Abstract

Purpose: Mitochondrial DNA testing is typically performed by targeted mutation analysis only. We applied a more comprehensive approach to study the mitochondrial genome in 24 pediatric patients with idiopathic cardiomyopathy.

Methods: Patients in the cohort did not show overt multisystemic disease and were previously tested for mutations in a subset of structural genes associated with cardiomyopathy. Mutation screening of the mitochondrial DNA by multiplex denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography was complemented by sequence analysis.

Results: We identified 130 individual (unique) sequence changes. Among several potentially pathogenic changes, a novel heteroplasmic mutation in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase subunit 4 (10677G>A) was identified in one fraternal twin with worse clinical symptoms than his sibling. Another proband carried homoplasmic mutation 13708G>A (in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase subunit 5) that has been associated with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy.

Conclusions: Changes in mitochondrial DNA may represent a relatively rare cause of idiopathic pediatric cardiomyopathies and/or influence their phenotypic expression. Interpretation of variants with uncertain pathogenicity, however, currently impedes clinical diagnostic use of comprehensive mitochondrial DNA testing. Whereas combined use of multiplex denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography and sequencing is more comprehensive than targeted mutation analysis, measurement of additional functional parameters, such as tissue respiratory chain activity, remains important to establishing a definitive diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

We performed a pilot study in which mitochondrial (mt) DNA fragments were screened by multiplex denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (mDHPLC), followed by selective DNA sequencing. This approach was evaluated with mtDNA from 24 children affected with cardiomyopathy of unknown origin. Pediatric cardiomyopathies are relatively rare and debilitating disorders of the heart muscle with an incidence of approximately 1/100,000. The two major classes of dilated (51%) and hypertrophic (42%) cardiomyopathy constitute the leading cause of heart failure, required heart transplantation, and sudden cardiac death. Pediatric cardiomyopathies are both clinically and genetically heterogeneous, and currently the etiology remains obscure in approximately two thirds of affected children.1–3 In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the most frequently affected genes include the β-myosin heavy chain gene (MYH7),4–7 cardiac troponin T (TNNT2),5,6,8–10 and, if present in combination with Wolf-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, the adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase gene (PRKAG2).9,11,12

Pediatric cardiomyopathy, in contrast to its overall incidence, is a frequent (up to 40%) phenotype in mitochondrial conditions, and occurs either as one clinical feature of a multisystem disorder or in isolation.13–15 Because mtDNA mutations often result in respiratory chain deficiencies, the greatest impact occurs in tissues with high oxidative metabolism requirements, such as cardiac muscle. In pediatric cardiomyopathy, the respiratory enzymes associated with complexes I, III, IV, and V are most frequently affected. Because some of their peptide subunits are encoded by the mitochondrial genome rather than by nuclear genes, mtDNA mutations are likely causes of these respiratory enzyme deficiencies.16–18

DNA analysis of the mitochondrial genome is challenging for several reasons. First, mutations occur throughout the 16.6-kb mt genome, which encodes 13 respiratory chain peptides, 2 ribosomal ribonucleic acids (rRNA), and 22 transfer ribonucleic acids (tRNA). Because of its size, however, direct sequencing is often prohibitively expensive and time consuming, unless it is performed in a high-throughput facility. As a consequence, routine testing for mtDNA mutations is typically limited to targeted mutation analysis. Second, many known mitochondrial mutations are characterized by heteroplasmy, the presence of a mixed population of wild-type and mutant mtDNA molecules within a cell or tissue. The percentage of heteroplasmy for a specific mtDNA mutation can vary from tissue to tissue within the same individual and must be above a tissue- and mutation-specific threshold before it is likely to produce a pathogenic effect. Third, the mitochondrial genome is highly polymorphic. This variability, together with the phenomenon of heteroplasmy, complicates interpretation of the significance of identified sequence changes.

mDHPLC is a recently developed approach toward screening the entire mitochondrial genome for unknown mutations.19–26 Because mDHPLC recognizes heteroduplex formation, which occurs when a mixture of two alleles is present in an amplicon (present in heterozygosity and in heteroplasmy), it is theoretically highly suitable for the detection of mitochondrial heteroplasmy. Direct sequencing of the mtDNA is still required to identify the exact nature and location of any changes discovered by mDHPLC, but the number of mtDNA amplicons to be sequenced is expected to be markedly reduced. We present a comparison of mDHPLC and DNA sequencing for mitochondrial genome analysis, and report on the mutations identified in our pediatric study group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

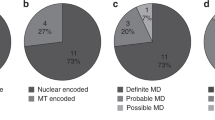

We identified 24 patients within a UCSF cardiomyopathy genetics research cohort of over 200 patients based on the presence of idiopathic cardiomyopathy and medical and family history compatible with a mitochondrial (maternal) pattern of inheritance. Informed written consent was obtained from all study participants under a protocol approved by the Committee on Human Research at University of California, San Francisco. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes according to standard methods. DHPLC and DNA sequencing analysis of the beta myosin heavy chain gene (MYH7) and the cardiac troponin T gene (TNNT2) were completed for all included patients, before this study. All were negative for mutations in these genes. In patients with the WPW phenotype, the PRKAG2 gene was also screened and found to be negative. Participants were also evaluated by medical history, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram, and transthoracic echocardiography. The individual patient phenotypes are summarized in Table 1. Apart from one patient with sensorineural deafness, none of the patients had phenotypes that are known to potentially contribute to the mitochondrial disease spectrum. Tissues from cardiac biopsies or skeletal muscle were not available to us and respiratory enzyme studies could not be performed.

Mitochondrial DNA analysis by mDHPLC

The previously obtained DNA from whole blood leukocytes was used to investigate the mitochondrial genome by mDHPLC and direct DNA sequencing. In addition, nine positive controls from patients with functionally significant mitochondrial myopathies were available for initial testing by mDHPLC and DNA sequencing.

First, the mitochondrial DNA was comprehensively and specifically amplified in 19 overlapping sections. The larger amplicons were then digested with restriction enzymes to create 63 fragments of the correct size for DHPLC analysis according to the MitoScreenTM assay guidelines (Transgenomic, Omaha, NE) (Fig. 1). Each DNA sample was mixed with the ion pairing reagent triethylammonium acetate to facilitate binding of the DNA to a hydrophobic DNASep cartridge (Transgenomic) and then eluted using an acetonitrile gradient. Chromatographic separation of samples was analyzed using the WAVE Nucleic Acid Fragment Analysis System (Transgenomic) and depended on factors such as size and percentage of helicity. Heteroduplex DNA species (indicative of heteroplasmic changes) eluted earlier from the column than homoduplex (indicative of homoplasmy) DNA and were identified by comparing the chromatogram of the sample with that from a control. Each sample analysis was performed at up to five denaturing temperatures for optimal detection of heteroduplex formation. A limitation of this mDHPLC protocol is that homoplasmic changes, which would not result in heteroduplex DNA species, cannot be detected.

Flowchart of the mDHPLC assay steps and sequencing analysis. The mitochondrial genome was amplified in 19 overlapping sections according to the Mitoscreen Assay protocol (Transgenomic). The majority of amplicons were digested with restriction enzymes and analyzed at multiple temperatures. Variant peak profiles were further investigated by DNA sequencing. *One representative fragment was typically sequenced in cases of highly similar variant DHPLC patterns.

Sequence analysis and interpretation

We designed 146 primers to reamplify and sequence smaller fragments of the individual amplicons. One patient amplicon representative of each variant mDHPLC spectral pattern (from each group of common chromatographic patterns) was selected for reamplification. Amplicons were sequenced to explore the validity of the aberrant spectra and to definitively characterize the nature and location of a suspected change. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) purification was performed using the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Purified samples were sequenced directly with fluorescent di-deoxy terminators on an ABI 3100 sequencing instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Contigs were assembled and compared with the consensus reference sequence (Genbank accession number AC_000021.2) using Mutation Surveyor 2.51 software (SoftGenetics, State College, PA) or GCG Sequence Analysis (www.gcg.com). Identified sequence changes were confirmed by DNA sequencing in the reverse direction.

Those detected variants that were located in the coding regions of the mtDNA were further analyzed using the SIFT program (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant, http://blocks.fhcrc.org/sift/SIFT.html), a mutation interpretation tool for predicting the effect on protein function of an amino acid substitution. Several mitochondrial databases were consulted to aid in clinical interpretation of the results, including the MitoDat (http://www-lecb.neifcrf.gov/mitoDat/), Mitomap (http://www.mitomap.org/), and OMIM databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=omim).

RESULTS

Diagnostic methods used for mtDNA analysis

To better understand the molecular diagnostic approaches to mitochondrial disease currently available, we compiled the available testing options from the Genetests website (http://www.genetests.org), summarized in Table 2. Of the total number of assay approaches offered in U.S. clinical laboratories, 78.9% (112/142) are targeted mutation analyses. Mutation scanning methods such as DHPLC are offered only in 2.1% (3/142) of all approaches. These are applied for MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes) and MERRF (myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers), and for other, not further categorized or defined, suspected mitochondrial conditions. Sequence analysis for select exons, or for an entire coding region, comprises 7% (10/142) of the total number of offered assay approaches. Thus, complete analysis of the mitochondrial genome by mutation scanning or by direct sequencing is still rarely offered in a diagnostic setting (Table 2).

mtDNA changes identified by mDHPLC and sequencing

DHPLC and DNA sequencing analysis of the MYH7 and the TNNT2T genes were completed for all included patients, in a separate study. In patients with the WPW phenotype, the PRKAG2 gene was also investigated. None of the patients carried mutations in these genes. mDHPLC chromatograms suggestive of heteroplasmic sequence variants, when compared with reference DNA chromatograms, were observed for every patient in the study. Of the total number of amplified products analyzed by mDHPLC, 27% (114/421) displayed an elution pattern that deviated from that of the unaffected control. Identical variant mDHPLC patterns generated from the same amplified fragments were noted in multiple patients and one representative patient amplicon for each variant mDHPLC spectral pattern was reamplified and sequenced. Of all 37 sequenced fragments, only 10 contained heteroplasmic nucleotide changes, the majority of which were either polymorphisms or synonymous substitutions with no effect on the encoded amino acid. One common polymorphic site was present at nucleotide 309 in the control region of the mitochondrial genome. Heteroplasmic insertions were detected at this position in three different patients, although the number of C nucleotides inserted varied, and this number directly and reproducibly impacted the appearance of the DHPLC chromatogram (Fig. 2). The majority of nucleotide changes identified by DNA sequencing were homoplasmic. They were only detected when those fragments suspected of containing heteroplasmic mutations were sequenced, because the DHPLC method does not detect homoplasmic changes in single patient samples. The summary of identified sequence changes (Table 3) includes only those sequence variants that had been reported to be associated with a clinical phenotype, resulted in an amino acid change to the encoded protein, or had not been previously reported in the Mitomap database and may be novel. A total of 130 individual (unique) sequence changes were identified in our analysis.

Example of variant peak profiles for one mitochondrial amplicon. Heteroduplex DNA species indicative of heteroplasmic mutations elute earlier from the separation column than do homoduplex DNA samples. Distinct variant profiles of mitochondrial fragment 3 (nucleotides 29–480 in the D-loop) were detected in the presence of very similar sequence changes, by comparison with an unaffected control. Variant peaks are indicated by arrows.

Prediction of functionally pathogenic effects

Although there were several examples in our patient group of sequence changes that resulted in amino acid substitutions, relatively few of these changes were expected to have an overall impact on the function of the protein, as predicted by the SIFT mutation interpretation tool (Table 3). One exception was the 13708G>A mutation, a homoplasmic substitution in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) dehydrogenase subunit 5 associated with Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) that was detected in Patient 8 of our subject group. This allele changes the moderately conserved alanine at amino acid 458 to a threonine (Ala458Thr) in ND5. This mutation does not in itself seem to cause LHON, but is present in about 30% of white patients as compared to 6% of random population controls. A second homoplasmic substitution in the same NADH dehydrogenase subunit was observed in this patient at position 13768 (T>C) (http://www.mitomap.org/) (Fig. 3). Both nucleotide changes were additionally identified in the mitochondrial genome of the patient's unaffected mother, thereby confirming maternal inheritance. Interestingly, this patient was diagnosed with WPW syndrome and with cardiomyopathy. Such pre-excitation syndromes have been previously observed in families diagnosed with LHON and homoplasmic rather than heteroplasmic changes are typical of this mitochondrial disorder.19,27–30

Variant mDHPLC peak profile and two underlying sequence changes in the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 gene. a, Left: the expected peak profile of mitochondrial fragment 17 (nucleotides 13172–14610), which is digested by the Alu I and Dde I restriction enzymes before mDHPLC. Right: aberrant chromatogram of Patient 8, because of a mutation-induced change in the restriction pattern. b, Sequence analysis of fragment 17 in Patient 8 demonstrated two homoplasmic sequence changes. The 13708G>A mutation (left) has been reported in LHON syndrome. Variant peaks are indicated by arrows. RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Only one heteroplasmic mutation with a potential effect on protein function was identified in this patient group. This novel substitution (10677G>A) was discovered in the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4L of Patient 13, who was one of a set of dizygotic twins enrolled in the study. A second previously unreported but homoplasmic substitution (5494T>G) with a positive SIFT effect was also found in this patient, in NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 (Fig. 4). This homoplasmic substitution was also detected in Patient 12, who is the sibling of Patient 13, and in the mother. The heteroplasmic substitution was neither present in Patient 12, whose cardiomyopathy symptoms were more benign, nor in the mother of the twins. Thus, it seems to be a spontaneous additional change.

Heteroplasmic and homoplasmic sequence changes in a twin. Homoplasmic substitution 5494T>G (arrow), with a positive SIFT effect predicting functional significance, was identified in NADH dehydrogenase subunit 2 of Patient 13. A novel heteroplasmic change, 10677G>A (arrow), with a potential effect on protein function, was identified in NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4L of the same patient. The heteroplasmic sequence variant was absent in the less severely affected twin.

DISCUSSION

Of the 24 pediatric cardiomyopathy patients in our study, two carried a total of three mitochondrial changes with a predicted protein effect (Table 3). Two of these changes were novel (10677G>A and 5494T>G), and one had been previously associated with LHON (Mitomap: http://www.mitomap.org/). Of note, three additional changes found in our study group were previously reported in individuals with mitochondrial phenotypes (Table 3). Two have no predicted SIFT effect on protein function and one occurred in a noncoding region of the mtDNA. Thus, these predictions and associations must be interpreted with caution unless functional studies and molecular analyses of a large group of control individuals can support or reduce the possibility of pathogenicity. For variants in the mtDNA, however, this may be particularly challenging, given that the level of cellular heteroplasmy, together with the tissue distribution, can markedly influence clinical expression.31,32 This could also, at least in part, explain the clinically unaffected status of the mother of the dizygotic twins (Patients 12 and 13) who were both affected with cardiomyopathy, albeit to different degrees. She shared a previously unreported homoplasmic change (5494T>G) with both children (Fig. 4). The mother of Patient 8 was also clinically unaffected although she shared both of her child's homoplasmic changes, one of which has been connected with LHON (Fig. 3).

The overall low frequency of mtDNA mutations identified in our pediatric patient cohort could be related to the isolated nature of the cardiomyopathy in our studied families. Expanding inclusion criteria to include patients with multisystemic disease suggestive of mitochondrial conditions would likely raise the mutation detection yield. In addition, however, mutations in the mtDNA would not be identified if the defect were present in a nuclear gene that was not investigated in our study. Nuclear genes such as FXN (OMIM number *606829), SLC25A20 (OMIM number +212138), SCO2 (OMIM number *604272), TAZ (OMIM number *300394), and ACADVL (OMIM number *609575), which encode mitochondrial proteins, can cause an array of phenotypic features including cardiovascular diseases such as cardiomyopathy.

In our experience with the MitoScreenTM assay on a WAVE Nucleic Acid Fragment Analysis System (Transgenomic), we found that mDHPLC analysis is a relatively cost-effective scanning method for the screening for heteroplasmic sequence variants in the mitochondrial genome, when compared with direct DNA sequencing. It expands upon targeted mutation analysis to include the potential detection of previously unknown heteroplasmic sequence changes, as demonstrated in this study. The mDHPLC technique also provides the increased detection required for identification of heteroplasmic changes that would be missed by conventional sequencing methods alone, because the threshold for detection of heteroplasmy by DNA sequencing approximates 15–20%. Although mDHPLC is a screening method which may not detect all sequence changes in areas with high helicity, the reported reproducible sensitivity of DHPLC using this system was 0.01%,20 0.5%,19 and 2.5%25 in various studies, depending on the targeted mutation.

mDHPLC by itself is unable to positively characterize the exact location and nature of a suspected heteroplasmic change and abnormal chromatographic patterns should be further investigated with a secondary method of identification. We chose to verify our results with direct DNA sequencing, but only detected heteroplasmic sequence variants in 10 fragments, a small proportion (8.8%, 10/114) of the mitochondrial fragments analyzed that displayed abnormal mDHPLC patterns. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that mDHPLC, with its increased sensitivity, was able to identify several mitochondrial fragments with heteroplasmic variants in which the level of heteroplasmy fell below the threshold of detection for sequencing. Alternative techniques with greater sensitivity, such as TA cloning, may be required for the definitive characterization of all heteroplasmic sequence variants discovered by mDHPLC analysis. Another concern with this approach for mtDNA analysis was that mDHPLC is limited to the detection of heteroplasmic sequence variants only. Homoplasmic changes will not typically be detected with mDHPLC. Several mtDNA mutations associated with mitochondrial disease, however, are pathogenic when homoplasmic rather than heteroplasmic, particularly those linked to SNHL (SensoriNeural Hearing Loss)30 and LHON.31 We were able to discover homoplasmic sequence variants in our patient group only after sequencing those mitochondrial fragments suspected of containing heteroplasmic nucleotide changes. Of course, the mDHPLC protocol could be modified to include detection of homoplasmic sequence variants by mixing patient with control DNA, thereby creating artificial heteroplasmic nucleotide positions that would then be detectable. This approach would not be practical, however, given the heterogeneity of the human mitochondrial genome and the number of naturally occurring polymorphisms that would be identified in addition to potentially pathogenic sequence variants.

In an attempt to streamline our mDHPLC analysis, we typically sequenced one representative patient fragment when identical variant DHPLC chromatographic patterns for the same amplified fragment were observed in multiple patients. The assumption, however, that identical chromatograms indicate the same sequence variant may not be valid in all instances, although highly similar sequence changes can result in reproducibly different patterns (Fig. 2). Indeed, similar peak patterns were obtained for mitochondrial fragment 6 (MT6, nucleotides 2415-3811) for two positive controls, although they carried different mutations (3243A>G and 3260A>G, respectively). Thus, chromatographic patterns are not necessarily specific to individual mutations. The optimal approach, then, would be to confirm all potential sequence variants identified in the mDHPLC screen, for example with either sequencing or cloning. This would be time consuming and costly, unless performed in a high-throughput setting.

Another concern, inherent in the nature of the mDHPLC technique itself, is that the position of a nucleotide change within an amplified fragment determines whether that variant will be detectable by DHPLC, because it must be located within amplified DNA that will be 33–99% helical at a given partially denaturing temperature. The melt profiles of the amplified mtDNA fragments generated by the MitoScreenTM assay indicated that certain nucleotide positions within each fragment were not within the critical range of helicity at any of the recommended denaturing temperatures. Potential sequence changes that fall within these stretches may, therefore, not be detectable with this method. This issue was recently addressed by the development of a set of 67 primer pairs, which define overlapping but not multiplexed optimized PCR fragments. This set covers the entire mitochondrial genome, has GC clamps where necessary for optimal helicity, and could directly be used for subsequent sequence analysis.24

In conclusion, pathogenic mtDNA mutations may be a (relatively rare) cause of idiopathic cardiomyopathy. To identify such changes, mDHPLC analysis seems to be a promising method for relatively fast and economical scanning of the mitochondrial genome for heteroplasmic sequence variants. Diagnostic implementation, however, would require extensive validation. In addition, there are limitations to the scope of information that mDHPLC can provide. For the detection of point mutations and small insertions/deletions, analysis of the entire coding region of the mitochondrial genome by both mDHPLC analysis and direct DNA sequencing would be most likely to identify underlying mitochondrial mutations. Whereas mDHPLC is powerful in the detection of heteroplasmic variants that are frequently pathogenic, DNA sequencing (with a separate set of primers) remains an indispensable complementary tool for identifying homoplasmic changes. More importantly, however, the interpretation of the highly polymorphic mitochondrial genome and the large number of mtDNA variants of uncertain pathogenicity continues to be challenging and is often inconclusive. At present, this problem limits the use of comprehensive mtDNA testing in clinical diagnostics. This may be overcome by the study of larger populations with mitochondrial disease. Additional parameters, such as the demonstration of mitochondrial dysfunction by measurement of functional respiratory chain activity in tissues, need to be integrated in the final diagnostic interpretation to establish disease association of individual sequence changes, whenever possible.

REFERENCES

Sehnert AJ . Use of denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography to detect mutations in pediatric cardiomyopathies. Methods Mol Med 2006; 126: 257–270.

Lipshultz SE, Sleeper LA, Towbin JA, et al. The incidence of pediatric cardiomyopathy in two regions of the United States. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1647–1655.

Nugent AW, Daubeney PE, Chondros P, et al. The epidemiology of childhood cardiomyopathy in Australia. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1639–1646.

Blair E, Redwood C, de Jesus Oliveira M, et al. Mutations of the light meromyosin domain of the beta-myosin heavy chain rod in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 2002; 90: 263–269.

Ackerman MJ, VanDriest SL, Ommen SR, et al. Prevalence and age-dependence of malignant mutations in the beta-myosin heavy chain and troponin T genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive outpatient perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39: 2042–2048.

Van Driest SL, Ackerman MJ, Ommen SR, et al. Prevalence and severity of “benign” mutations in the beta-myosin heavy chain, cardiac troponin T, and alpha-tropomyosin genes in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2002; 106: 3085–3090.

Van Driest SL, Jaeger MA, Ommen SR, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the beta-myosin heavy chain gene in 389 unrelated patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44: 602–610.

Van Driest SL, Ellsworth EG, Ommen SR, et al. Prevalence and spectrum of thin filament mutations in an outpatient referral population with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2003; 108: 445–451.

Mogensen J, Bahl A, Kubo T, Elanko N, Taylor R, McKenna WJ . Comparison of fluorescent SSCP and denaturing HPLC analysis with direct sequencing for mutation screening in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Med Genet 2003; 40: e59.

Morita H, Larson MG, Barr SC, et al. Single-gene mutations and increased left ventricular wall thickness in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2006; 113: 2697–2705.

Oliveira SM, Ehtisham J, Redwood CS, Ostman-Smith I, Blair EM, Watkins H . Mutation analysis of AMP-activated protein kinase subunits in inherited cardiomyopathies: implications for kinase function and disease pathogenesis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2003; 35: 1251–1255.

Vaughan CJ, Hom Y, Okin DA, McDermott DA, Lerman BB, Basson CT . Molecular genetic analysis of PRKAG2 in sporadic Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2003; 14: 263–268.

Lev D, Nissenkorn A, Leshinsky-Silver E, et al. Clinical presentations of mitochondrial cardiomyopathies. Pediatr Cardiol 2004; 25: 443–450.

Holmgren D, Wåhlander H, Eriksson BO, Oldfors A, Holme E, Tulinius M . Cardiomyopathy in children with mitochondrial disease; clinical course and cardiological findings. Eur Heart J 2003; 24: 280–288.

Scaglia F, Towbin JA, Craigen WJ, et al. Clinical spectrum, morbidity, and mortality in 113 pediatric patients with mitochondrial disease. Pediatrics 2004; 114: 925–931.

Marin-Garcia J, Ananthakrishnan R, Goldenthal MJ, Filiano JJ, Perez-Atayde A . Mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle of children with cardiomyopathy. Pediatrics 1999; 103: 456–459.

Marin-Garcia J, Ananthakrishnan R, Goldenthal MJ, Pierpont ME . Biochemical and molecular basis for mitochondrial cardiomyopathy in neonates and children. J Inherit Metab Dis 2000; 23: 625–633.

Guenthard J, Wyler F, Fowler B, Baumgartner R . Cardiomyopathy in respiratory chain disorders. Arch Dis Child 1995; 72: 223–226.

van Den Bosch BJ, de Coo RF, Scholte HR, et al. Mutation analysis of the entire mitochondrial genome using denaturing high performance liquid chromatography. Nucleic Acids Res 2000; 28: E89.

Conley YP, Brockway H, Beatty M, Kerr ME . Qualitative and quantitative detection of mitochondrial heteroplasmy in cerebrospinal fluid using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc 2003; 12: 99–103.

Bayat A, Walter J, Lamb H, Marino M, Ferguson MW, Ollier WE . Mitochondrial mutation detection using enhanced multiplex denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Int J Immunogenet 2005; 32: 199–205.

Liu MR, Pan KF, Li ZF, et al. Rapid screening mitochondrial DNA mutation by using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. World J Gastroenterol 2002; 8: 426–430.

Biggin A, Henke R, Bennetts B, et al. Mutation screening of the mitochondrial genome using denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Mol Genet Metab 2005; 84: 61–74.

Wulfert M, Tapprich C, Gattermann N . Optimized PCR fragments for heteroduplex analysis of the whole human mitochondrial genome with denaturing HPLC. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2006; 831: 236–247.

Lim KS, Naviaux RK, Haas RH . Quantitative mitochondrial DNA mutation analysis by denaturing HPLC. Clin Chem 2007; 53: 1046–1052.

Lim KS, Naviaux RK, Wong S, Haas RH . Pitfalls in the denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mitochondrial DNA mutation. J Mol Diagn 2008; 10: 102–108.

Nikoskelainen EK, Savontaus ML, Huoponen K, Antila K, Hartiala J . Pre-excitation syndrome in Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Lancet 1994; 344: 857–858.

Mashima Y, Kigasawa K, Hasegawa H, Tani M, Oguchi Y . High incidence of pre-excitation syndrome in Japanese families with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy. Clin Genet 1996; 50: 535–537.

Dandekar SS, Graham EM, Plant GT . Ladies with Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy: an atypical disease. Eur J Ophthalmol 2002; 12: 537–541.

Fischel-Ghodsian N . Mitochondrial deafness. Ear Hear 2003; 24: 303–313.

Moraes CT, Atencio DP, Oca-Cossio J, Diaz F . Techniques and pitfalls in the detection of pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations. J Mol Diagn 2003; 5: 197–208.

Leonard JV, Schapira AH . Mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders. I. Mitochondrial DNA defects. Lancet 2000; 355: 299–304.

Acknowledgements

This research was, in part, supported by NIH KO8 HL04068 and Greenberg Young Investigator Award in Cardiovascular Genetics. We thank Dr. Bert Smeets and Alexandra Hendrickx, Department of Clinical Genetics, University of Maastricht, the Netherlands, for the generous contribution of positive control samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schrijver, I., Pique, L., Traynis, I. et al. Mitochondrial DNA analysis by multiplex denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography and selective sequencing in pediatric patients with cardiomyopathy. Genet Med 11, 118–126 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e318190356b

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e318190356b