Abstract

Purpose: Prenatal screening should enable pregnant women to make informed choices. An informed decision is defined as being based on sufficient, relevant information and consistent with the decision maker's values. This study aims to assess to what extent pregnant women make informed choices about prenatal screening, and to assess the psychological effects of informed decision-making.

Methods: The study sample consisted of 1159 pregnant women who were offered the nuchal translucency measurement or the maternal serum screening test. Level of knowledge, value consistency, informed choice, decisional conflict, satisfaction with decision, and anxiety were measured using questionnaires.

Results: Of the participants, 83% were classified as having sufficient knowledge about prenatal screening, 82% made a value-consistent decision to accept or decline prenatal screening, and 68% made an informed decision. Informed choice was associated with more satisfaction with the decision, less decisional conflict (this applied only to test acceptors), but was not associated with less anxiety.

Conclusion: Although the rate of informed choice is relatively high, substantial percentages of women making uninformed choices due to insufficient knowledge, value inconsistency, or both, were found. Informed choice appeared to be psychologically beneficial. The present study underlines the importance of achieving informed choice in the context of prenatal screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Screening programs should aim at enabling people to make informed choices, rather than achieving as high as possible uptake rates.1–5 The paradigm of informed choice is based on both ethical and psychological considerations. By means of informed choice, the ethical principle of autonomy is respected,5–7 and better psychological outcomes are assumed to be achieved.8 Accepting or declining prenatal screening in particular should be founded on informed choice, because of the risks and moral values that play a part: prenatal screening may lead to diagnostic testing, which involves the risk of an iatrogenic abortion and, in case of a positive test result, to the option of termination of pregnancy.9

Although both practitioners and pregnant women consider informed choice as the main objective of offering prenatal screening,3,10 the decision to accept or decline prenatal screening is often not an informed choice.11 Green et al.11 found that, although women want to make informed choices about screening (and when questioned directly, state that their choices were informed), women do not possess the required understanding of prenatal tests to be able to make an informed choice.

Several different definitions of informed choice or informed decision-making exist. They all include at least the following two dimensions: first, the decision should be based on relevant information, and second, it should be consistent with the decision maker's values.1,12–14

Whether or not a decision is based on relevant information can be assessed by measuring the decision maker's knowledge of the different aspects of a certain screening. Although there is no gold standard regarding what constitutes sufficient, relevant knowledge, there is consensus that, with regard to screening, several points are essential to know: characteristics of the condition for which screening is being offered, characteristics of the screening test, and implications of the possible test results.8 Research has shown that women lack sufficient knowledge about the different aspects of prenatal screening, which impedes informed decision-making.11,15,16

The second requisite for an informed choice is value consistency. Values are abstract ideals representing a person's beliefs about ideal modes of conduct.17 As attitudes are tendencies to respond to a concrete object with some degree of favor or disfavor,18,19 they can be considered as a reflection of one's values.1 Therefore, with respect to prenatal screening, in order to assess the decision maker's values, attitudes toward prenatal testing for congenital defects could be measured. Subsequently, value consistency can be assessed by comparing one's attitudes with the actual behavior. Having the screening test done while having a positive attitude toward screening during pregnancy, and declining the prenatal screening test while having a negative attitude toward screening, are both value-consistent decisions.

Although an informed choice should be based on sufficient knowledge as well as value consistency, most studies on informed decision-making did not assess both aspects, but rather focused on measures like the health behavior, knowledge, values or attitudes, or psychological effects, separately.12 Recently, a measure of informed choice (MMIC) was developed and validated by Marteau and colleagues.1,9 This measure is based on a conceptualization of informed choice that respects its multidimensional character and integrates the basic elements of informed choice (i.e., knowledge, attitude, and actual behavior).

Furthermore, little is known about the actual psychological effects of informed choice. Studies assessing the relation between informed choice and outcome measures like decisional conflict, decision satisfaction, and anxiety, are scarce,11 and reported mixed results. Bekker et al.20 found that women who made more informed choices expressed less decisional conflict over time about their decision-making, but there was no effect on anxiety. This association between informed choice and decisional conflict was also found by Michie et al.9 Green et al.,11 however, suggested that informed decision-making is associated with more anxiety and less satisfaction with the decision, as compared with uninformed decision-making. Therefore, it is unclear what the effects of informed choice are.

The aim of this study was to assess to what extent pregnant women who are offered prenatal screening for congenital defects make informed choices. This was done by measuring its basic dimensions (knowledge and value consistency) and combining these two into a measure of informed choice. In addition, this study aimed to assess the psychological effects of informed decision-making.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Setting

Until now in the Netherlands (contrary to many other modern Western countries), prenatal screening for Down syndrome (DS) and Neural Tube Defects (NTDs) is not offered routinely to pregnant women. Only prenatal diagnostic tests are offered routinely to pregnant women over 35 years of age (among women in this age category, the diagnostic test uptake rate is 34%21), and to women with an otherwise increased risk. For this reason, it was necessary to ask permission from the Ministry of Health to carry out this study. Therefore, it is important to stress that the prenatal screening tests that were offered to pregnant women were exclusively offered to the participants in our study.

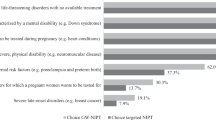

The study presented in this article is part of a larger research project, designed to give more insight into the risk perception, informed decision-making, and psychological well-being of pregnant women who are offered prenatal screening for congenital defects. The research project is a randomized controlled trial in which participants were randomized into one of two intervention groups or into the control group. The intervention consisted of offering prenatal screening for congenital defects. Women in the first intervention group were offered the Nuchal Translucency Measurement (NTM), and women in the second intervention group the Maternal Serum screening Test (MST). The NTM screens for DS in the first trimester of pregnancy and is done by ultrasound scanning.22 The MST is a blood test in the second trimester of pregnancy (“triple-test”) and screens for DS and NTDs.23

Both prenatal screening tests provide an individualized risk estimation of having a child with one of these disorders, and thus identify a high-risk subgroup within a population of pregnant women. Subsequently, this subgroup of women with an increased risk is offered prenatal diagnostic testing in order to provide a certain diagnosis.

Information booklet

The test offer consisted of a sent-home booklet containing information about the particular test, and a standardized oral explanation by the woman's midwife or gynecologist during a consultation. The following topics were covered in the information booklets: characteristics of DS and NTDs (information about NTDs is covered only in the MST booklet), age-specific risks of DS, population risk of NTDs, procedure of the screening test, the meaning of a negative or a positive test result, options available after a positive test result, and procedure of the diagnostic tests (amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling). The booklet paid special attention to the decision-making process, and several advantages and disadvantages of prenatal screening were listed. The leaflets were pilot-tested for comprehensibility.

Procedure

Women attending 1 of 44 participating midwifery and gynecology practices from May 2001 to May 2003 before 16 weeks of gestation were asked permission to be sent a research information letter and an informed consent form. Practices were allocated in several areas throughout the Netherlands to ensure a representative sample. Women who gave informed consent to participate in the study were asked to fill out postal questionnaires before and after the prenatal screening offer. The first questionnaire was sent before the pregnant women received the screening information booklet, and this contained questions about background variables such as age, education, parity, and religion. The second questionnaire was sent and filled out after they had read the booklet and decided for or against prenatal screening, but before they had received the test result. It included measures of knowledge, attitude, decisional conflict, and anxiety. The third questionnaire was sent after receiving the test result. Among other measures, this questionnaire contained a measure of satisfaction with the decision. The third questionnaire also asked about test uptake. Women in the control group and women who declined screening received the questionnaires at comparable points in time.

Sample

During the recruitment period, 4076 women were asked to participate in the study; 2986 (73%) women gave informed consent and returned the first questionnaire. Of these women, 76% (n = 2277) also filled out and returned the second questionnaire, and 66% (n = 1968) also returned the third questionnaire. Analysis of nonresponse revealed that the main reasons for not participating in the study were lack of time or lack of interest. For the present study, only data of the intervention groups were used (n = 1421). Of the women who accepted the prenatal screening test, only 20 turned out to have an increased risk. These cases were excluded. Due to missing values in the different questionnaires, another 242 cases had to be excluded, which resulted in a study sample with data of 1159 women.

Measures

The following sociodemographic variables were assessed: age, parity, educational level, and level of religiosity. Whether or not a pregnant women had had a prenatal screening test was asked in the third questionnaire.

Knowledge about prenatal screening for congenital defects was measured by a scale that consisted of seven items for women in the NTM group and 10 items for women in the MST group (see Appendix). The MST scale corresponded with the NTM scale and had some additional questions about NTD. The items were based on the information that was covered in the prenatal screening information booklets. The scales were composed of yes/no items about three topics: characteristics of DS and NTDs (only for the MST group), characteristics of the screening test, and implications of the possible test results. Because no gold standard exists as to what constitutes sufficient knowledge, it was determined that the guess-corrected midpoint would serve as cutoff. Correction for guessing was performed using Abbott's blind guessing formula.24 This indicated sufficient knowledge when more than five (NTM scale) or seven (MST scale) questions were answered correctly, and insufficient knowledge when fewer questions were answered correctly.

Attitude toward having a prenatal screening test for congenital defects was measured by an attitude scale that consisted of four items (see Appendix). The scale ranged from 4 to 20. The scale was internally consistent: Cronbach's alpha was 0.79. The attitude scores were normally distributed with the median score at the midpoint of the scale. The midpoint of the scale equals a neutral attitude. It is theoretically incorrect to classify women with a neutral attitude as positive or negative toward prenatal screening. Consequently, attitude scores were not dichotomized, but they were reclassified into three equal categories: negative attitude, neutral attitude, and positive attitude.

To assess value consistency, attitude scores were combined with test uptake. When positive attitudes involved accepting the prenatal test or negative attitudes involved declining the test, a value-consistent decision was made. Conversely, a value-inconsistent decision was made when positive attitudes were accompanied with declining the test, or negative attitudes were accompanied with accepting the test.

To determine whether a decision was an informed choice or not, dichotomized knowledge scores and value consistency scores were integrated. This resulted in informed decisions that were value-consistent and based on good knowledge, and in uninformed decisions that were value-inconsistent and/or based on poor knowledge.

Decisional conflict was measured by O'Connor's Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS), in which decisional conflict is defined as a state of uncertainty about the courses of action to take.13 Total scores were divided by the number of items, so the scale ranged from 1 to 5. In our sample, Cronbach's alpha for the total scale was 0.84. Satisfaction with the decision was assessed by a scale that consisted of four five-point Likert items about decision satisfaction after the decision was made, with items like “I think I made a good decision,” and “I am happy with the decision I made.” The total scores were divided by the number of items, thus the scale ranged from 0 to 5. The scale was internally consistent with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.69. Anxiety was measured using the Dutch version of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory version Y.25 In our sample, Cronbach's alpha was 0.93.

Analysis

Group differences were tested using χ2 tests for categorical variables, and t tests for continuous variables.

Approvals

According to the Dutch Population Screening Act, permission for this study had first to be granted by the Minister of Health. After a recommendation from the Health Council, the permit was granted.26 The present study was also approved by the Ethical Committee of the VU University Medical Center.

RESULTS

The sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Forty-four percent of the pregnant women decided to accept the offer of the prenatal screening test. Test uptake was significantly higher among participants being offered the NTM (52%) compared to those being offered the MST (35%) (χ2 = 33.3, P < 0.001).

Of the participants, 83% (n = 957) were classified as having sufficient knowledge about prenatal screening to be able to make an informed choice; 17% (n = 202) had insufficient knowledge. There were no significant differences between the test acceptors and the test decliners, nor between the NTM and the MST group. Higher proportions of sufficient knowledge were observed among women with higher levels of education (χ2trend = 55.1, P < 0.001), and among women in higher age groups (χ2trend = 7.63, P < 0.01) (Table 2).

The mean attitude score was 12.2 (SD = 3.7), the median was 12. Participants who accepted the prenatal screening test had significantly more positive attitudes compared to women who declined the screening test (F = 481.4, P < 0.001). As women with neutral attitudes can not be classified as value-consistent or not, these cases are left out of consideration for calculation of value consistency rates (n = 1159 − 327 = 832). Numbers of value-consistent and value-inconsistent decisions are shown in Table 3. Of the participants with a positive attitude, 313 women accepted prenatal screening, and 369 participants with a negative attitude declined prenatal screening. This resulted in 682 (82%) participants making value-consistent decisions. Of the acceptors, 52 participants had a negative attitude, and 98 decliners had a positive attitude toward prenatal screening. This totalized to 150 participants (18%) who did not make value-consistent decisions. From Table 2, it can be seen that women over 35 years of age made significantly less value-consistent decisions as compared to younger women (χ2 = 28.4, P < 0.001).

Of the pregnant women who participated in this study, 68% had made an informed choice, i.e., they made a choice that was based on sufficient knowledge and consistent with the decision maker's values (Table 4). Consequently, 32% (n = 265) of the women made an uninformed choice, 47% (n = 123) of which was due to value inconsistency, 43% (n = 115) was due to poor knowledge, and 10% (n = 27) was due to both value inconsistency and poor knowledge. Participants over 35 years of age made significantly less informed decisions (51%, χ2 = 11.6, P < 0.01). Furthermore, informed choice appeared to be associated with education; the higher the educational level, the higher the rate of informed choice (χ2trend = 16.0, P < 0.001) (see Table 2).

Decisional conflict, satisfaction with the decision, and anxiety

As can be seen from Table 5, informed choice was associated with less decisional conflict; however, this applied only to test acceptors. Both informed acceptors and decliners had significantly higher scores on the satisfaction with the decision scale as compared to uninformed deciders (t = 4.9, P < 0.001 and t = 2.1, P < 0.05, respectively). Although informed choice was associated with less anxiety for the test acceptors, this difference was not statistically significant (t = 1.8, P = 0.07). For the test decliners, no difference in anxiety scores between the women who made an informed choice and those who made an uninformed choice was observed.

DISCUSSION

The vast majority of the pregnant women had sufficient knowledge about the different aspects of prenatal screening for congenital defects, and most women made value-consistent decisions. Assessment of informed choice revealed relatively high levels of informed decision-making. Informed choice to accept prenatal screening was associated with less decisional conflict and with more decision satisfaction as compared to uninformed choice. Informed choice to decline prenatal screening was related only with higher levels of satisfaction. Anxiety scores were lower (although not statistically significant) only for informed acceptors.

The conclusion that many women were sufficiently knowledgeable about prenatal screening is not supported by other studies, neither is the finding that most pregnant women made informed decisions.11 Both findings may be related to the specific situation in which the screening was offered. Currently, in the Netherlands, prenatal screening is not offered routinely. Therefore, for most of the participants in our study, receiving the offer of a prenatal screening test was something new. Because of the unfamiliarity with prenatal screening as a standard practice, pregnant women in our study presumably made the decision more consciously. This is supported by research from countries where prenatal screening is part of routine prenatal care, which establishes that prenatal screening is no longer something about which a deliberate decision is made.27,28 This so-called normalization or “routinization” of prenatal screening leads to less-informed choices about having prenatal screening. In the Netherlands, the case is quite the opposite because up till now it has not been allowed to offer prenatal screening routinely. Furthermore, the study participants received extensive, well-balanced information (by means of both a booklet and counseling by the midwife or gynecologist) that paid special attention to the decision-making. This also could be an explanation for the high number of informed choice in our study.

The finding that the rate of informed choices was associated with level of education is due to the association of the level of knowledge with educational level. This last association is not surprising and in accordance with previous literature.29–31 More uninformed choices were observed among participants over 35 years of age compared to younger women. This finding seems to be illogical because older women have higher levels of knowledge. However, there is a high rate of value inconsistency in this age group, which is caused by test decliners with a positive attitude concerning prenatal screening, rather than by test acceptors with a negative attitude. These test decliners with a positive attitude presumably declined screening because they preferred prenatal diagnostic testing. At the time of the study, in the Netherlands, these women over 35 years of age were routinely offered prenatal diagnostic testing. So, in the model, these older participants were frequently classified as value-inconsistent and, consequently, as uninformed decision makers. This is a shortcoming of the model, because these women did in fact make value-consistent, informed choices to decline prenatal screening.

Although the majority of the decisions were informed choices, substantial percentages of uninformed choices were found. Almost one third of all decisions were categorized as uninformed choices. Forty-seven percent of these decisions were ascribed to value inconsistency, 43% to insufficient knowledge, and 10% to both. Value inconsistency due to declining prenatal screening while having a positive attitude may be the result of practical barriers like requiring a separate return visit.32,33 Another explanation might be that these participants were of the opinion that the screening test was not good enough, as research has shown that many women give this reason (“unfavorable test characteristics”) for declining prenatal screening.34 On the other hand, value inconsistency due to accepting prenatal screening while being negative about it might be attributed to social pressure or normalization of prenatal screening. Further research is needed to investigate the real causes behind value inconsistency.

From the effects on the outcome measures, it can be concluded that informed choice is indeed associated with better psychological outcomes. This underlines the importance of informed choice. However, these positive effects mainly applied to informed choice to accept prenatal screening. That informed choice is associated with less decisional conflict was also found by Michie et al.9 and Bekker et al.,20 and is contradictory to the suggestion of Green et al.11 that informed choice is associated with less decision satisfaction and increased anxiety.

A limitation of this study is that the number of women whose prenatal test resulted in an increased risk of having a child with DS or NTDs was too small to incorporate them in the analysis, and therefore these cases had to be excluded. This low screen positive rate was caused by the small number of high-risk results in the NTM group, probably due to the poor quality of the NTMs performed within our study. Of all pregnant women, those with high-risk results will presumably suffer most from uninformed choice and benefit most from informed choice.9 Studies aiming especially at the high-risk group should be performed to assess the rates of informed choice and its benefits for these women.

Another limitation of the present study is that no measure of the decision-making process is involved in the assessment of informed choice. Some definitions of informed choice include a measure of the decision-making process in addition to knowledge and value consistency.35 By not incorporating the decision-making process, it is still unknown how the information was perceived and whether or not the knowledge was used. Involving the process of decision-making in a measure of informed choice would, for instance, make clearer how risk perception influences decision-making. Integrating a measure of the decision-making process into the assessment of informed choice would probably reveal that some decisions that were formerly classified as informed choices are not the result of a process of deliberation. More research involving the process of decision-making in the assessment of informed choice is needed.

This study underlines the importance of achieving informed choice in the context of prenatal screening. Pregnant women will experience less decisional conflict, and will be more satisfied, when having made an informed choice. Therefore, every effort that can be made to increase the number of informed choices should be carried out. For instance, research has shown that decision aids are able to improve the quality and the level of informedness of prenatal testing decisions,20 and such decision aids should be developed and implemented in the prenatal screening setting. Introducing prenatal screening for congenital defects as part of standard prenatal care should go hand in hand with an adequate system of informing and counseling women about prenatal screening to ensure informed decision-making.

References

Marteau TM, Dormandy E, Michie S . A measure of informed choice. Health Expect 2001; 4: 99–108.

Health Council of the Netherlands. Prenatal screening: Down's syndrome, neural tube defects, routine-ultrasonography. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands, 2001. no. 2001/11.

Williams C, Alderson P, Farsides B . Too many choices? Hospital and community staff reflect on the future of prenatal screening. Soc Sci Med 2002; 55: 743–753.

Raffle AE . Information about screening: Is it to achieve high uptake or to ensure informed choice? Health Expect 2001; 4: 92–98.

Austoker J . Gaining informed consent for screening. BMJ 1999; 319: 722–723.

Llewellyn-Thomas HA . Patients' health-care decision making: a framework for descriptive and experimental investigations. Med Decis Making 1995; 15: 101–106.

Beauchamp T, Childress J . Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Marteau TM, Dormandy E . Facilitating informed choice in prenatal testing: How well are we doing? Am J Med Genet 2001; 106: 185–190.

Michie S, Dormandy E, Marteau TA . The multi-dimensional measure of informed choice: A validation study. Patient Educ Couns 2002; 48: 87–91.

Carroll JC, Brown JB, Reid AJ, Pugh P . Women's experience of maternal serum screening. Can Fam Physician 2000; 46: 614–620.

Green JM, Hewison J, Bekker HL, Bryant LD, Cuckle HS . Psychosocial aspects of genetic screening of pregnant women and newborns: A systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2004; 8: 1–124.

Bekker H, Thornton JG, Airey CM, Connelly JB, Hewison J, Robinson MB et al. Informed decision making: An annotated bibliography and systematic review. Health Technol Assess 1999; 3: 1–156.

O'Connor AM . Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making 1995; 15: 25–30.

Briss P, Rimer B, Reilley B, Coates RC, Lee NC, Mullen P et al. Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med 2004; 26: 67–80.

Bernhardt BA, Geller G, Doksum T, Larson SM, Roter D, Holtzman NA . Prenatal genetic testing: Content of discussions between obstetric providers and pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 91: 648–655.

Smith DK, Shaw RW, Marteau TM . Informed consent to undergo serum screening for Downs syndrome: The gap between policy and practice. BMJ 1994; 309: 776.

Rokeach M . Beliefs, attitudes and values: A theory of organization and change. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1968.

Ajzen I . Attitudes at their very best. Contemp Psychol 1994; 39: 800–801.

Eagly AH, Chaiken S . The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth, Texas: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1993.

Bekker HL, Hewison J, Thornton JG . Applying decision analysis to facilitate informed decision making about prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome: A randomised controlled trial. Prenat Diagn 2004; 24: 265–275.

Nagel HT, Knegt AC, Kloosterman MD, Wildschut HI, Leschot NJ, Vandenbussche FP . Invasive prenatal diagnosis in the Netherlands, 1991–2000: Number of procedures, indications and abnormal results detected. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2004; 148: 1538–1543.

Nicolaides KH, Heath V, Cicero S . Increased fetal nuchal translucency at 11–14 weeks. Prenat Diagn 2002; 22: 308–315.

Benn PA . Advances in prenatal screening for Down syndrome, I: General principles and second trimester testing. Clin Chim Acta 2002; 323: 1–16.

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH . Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994.

van der Ploeg HM . Handleiding bij de Zelf-Beoordelings Vragenlijst (ZBV). Een Nederlandse bewerking van de Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI-DY. Lisse: Swets & Zeitlinger, 2000.

Health Council of the Netherlands: Committee on the Population Screening Act. Population Screening Act: Prenatal screening and risk perception. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands, 1999. no. 1999/04WBO.

Green JM, Statham H . Psychosocial aspects of prenatal screening and diagnosis. In: Marteau TM, Richards M, editors. The troubled helix: social and psychological implications of the new genetics. Cambridge University Press, 1996: 140–163.

Press N, Browner CH . Why women say yes to prenatal diagnosis. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45: 979–989.

Goel V, Glazier R, Holzapfel S, Pugh P, Summers A . Evaluating patient's knowledge of maternal serum screening. Prenat Diagn 1996; 16: 425–430.

Paravic J, Brajenovic-Milic B, Kapovic M, Botica A, Jurcan V, Milotti S . Maternal serum screening for Down's syndrome: A survey of pregnant women views. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1999; 85: 160.

Santalahti P, Aro AR, Hemminki E, Helenius H, Ryynanen M . On what grounds do women participate in prenatal screening? Prenat Diagn 1998; 18: 153–165.

Dormandy E, Hooper R, Michie S, Marteau TM . Informed choice to undergo prenatal screening: a comparison of two hospitals conducting testing either as part of a routine visit or requiring a separate visit. J Med Screen 2002; 9: 109–114.

Dormandy E, Michie S, Weinman J, Marteau TM . Variation in uptake of serum screening: The role of service delivery. Prenat Diagn 2002; 22: 67–69.

Van den Berg M, Timmermans DRM, Kleinveld JH, Garcia E, van Vugt JMG, van der Wal G . Accepting or declining the offer of prenatal screening for congenital defects: test uptake and women's reasons. Prenat Diagn 2005; 25: 84–90.

Bekker HL, Hewison J, Thornton JG . Understanding why decision aids work: Linking process with outcome. Patient Educ Couns 2003; 50: 323–329.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the Prevention Program of the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, grant no. 2200.0085).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

APPENDIX

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van den Berg, M., Timmermans, D., ten Kate, L. et al. Are pregnant women making informed choices about prenatal screening?. Genet Med 7, 332–338 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.GIM.0000162876.65555.AB

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.GIM.0000162876.65555.AB

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Informed choice and routinization of the second-trimester anomaly scan: a national cohort study in the Netherlands

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2023)

-

Knowledge, Attitudes, Willingness to Pay, and Patient Preferences About Genetic Testing and Subsequent Risk Management for Cancer Prevention

Journal of Cancer Education (2022)

-

Couples’ experiences with expanded carrier screening: evaluation of a university hospital screening offer

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

-

Decision-making styles in the context of colorectal cancer screening

BMC Psychology (2020)

-

Attitude, knowledge and informed choice towards prenatal screening for Down Syndrome: a cross-sectional study

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2018)