Abstract

Purpose: Interferon regulatory factor 6 encodes a member of the IRF family of transcription factors. Mutations in interferon regulatory factor 6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndrome, two related orofacial clefting disorders. Here, we compared and contrasted the frequency and distribution of exonic mutations in interferon regulatory factor 6 between two large geographically distinct collections of families with Van der Woude and between one collection of families with popliteal pterygium syndrome.

Methods: We performed direct sequence analysis of interferon regulatory factor 6 exons on samples from three collections, two with Van der Woude and one with popliteal pterygium syndrome.

Results: We identified mutations in interferon regulatory factor 6 exons in 68% of families in both Van der Woude collections and in 97% of families with popliteal pterygium syndrome. In sum, 106 novel disease-causing variants were found. The distribution of mutations in the interferon regulatory factor 6 exons in each collection was not random; exons 3, 4, 7, and 9 accounted for 80%. In the Van der Woude collections, the mutations were evenly divided between protein truncation and missense, whereas most mutations identified in the popliteal pterygium syndrome collection were missense. Further, the missense mutations associated with popliteal pterygium syndrome were localized significantly to exon 4, at residues that are predicted to bind directly to DNA.

Conclusion: The nonrandom distribution of mutations in the interferon regulatory factor 6 exons suggests a two-tier approach for efficient mutation screens for interferon regulatory factor 6. The type and distribution of mutations are consistent with the hypothesis that Van der Woude is caused by haploinsufficiency of interferon regulatory factor 6. On the other hand, the distribution of popliteal pterygium syndrome-associated mutations suggests a different, though not mutually exclusive, effect on interferon regulatory factor 6 function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The prevalence of orofacial clefting varies from 1 in 500 to 1 in 2500 births, depending on geographic origin, race, and socioeconomic background.1–4 About 70% of orofacial clefts occur as isolated cases and the remainder can be attributed to chromosomal abnormalities, maternal exposure to teratogens, and syndromes where the phenotype includes other developmental or morphological abnormalities.5

Van der Woude syndrome (VWS, OMIM 119300) is one of the most common oral cleft syndromes and accounts for ∼2% of all cleft lip (CL) and palate cases. VWS is clinically characterized by congenital lower lip pits, CL, CL with or without cleft palate (CLP), cleft palate only (CPO), and hypodontia. Other, less common features include syndactyly of the fingers, syngnathia, and ankyloblepheron.6 VWS is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with high penetrance (96.7%) but variable expression.7 The phenotype of the lower lip varies from a single barely evident depression to bilateral fistulae of the lower lip, and the orofacial cleft varies from a bifid uvula to a complete CL and palate.6 These facial anomalies are also seen in individuals with popliteal pterygium syndrome (PPS, OMIM 119500), a disorder that includes other physical signs, including bilateral popliteal webs, syndactyly, genital anomalies, ankyloblepharon, oral synechiae, and nail abnormalities.

The genetic localization for VWS was assigned by linkage analysis8 and through chromosome abnormalities involving chromosome 1q32-q41.9–11 Overall, there is little evidence for genetic heterogeneity, although evidence for a second potential VWS locus was reported for chromosome 1p36-p32.12 Sertie et al.13 suggested that a gene at chromosome 17p11.2-p11.1, together with the VWS gene, enhances the probability of CP in an individual carrying two risk alleles.

Previously, we described a nonsense mutation in the interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene in the affected sib of two monozygotic twins discordant for VWS, suggesting IRF6 as a candidate for VWS.14 This hypothesis was confirmed in the same study by the detection of IRF6 mutations in 45 additional unrelated families with VWS. In addition, a unique set of mutations in IRF6 was discovered in 13 families with PPS, demonstrating that VWS and PPS are allelic, as previously suggested.15 Subsequently, mutations in IRF6 were identified in 56 additional families with VWS and three with PPS.16–36

The objectives of this article are to determine the prevalence and distribution of mutations in the exons of IRF6 in families with VWS and PPS. We describe the complete sequence analysis of IRF6 exons in two large VWS collections and one PPS collection. Despite geographical diversity between the two VWS collections, the likelihood of finding an exonic mutation in IRF6 was similar as was their distribution. The type and distribution in location of PPS mutations differ significantly from the VWS mutations but are not mutually exclusive. The results provide the foundation to identify genotype–phenotype correlations in disorders caused by mutations in IRF6 and to determine structure–function relationships in the IRF family of transcription factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Populations

Each proband was examined by a clinical geneticist or genetic counselor. Two collections of unrelated families affected with VWS were obtained, one from Brazil (N = 110) and one of mixed geographic origin (N = 197). The collection from Brazil has not been described previously. The geographic origin of the mixed collection is primarily northern Europe and includes families from the United States (152), Belgium (31), Germany (7), United Kingdom (3), Thailand (2), Philippines (1), and Brazil (1). Many of these families (175) were described previously14,16,21,23 and were included in this study to provide a comprehensive analysis of the complete collections of families with VWS and PPS. Diagnostic criteria for individuals to be considered affected with VWS included CLP or CPO, and at least one affected individual in the family with an anomaly in the lower lip, generally bilateral pits.

In addition, a single collection of unrelated families affected with PPS (N = 37) was obtained. The geographic origin of the PPS families was mainly northern Europe, but included one family from Brazil. Diagnostic criteria for individuals affected with PPS included the VWS criteria listed above along with the presence of bilateral popliteal webs or a combination of syndactyly, genital anomalies, ankyloblepharon, oral synechiae, and nail abnormalities from one or more members in a family. Sample collection and processing were performed as described previously.37 We obtained written informed consent from all subjects and approval for all protocols from the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Iowa, the University of Manchester, the University of São Paulo State and CONEP/Brazil, the Université catholique de Louvain, and Zentrum fur Gynäkologische Endokrinologie, Reproduktionsmedizin und Humangenetik, Regensburg, Germany.

Polymerase chain reaction

Exons 1–8 and part of exon 9 of IRF6 were amplified by standard PCR using the primers shown in Table 1. PCR experiments for exons 1–8 were performed in a 10 μL total volume mixture containing 20 ng of genomic DNA, 0.5 μM each primer, 200 μM dNTPs, 0.25% DMSO, 0.2 unit Bio-X-Act Taq polymerase (Bioline, Reno, NV), and 1× PCR buffer supplied by the manufacturer. PCR conditions are as follows: initial denaturation 3 minutes at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 57°C for 30 seconds, elongation at 68°C for 1 minute, and final elongation at 68°C for 3 minutes. Conditions for PCR experiments for exon 9 were performed as above except 0.3 μM each primer, Biolase Taq polymerase (Bioline) and initial denaturation 5 minutes at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 seconds, annealing at 57°C for 45 seconds, elongation at 72°C for 45 seconds, and final elongation at 72°C for 3 minutes.

DNA sequence analysis

The amplified products were sequenced directly using Big Dye sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA) as recommended. Sequence samples were purified with magnetic beads and run on an automated sequencer model ABI Prism 3700 (Perkin-Elmer). DNA sequences were aligned and analyzed using the software PHRED/PHRAP/CONSED.38 Reference sequences for IRF6 cDNA, genomic DNA, and protein were NM_006147.2, RP3-434o14 (Genbank AL022398), and NP_006138, respectively. DNA sequence variants were confirmed by sequencing the opposite strand in the proband and, if possible, in at least one other affected family member. To identify nonetiologic polymorphisms, DNA sequence analysis was performed for all IRF6 exons on a minimum of 200 unaffected control samples derived from geographically diverse populations.39

Splice site prediction

The effect of mutations on splicing activity was modeled using Genscan.40 Wild-type and mutant sequences were compared using default settings.

Statistical analysis

Frequency tables showed population-specific frequency distribution of mutations across the nine exons. The 2 × 9 tables were analyzed using the χ2 statistic or Fisher exact test when appropriate (e.g., when the expected cell count was <5 for at least 20% of the cells).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Prevalence of exonic mutations in IRF6

DNA samples were derived from two distinct VWS collections, one from Brazil (N = 110) and one of mixed origin that was primarily from northern Europe (N = 197). In addition, we screened a PPS collection of mixed geographical origin (N = 37). The mutation screen used in this study was modified slightly from the screen described previously by Kondo et al.14 PCR primers for exon 9 were redesigned (Table 1), and the new primers amplified this region more robustly and generated DNA sequence more reliably. In the VWS collections, we identified IRF6 exonic mutations in 77 of 110 (71%) families from Brazil and identified 132 of 197 (67%) families from the mixed collection (Table 2). The likelihoods for finding exonic mutations in IRF6 between these two diverse VWS collections are not statistically different (P = 0.61) and are consistent with common mutation mechanisms.

Mutations located in the exons of IRF6 have been identified for only 68% of families with VWS analyzed to date. Several possibilities exist to explain the remaining 32%. IRF6 may have gross deletions that are not detected by our DNA sequencing strategy. Etiologic mutations may exist within IRF6, but located outside the exons. Finally, some proportion of the remaining families may be due to mutations located in some other gene. To date, deletions have been found in only six families with VWS.10,11,24,29 In general, these have been large deletions and further studies with more sensitive methods are needed to screen for kilobase-sized deletions. Despite the lack of linkage evidence for locus heterogeneity in VWS, it is also possible that VWS-causing mutations may be found in other genes. For example, a polygenic mechanism might contribute to some cases of VWS but would be difficult to detect in the previous linkage studies. The number and size of families that lack an exonic mutation in IRF6 should be sufficient to test for genetic heterogeneity in the VWS collection.

In the PPS collection, we identified exonic mutations in IRF6 in 36 of 37 unrelated families, demonstrating that IRF6 is the principal gene involved in this disorder. When combined with the VWS mutation studies, IRF6 exonic mutations were identified in 249 unrelated families, representing 170 total and 106 novel alleles (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/A713). None of these mutations was observed in our control samples (see Materials and Methods section), suggesting that they are etiologic. However, we identified 41 DNA sequence variants from our mutation screen, including four nonsynonymous polymorphisms, Asp19Asn, Ala61Pro, Thr224Ser, and Val274Ile (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/A714). As these variants were detected in control cases, they are not etiologic for VWS or PPS. However, Val274Ile is highly associated with isolated CL and palate,41–46 and functional studies must be performed to test Val274Ile and other alleles as potential susceptibility alleles.

Nonrandom distribution of IRF6 exonic mutations in VWS collections

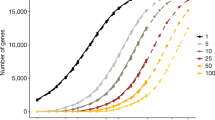

The distribution of all exonic mutations in IRF6 in the VWS collections is not random (P < 0.0001; Table 3, row A). More mutations were located in exons 3, 4, 7, and 9 than expected, suggesting a multitier approach for mutation screening of IRF6 in VWS cases. This pattern was observed in both the Brazilian (Fig. 1A) and mixed origin (Fig. 1B) VWS collections, suggesting that the mutation mechanisms for IRF6 are independent of origin of the population.

Distribution of exonic mutations in IRF6. Each panel shows the genomic structure for IRF6. Exons (rectangles) are color coded as untranslated (gray), encode DNA binding domain (yellow), or encode the protein binding domain (green). The introns (space between exons) are not drawn to scale. The relative position of protein truncation mutations (red triangle), missense mutations (blue triangle), and splicing mutations (black triangle) is shown. Below each genomic structure is the distribution of missense (blue; includes in-frame deletions and insertions), protein truncation (red; includes nonsense, frameshift, and large deletions), and splicing (white) mutations in each exon for each population. (A) Mutations found in VWS collection from Brazil. (B) Mutations found in VWS collection from mixed geographic origin. (C) Mutations found in PPS collection.

Protein truncation mutations (nonsense and frameshifts) were observed in all exons before the endogenous stop codon in exon 9. Interestingly, we identified point mutations in six families in exons 1 and 2 that create new start codons in the 5′ untranslated region. These new start sites should not make IRF6 protein as they are in the wrong reading frame, but may not prevent initiation at the native site. The protein truncation mutations are evenly distributed across the gene, except for exon 9 (Table 3, row B). The spike in protein truncation mutations in exon 9 seems to be due to 1 of 5 mutational hotspots in IRF6 (see later). Overall, the high prevalence of protein truncation mutations in families with VWS (80 of 207), in addition to the six known IRF6 deletions,10,11,14,24,29 provides further support that VWS can be caused by haploinsufficiency of IRF6.

Nearly all of the 117 mutations that do not truncate the protein (missense and in-frame insertions and deletions) are localized to regions encoding the DNA binding domain (64 families) and the protein binding domain (45 families). The significant over-representation of missense mutations in the DNA binding (exons 3 and 4) and protein binding (exons 7–9) domains (Table 3, row C) reinforces the importance of these domains for IRF6 function.

Nonrandom distribution of IRF6 exonic mutations in the PPS collection

The location of mutations identified in families with PPS is nonrandom (Table 3, row E). In 34 of 36 families with PPS, the mutation is located in exons 3, 4, or 9 (Fig. 1C). Like VWS, these observations suggest a multitier approach for efficient mutation screens for PPS. However, the distribution of mutations among the exons for the PPS collection differs significantly from the VWS collections (P < 0.0001; Table 3, row A vs. E). Another difference is the low frequency of protein truncation mutations in the PPS versus VWS collections (5/36 vs. 80/207; P = 0.036) and the high frequency of missense mutations in exon 4 in the PPS versus VWS collections (26/36 vs. 42/207; P < 0.0001). In addition, the distribution of missense mutations within the DNA binding domain (exons 3 and 4) is nonrandom for the PPS collection (Fig. 2). Specifically, the missense mutations in the PPS collection are more likely to be located at residues that are predicted to contact DNA, when compared with random chance (P ≤ 7 × 10−9) and with missense mutations in the VWS collection (P ≤ 1 × 10−6). On the basis of the significant differences in the frequency of the type of mutation and distribution in location of mutations found in the PPS versus the VWS collections, we conclude that the PPS-associated mutations affect IRF6 function differently than VWS-associated mutations.

Distribution of missense mutations in the DNA binding domain of IRF6. Mutations were identified in families with VWS (closed circles) and families with PPS (open circles). Amino acids predicted to directly contact DNA (underline) are based on crystal structure of IRF1 (see text). The expected number of mutations that contact DNA is based on the ratio of 17 amino acids that are predicted to contact the DNA (underlined, see text) out of 120 total amino acids in the DNA binding domain.

How might VWS- and PPS-associated mutations affect IRF6 function differently? The identification of six large deletions of IRF6,10,11,24,29 along with the high frequency of protein truncation mutations, demonstrates that VWS can be caused by loss of function of IRF6. For families with PPS, we hypothesized previously that mutations have a dominant negative effect on IRF6.14 The rationale for this hypothesis is that the Arg84Cys and Arg84His mutations abrogate DNA binding47 but are not predicted to affect protein binding. Consequently, protein dimers are predicted to form between a wild-type isoform and the Arg84Cys and Arg84His isoform, but such a dimer will not be able to bind DNA. This model is supported by two main observations. First, in a previous study, mice heterozygous for a PPS-associated Irf6 allele (Arg84Cys) had a more severe and more penetrant phenotype than mice that were heterozygous for a loss of function allele.47,48 Second, in this study, we observed that mutations identified in families with PPS are much more likely to be missense mutations than in families with VWS, and that mutations are more likely to be located at residues that are predicted to directly contact the DNA. Such mutations are more likely to affect DNA binding without affecting protein stability or protein interaction. The most common examples of this class of mutations are Arg84Cys and Arg84His (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/A713).

However, these data do not fully support a simple model whereby VWS is caused by IRF6 loss-of-function mutations and PPS is caused by IRF6 dominant negative mutations. Foremost, the same mutations were identified in patients with VWS and with PPS. For example, we identified missense mutations at Arg84 in seven families diagnosed with VWS and 21 with PPS (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/A713). The mutations Arg84Cys and Arg84His were found in five families diagnosed with VWS. Moreover, individuals with VWS and PPS have been diagnosed in the same family.21 These data suggest that although the association between the Arg84Cys and Arg84His mutations and PPS is strong, it is not absolute. In sum, the data are most consistent with the model that VWS is most likely caused by loss (or partial loss)-of-function mutations, but can also be caused by dominant negative mutations, and that PPS is most likely caused by dominant negative mutations but can also be caused by loss (or partial loss) of function mutations. The range of phenotypes for VWS and PPS, including their overlap, suggests the likely contributions of stochastic events and genetic modifiers13 for IRF6-related disorders.

Three other observations are relevant to the effect of VWS and PPS mutations on IRF6 function. First, we identified a novel missense change at Arg84, Arg84Pro, in two families where affected individuals were diagnosed with VWS. In addition, Item et al.22 identified an Arg84Gly mutation in a family where both affected individuals were diagnosed with VWS. The Arg84Pro and Arg84Gly mutations challenge the dominant negative hypothesis, because this residue is predicted to contact the DNA but these mutations are only found in individuals with VWS. However, the residue Arg84 is located in the middle of helix 3 in IRF6. The amino acids proline and glycine are known to disrupt alpha helices.49 Consequently, the Arg84Pro and Arg84Gly mutations are predicted to disrupt the secondary and/or tertiary structure of IRF6, whereas Arg84Cys and Arg84His would not. Thus, we hypothesize that the Arg84Pro and Arg84Gly alleles cause complete loss of IRF6 function and result in VWS through haploinsufficiency of IRF6. Further biochemical and molecular studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Second, the splicing mutations at the 5′ splice site of intron 3 and the protein truncation mutations in exon 9 also challenge the dominant negative hypothesis for mutations that cause PPS. To produce a dominant negative allele, a defective, but stable protein must be produced. We hypothesize that the splicing mutations at the 5′ splice site of intron 3 activate a cryptic splice site that produces a mutant IRF6 allele that is stable, but unable to bind DNA. To test this hypothesis, we used Genscan,40 a program that predicts splice sites, to model the effect of the four splicing mutations at intron 3. For the two mutations at the highly conserved position +1 of intron 3, Genscan analysis predicts the loss of the endogenous splice site and the use of a cryptic splice site in the middle of exon 3 (Fig. 3). Moreover, the cryptic splice site rejoins exon 4 in frame, but deletes 41 amino acids from the DNA binding region encoded in exon 3. Thus, these splicing mutations create a potentially stable protein with a mutation in the DNA binding domain and are consistent with the dominant negative model for PPS mutations. However, like the Arg84Cys and Arg84His mutations, these mutations do not always cause PPS, as one of these mutations was identified in a family with VWS. Also, for the other two splice mutations in intron 3 found in families with PPS, Genscan did not predict loss of the endogenous splice site (Fig. 3).

Cryptic splice site in exon 3 revealed by computer modeling. The wild type (wt) and mutant sequences for the 5′ splice site for intron 3 are shown below the consensus sequence. In the consensus, M represents A or C and r represents G or A. The panel below contains the output from GENESCAN and shows the cryptic splice site in exon 3 revealed by the mutation at the endogenous site.

Third, protein truncation mutations in exon 9 were identified in families with either VWS or PPS. Although the effect of these mutations on IRF6 function is not known, previous studies with the other members of the IRF family showed that the C terminus contains an autoinhibitory domain.50 Recently, we discovered that IRF6 binds to maspin, a tumor suppressor gene, and that the C terminus blocks this interaction.51 Additional molecular and biochemical studies are needed to understand the effects of the PPS-causing mutations in exon 9.

Source of exonic mutations in IRF6

To date, we identified IRF6 exonic mutations in 249 unrelated families and represent 170 different disease-causing alleles in IRF6. Thus, 68% of exonic mutations in IRF6 are private and represent a wide array of potential mutational mechanisms. However, we identified five apparent hotspots. Mutations in the codons for Arg6, Arg84, Arg250, Arg400, and Arg412 were identified in 6, 26, 11, 7, and 14 unrelated families, respectively. The codon sequence for each of these residues contains a CpG dinucleotide. In humans, approximately one third of germline mutations result from loss of the CpG dinucleotide, and 90% of those are consistent with a mutation mechanism of cytosine methylation and deamination.52 Similarly, in this report, 55 of 64 (86%) of the mutations in these CpG codons were consistent with the cytosine methylation/deamination mechanism.

This study shows that exonic mutations in IRF6 are found in 68% of families with VWS and nearly all families with PPS. A few percent of families with VWS are caused by microdeletions of IRF6. Although the majority of the mutations are private, the distributions of exonic mutations suggest that future mutation searches should focus on exons 3, 4, 7, and 9 for families with VWS and on exons 3, 4, and 9 for families with PPS. In addition, because the distribution of mutations is consistent between geographically distinct populations, this multitier approach for mutation discovery should be widely applicable. Further, the distributions of mutations in the VWS and PPS collections suggest some limited guides for risk assessment and suggest a molecular rationale for clinical heterogeneity caused by genetic variation in IRF6.

References

Cooper ME, Stone RA, Liu Y, Hu DN, Melnick M, Marazita ML . Descriptive epidemiology of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in Shanghai, China, from 1980 to 1989. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2000; 37: 274–280.

Murray JC, Daack-Hirsch S, Buetow KH, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic studies of cleft lip and palate in the Philippines. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 1997; 34: 7–10.

Tolarova MM, Cervenka J . Classification and birth prevalence of orofacial clefts. Am J Med Genet 1998; 75: 126–137.

Vanderas AP . Incidence of cleft lip, cleft palate, and cleft lip and palate among races: a review. Cleft Palate J 1987; 24: 216–225.

Jugessur A, Murray JC . Orofacial clefting: recent insights into a complex trait. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2005; 15: 270–278.

Gorlin RJ, Cohen AA, Hennekam RCM . Syndromes of the head and neck, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Cheney ML, Cheney WR, LeJeune FE Jr Familial incidence of labial pits. Am J Otolaryngol 1986; 7: 311–313.

Murray JC, Nishimura DY, Buetow KH, et al. Linkage of an autosomal dominant clefting syndrome (Van der Woude) to loci on chromosome 1q. Am J Hum Genet 1990; 46: 486–491.

Bocian M, Walker AP . Lip pits and deletion 1q32-q41. Am J Med Genet 1987; 26: 437–443.

Sander A, Schmelzle R, Murray J . Evidence for a microdeletion in 1q32-41 involving the gene responsible for Van der Woude syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 1994; 3: 575–578.

Schutte BC, Basart AM, Watanabe Y, et al. Microdeletions at chromosome bands 1q32-q41 as a cause of Van der Woude syndrome. Am J Med Genet 1999; 84: 145–150.

Koillinen H, Wong FK, Rautio J, et al. Mapping of the second locus for the Van der Woude syndrome to chromosome 1p34. Eur J Hum Genet 2001; 9: 747–752.

Sertie AL, Sousa AV, Steman S, Pavanello RC, Passos-Bueno MR . Linkage analysis in a large Brazilian family with van der Woude syndrome suggests the existence of a susceptibility locus for cleft palate at 17p11.2-11.1. Am J Hum Genet 1999; 65: 433–440.

Kondo S, Schutte BC, Richardson RJ, et al. Mutations in IRF6 cause Van der Woude and popliteal pterygium syndromes. Nat Genet 2002; 32: 285–289.

Lees MM, Winter RM, Malcolm S, Saal HM, Chitty L . Popliteal pterygium syndrome: a clinical study of three families and report of linkage to the Van der Woude syndrome locus on 1q32. J Med Genet 1999; 36: 888–892.

Brosch S, Baur M, Blin N, Reinert S, Pfister M . A novel IRF6 nonsense mutation (Y67X) in a German family with Van der Woude syndrome. Int J Mol Med 2007; 20: 85–89.

de Medeiros F, Hansen L, Mawlad E, et al. A novel mutation in IRF6 resulting in VWS-PPS spectrum disorder with renal aplasia. Am J Med Genet A 2008; 146: 1605–1608.

Del Frari B, Amort M, Janecke AR, Schutte BC, Piza-Katzer H . [Van- der-Woude syndrome]. Klin Padiatr 2008; 220: 26–28.

Du X, Tang W, Tian W, et al. Novel IRF6 mutations in Chinese patients with Van der Woude syndrome. J Dent Res 2006; 85: 937–940.

Gatta V, Scarciolla O, Cupaioli M, Palka C, Chiesa PL, Stuppia L . A novel mutation of the IRF6 gene in an Italian family with Van der Woude syndrome. Mutat Res 2004; 547: 49–53.

Ghassibe M, Revencu N, Bayet B, et al. Six families with van der Woude and/or popliteal pterygium syndrome: all with a mutation in the IRF6 gene. J Med Genet 2004; 41: e15.

Item CB, Turhani D, Thurnher D, et al. Van der Woude syndrome: variable penetrance of a novel mutation (p.Arg 84Gly) of the IRF6 gene in a Turkish family. Int J Mol Med 2005; 15: 247–251.

Kantaputra PN, Limwongse C, Assawamakin A, et al. A novel mutation in IRF6 underlies hearing loss, pulp stones, large craniofacial sinuses, and limb anomalies in Van der Woude Syndrome patients. Oral Biosci Med 2004; 4: 277–282.

Kayano S, Kure S, Suzuki Y, et al. Novel IRF6 mutations in Japanese patients with Van der Woude syndrome: two missense mutations (R45Q and P396S) and a 17-kb deletion. J Hum Genet 2003; 48: 622–628.

Kim Y, Park JY, Lee TJ, Yoo HW . Identification of two novel mutations of IRF6 in Korean families affected with Van der Woude syndrome. Int J Mol Med 2003; 12: 465–468.

Matsuzawa N, Shimozato K, Natsume N, Niikawa N, Yoshiura K . A novel missense mutation in Van der Woude syndrome: usefulness of fingernail DNA for genetic analysis. J Dent Res 2006; 85: 1143–1146.

Matsuzawa N, Yoshiura K, Machida J, et al. Two missense mutations in the IRF6 gene in two Japanese families with Van der Woude syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004; 98: 414–417.

Mostowska A, Wojcicki P, Kobus K, Trzeciak WH . Gene symbol: IRF6. Disease: Van der Woude syndrome. Hum Genet 2005; 116: 534.

Osoegawa K, Vessere GM, Utami KH, et al. Identification of novel candidate genes associated with cleft lip and palate using array comparative genomic hybridisation. J Med Genet 2008; 45: 81–86.

Peyrard-Janvid M, Pegelow M, Koillinen H, et al. Novel and de novo mutations of the IRF6 gene detected in patients with Van der Woude or popliteal pterygium syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 1261–1267.

Shotelersuk V, Srichomthong C, Yoshiura K, Niikawa N . A novel mutation, 1234del(C), of the IRF6 in a Thai family with Van der Woude syndrome. Int J Mol Med 2003; 11: 505–507.

Tan EC, Lim EC, Yap SH, et al. Identification of IRF6 gene variants in three families with Van der Woude syndrome. Int J Mol Med 2008; 21: 747–751.

Wang X, Liu J, Zhang H, et al. Novel mutations in the IRF6 gene for Van der Woude syndrome. Hum Genet 2003; 113: 382–386.

Ye XQ, Jin HX, Shi LS, et al. Identification of novel mutations of IRF6 gene in Chinese families with Van der Woude syndrome. Int J Mol Med 2005; 16: 851–856.

Zechi-Ceide RM, Guion-Almeida ML, de Oliveira Rodini ES, Jesus Oliveira NA, Passos-Bueno MR . Hydrocephalus and moderate mental retardation in a boy with Van der Woude phenotype and IRF6 gene mutation. Clin Dysmorphol 2007; 16: 163–166.

Bertele G, Mercanti M, Gangini GN, Carletti V . A familiar case of popliteal pterygium syndrome. Minerva Stomatol 2008; 57: 309–322.

Schutte BC, Bjork BC, Coppage KB, et al. A Preliminary gene map for the Van der Woude syndrome critical region derived from 900 kb of genomic sequence at 1q32–q41. Genome Res 2000; 10: 81–94.

Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P . Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res 1998; 8: 175–185.

Cann HM, de Toma C, Cazes L, et al. A human genome diversity cell line panel. Science 2002; 296: 261–262.

Burge C, Karlin S . Prediction of complete gene structures in human genomic DNA. J Mol Biol 1997; 268: 78–94.

Blanton SH, Cortez A, Stal S, Mulliken JB, Finnell RH, Hecht JT . Variation in IRF6 contributes to nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate. Am J Med Genet A 2005; 137: 259–262.

Ghassibe M, Bayet B, Revencu N, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-6: a gene predisposing to isolated cleft lip with or without cleft palate in the Belgian population. Eur J Hum Genet 2005; 13: 1239–1242.

Park JW, McIntosh I, Hetmanski JB, et al. Association between IRF6 and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate in four populations. Genet Med 2007; 9: 219–227.

Scapoli L, Palmieri A, Martinelli M, et al. Strong evidence of linkage disequilibrium between polymorphisms at the IRF6 locus and nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate, in an Italian population. Am J Hum Genet 2005; 76: 180–183.

Zucchero TM, Cooper ME, Maher BS, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 6 (IRF6) gene variants and the risk of isolated cleft lip or palate. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 769–780.

Jugessur A, Rahimov F, Lie RT, et al. Genetic variants in IRF6 and the risk of facial clefts: single-marker and haplotype-based analyses in a population-based case-control study of facial clefts in Norway. Genet Epidemiol 2008; 32: 413–424.

Richardson RJ, Dixon J, Malhotra S, et al. Irf6 is a key determinant of the keratinocyte proliferation-differentiation switch. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 1329–1334.

Ingraham CR, Kinoshita A, Kondo S, et al. Abnormal skin, limb and craniofacial morphogenesis in mice deficient for interferon regulatory factor 6 (Irf6). Nat Genet 2006; 38: 1335–1340.

Gunasekaran K, Nagarajaram HA, Ramakrishnan C, Balaram P . Stereochemical punctuation marks in protein structures: glycine and proline containing helix stop signals. J Mol Biol 1998; 275: 917–932.

Qin BY, Liu C, Lam SS, et al. Crystal structure of IRF-3 reveals mechanism of autoinhibition and virus-induced phosphoactivation. Nat Struct Biol 2003; 10: 913–921.

Bailey CM, Khalkhali-Ellis Z, Kondo S, et al. Mammary serine protease inhibitor (Maspin) binds directly to interferon regulatory factor 6: identification of a novel serpin partnership. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 34210–34217.

Cooper DN, Youssoufian H . The CpG dinucleotide and human genetic disease. Hum Genet 1988; 78: 151–155.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01-DE013513 (BCS, MJD), R01-DE08559 (JCM), and P50-DE016215 (BCS, JCM, MLM, MJD) and by the Fonds Spéciaux de Recherche—Université catholique de Louvain, the Fonds national de la recherche scientifique (F.N.R.S.) (to M.V., a “Maître de recherches du F.N.R.S.”). M. Ghassibé was supported by a fellowship from F.R.I.A. (Fonds pour la formation à la recherche dans l'industrie et dans l'agriculture). The authors thank the families that participated in this study, Amy Mach and Jamie L'Heureux for administrative assistance with samples, Kristin Orr, Sally Santiago, Marla Johnson, and Theresa Zucchero for technical assistance, and the following clinicians for participating in this study, Melissa Lees, Koen Devriendt, Geert Mortier, Lionel van Maldergem, Mieke Bouma, David Genevieve, and Aurora Sanchez.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.geneticsinmedicine.org).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Lima, R., Hoper, S., Ghassibe, M. et al. Prevalence and nonrandom distribution of exonic mutations in interferon regulatory factor 6 in 307 families with Van der Woude syndrome and 37 families with popliteal pterygium syndrome. Genet Med 11, 241–247 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e318197a49a

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e318197a49a

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Characterising the loss-of-function impact of 5’ untranslated region variants in 15,708 individuals

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Genetic heterogeneity in Van der Woude syndrome: identification of NOL4 and IRF6 haplotype from the noncoding region as candidates in two families

Journal of Genetics (2018)

-

Tooth agenesis and orofacial clefting: genetic brothers in arms?

Human Genetics (2016)

-

Clinical and molecular findings in a Moroccan patient with popliteal pterygium syndrome: a case report

Journal of Medical Case Reports (2014)

-

A combined targeted mutation analysis of IRF6 gene would be useful in the first screening of oral facial clefts

BMC Medical Genetics (2013)