Abstract

Purpose:

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multiple basal cell carcinomas, jaw cysts, palmar/plantar pits, spine and rib anomalies, and falx cerebri calcification. Current diagnostic criteria are suboptimal when applied to pediatric populations, as most common symptoms often do not begin to appear until teenage years.

Methods:

We studied minor and major clinical features in 30 children/teenagers and compared the findings with 75 adults from 26 families with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome.

Results:

Fifty percent of children/teenagers and 82% of adults had at least one basal cell carcinoma. Jaw cysts occurred in 60% of children/teenagers and 81% of adults. Palmar/plantar pits were the most frequent feature seen in affected individuals at all ages. Macrocephaly was seen in 50% of affected and 8% of unaffected children/teenagers. Frontal bossing, hypertelorism, Sprengel deformity, pectus deformity, and cleft lip/palate were seen among affected children/teenagers but not among their unaffected siblings. Falx calcification, the most frequent radiological feature, was present in 37% of individuals <20 and 79% of those >20 years.

Conclusion:

We report clinical and radiological manifestations of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome in children/teenagers, many of whom lacked major features such as basal cell carcinomas, jaw cysts, and falx calcification. Evaluations for palmar/plantar pits, craniofacial features, and radiological manifestations permit early diagnosis and optimum surveillance.

Genet Med 2013:15(1):79–83

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in PTCH, the tumor suppressor and human homologue of the Drosophila patched gene.1,2 Also known as Gorlin Syndrome and basal cell nevus syndrome (OMIM no. 109400), the syndrome is characterized primarily by basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts of the jaw, palmar/plantar pits, ectopic calcification of the falx cerebri, macrocephaly, and skeletal abnormalities such as bifid ribs, wedge-shaped vertebrae, and a short fourth metacarpal.3,4,5,6,7,8 The estimated prevalence of the syndrome is 1 per 30,000 individuals.9

Essentially complete penetrance has been observed with the syndrome, but expressivity is highly variable within and across families.10 The high degree of variation in expressivity of clinical features in NBCCS patients has been reported by numerous researchers.5,11,12,13,14 Established diagnostic criteria5,6,14 are informative when evaluating adults; however, children often do not display the most common symptoms until their teenage years. The presence of BCC as a diagnostic criterion15 is suboptimal in the pediatric population.14 Lo Muzio et al.3 noted that BCCs usually do not proliferate until puberty, and other signs such as jaw cysts are detected only after the clinical situation has progressed. Amlashi et al.16 reported children presenting with medulloblastomas before developing BCC.

We have earlier reported on the characteristic clinical and radiological findings of NBCCS in a population consisting mainly of adults.5,14 The aim of this study was to describe the prevalence of the clinical features of NBCCS in a young population.

Materials and Methods

Patients were recruited at the National Institutes of Health between 1985 and 1994 under a National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases protocol. The study was approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board and appropriate consent was obtained for each patient. Twenty-six families were studied, encompassing 30 affected children and teenagers and 75 affected adults. A child/teenager was defined as anyone younger than the age of 20 years.

Participants were given detailed dysmorphology, dermatological, and radiographic examinations; however, a complete panel of examinations was not performed on every study participant due to logistical constraints. Radiography included the skull, ribs, spine, hands, feet, long bones, and pelvis. Dental evaluation included a panorex film. Brain imaging was obtained with magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scans. Females underwent a pelvic ultrasound.

A diagnosis of NBCCS was established if two major or one major and two minor criteria were satisfied. Major diagnostic criteria included more than two BCCs or at least one before the age of 20, keratocysts of the jaw, palmar/plantar pits, lamellar calcification of falx cerebri, rib anomalies, ovarian fibromas, medulloblastoma, and flame-shaped lucencies of the phalanges. Minor criteria included spina bifida occulta and other vertebral anomalies, brachymetacarpaly, hypertelorism/telecanthus, and frontal bossing.5 An affected first-degree relative was considered a major criterion of NBCCS.5 Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 6.1 (IBM, Armonk, NY) for Windows. A cross-table analysis of the clinical features in affected and unaffected individuals in both the <20 and >20 years age groups was performed, in addition to calculating means for continuous variables. Statistical significance (using the Pearson test for categorical variables and the t-test for continuous variables) was demonstrated when a P value of <0.05 was obtained. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to evaluate the probability of onset at different ages for several clinical findings.

Results

We studied 26 families with 30 affected children and teenagers ranging in age from 4 months to 19 years (mean 11.3 years; male to female ratio 1:1). Twenty-five unaffected siblings from these families were also evaluated as a comparison population. Their ages ranged from 5.5 to 19.5 years (mean 12.1 years; male to female ratio 1:1.8). Table 1 provides a summary of the demographic characteristics of the study population.

As compared with the affected adults (ranging in age from 20 to 87 years), not surprisingly, affected children and teenagers displayed lower frequencies of the major clinical features. When the population studied was segregated between those <20 years and ≥20 years of age, 50% of children and teenagers (<20 years) and 82% of those ≥20 years had one or more BCCs. Jaw cysts occurred in 60% of children/teenagers and 81% of adults, with the number of cysts ranging from 1 to 6 (median 3) and 1 to 28 (median 5), respectively. Kaplan–Meier analysis of the entire NBCC population (including Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic families) studied indicated that 50% of individuals developed their first BCC by age 21.5 years and their first jaw cyst by 15 years. Palmar and plantar pits ( Figure 1 ) were seen at the same high frequency in both children/teenagers and adults (90 and 86%, respectively). The data are summarized in Figure 2 .

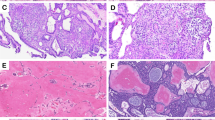

As compared with their unaffected siblings, there was a statistically significant difference in the presence of craniofacial abnormalities such as macrocephaly, frontal bossing, strabismus, and palate abnormalities (excluding cleft palate) in affected children/teenagers. Hypertelorism and synophrys were observed in 38% of affected children/teenagers and 15 and 13%, respectively, in unaffected siblings. This finding approached, but did not meet, statistical significance (P = 0.08). ( Figures 1 and 3 illustrate some of the characteristic features of juvenile NBCCS in affected young individuals.) Radiological features that were observed to occur in a significantly higher frequency in affected children and teenagers included bridged sella, ectopic calcification of the falx, and bifid ribs. Sprengel deformities were also observed more frequently in affected children and teenagers ( Table 2 ).

Craniofacial manifestations of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (NBCCS). (a) Macrocephaly, synophrys, epicanthic folds, basal cell nevi, and (b) micrognathia in a young girl with juvenile NBCCS. The patient provided assent for the use of her photographs in this article, and her mother provided consent.

Some features were only observed in affected children and teenagers. These include ectopic calcification of the tentorium cerebellum, fused or splayed ribs, hemivertebrae, fusion of the vertebral bodies, flame-shaped lucencies, modeling defects of the hands and feet, and pectus deformities ( Table 2 ). Interestingly, the frequencies of scoliosis, cervical ribs, absence of ribs or rudimentary ribs, spina bifida occulta, or short fourth metacarpal were not increased in affected individuals as compared with their unaffected siblings. Table 2 provides a more complete overview of the data.

Discussion

We studied minor and major clinical features of NBCCS in 30 children/teenagers and 75 adults with NBCCS from 26 families in an attempt to improve the current diagnostic criteria in the pediatric population. We found that many affected children/teenagers lacked major features such as BCCs, jaw cysts, and falx calcification. The presence of palmar/plantar pits was a useful diagnostic feature as it was displayed at the same high frequency in children/teenagers and adults. Other important manifestations in the affected children and teenagers include palatal abnormalities, macrocephaly, and bridged sella, all of which were prevalent in at least 50% of young patients.

Molecular testing was performed earlier in 199817 in a subset of this cohort by di-deoxy fingerprinting, and mutations were identified in 10 of 15 families comprising of 37 individuals. Mutations were identified in only eight children, thus making any statistical conclusions impossible for this study. This testing was designed as a screening tool for mutations and many may have been missed by this method.

Most NBCCS diagnoses in children are made on the basis of clinical diagnostic criteria,5 even with the clinical availability of PTCH mutation analysis. Although PTCH has been identified as the gene causing NBCCS and mutations in PTCH can confirm a clinical diagnosis, molecular genetic testing has not been able to detect mutations in all affected individuals.17,18,19,20,21 Bale et al.17,22 found that families with a history of multiple NBCCS features were more likely to have a detectable mutation; nevertheless, mutations were detected in only 40% of families tested in the study.22 This failure to detect a mutation is likely due to the limitations of available technology, as well as the high rate of somatic mutations, rather than the presence of other causative genes. More recent use of technologies such as multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification and competitive genomic hybridization array help identify single or multiple exon deletions in PTCH that were previously undetectable by direct sequencing of exons and splice junctions.17,23

Jones et al.24 recently evaluated 202 individuals with Gorlin syndrome and reported PTCH mutations in 61% of individuals tested. They determined that there was no genotype/phenotype correlation, and also found that the age at which BCCs first develop and the total number of BCCs had no association with the presence or absence of a mutation, or the mutation type. Although it can be argued that the combination of detailed physical and radiographical examination in children suspected of NBCCS approximates the cost of DNA testing, in reality, the reported detection frequency falls between 50 and 85%.25 It has been shown that one of the reasons for failure of genetic testing is somatic mosaicism. It is estimated that ~20–30% of NBCCS cases are de novo, and some of these will result in somatic mosaicism.24 The stage of development in which the somatic mutation occurred will affect the proportion of affected cells, and a blood test for mutation analysis therefore may not detect such mutations.24 In addition, some failures may be caused by clinical misdiagnoses.

We believe that molecular testing is a valuable part of an NBCCS diagnosis; however, many patients still face barriers to molecular testing for various reasons including cost and limitations of insurance coverage. Therefore, thorough clinical diagnostic criteria are critical. Our study compared clinical features in affected individuals with their unaffected siblings and provides useful guidelines on the utility of clinical evaluations in the diagnosis of NBCCS.

Kimonis et al.5 have noted that the most prevalent clinical features in NBCCS, BCCs and jaw cysts, typically do not develop until the teenage years, and therefore it is difficult to diagnose affected children using the standard criteria. Palmar and plantar pits, in conjunction with radiological and other clinical data, are more indicative of the disorder than BCCs in young individuals.14 Recognized craniofacial abnormalities such as macrocephaly (50%), frontal bossing (45%), palatal abnormalities (53%), strabismus (25%), hypertelorism and synophrys (38%), and skeletal findings such as pectus and Sprengel deformity may suggest a diagnosis of NBCCS. Important radiological signs include ectopic calcification of the falx with an increasing incidence over time, bridged sella, bifid ribs, hemivertebrae, fusion of the vertebral bodies, flame-shaped lucencies of the hands and feet, and modeling defects. Although not statistically significant in our study due to small sample size, many of these features are notable in that they were present only in affected teenagers. Their occurrence therefore lends suspicion to a diagnosis of NBCCS.

To maximize these diagnostic indicators, young individuals at risk should undergo careful clinical evaluations for palmar/plantar pits and suggestive dysmorphic features, as well as baseline radiological examinations, particularly of the skull, chest and ribs, spine, and hands and feet. Regular dental surveillance, including imaging of the jaw, should be obtained annually in at-risk individuals to identify jaw cysts. Of note, care must be taken to avoid overexposure to radiation, which has been shown to cause increased tumor growth in affected individuals.5,16,26 Magnetic resonance imaging is theoretically a superior surveillance tool to panorex X-rays; however, due to the higher cost of magnetic resonance imaging and the need for sedation in young children, panorex may well be a better first-line screen and magnetic resonance imaging can be used to further evaluate internal composition and structure of observed lesions.27,28 Exposure to sunlight should be minimized,29 and regular dermatological surveys should begin in childhood.

This study reports the varied clinical and radiological manifestations of NBCCS in children and teenagers. In the absence of major features such as BCCs, jaw cysts, or falx calcification, screening for palmar/plantar pits, craniofacial features, specific radiological manifestations, and molecular testing of the PTCH gene facilitates the diagnosis in children and teenagers. Increased appreciation of the prevalence and likely predictors of NBCCS are important, either as an alternative or prescreening for molecular testing. Improved diagnostic indicators are especially important in children/teenagers because of the potential of avoiding complications of BCC.

Disclosure

S.J.B. is an employee and stockholder in GeneDx, which provides genetic testing for Gorlin syndrome. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Hahn H, Wicking C, Zaphiropoulous PG, et al. Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell 1996;85:841–851.

Johnsona RL, Rothman AL, Xie J, et al. Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science 1996;272: 1668–1671.

Lo Muzio L, Nocini P, Bucci P, Pannone G, Consolo U, Procaccini M . Early diagnosis of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130:669–674.

R Yang X, Pfeiffer RM, Goldstein AM . Influence of glutathione- S-transferase (GSTM1, GSTP1, GSTT1) and cytochrome p450 (CYP1A1, CYP2D6) polymorphisms on numbers of basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) in families with the naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Med Genet 2006;43:e16.

Kimonis VE, Goldstein AM, Pastakia B, et al. Clinical manifestations in 105 persons with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1997;69:299–308.

Evans DG, Ladusans EJ, Rimmer S, Burnell LD, Thakker N, Farndon PA . Complications of the naevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: results of a population based study. J Med Genet 1993;30:460–464.

Howell JB, Caro MR . The basal-cell nevus: its relationship to multiple cutaneous cancers and associated anomalies of development. AMA Arch Derm 1959;79:67–77; discussion 77.

Gorlin RJ, Goltz RW . Multiple nevoid basal-cell epithelioma, jaw cysts and bifid rib. A syndrome. N Engl J Med 1960;262:908–912.

Evans DG, Howard E, Giblin C, et al. Birth incidence and prevalence of tumor-prone syndromes: estimates from a UK family genetic register service. Am J Med Genet A 2010;152A:327–332.

Gorlin RJ . Nevoid basal cell carcinoma (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med 2004;6:530–539.

Veenstra-Knol HE, Scheewe JH, van der Vlist GJ, van Doorn ME, Ausems MG . Early recognition of basal cell naevus syndrome. Eur J Pediatr 2005;164:126–130.

Campbell RM, Mader RD, Dufresne RG, Jr . Meningiomas after medulloblastoma irradiation treatment in a patient with basal cell nevus syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;53(5 suppl 1):S256–S259.

Pastorino L, Cusano R, Baldo C, et al. Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome in infants: improving diagnosis. Child Care Health Dev 2005;31:351–354.

Kimonis VE, Mehta SG, Digiovanna JJ, Bale SJ, Pastakia B . Radiological features in 82 patients with nevoid basal cell carcinoma (NBCC or Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med 2004;6:495–502.

Chiritescu E, Maloney ME . Acrochordons as a presenting sign of nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:789–794.

Amlashi SF, Riffaud L, Brassier G, Morandi X . Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: relation with desmoplastic medulloblastoma in infancy. A population-based study and review of the literature. Cancer 2003;98: 618–624.

Bale SJ, Falk RT, Rogers GR . Patching together the genetics of Gorlin syndrome. J Cutan Med Surg 1998;3:31–34.

Wicking C, Shanley S, Smyth I, et al. Most germ-line mutations in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome lead to a premature termination of the patched protein, and no genotype-phenotype correlations are evident. Am J Hum Genet 1997;60:21–26.

Fujii K, Kohno Y, Sugita K, et al. Mutations in the human homologue of Drosophila patched in Japanese nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients. Hum Mutat 2003;21:451–452.

Boutet N, Bignon YJ, Drouin-Garraud V, et al. Spectrum of PTCH1 mutations in French patients with Gorlin syndrome. J Invest Dermatol 2003;121: 478–481.

Chidambaram A, Goldstein AM, Gailani MR, et al. Mutations in the human homologue of the Drosophila patched gene in Caucasian and African-American nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome patients. Cancer Res 1996;56:4599–4601.

Klein RD, Dykas DJ, Bale AE . Clinical testing for the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome in a DNA diagnostic laboratory. Genet Med 2005; 7:611–619.

Bale S, Benhamed S . gorlin Syndrome: a Large Proportion of Previously “Missing” Mutations Are Large ptch Deletions. American Society of Human Genetics: Philadelphia, PA, 2008.

Jones EA, Sajid MI, Shenton A, Evans DG . Basal cell carcinomas in gorlin syndrome: a review of 202 patients. J Skin Cancer 2011;2011:217378.

Evans DG, Farndon PA. Nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. In: GeneReviews at GeneTests Medical Genetics Information Resource (database online). University of Washington: Seattle, Washington, 1997–2012. http://www.genetests.org. Accessed 15 January 2012.

O’Malley S, Weitman D, Olding M, Sekhar L . Multiple neoplasms following craniospinal irradiation for medulloblastoma in a patient with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Case report. J Neurosurg 1997;86:286–288.

Janse van Rensburg L, Nortje CJ, Thompson I . Correlating imaging and histopathology of an odontogenic keratocyst in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1997;26:195–199.

Palacios E, Serou M, Restrepo S, Rojas R . Odontogenic keratocysts in nevoid basal cell carcinoma (Gorlin’s) syndrome: CT and MRI evaluation. Ear Nose Throat J 2004;83:40–42.

Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, DiGiovanna JJ . Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;29:34–41.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health. We thank the participating patients, families, and their physicians whose contributions have made this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kimonis, V., Singh, K., Zhong, R. et al. Clinical and radiological features in young individuals with nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Genet Med 15, 79–83 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2012.96

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2012.96

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinical, radiographic, pathological and inherited characteristics of odontogenic keratocyst in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: a study in three Chilean families

Oral Radiology (2023)

-

Co-occurrence of mutations in FOXP1 and PTCH1 in a girl with extreme megalencephaly, callosal dysgenesis and profound intellectual disability

Journal of Human Genetics (2018)

-

Male fertility and skin diseases

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2016)