Abstract

Purpose:

Evidence-based guidelines recommend that all newly diagnosed colon cancer be screened for Lynch syndrome (LS), but best practices for implementing universal tumor screening have not been extensively studied. We interviewed a range of stakeholders in an integrated health-care system to identify initial factors that might promote or hinder the successful implementation of a universal LS screening program.

Methods:

We conducted interviews with health-plan leaders, managers, and staff. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis began with a grounded approach and was also guided by the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM).

Results:

We completed 14 interviews with leaders/managers and staff representing involved clinical and health-plan departments. Although stakeholders supported the concept of universal screening, they identified several internal (organizational) and external (environment) factors that promote or hinder implementation. Facilitating factors included perceived benefits of screening for patients and organization, collaboration between departments, and availability of organizational resources. Barriers were also identified, including: lack of awareness of guidelines, lack of guideline clarity, staffing and program “ownership” concerns, and cost uncertainties. Analysis also revealed nine important infrastructure-type considerations for successful implementation.

Conclusion:

We found that clinical, laboratory, and administrative departments supported universal tumor screening for LS. Requirements for successful implementation may include interdepartmental collaboration and communication, patient and provider/staff education, and significant infrastructure and resource support related to laboratory processing and systems for electronic ordering and tracking.

Genet Med 18 2, 152–161.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States.1 Approximately 2–3% of CRC cases are attributable to a genetic predisposition associated with germline mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes,2 an autosomal dominant condition known as Lynch syndrome (LS) (OMIM #120435). LS is the most common form of hereditary CRC3 and can be recognized by either family history criteria or a characteristic molecular profile in the tumor. Based on evidence that universal tumor testing would save lives,4,5 several national groups have recommended that all CRC tumors, regardless of patients’ age or family history, be screened for LS using laboratory assays.6

Two laboratory-based assays are used today to screen for LS—microsatellite instability (MSI) and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Defects in the MMR pathway cause errors in DNA replication, known as MSI, and can be seen in approximately 15% of sporadic colon tumors and in 85% of tumors in patients with LS.7 MSI testing is performed on the DNA extracted from the tumor, with sensitivity and specificity to detect germ-line MMR mutations of 85 and 90%, respectively.8,9,10,11,12 IHC detects underexpression of proteins encoded by MMR genes in the MMR pathway.13,14 However, because not all germline mutations result in absent MMR proteins in the tumor,11 the sensitivity of IHC testing for identifying germline mutations is approximately 83% and specificity is approximately 90%.4 Thus, MSI and IHC testing are laboratory-based LS screening tests because they cannot distinguish between somatic versus germline causes of MSI in tumors.

Although clinical criteria for screening LS exist (e.g., Bethesda or Amsterdam criteria), more than half of patients meeting clinical criteria do not receive screening.15,16 Seventy-one percent of the 41 National Cancer Institute-Comprehensive Cancer Centers across the United States conducted laboratory-based universal LS screening in 2009, yet only 15% of community hospital cancer programs regularly screened for LS using tumor testing methods.17 Furthermore, using data from a 2004–2009 study of seven health maintenance organizations (HMOs) found that none was performing universal LS screening, and fewer than 4% of colon cancer patients were tested for LS.18

Although uptake of universal LS screening is less than optimal, we understand little about why. Most research on LS screening implementation comes from one type of stakeholder (e.g., physician or genetic counselor) or focuses on high-risk or research populations; data from a broader organizational perspective or population are more limited.19 Research has shed light on some possible barriers: physician interviews at mostly university-affiliated medical centers have raised questions about the ability to follow up with at-risk patients, and there are concerns about consent, cost-effectiveness, and ethical issues regarding informing relatives20 about test results. Hall21 discusses concerns about patient psychosocial burdens and gaps in clinical expertise, and a national survey of genetic counselors identified implementation barriers regarding variability in returning results, cost uncertainties, and lack of clinical/leadership or buy-in.22

To better understand the initial factors involved in implementing universal LS screening in an integrated health-care system, we conducted interviews with health-plan and clinical stakeholders in a large HMO during the early phase of their implementation deliberations. Specifically, we interviewed individuals to gather a range of perspectives from health-plan leaders/managers and from frontline staff to uncover early challenges and facilitators to the successful implementation of LS screening. The results are the focus of this report.

Materials and Methods

Background and study site

Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) is an integrated HMO that serves approximately 490,000 health-plan members in the metropolitan area of Portland, Oregon. KPNW comprises the following three primary and interrelated organizational structures: (i) a private corporation of medical doctors that contract to provide care to KPNW health-plan members, (ii) the KPNW health plan, and (iii) related KP-owned and managed hospitals and clinics. All patient care is documented through an electronic medical record (EMR). Prior to this study, we estimated that only 5% of CRCs were screened for LS in this health system, with KPNW relying on provider or self-referrals to the medical genetics department for screening based on clinical criteria.

Recruitment and participants

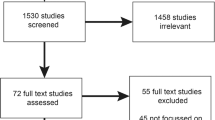

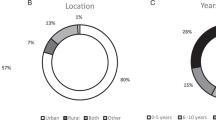

We recruited leaders (senior-level and managers) and staff (frontline) representing both the medical and the health-plan sides of the organization for qualitative interviews. We recruited participants from a variety of departments, including pathology, oncology, medical genetics, gynecology, surgery, laboratory services, and administration. We used a purposeful, role-based sample,23 recruiting participants on the basis of either their role or their experience with LS screening or because colleagues or interviewees identified them as having an important perspective. Participants were recruited via e-mail; we followed up by telephone or e-mail with those expressing interest. We continued to recruit until no “new” potential interview participants were identified to us. Interviews occurred during August 2012–April 2013 were conducted over the telephone or in person and lasted 45–60 min.

Data-collection methods

Qualitative methods are effective strategies for analyzing complex social phenomena23,24 and can reveal information unanticipated by researchers.25,26,27 Thus, the research team designed an open-ended interview guide based on prior experience and a literature review.25,26,27 We conducted interviews in two phases. We first interviewed staff engaged with the day-to-day responsibilities of LS screening (e.g., genetic counselors, pathologists) and asked about current role, perceived impact on department workflows and staff, concerns about implementing universal screening, and factors that hinder or facilitate screening. Interviewees from this first round emphasized the importance of including all potential stakeholders who may have an opinion about or role in universal LS implementation. Given this feedback, in our second round of interviews we solicited input from health-plan leaders or managers, such as department chiefs and other decision makers in key department areas. We broadened the scope of our questions beyond daily implementation details and focused on the potential to establish universal LS screening as an organizational standard of care. We asked about the perceived value of universal screening, what factors influence practice change, organizational barriers, and facilitators, and who might serve as organizational champions of universal screening. All interviews were conducted by a trained qualitative interviewer (J.D.) and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interview procedures and materials were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research.

Conceptual framework and analysis process

We used the Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM)28 to help orient our analysis of the interview data. PRISM is a concrete, conceptual framework to help researchers or organizations identify and understand the factors potentially needed to foster implementation and maintenance of a health-care program/intervention. PRISM has several interrelating core domains: (i) the program (intervention) viewed from the organization perspective and patient perspective; (ii) the recipients (organization and patient characteristics); (iii) the external environment (e.g., regulations, competition); and (iv) the organizations’ implementation and sustainability infrastructure. Figure 1 shows these domains and describes related elements that might be considered within each.28 A unique aspect of PRISM is that the organizational perspectives and characteristics are considered at three levels: senior leaders, midlevel managers, and frontline workers. The framework suggests documenting and defining key factors of internal (organizational) and external (environment) influences. Given that our interviews were with a range organizational staff and did not directly include patients, we broadly reviewed our interview data from the point of view of the following PRISM domains: program (organizational characteristics); recipients (organizational perspectives); external environment; and implementation infrastructure. Within the context of this framework, we also used an open-coding, grounded theory approach29 to explore the intersection of external and internal facilitators or challenges from the perspective of various staff (leaders, managers, and frontline).

Specifically, aided by the use of a qualitative software package (NVivo, QRS International (Americas), Burlington, MA), we conducted a thematic content analysis of the transcribed interviews using qualitative coding and interpretation techniques.23,29,30 Analysis occurred in two stages. First, a team member (J.D.) trained in open-coding techniques29 coded the interviews within NVivo by marking passages of text with phrases indicating the content. Reports were then generated of coded text and the research team reviewed them, resulting in initial themes. Next, themes were reviewed by comparing them against the raw interview transcripts and the PRISM domains defined above. This allowed us to further refine themes and clarify interpretations of the data. We explored any differences or areas of convergence across interviews, comparing and contrasting themes that emerged from the staff and leader interviews. An expert (by education, training, and experience) in qualitative analysis who did not conduct the interviews (J.S.) conducted this process. This allowed for both an insider (J.D.) and an outsider (J.S.) review of the interview data. Refined themes were shared again with the research team and project Advisory Board in an ongoing process until the group reached consensus on interpretation.

Results

Of the 15 participants recruited, we completed 14 interviews (one declined), 7 with frontline staff and 7 with leaders/managers. Overall, we interviewed 8 female and 6 male participants, with almost half (43%) having more than 10 years of experience with the organization ( Table 1 ). Here, we report on external (environment) and internal (organizational) factors that either facilitated implementation of universal LS screening ( Table 2 ) or presented challenges ( Table 3 ).

External (environment) facilitators

Participants described a national trend pushing organizations toward universal LS screening, shaped by literature on the benefits of LS screening, and recognition that medicine is moving toward genetic screening as a standard. Awareness of other health-care organizations having implemented universal LS screening also contributed to participants’ sense of a national movement. Participants described a “shift” in views among peers that universal LS screening is a long overdue service that should be implemented. Although both staff and leaders cited the national trend and the influence of others, leaders cited these more often.

Both staff and leaders cited potential benefits to patients and their family members as an important external factor. A majority of leaders believed that LS screening offers equal benefit to both the patient and his or her family members. Staff and leaders strongly believed that a universal LS screening program could save the lives of the primary patient and family members by helping to detect related cancers early and directly influence current and follow-up care.

Internal (organizational) facilitators

Staff and leaders also cited an overarching organizational advocacy for universal LS screening as a strong driver to implementation. Half or more of both groups believed that universal LS screening is a worthwhile goal and the “right thing to do” for patients. They cited awareness of colleagues within their own department or in other departments having a similar supportive stance. This advocacy was bolstered by a belief that the confirmation of a diagnosis from screening adds value to patient care by guiding surgery, follow-up tests, and surveillance. A majority of leaders also recognized that implementing LS screening as a standard practice would align with the organization’s overall goals to improve CRC screening and treatment.

Respondents told us that positive interdepartment relationships and experienced staff were important facilitators. A majority of both staff and leaders cited a history of innovative, flexible, and collaborative communication across the involved departments. Additionally, respondents viewed the staff of participating departments (pathology and genetics) as skilled and experienced, having already designed and implemented workflows for other universal genetic screening tests (such as Her-2 neu testing of breast cancers) that could be modified for LS screening. Respondents said the combination of historical collaboration, communication, and experienced staff gave them confidence in the organization’s ability to design a universal LS program.

Participants also described organizational resources, such as testing equipment, and prior experience with other genetic screening programs that demonstrated minimal negative impact on resources and staff time. Leaders expressed that potential cost savings was a facilitator, and most believed the costs of setting up and maintaining a universal LS screening program would be outweighed by eventual cost savings from preventing patients from moving into advanced disease.

External (environment) challenges

Overall lack of awareness about what is normative in the field of CRC screening was specifically cited by leaders as a hindrance. They expressed a belief that the United States is generally “behind the times” in prevention and screening options for CRC compared with other countries. More than half of the leaders felt the public lacked awareness about CRC screening in general and that there was even less public understanding about LS screening. A majority of leaders expressed not knowing who else was implementing universal LS screening or what national recommendations, if any, existed to guide implementation efforts.

Both leaders and staff cited the perceived lack of clarity and agreement related to LS screening guidelines as an implementation barrier. Leaders expressed that the national-criteria recommendations were still too variable to concretely guide practice change. For example, more than half of those interviewed expressed a sense of uncertainty regarding how to best transition from the current family history–based criteria (Amsterdam or Bethesda) into a universal screening program. Participants perceived variability in recommended guidelines, which added to uncertainty about how to design and implement a program. Participants were unclear regarding the most appropriate criteria for identifying patients or which screening test (MSI, IHC, or both) should be chosen.

Interviewees less frequently described patient and family member considerations as external barriers, primarily citing that family members who are not a part of the same health plan would be difficult to track and contact after diagnosis. A few respondents also mentioned concerns about whether a consenting process would be needed for tumor screening and, if so, whether the need for consent could create a barrier. Some leaders expressed concern that patients may decline laboratory testing due to fear of health insurance discrimination that could follow.

Internal (organizational) challenges

Participants described several historical organizational barriers. LS screening has been perceived as a difficult process to set up because it involves multiple, complex factors and related decisions. Leaders, in particular, articulated this as an ongoing barrier. Factors related to the complexity barrier include (i) concern that there would not be sufficient time within the context of already heavy workloads for needed staff to navigate through the decision points in such a process, (ii) lack of a clear champion to lead such an effort and obtain commitment and consensus across departments, and (iii) uncertainty regarding which department(s) should “own” the screening program.

Participants identified department constraints on universal LS screening. A majority described how departments involved with implementing LS screening would be resistant to any perceived increase in workload without an equivalent match in staffing. Additionally, interviewees described how this sensitivity to increases in workload, along with budget constraints for involved departments, amplified some departments’ resistance to “own” the program.

Interviewees also identified resource and cost uncertainties as barriers, including recognition that genetic screening services can be expensive to provide, and that these services may not generate income. Participants described how challenging it is to determine whether cost savings could be realized if a program is implemented because some benefits may be for family members who are not health-plan members. This is further complicated by uncertainties about how to fund the screening program, including uncertainty about which department budgets might help pay for it. These cost barriers were more often described by leaders.

Key implementation and infrastructure factors

We also asked participants in an open-ended fashion for their perspective on what would be needed for developing, implementing, and sustaining a successful universal LS screening program for their organization. Analysis of participant responses revealed nine key considerations: (i) establishing/standardizing roles, tasks, and workflows; (ii) developing electronic structures for ordering and tracking results; (iii) finding champions and involving key departments; (iv) determining the laboratory location and needs for processing the screening test; (v) conducting a business case analysis; (vi) establishing partnerships and best practices with other organizations that have implemented universal LS screening; (vii) selecting the appropriate screening method (MSI, IHC, or both) for the organization; (viii) conducting an awareness/education campaign for all staff and patients; and (ix) determining which department(s) within the organization would own and manage the screening program. The details of these key implementation and infrastructure factors are presented in Table 4 in the order of how often they were mentioned by our interviewees.

Discussion

Our interviews revealed that many external and internal factors influence an organization’s decision to implement universal LS tumor screening as a part of standard care. Respondents revealed nine critical, and often interrelated, organizational decision points that reflect elements found in the core domains of PRISM. The top three considerations from our interviewees centered broadly on establishing support and developing infrastructure and encompass PRISM elements such as management/leader support, clinical leadership, shared goals and cooperation, coordination across departments, staffing, burden, systems and training, data and decision support, adaptable protocols and procedures, and having a dedicated team. For example, our respondents talked a great deal about the importance of creating standardized roles and task expectations, and having clear communication and documentation workflows across involved functions (e.g., pathology, genetics). Vital to that effort, our interviewees described the need to develop and build EMR structures to support staff in electronically placing and tracking orders and related results. Deciding who has ultimate responsibility for program execution and monitoring was further cited as integral to any implementation effort, and for establishing clear roles and task expectations to promote ongoing sustainability.

Selecting the laboratory (external versus internal) for processing the chosen screening test was also a major focus of discussion, as were highlights of the PRISM perspective such as the relationship between elements of readiness, strength of the evidence base, observability of results, and infrastructure needs. Although knowledge and understanding of the selected screening method (MSI or IHC) may help in selecting the laboratory decision for some organizations, our respondents suggested considering staffing expertise, ease of integration into existing structures, and accuracy/timeliness of results as additional considerations. Hampel et al.31 showed that IHC and MSI are similar in their high sensitivity for detecting LS. Given this, issues of staffing expertise and EMR/workflow integration may prove to be more germane implementation infrastructure considerations.

Stakeholder buy-in, engagement, and involvement were described as critical. Neglecting these considerations has been found to be a barrier for others seeking universal LS screening.22 As suggested by our interviewees, identifying champions for universal LS screening from key departments, involving them in educating their colleagues, and integrating their input early into planning and decision making are vital to successful program implementation.

However, even with strong organizational support and participation, factors from the external environment may create potential challenges to implementation. Our respondents described several potential barriers from the external environment, including their concerns about unclear universal screening guidelines, lack of knowledge about what other institutions were doing, and tracking family members across different health plans. Comments about lack of clear guidelines highlights stakeholders’ concerns with the Bethesda and Amsterdam criteria, and emphasizes the potential implementation impact of the PRISM elements pertaining to strength of the evidence, competition, and the regulatory environment. For LS screening, recommendations from two national workgroups5,6 may help address these uncertainties because they recommend screening for all CRC patients. In 2009, the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group recommended that all CRC tumors be screened for LS using laboratory assays. Furthermore, in 2013, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) published practice guidelines for CRC that included testing all colorectal tumors. Additionally, stakeholder concerns about tracking and follow-up with family members belonging to different health plans may become less of an issue as more health plans institute universal LS screening. In the future, health plans will need to acknowledge the public health benefit of population-based LS screening. The ability to electronically view, request, and track results across organizations will help to coordinate this effort

A primary organizational (internal) barrier discussed by our interviewees centered on needed resources and potential costs to implement a universal LS screening program. Participants viewed understanding and identifying costs and potential resources as a complex, time-consuming process. Several published cost-effectiveness studies may help address these concerns. One study modeled a hypothetical cohort of 150,000 newly diagnosed CRC patients and found universal MSI and IHC screening to be cost-effective, with IHC having the lowest cost per life-year saved.32 Another utilized Markov modeling of newly diagnosed CRC patients also found IHC to be the most cost-effective approach.33 The number of relatives tested was the key driver in cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, Gudgeon et al.34 based their model on a cohort of CRC patients from their health-care system, reporting MSI as substantially less cost-effective than IHC.

Our study had limitations. Our small sample size (n = 14) may limit the generalizability of our findings to other settings. Our selection of participants by convenience and role may have led to selection bias, and social desirability bias (participants telling us what they think we want to hear) may have limited accuracy. Conducting the interviews in two phases may have contributed to inconsistencies in interpretation of the data because we did not go back and reinterview frontline staff with some of the additional questions that were added to the interview guide for leaders. Additionally, although we cannot discern whether stakeholders’ responses represent the feelings of noninterviewed staff or the perspectives of health-plan leaders/managers across the system, responses were sufficiently consistent that we could identify themes and patterns. Our findings are also limited to the timeframe in which interviews were conducted during the very initial stages of considering universal LS screening; therefore, they focus primarily on early implementation barriers and facilitators. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted as part of a study on the implementation of universal LS screening within this organization, so awareness of the study could have had an impact on responses. Thus, the organization reflects a state where there is at least some institutional buy-in to considering a universal LS screening program. Although the details of some organizational and infrastructure considerations under some themes may be unique to the organization undergoing study and therefore less generalizable, the overarching themes may still be useful guideposts. Finally, the patient perspective is limited to the interpretations of the organizational staff interviewed and does not reflect opinions derived directly from patients.

We used several strategies to improve the thematic trustworthiness of our data,23 including using a trained interviewer and interview guide to improve consistency, obtaining a range of viewpoints representing different roles and functions within the organization, using a formal team-based approach to analysis that included both an “insider” and “outsider” review of the data, engaging in a two-step analysis process that incorporated both standard qualitative open-coding techniques as well as guidance from a conceptual framework, and reviewing our findings with study staff and advisory board members to challenge and improve consistency of interpretation. Future research may explore post-analytical issues after tumor testing, including workflows, communication, and best practices between genetic counselors, patients, and related family members. Additionally, given that we did not interview patients or their family members in this stage, researchers may want to explore LS screening from a family perspective to help create a paradigm shift that would allow realization of the full potential of LS screening as a population-based approach.

Identifying early challenges and key infrastructure factors may help similar organizations incorporate universal LS screening. We observed widespread support across stakeholder groups in the health system we studied. Successful implementation, however, will require ongoing interdepartmental collaboration and communication, patient and provider/staff education, and significant infrastructure and resource support, particularly for laboratory processing and electronic ordering and tracking.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

American Cancer Society. Colorectal cancer facts & figures: 2011–2013. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/colorectalcancerfactsfigures/colorectal-cancer-facts-figures-2011–2013. Accessed 4 August 2012.

Ionov Y, Peinado MA, Malkhosyan S, Shibata D, Perucho M. Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis. Nature 1993;363:558–561.

Stoffel EM, Kastrinos F. Familial colorectal cancer, beyond Lynch syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1059–1068.

Palomaki GE, McClain MR, Melillo S, Hampel HL, Thibodeau SN. EGAPP supplementary evidence review: DNA testing strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome. Genet Med 2009;11:42–65.

Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: genetic testing strategies in newly diagnosed individuals with colorectal cancer aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome in relatives. Genet Med 2009;11:35–41.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer (version 1.2013), 2013, http://www.nccn.org. Accessed 5 July 2014.

Peltomäki P. Role of DNA mismatch repair defects in the pathogenesis of human cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1174–1179.

Hampel H, Stephens JA, Pukkala E, et al. Cancer risk in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome: later age of onset. Gastroenterology 2005;129:415–421.

Aaltonen LA, Salovaara R, Kristo P, et al. Incidence of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and the feasibility of molecular screening for the disease. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1481–1487.

Salovaara R, Loukola A, Kristo P, et al. Population-based molecular detection of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2193–2200.

Wahlberg SS, Schmeits J, Thomas G, et al. Evaluation of microsatellite instability and immunohistochemistry for the prediction of germ-line MSH2 and MLH1 mutations in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer families. Cancer Res 2002;62:3485–3492.

Liu T, Tannergård P, Hackman P, et al. Missense mutations in hMLH1 associated with colorectal cancer. Hum Genet 1999;105:437–441.

Jover R, Payá A, Alenda C, et al. Defective mismatch-repair colorectal cancer: clinicopathologic characteristics and usefulness of immunohistochemical analysis for diagnosis. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;122:389–394.

Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Leontovich O, et al. Immunohistochemistry versus microsatellite instability testing in phenotyping colorectal tumors. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1043–1048.

Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:261–268.

Chung DC, Rustgi AK. The hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome: genetics and clinical implications. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:560–570.

Beamer LC, Grant ML, Espenschied CR, et al. Reflex immunohistochemistry and microsatellite instability testing of colorectal tumors for Lynch syndrome among US cancer programs and follow-up of abnormal results. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1058–1063.

Cross DS, Rahm AK, Kauffman TL, et al.; CERGEN study team. Underutilization of Lynch syndrome screening in a multisite study of patients with colorectal cancer. Genet Med 2013;15:933–940.

Bellcross CA, Bedrosian SR, Daniels E, et al. Implementing screening for Lynch syndrome among patients with newly diagnosed colorectal cancer: summary of a public health/clinical collaborative meeting. Genet Med 2012;14:152–162.

Peres J. To screen or not to screen for Lynch syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1382–1384.

Hall MJ. Counterpoint: implementing population genetic screening for Lynch Syndrome among newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients–will the ends justify the means? J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2010;8:606–611.

Cohen SA. Current Lynch syndrome tumor screening practices: a survey of genetic counselors. J Genet Couns 2014;23:38–47.

Denzin N, Lincoln Y. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd edn. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2011.

Silverman D. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2010.

Creswell JW, Plano VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2007.

Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd edn. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2002.

Seidman I. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and Social Sciences. Teachers College Press: New York, 1991.

Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2008;34:228–243.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procdures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2008.

Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, 2010.

Hampel H, Frankel WL, Martin E, et al. Feasibility of screening for Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5783–5788.

Mvundura M, Grosse SD, Hampel H, Palomaki GE. The cost-effectiveness of genetic testing strategies for Lynch syndrome among newly diagnosed patients with colorectal cancer. Genet Med 2010;12:93–104.

Ladabaum U, Wang G, Terdiman J, et al. Strategies to identify the Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:69–79.

Gudgeon JM, Williams JL, Burt RW, Samowitz WS, Snow GL, Williams MS. Lynch syndrome screening implementation: business analysis by a healthcare system. Am J Manag Care 2011;17:e288–e300.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported through a grant by the National Institute of Health: 5R01CA140377 (K.A.B.G.).The authors thank Jill Pope for editorial support and Robin Daily and Elizabeth Sheeley for administrative assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Schneider, J., Davis, J., Kauffman, T. et al. Stakeholder perspectives on implementing a universal Lynch syndrome screening program: a qualitative study of early barriers and facilitators. Genet Med 18, 152–161 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.43

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.43

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Healthcare professionals’ perspectives on implementation of universal tumor DNA testing in ovarian cancer patients: multidisciplinary focus groups

Familial Cancer (2023)

-

Identifying patients with Lynch syndrome using a universal tumor screening program in an integrated healthcare system

Hereditary Cancer in Clinical Practice (2022)

-

Stakeholders’ views of integrating universal tumour screening and genetic testing for colorectal and endometrial cancer into routine oncology

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

-

Progress of equalizing basic public health services in Southwest China--- health education delivery in primary healthcare sectors

BMC Health Services Research (2020)

-

Effective Identification of Lynch Syndrome in Gastroenterology Practice

Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology (2019)