Abstract

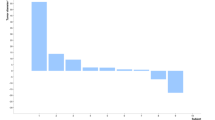

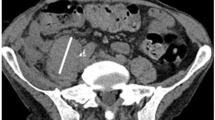

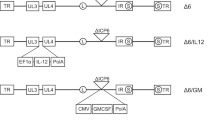

Our pre-clinical studies demonstrated that intratumoral vaccination with a recombinant oncolytic type 2 adenovirus overexpressing the heat shock protein (HSP)70 protein, designated as H103, can inhibit primary and metastatic tumors through enhanced oncolytic activity and HSP-mediated immune responses against shared and mutated tumor antigens. In the pre-clinical studies of local H103 administration, no significant toxicity was observed in the animal trials with mice, cavy or rhesus monkeys. A phase I clinical trial of intratumoral injection of H103 was conducted in the patients with advanced solid tumors. A total of 27 patients were injected intratumorally with H103 in a dose-escalation study from a dose of 2.5 × 107 to 3.0 × 1012 viral particles (VPs). The maximum tolerated dose of H103 was not defined. Two patients developed dose-limiting toxicities of grade III fever at the dose of 1.5 × 1012 VP and transient grade IV thrombocytopenia at the dose of 3.0 × 1012 VP. The common adverse events were mainly mild to moderate (grade I/II) in nature, including fever, mild injection-site reaction, leucopenia, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia and hypochromia. The objective response (complete response+partial response) to H103-injected tumors was 11.1% (3/27), and the clinical benefit rate (complete response+partial response+minor response+stable disease) was 48.1%. Interestingly, transient and partial regression of distant, uninjected tumors was observed in three patients. The numbers of immune cells (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and natural killer cells) were elevated after H103 administration, but without statistical significance. This phase I trial demonstrates that intratumoral administration of H103 can be safely applied to cancer patients and shows promising clinical antitumor activity, warranting a further clinical investigation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bischoff JR, Kirn DH, Williams A, Heise C, Horn S, Muna M et al. An adenovirus mutant that replicates selectively in p53-deficient human tumor cells. Science 1996; 274: 373–375.

Ganly I, Kirn D, Eckhardt G, Rodriguez GI, Soutar DS, Otto R et al. Phase I study of Onyx-015, an E1B attenuated adenovirus, administered intratumorally to patients with recurrent head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2000; 6: 798–806.

O’Shea CC, Johnson L, Bagus B, Choi S, Nicholas C, Shen A et al. Late viral RNA export, rather than p53 inactivation, determines ONYX-015 tumor selectivity. Cancer Cell 2004; 6: 611–623.

Garber K . China approves world's first oncolytic virus therapy for cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98: 298–300.

David HK . The end of the beginning: oncolytic virotherapy achieves clinical proof-of-concept. Mol Ther 2006; 13: 237–238.

Yu W, Fang H . Clinical trials with oncolytic adenovirus in China. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2007; 7: 659–670.

Xia ZJ, Chang JH, Zhang L, Jiang WQ, Guan ZZ, Liu JW et al. Phase III randomized clinical trial of intratumoral injection of E1B gene-deleted adenovirus (H101) combined with cisplatin-based chemotherapy in treating squamous cell cancer of head and neck or esophagus. Ai Zheng 2004; 23: 1666–1670.

Nover L, Scharf KD . Heat shock proteins. In: Nover L (ed). Heat Shock Response. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1991, pp 41–128.

Georgopoulos C, Welch WJ . Role of the major heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Cell Biol 1993; 9: 601–634.

Tamura Y, Peng P, Liu K, Daou M, Srivastava PK . Immunotherapy of tumors with autologous tumor-derived heat shock protein preparations. Science 1997; 278: 117–120.

Srivastava P . Interaction of heat shock proteins with peptides and antigen presenting cells: chaperoning of the innate and adaptive immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol 2002; 20: 395–425.

Becker T, Hartl FU, Wieland F . CD40, an extracellular receptor for binding and uptake of Hsp70–peptide complexes. J Cell Biol 2002; 158: 1277–1285.

Binder RJ, Han DK, Srivastava PK . CD91: a receptor for heat shock protein gp96. Nat Immunol 2000; 1: 151–155.

Binder RJ, Blachere NE, Srivastava PK . Heat shock protein-chaperoned peptides but not free peptides introduced into the cytosol are presented efficiently by major histocompatibility complex I molecules. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 17163–17171.

Hunt S . Technology evaluation: HspE7, StressGen Biotechnologies Corp. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2001; 3: 413–417.

Janetzki S, Palla D, Rosenhauer V, Lochs H, Lewis JJ, Srivastava PK . Immunization of cancer patients with autologous cancer-derived Hsp gp96 preparations: a pilot study. Int J Cancer 2000; 88: 232–238.

Testori A, Richards J, Whitman E, Mann GB, Lutzky J, Camacho L et al. Phase III comparison of vitespen, an autologous tumor-derived heat shock protein gp96 peptide complex vaccine, with physician's choice of treatment for stage IV melanoma: the C-100-21 Study Group. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 955–962.

Wood C, Srivastava P, Bukowski R, Lacombe L, Gorelov AI, Gorelov S et al. An adjuvant autologous therapeutic vaccine (HSPPC-96; vitespen) versus observation alone for patients at high risk of recurrence after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase III trial. Lancet 2008; 372: 145–154.

Huang XF, Ren W, Rollins L, Pittman P, Shah M, Shen L et al. A broadly applicable, personalized heat shock protein-mediated oncolytic tumor vaccine. Cancer Res 2003; 63: 7321–7329.

Neckers L . Heat shock protein 90: the cancer chaperone. J Biosci 2007; 32: 517–530.

Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S . Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature 2002; 417: 618–624.

Goetz MP, Toft DO, Ames MM, Erlichman C . The Hsp90 chaperone complex as a novel target for cancer therapy. Ann Oncol 2003; 14: 1169–1176.

O’Shea CC, Soria C, Bagus B, McCormick F . Heat shock phenocopies E1B-55K late functions and selectively sensitizes refractory tumor cells to ONYX-015 oncolytic viral therapy. Cancer Cell 2005; 8: 61–74.

Chuah MK, Collen D, VandenDriessche T . Biosafety of adenoviral vectors. Curr Gene Ther 2003; 3: 527–543.

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 205–216.

Thorne SH, Brooks G, Lee YL, Au T, Eng LF, Reid T . Effects of febrile temperature on adenoviral infection and replication: implications for viral therapy of cancer. J Virol 2005; 79: 581–591.

O’Shea CC, Soria C, Bagus B, McCormick F . Heat shock phenocopies E1B-55K late functions and selectively sensitizes refractory tumor cells to ONYX-015 oncolytic viral therapy. Cancer Cell 2005; 8: 61–74.

Buller RE, Runnebaum IB, Karlan BY, Horowitz JA, Shahin M, Buekers T et al. A phase I/II trial of rAd/p53 (SCH 58500) gene replacement in recurrent ovarian cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 2002; 9: 553–566.

Hecht JR, Bedford R, Abbruzzese JL, Lahoti S, Reid TR, Soetikno RM et al. A phase I/II trial of intratumoral endoscopic ultrasound injection of ONYX-015 with intravenous gemcitabine in unresectable pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 555–561.

Hecht JR, Bedford R, Abbruzzese JL, Lahoti S, Reid TR, Soetikno RM et al. Phase II clinical trial of intralesional administration of the oncolytic adenovirus ONYX-015 in patients with hepatobiliary tumors with correlative p53 studies. Clin Cancer Res 2003; 9: 693–702.

Xu RH, Yuan ZY, Guan ZZ, Cao Y, Wang HQ, Hu XH et al. Phase II clinical study of intratumoral H101, an EI B deleted adenovirus, in patients with cancer. China Oncol 2004; 14: 12–18.

McShine RL, Sibinga S, Brozovic B . Differences between the effects of EDTA and citrate anticoagulants on platelet count and mean platelet volume. Clin Lab Haematol 1990; 12: 277–285.

Leen AM, Rooney CM, Foster AE . Improving T cell therapy for cancer. Annu Rev Immunol 2007; 25: 243–265.

Novellino L, Castelli C, Parmiani GA . Listing of human tumor antigens recognized by T cells: March 2004 update. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2005; 54: 187–207.

Czerkinsky C, Andersson G, Ekre HP, Nilsson LA, Klareskog L, Ouchterlony O . Reverse ELISPOT assay for clonal analysis of cytokine production. I. Enumeration of gamma-interferon-secreting cells. J Immunol Methods 1988; 110: 29–36.

Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJ, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI et al. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 1996; 274: 94–96.

Goodman SN, Zahurak ML, Piantadosi S . Some practical improvements in the continual reassessment method for phase I studies. Stat Med 1995; 14: 1149–1161.

Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A . Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer 1981; 47: 207–214.

Acknowledgements

This phase I clinical study of H103 was partially supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (2002AA2Z3340). We gratefully acknowledge Dr Shun-Jiang Yu, Dr Hai-Feng Feng and Dr Rong Zhu for their review of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, JL., Liu, HL., Zhang, XR. et al. A phase I trial of intratumoral administration of recombinant oncolytic adenovirus overexpressing HSP70 in advanced solid tumor patients. Gene Ther 16, 376–382 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/gt.2008.179

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gt.2008.179

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Personalizing Oncolytic Immunovirotherapy Approaches

Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy (2024)

-

Potentiating prostate cancer immunotherapy with oncolytic viruses

Nature Reviews Urology (2018)

-

Ki67 targeted strategies for cancer therapy

Clinical and Translational Oncology (2018)

-

Oncolytic viruses: emerging options for the treatment of breast cancer

Medical Oncology (2017)