 alleles. Figure 2 assumes additive deleterious effects, concave-down epistatic fitness (see Model section, Figure 1) and strengths of selection equal to ξ1=ξ2=−0.01 for deleterious effects and γ=0.1 for the epistatic combination. Beyond a recombination rate of 0.05 in diploids, a population does not reach 90% of maximum possible fitness (at 0.05 increments in r from a baseline of zero), and correspondingly the epistatic combination does not reach high frequency. In contrast, the epistatic combination reaches high frequency and 90% of maximum fitness across all recombination rates in autotetraploids. Furthermore, for moderate to high recombination rates, chromosomal gametic disequilibrium allows for more efficient selection of the epistatic combination, provided that there is limited double reduction (black circles).

Comparison of the rate of selection between diploids and autotetraploids. The figure plots the number of generations for mean fitness of a population to reach 90% of maximum possible fitness as a function of recombination rate for a diploid population (squares), an autotetraploid population that assumes the diploid gamete pool model without double reduction (black circles) and with double reduction (gray circles), and an autotetraploid population that assumes the haploid gamete pool model without double reduction (black triangles) and with double reduction (gray triangles). In the diploid gamete pool model chromosomal gametic disequilibrium may occur, and in the haploid gamete pool model chromosomal gametic disequilibrium does not occur (see Materials and Methods). For a given recombination rate circular and triangular points are staggered to avoid overlap. There are no points plotted for the diploid population beyond a recombination rate of 1/20 because the population did not reach 90% of the maximum possible fitness within 50 000 generations. For the autotetraploid population it is assumed that the recombination rate between the centromere and locus A (q) and between locus A and locus B (r) are the same. Fitness follows the concave-down parameter set for the adaptive epistatic combination (part [a] of Figure 1) and the additive deleterious model (part [a] of Supplementary Figure 1). Selection parameters are ξ1=ξ2 =− 0.01 and γ=0.1. The mutation rate at the allelic level is μ=10−5. Without double reduction the remaining parameters are τ=2/3, pPC=0 and pDP=0. With double reduction the remaining parameters are τ=2/3, pPC=1/3 and pDP=1/3.

Under the conditions in Figure 2, higher recombination rates do not have a negative effect on selection for the epistatic combination in autotetraploids when there is both chromosomal gametic disequilibrium and when chromosomal gametic disequilibrium is absent. Interestingly, chromosomal gametic disequilibrium marginally improved selection efficiency when double reduction was limited, but reduced efficiency when double reduction was present. Inspection of linkage disequilibrium and specific chromosomal gametic disequilibrium values gives insight as to why. With a high rate of recombination and in the absence of double reduction, the gamete A1B2/A2B1 has a disequilibrium value that is greater than the level of linkage disequilibrium (Figure 3a). With a high rate of recombination and in the presence of double reduction, gametes A1B2/A2B2, A2B1/A2B2 and A2B2/A2B2 have levels of disequilibrium slightly less than the level of linkage for the A2B2 chromosome, but then the level of disequilibrium of the A2B2/A2B2 becomes very large up until the epistatic combination nears high frequency (Figure 3b). Note the difference in scale between parts (a) and (b) of Figure 3. When chromosomal gametic disequilibrium is forced to be zero, linkage disequilibrium is not affected and remains similar to cases with chromosomal gametic disequilibrium (Figure 3c). Marginally more efficient selection with chromosomal gametic disequilibrium and positive disequilibrium for the A1B2/A2B1 gamete with limited double reduction is consistent with the hypothesis that an autotetraploid population can make use of the epistatic combination occurring at the gamete level. Less efficient selection with chromosomal gametic disequilibrium and double reduction indicates that these conditions are less favorable with respect to selection for epistatic combinations. Under these conditions, it is more likely that a genotype formed by an A1B2/A2B1 gamete generates a gamete that does not have both A2 and B2 alleles because of double reduction, which is consistent with the A1B2/A2B1 gamete being in negative disequilibrium. Gametes A1B2/A2B2, A2B1/A2B2 and A2B2/A2B2 are in positive disequilibrium, but these involve A2B2 chromosomes, which take a long time to reach high frequency.

Linkage disequilibrium and chromosomal gametic disequilibrium as a function of the frequency of the A2 allele during the course of selection of the epistatic gene combination. Selection parameters, mutation rate and meiotic parameters are the same as in Figure 2, with the recombination rate equal to 0.5. Part (a) corresponds to an autotetraploid population that is not experiencing double reduction, (b) an autotetraploid population that is experiencing double reduction and (c) an autotetraploid population that conforms to the gamete pool model in which chromosomal gametic disequilibrium is not possible. Gray curve—linkage disequilibrium. Black curve—disequilibrium of A1B2/A2B1 gamete. Long-dashed curve—disequilibrium of A1B1/A2B2 gamete. Dot-dashed—disequilibrium of A1B2/A2B2 gamete. Short-dashed—disequilibrium of A2B2/A2B2 gamete.

Figure 2 indicates that an autotetraploid population can select for an epistatic combination more efficiently than a diploid population, yet chromosomal gametic disequilibrium is not required for better selective efficiency. So, what is a necessary condition for better efficiency in autotetraploid? A simple explanation is to recognize that alleles A2 and B2 had additive deleterious effects when alone in a genotype in Figure 2, such that the deleterious dosage effect of allele A2 or B2 was greater in diploids versus tetraploids. Accordingly, early in the evolution of the epistatic combination and when genotypes with one copy of the A2 or B2 allele, but not both, are common there is stronger selection against these genotypes in diploids versus tetraploids. Making the deleterious effects of the A2 and B2 alleles more recessive results in improved efficiency of selection for both diploids and autotetraploids, but the autotetraploid continues to be more efficient for the degree of recessivity that is modeled (Table 2).

Results summarized in Figure 2 and Table 2 assumed fairly strong selection for the epistatic combination (10%). With weaker selection for the epistatic combination (and weaker deleterious effects of alleles A2 and B2 when alone in a genotype), selection for the epistatic combination in autotetraploids can still be more efficient than diploids with recessive deleterious effects and the concave-down model of beneficial epistatic effects (Table 3). But, for the weakly concave-down, S-shaped and concave-up fitness models, selection for the epistatic combination in autotetraploids is less efficient than diploids with weak selection and recessive deleterious effects (Table 3). Diploids incur proportionally larger dosage effects than autotetraploids, such that recessivity causes a proportionally larger reduction in the deleterious effects of the A2 and B2 alleles when alone in a genotype in diploids versus autotetraploids. A larger reduction in the deleterious effects in diploids versus autotetraploids allows for more efficient selection for the epistatic combination in diploids because the A2 and B2 alleles can increase in frequency faster when they are at low frequency. Under the additive deleterious model and weak selection, more efficient selection switches back to the autotetraploid population (Table 4).

Lastly, we examine the effect of mutation rate. An increase in the mutation rate may allow for the epistatic combination to reach high frequency because it may generate chromosomes, gametes and genotypes with both the A2 and B2 alleles more quickly. For example, if the mutation rate is increased by a factor of 10 under the selection conditions of Figure 2, the combination evolves to high frequency in both diploids and autotetraploids across all recombination rates (Table 5), whereas with the lower mutation rate in Figure 2 the epistatic combination did not reach high frequency in the diploid population for moderate to high recombination rates. Nevertheless, under these conditions mean fitness and correspondingly the frequency of the epistatic combination reach high values sooner in autotetraploids versus diploids for moderate to high recombination rates.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that adaptive epistatic gene combinations can be selected for more efficiently in autotetraploids versus diploids provided that epistasis is sufficiently strong, such that there is an immediate gain in fitness when a genotype consists of both alleles that make up the adaptive epistatic combination. These findings support the possibility that positive selection may be an underlying cause of the epistatic basis of subpopulation differentiation in the plant species C. americanum (Etterson et al., 2007).

The effect of recombination

Interestingly, the adaptive epistatic combination evolved more efficiently in autotetraploids versus diploids when recombination rates were higher versus lower. Sved (1964) noted that autotetraploids are expected to have a higher genomic rate of recombination than diploids and there is empirical support for higher recombination rates in tetraploids compared to diploids in Arabidopsis (Pecinka et al., 2011). Otto and Whitton (2000) made the conjecture that an increase in the genomic rate of recombination in polyploids could inhibit selection for gene combinations due to the breakdown of linkage between alleles. Inspection of Figure 2 and Tables 2, 3 (with concave-down epistasis), 4 and 5 indicate that provided that the recombination rate is not too small, doubling the recombination rate in autotetraploids (up to a value of 0.5) relative to a diploid results in better or similar rates of selection for the epistatic combination in an autotetraploid versus diploid population. Although autotetraploids are a priori expected to have a higher recombination rate than diploids, recombination rates are evolvable and Yant et al. (2013) found a reduction in the cross-over rate after genome duplication in Arabidopsis arenosa. Our results suggest that when adaptation is mediated by epistatic gene combinations, evolution toward lower recombination rates may have a negative effect on autotetraploids relative to diploids.

The effect of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium

Our model and analysis indicates that chromosomal gametic disequilibrium can potentially compensate for the breakdown of linkage disequilibrium between epistatic alleles by recombination. In the absence of double reduction, the gamete A1B2/A2B1, which carries the epistatic combination is in positive chromosomal gametic disequilibrium in autotetraploids. Double reduction results in a switch from A1B2/A2B1 being in positive disequilibrium to gametes A1B2/A2B2, A2B1/A2B2 and A2B2/A2B2 being in positive chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. This switch is interesting in itself and consistent with the double reduction process. Initially, gametes that carry the epistatic combination are expected to be A1B2/A2B1 gametes. Double reduction increases the probability that a parent that inherited this gamete will not pass this gamete to an offspring because double reduction results in A1B2/A1B2 and A2B1/A2B1 gametes, which results in a negative disequilibrium value for the A1B2/A2B1 gamete. These gametes no longer carry the epistatic combination, which results in less efficient selection. It is not until the A2 and B2 alleles reach higher frequency that selection can take hold of the epistatic combination in A1B2/A2B2, A2B1/A2B2 and A2B2/A2B2 gametes. In the haploid gamete pool model, the effect of double reduction is reduced because chromosomes in gametes are disassociated from each other when forming the pool of gametes. Accordingly, double reduction has less of an effect on the rate of establishment of the epistatic combination.

Empirically it may be promising to genotype gametes in autotetraploids and measure chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. Our results indicate that we would expect different types of chromosomal gametic disequilibria as the rate of double reduction varies. Furthermore, our results indicate that chromosomal gametic disequilibria may compensate for higher rates of genomic recombination in autotetraploids versus diploids and it would be interesting to compare linkage disequilibrium to chromosomal gametic disequilibrium in nature and during the course of artificial selection.

A comparison with selection at a single locus

At a single locus, polyploidy can increase a population's response to selection relative to diploids provided that the dominance level in polyploids is sufficiently high relative to diploids (Otto and Whitton, 2000) or that panmictic gametic disequilibrium is in the direction of adaptive alleles at a locus (Rowe, 1982; Rowe and Hill, 1984). These principles have parallels in the case of two-locus selection and epistasis. The concave down fitness surfaces with epistasis correspond to the hyperbolic model of fitness in Otto and Whitton (2000) and it is for these types of surfaces that an autotetraploid population responds to selection better relative to diploids at both a single locus and two loci. Recessivity of deleterious alleles sometimes results in more efficient selection of an adaptive epistatic combination in the autotetraploid versus diploid population. Nevertheless, recessivity can result in no distinguishable difference in the efficiency of selection or poorer efficiency in autotetraploids versus diploids. Linkage disequilibria and chromosomal gametic disequilibria in the direction of the epistatic combination allow for a better response to selection in autotetraploids versus diploids, which is similar to the effect of panmictic gametic disequilibria at a single locus.

Otto and Whitton (2000) also noted that because deleterious alleles tend to be more masked in polyploids versus diploids, they are expected to segregate at higher frequency and be more abundant in polyploids versus diploids. If there is a change in environment that causes combinations of these previously deleterious alleles to become adaptive in an epistatic manner, then the combination may have a head-start in autotetraploids compared to diploids because of higher initial allele frequencies. Autotetraploids may then respond to selection more rapidly than diploids. Our analysis did not investigate this possibility and assumed populations were fixed for the A1 and B1 alleles initially. There may be an expansion of parameter space in which an autotetraploid responds to selection more efficiently compared to diploids if the initial conditions are at deleterious mutation-selection balance and there is a subsequent change in environment.

Incorporating chiasma formation, partial-preferential pairing and other processes

Our selection model used Rehmsmeier's (2013) model of meiosis which allows for a mechanistic understanding of how paired-partner switches and recombination contribute to double reduction. Yet, recombination rates are effective rates in the model and it would be helpful to model recombination at the level of chiasma, as is done in Voorrips and Maliepaard (2012). Modeling recombination at the level of chiasma will help clarify how much higher effective recombination rates are expected to be in autotetraploids compared to diploids. In addition, it is not yet clear the extent to which the rate of paired-partner switches is affected by the pattern of chiasma formation, nor do we have a complete theoretical framework for chiasma interference, particularly in autotetraploids (Mezard et al., 2007). Factors that tend to reduce effective recombination rates appear to lead to more efficient selection of adaptive epistatic combinations in diploids compared to autotetraploids.

Furthermore, Rehmsmeier's (2013) model excludes partial-preferential pairing. Partial-preferential pairing is a general feature of autotetraploids, including the plant species C. americanum (Etterson et al., 2007), as well as salmonid fish (Allendorf and Danzmann, 1997). How partial-preferential pairing facilitates or inhibits selection for epistatic combinations or even alleles that act additively is not understood. The models of Sybenga (1994), Stift et al. (2008) and Voorrips and Maliepaard (2012) provide a foundation for incorporating preferential pairing into models of selection in autotetraploids, as well as allotetraploids. Shifts toward strong preferential pairing and disomic inheritance in autotetraploids likely affects chromosomal gametic disequilibria and linkage disequilibria, which in turn may affect the process of selection.

In the context of disomic versus tetrasomic inheritance, there is an important distinction between modeling the formation of bivalents and tetravalents, using a parameter such as τ and partial-preferential pairing. In the Rehmsmeier (2013) model, even if τ=0, such that only bivalents form, inheritance is still tetrasomic because any of the four homologous chromosomes can form a bivalent. Partial-preferential pairing shifts inheritance towards disomy by having specific homologous chromosomes form bivalents (Stift et al., 2008; Stift et al., 2010). Our analysis assumed the probability of tetravalent formation during meiosis (τ) was its random expectation of 2/3. Despite this simplification, we were able to alter the rate of double reduction by changing the probability of paired-partner switches. In principle there could be an interaction between the probability of tetravalent formation and the probability of paired-partner switches on linkage and chromosomal gametic disequilibria and selection at two loci, but this interaction would have to manifest itself via a process other than double reduction because the probability of double reduction is function of the product of the probability of tetravalent formation and paired-partner switching (Rehmsmeier, 2013).

There is opportunity to broaden the investigation of two-locus selection in autotetraploids. This paper focused on a particular type of epistasis, but other models are possible, including a non-epistatic model. Characterization of two-locus equilibria in diploids was a classic problem of interest in the 1970s and 1980s (for example, Karlin, 1975; Hastings, 1981). It would be of interest to compare equilibria and stability properties between autotetraploids and diploids to gain insight into differences between the selection processes of autotetraploids and diploids. In principle, the variable space (such as the addition of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium) is greater in autotetraploids versus diploids, which may change the nature of equilibria and constraints in autotetraploids versus diploids. Furthermore, the nature of local adaptation in autotetraploids has not been theoretically studied for both single locus, as well as two loci. Ronfort et al. (1998) showed that variation in the rate of double reduction in autotetraploids affects FST, which may affect the process of local adaptation. Meirmans and Van Tienderen (2013) investigated the effect homoeologous allele exchange on F-statistics, including FST and FIT.

In addition, our paper did not study an alternate explanation for hybrid breakdown in C. americanum. An alternative explanation is non-adaptive, but still involves epistasis. It could be that subpopulations fix unique deleterious alleles due to random genetic drift and compensatory mutations then arise and fix that restore fitness (Etterson et al., 2007). In hybrids, deleterious-compensatory pairings are disrupted leading to a reduction in fitness. A theoretical analysis that compares the compensatory mutation process in diploids and autotetraploids would be informative about the potential role this has in C. americanum.

More broadly, adaptive gene combinations (Mayr, 1963) and polyploidy (Stebbins, 1950; Ramsey and Schemske, 1998) are potentially important mechanisms of speciation and diversification. An enhanced role of epistatic gene combinations in autopolyploids may facilitate divergence between allopatric populations and perhaps parapatric populations because of hybrid incompatibilities between populations. Adaptive epistatic combinations may form the basis of Bateson–Dobzhansky–Muller incompatibilities, which may contribute to speciation (Presgraves, 2010). That postzygotic reproductive incompatibilities appear to be weaker among polyploid hybrids than diploid hybrids in nature (Stebbins, 1950) goes against this claim that there may be an increased epistatic basis to population differences in polyploids versus diploids. Based on our results, selection for epistatic combinations is more efficient in diploids than autotetraploids if selection is weak and the deleterious effects of epistatic alleles when alone in a genotype are recessive. It could be that most polyploid species experience these conditions, but that there are exceptions, perhaps like C. americanum, in which selection is stronger and/or deleterious effects are more additive.

Conclusions

Our understanding of selection in polyploid populations is not well developed. This study indicates that there are conditions in which an adaptive epistatic gene combination is expected to be selected for more efficiently in an autotetraploid versus diploid population and that, more generally, selection for epistatic combinations may not be as restricted in autotetraploids as previously thought. Autotetraploid species incur an additional level of genetic disequilibrium that is distinct from linkage disequilibrium, namely chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. Chromosomal gametic disequilibrium for gametes that harbor the epistatic complex can achieve high values that are equal to or greater than linkage disequilibrium, and may therefore compensate for potentially faster rates of recombination in autotetraploids that breakdown linkage between adaptive epistatic alleles at the chromosome level.

References

Agrawal AF, Whitlock WC . (2011). Inferences about the distribution of dominance drawn from yeast gene knockout data. Genetics 187: 553–566.

Allendorf FW, Danzmann RG . (1997). Secondary tetrasomic segregation of MDH-B and preferential pairing of homeologues in rainbow trout. Genetics 145: 1083–1092.

Allendorf FW, Thorgaard GH . (1984) Tetraploidy and the evolution of salmonid fishes. In: Turner BJ (ed). Evolutionary Genetics of Fishes. Plenum: New York. pp 1–58.

Bennett JH . (1954). Panmixia with tetrasomic and hexasomic inheritance. Genetics 39: 150–158.

Bever JD, Felber F . (1992). The theoretical population genetics of autopolyploidy. In: Futuyma D, Antonovics J (eds). Oxford Surveys in Evolutionary Biology Vol. 8 Oxford University Press: New York, NY.

Bingham ET, Gross RW, Woodfield DR, Kidwell KK . (1994). Complementary gene interactions in alfalfa are greater in autotetraploids than diploids. Crop Sci. 34: 823–829.

Bogart JP . (1980). Evolutionary implications of polyploidy in amphibians and reptiles. In: Lewis WH (ed). Polyploidy: Biological Relevance. Plenum: New York. pp 341–378.

Butruille DV, Boiteux LS . (2000). Selection– mutation balance in polysomic tetraploids: impact of double reduction and gametophytic selection on the frequency and subchromosomal localization of deleterious mutations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97: 6608–6613.

Crow JF . (1954). Random mating with linkage in polysomics. Am. Nat. 88: 431–434.

de Winton D, Haldane JBS . (1931). Linkage in the tetraploid Primula sinesis. J. Genet. 24: 121–144.

Etterson JR, Keller SR, Galloway LF . (2007). Epistatic and cytonuclear interactions govern outbreeding depression in the autotetraploid Campanulastrum americanum. Evolution 61: 2671–2683.

Fisher RA . (1947). The theory of linkage in polysomic inheritance. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 233: 55–87.

Gallais A . (2003) Quantitative Genetics and Breeding Methods in Autopolyploid Plants. INRA: Paris.

Haldane JBS . (1926). A mathematical theory of natural selection and artificial selection. Part 3. Proc. Cambridge Phil. Soc. 23: 363–372.

Hastings A . (1981). Disequilibrium, selection, and recombination: limits in two-locus, two-allele models. Genetics 98: 656–668.

Hill RR . (1971). Selection in autotetraploids. Theor. Appl. Genet. 41: 181–186.

Husband BC, Baldwin S, Suda J . (2013) The incidence of polyploidy in natural plant populations: Major patterns and evolutionary processes. In: Leitch IJ et al (eds). Plant Genome Diversity vol. 2 Springer-Verlag: Vienna, Austria.

Karlin S . (1975). General two-locus selection models: some objectives, results and interpretations. Theor Popul Biol 7: 364–398.

Leitch AR, Leitch IJ . (2008). Genomic plasticity and the diversity of polyploid plants. Science 320: 481–483.

Lewis WH . (1980) Polyploidy: Biological Relevance. Springer: US.

Lu Y, Yang X, Tong X, Li X, Feng S, Wang Z et al. (2012). A multivalent three-point linkage analysis model of autotetraploids. Brief Bioinform. 14: 460–468.

Luo Z, Zhang RM, Kearsey MJ . (2004). Theoretical basis for genetic linkage analysis in autotetraploid species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101: 7040–7045.

Marcus M . (1990). Determinants of sums. Coll Math J 21: 130–135.

Mayr E . (1963) Animal Species and Evolution. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

Meirmans PG, Van Tienderen PH . (2013). The effects of inheritance in tetraploids on genetic diversity and population divergence. Heredity 110: 131–137.

Mezard C, Vignard J, Drouaud J, Mercier R . (2007). The road to crossovers: plants have their say. Trends Genet 23: 91–99.

Otto SP, Whitton J . (2000). Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annu Rev Genet 34: 401–437.

Paterson AH . (2005). Polyploidy, evolutionary opportunity, and crop adaptation. Genetica 123: 191–196.

Pecinka A, Fang W, Rehmsmeier M, Levy AA, Mittelsten Scheid O . (2011). Polyploidization increases meiotic recombination frequency in Arabidopsis. BMC Biol 9: 24.

Phillips R, Rab P . (2001). Chromosome evolution in the Salmonidae (Pisces): an update. Biol Rev 76: 1–25.

Presgraves DC . (2010). The molecular evolutionary basis of species formation. Nat Rev Genet 11: 175–180.

Ramsey J, Schemske DW . (1998). Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Genet. Ecol. Syst 29: 467–501.

Rehmsmeier M . (2013). A computational approach to developing mathematical models of polyploid meiosis. Genetics 193: 1083–1094.

Rieseberg LH, Sinervo B, Linder C, Ungerer MC, Arias DM . (1996). Role of gene interactions in hybrid speciation: evidence from ancient and experimental hybrids. Science 272: 741–745.

Ronfort J . (1999). The mutation load under tetrasomic inheritance and its consequences for the evolution of the selfing rate in autotetraploids. Genet. Res. 74: 31–42.

Ronfort J, Jenczewski E, Bataillon T, Rousset F . (1998). Analysis of population structure in autotetraploid species. Genetics 150: 921–930.

Rowe DE . (1982). Effect of gametic disequilibrium on selection in an autotetraploid population. Theor Appl Genet 64: 69–74.

Rowe DE, Hill RR . (1984). Effect of gametic disequilibrium on means and genetic variances of autotetraploid synthetic varieties. Theor. Appl. Genet. 68: 69–74.

Selmecki AM, Maruvka YE, Richmond PA, Guillet M, Shoresh N, Sorenson AL et al. (2015). Polyploidy can drive rapid adaptation in yeast. Nature 519: 349–352.

Simmons MJ, Crow JF . (1977). Mutations affecting fitness in Drosophila populations. Annu. Rev. Genet. 11: 49–78.

Stebbins GL . (1950) Variation and Evolution in Plants. Columbia University Press: New York, NY.

Stift M, Berenos C, Kuperus P, van Tienderen PH . (2008). Segregation models for disomic, tetrasomic and intermediate inheritance in tetraploids: a general procedure ppplied to Rorippa (Yellow Cress) microsatellite data. Genetics 179: 2113–2123.

Stift M, Reeve R, van Tienderen PH . (2010). Inheritance in tetraploid yeast revisited: segregation patterns and statistical power under different inheritance models. J. Evol. Biol 23: 1570–1578.

Sybenga J . (1994). Preferential pairing estimates from multivalent frequencies in tetraploids. Genome 37: 1045–1055.

Sved JA . (1964). The relationship between diploid and tetraploid recombination frequencies. Heredity 19: 585–596.

Voorrips RE, Maliepaard CA . (2012). The simulation of meiosis in diploid and tetraploid organims using various genetic models. BMC Bioinformatics 13: 248.

Wright S . (1938). The distribution of gene frequencies in populations of polyploids. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 24: 372–377.

Wu R, Ma CX . (2005). A general framework for statistical linkage analysis in multivalent tetraploids. Genetics 170: 899–907.

Wu SS, Wu R, Ma CA, Zeng ZB, Yang CK, Casella G . (2001). A multivalent pairing model of linkage analysis in autotetraploids. Genetics 159: 1339–1350.

Yant L, Hollister JD, Wright KM, Arnold BJ, Higgins JD, Franklin FC et al. (2013). Meiotic adaptation to genome duplication in Arabidopsis arenosa. Curr Biol 23: 2151–2156.

Acknowledgements

We thank the associate editor and reviewers for their very helpful comments. This work was supported by grants through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery program) and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Heredity website

Appendices

Appendix 1.

Diploid meiotic transition functions

This appendix provides the values for fij→k and mk→ℓ in matrix form for a diploid population. In the matrix that corresponds to fij→k values, it is assumed that rows correspond to genotypes (1) A1B1/A1B1, (2) A1B1/A1B2, (3) A1B1/A2B1, (4) A1B1/A2B2, (5) A1B2/A1B2, (6) A1B2/A2B1, (7) A1B2/A2B2, (8) A2B1/A2B1, (9) A2B1/A2B2 and (10) A2B2/A2B2, respectively. Furthermore, note that these are unordered genotypes such that A1B2/A1B1 is equivalent to A1B1/A1B2. Columns correspond to chromosomes (1) A1B1, (2) A1B2, (3) A2B1 and (4) A2B2, respectively. Rows and columns of the matrix that corresponds to mk→ℓ follows the same ordering of chromosomes in rows and columns.

Matrix corresponding to fij→k

Matrix corresponding to mk→ℓ

Appendix 2.

Autotetraploid gamete mode probabilities

Autotetraploid gamete mode probabilities from Rehmsmeier (2013) assuming potentially one paired-partner switch.

Appendix 3.

Autotetraploid meiotic transition functions

This appendix provides the values for fij→k and mk→ℓ in matrix form for an autotetraploid population. In the matrix that corresponds to fij→k values, it is assumed that rows correspond to ordered genotypes (1) A1B1/A1B1/A1B1/A1B1, (2) A1B1/A1B1/A1B1/A1B2, (3) A1B1/A1B1/A1B1/A2B1, (4) A1B1/A1B1/A1B1/A2B2, (5) A1B1/A1B1/A1B2/A1B2, (6) A1B1/A1B1/A1B2/A2B1, (7) A1B1/A1B1/A1B2/A2B2, (8) A1B1/A1B1/A2B1/A2B1, (9) A1B1/A1B1/A2B1/A2B2, (10) A1B1/A1B1/A2B2/A2B2, (11) A1B1/A1B2/A1B2/A1B2, (12) A1B1/A1B2/A1B2/A2B1, (13) A1B1/A1B2/A1B2/A2B2, (14) A1B1/A1B2/A2B1/A2B1, (15) A1B1/A1B2/A2B1/A2B2, (16) A1B1/A1B2/A2B2/A2B2, (17) A1B1/A2B1/A2B1/A2B1, (18) A1B1/A2B1/A2B1/A2B2, (19) A1B1/A2B1/A2B2/A2B2, (20) A1B1/A2B2/A2B2/A2B2, (21) A1B2/A1B2/A1B2/A1B2, (22) A1B2/A1B2/A1B2/A2B1, (23) A1B2/A1B2/A1B2/A2B2, (24) A1B2/A1B2/A2B1/A2B1, (25) A1B2/A1B2/A1B1/A2B2, (26) A1B2/A1B2/A2B2/A2B2, (27) A1B2/A2B1/A2B1/A2B1, (28) A1B2/A2B1/A2B1/A2B2, (29) A1B2/A2B1/A2B2/A2B2, (30) A1B2/A2B2/A2B2/A2B2, (31) A2B1/A2B1/A2B1/A2B1, (32) A2B1/A2B1/A2B1/A2B2, (33) A2B1/A2B1/A2B2/A2B2, (34) A2B1/A2B2/A2B2/A2B2 and (35) A2B2/A2B2/A2B2/A2B2, respectively. Columns correspond to gametes (1) A1B1/A1B1, (2) A1B1/A1B2, (3) A1B1/A2B1, (4) A1B1/A2B2, (5) A1B2/A1B2, (6) A1B2/A2B1, (7) A1B2/A2B2, (8) A2B1/A2B1, (9) A2B1/A2B2 and (10) A2B2/A2B2, respectively. Rows and columns of the matrix that corresponds to mk→ℓ follows the same ordering of gametes in rows and columns.

Matrix corresponding to fij→k

This matrix is provided in Supplementary Matrix 1a in PDF format and Supplementary Matrix 1b in LaTeX. Given the large dimensionality of the matrix, it is also provided in the form of a table (Supplementary Table 1c). Here, the row and column of the matrix are indicated in the first and second column of the table, respectively, and the value for fij→k in the third column.

Matrix corresponding to mk→ℓ

This matrix is provided in Supplementary Matrix 2a in PDF format and Supplementary Matrix 2b in LaTeX.

Appendix 4.

Linkage and chromosomal gametic disequilibria in autotetraploids

Tetraploid gamete frequencies can be decomposed into two components, one is the expected frequency of a gamete assuming independence between chromosomes, but that allows for linkage disequilibrium within a chromosome. The second component gives the deviation in gamete frequency from its expectation assuming independent inheritance of chromosomes. The expected frequency of a gamete  assuming independence between chromosomes, but that allows for linkage disequilibrium within a chromosome is

assuming independence between chromosomes, but that allows for linkage disequilibrium within a chromosome is  where the ± terms are positive when i=j and k=ℓ, respectively, and negative otherwise. The deviation in gamete frequency from its expectation assuming independent inheritance of chromosomes is

where the ± terms are positive when i=j and k=ℓ, respectively, and negative otherwise. The deviation in gamete frequency from its expectation assuming independent inheritance of chromosomes is  , such that together the observed tetraploid gamete frequency is

, such that together the observed tetraploid gamete frequency is  , where

, where  is the level of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium for gamete

is the level of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium for gamete  . Appendix 5 presents the matrix of tetraploid gamete frequencies presented in equation (1) (main text) in terms of D and

. Appendix 5 presents the matrix of tetraploid gamete frequencies presented in equation (1) (main text) in terms of D and  .

.

In terms of linkage disequilibrium, the matrix of chromosome frequencies is  . Here, there are in principle four deviations in chromosome frequencies from what is expected under linkage equilibrium. Yet, we know that these four deviations simplify to one number in absolute value, namely D. An approach to proving that the four deviations simplify to one disequilibrium in absolute value is to consider the chromosome-level recombination network (Figure A1) and the requirement that disequilibrium values satisfy the condition D11+D12+D21+D22=0, otherwise chromosome frequencies would not add to one. If we set all D values to equal zero and perturb D12=δ, then since chromosomes A1B1 and A2B2 share an allele with A1B2, their equilibrium values will both take on a value of −δ. In order to satisfy the relationship D11+D12+D21+D22=0, requires D21=δ. Together this perturbation analysis indicates that if D11=D22=D, then D12=D21=−D, and the determinant of the matrix

. Here, there are in principle four deviations in chromosome frequencies from what is expected under linkage equilibrium. Yet, we know that these four deviations simplify to one number in absolute value, namely D. An approach to proving that the four deviations simplify to one disequilibrium in absolute value is to consider the chromosome-level recombination network (Figure A1) and the requirement that disequilibrium values satisfy the condition D11+D12+D21+D22=0, otherwise chromosome frequencies would not add to one. If we set all D values to equal zero and perturb D12=δ, then since chromosomes A1B1 and A2B2 share an allele with A1B2, their equilibrium values will both take on a value of −δ. In order to satisfy the relationship D11+D12+D21+D22=0, requires D21=δ. Together this perturbation analysis indicates that if D11=D22=D, then D12=D21=−D, and the determinant of the matrix  is D, as expected.

is D, as expected.

Recombinant network at the chromosome level for both a diploid and autotetraploid (left) and segregant network at the gamete level for an autotetraploid (right). Vertices represent chromosomes (left) or gametes (right). Chromosomes can be generated by the recombination of adjacent chromosomes in the network (left). Similarly, gametes can be generated by segregation of a zygote formed by adjacent gametes in the network (right).

A similar analysis is possible in the context of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. Since the terms  already account for recombination at the chromosome level, we consider segregation at the gamete level to gain insight into how

already account for recombination at the chromosome level, we consider segregation at the gamete level to gain insight into how  values are related to each other (Figure A1). Over all, chromosomal gametic disequilibria must satisfy the relationship

values are related to each other (Figure A1). Over all, chromosomal gametic disequilibria must satisfy the relationship  , otherwise gamete frequencies would not add to one. If we associate a value

, otherwise gamete frequencies would not add to one. If we associate a value  with each of the gametes on inner vertices in Figure A1 then there are six

with each of the gametes on inner vertices in Figure A1 then there are six  values in total.

values in total.  and

and  values on outer vertices are negative functions of

values on outer vertices are negative functions of  values because if the level of disequilibrium of a gamete

values because if the level of disequilibrium of a gamete  increases, then the level of disequilibrium of gametes AiBj/AiBj and

increases, then the level of disequilibrium of gametes AiBj/AiBj and  must corresponding decrease by an equal amount because of the sharing of chromosomes. Together this simplifies the matrix in Appendix 5 to the matrix in Appendix 6. It is straightforward to show that

must corresponding decrease by an equal amount because of the sharing of chromosomes. Together this simplifies the matrix in Appendix 5 to the matrix in Appendix 6. It is straightforward to show that  for

for  values in the matrix in Appendix 6. Furthermore, a matrix with only the corresponding

values in the matrix in Appendix 6. Furthermore, a matrix with only the corresponding  terms in Appendix 6 (that is, the

terms in Appendix 6 (that is, the  terms are set to zero) has a determinant equal zero. Together, the sum and determinant of the six

terms are set to zero) has a determinant equal zero. Together, the sum and determinant of the six  values is consistent with them forming an irreducible and independent set of chromosomal gametic disequilibriums. Accordingly, for a two-locus, two-allele autotetraploid system there are six distinct values of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. As shown in Appendix 7, the determinant of the matrix in Appendix 6 is

values is consistent with them forming an irreducible and independent set of chromosomal gametic disequilibriums. Accordingly, for a two-locus, two-allele autotetraploid system there are six distinct values of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. As shown in Appendix 7, the determinant of the matrix in Appendix 6 is

which equals the overall level of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium. The determinant is independent of D confirming it does not contribute to  . Furthermore, the determinant indicates that all possible products

. Furthermore, the determinant indicates that all possible products  contribute to the overall level of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium except for products involving gametes who when paired to form a zygote either do not generate new types of gametes during segregation or generate gametes on outer vertices of Figure A1. For example, the product

contribute to the overall level of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium except for products involving gametes who when paired to form a zygote either do not generate new types of gametes during segregation or generate gametes on outer vertices of Figure A1. For example, the product  is not part of the overall level of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium and involves gametes that when combined into a zygote that then undergoes segregation either generates the same gametes that formed the zygote (A1B1/A1B2, A1B1/A2B1 or A1B2/A2B1) or gametes on outer vertices of Figure A1 (A1B1/A1B1, A1B2/A1B2 or A2B1/A2B1). The other products that are not part of

is not part of the overall level of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium and involves gametes that when combined into a zygote that then undergoes segregation either generates the same gametes that formed the zygote (A1B1/A1B2, A1B1/A2B1 or A1B2/A2B1) or gametes on outer vertices of Figure A1 (A1B1/A1B1, A1B2/A1B2 or A2B1/A2B1). The other products that are not part of  are

are  ,

,  and

and  .

.

Appendix 5.

Gamete frequency matrix for autotetraploids: unsimplified

This matrix of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium is provided in Supplementary Matrix 3a in PDF format and Supplementary Matrix 3b in LaTeX. The matrix assumes that gametes  and

and  have the same expected frequency provided there is no preferential pairing or sex differences in gamete frequencies.

have the same expected frequency provided there is no preferential pairing or sex differences in gamete frequencies.

Appendix 6.

Gamete frequency matrix for autotetraploids: simplified

This matrix of chromosomal gametic disequilibrium is provided in Supplementary Matrix 4a in PDF format and Supplementary Matrix 4b in LaTeX.

Appendix 7.

The determinant of the matrix of gamete frequencies in autotetraploids

The matrix in Appendix 6 can be written as the sum of two matrices, in which one matrix consists of terms  and the second matrix terms involving

and the second matrix terms involving  . Let MD denote the matrix consisting of terms

. Let MD denote the matrix consisting of terms  and

and  the matrix involving terms

the matrix involving terms  , such that the matrix in Appendix 6 is equal to

, such that the matrix in Appendix 6 is equal to  . The determinant of the matrix sum

. The determinant of the matrix sum  can be written as

can be written as  (Marcus, 1990), where the outer sum is over i, which takes values from 0,…,4 for the 4 × 4 matrix

(Marcus, 1990), where the outer sum is over i, which takes values from 0,…,4 for the 4 × 4 matrix  and the inner sum is over Ω, which consists of all subsets of numbers of length i from the set {1,2,3,4}. XΩ is a 4 × 4 matrix consisting of rows from either MD or

and the inner sum is over Ω, which consists of all subsets of numbers of length i from the set {1,2,3,4}. XΩ is a 4 × 4 matrix consisting of rows from either MD or  , or both, such that a subset in Ω consists of the rows drawn from MD and placed in corresponding rows in XΩ, while the remaining rows are filled by corresponding rows in

, or both, such that a subset in Ω consists of the rows drawn from MD and placed in corresponding rows in XΩ, while the remaining rows are filled by corresponding rows in  . When i=0, XΩ=MD and when i=4,

. When i=0, XΩ=MD and when i=4,  , but the determinants of both MD and