Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study is to evaluate and grade the extent and severity of ocular involvement in Tessier number 10 cleft.

Patients and methods

A retrospective, noncomparative, interventional case series was conducted between January 2006 and December 2015. Clinical data were reviewed from 59 patients (85 eyes) with Tessier number 10 clefts. Detailed medical history and ophthalmic examination of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of Tessier number 10 cleft were recorded on an itemized data collection form. Ocular manifestations were categorized as upper eyelid defect, symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium (skin growing onto the globe), corneal complications, and lower eyelid ectropion; components were evaluated and graded on a scale from 0 to 3, according to their severity.

Results

More than half of the cases (43 eyes, 53.8%) had severe upper eyelid defect, and severe symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium were observed in 38 eyes (47.5%). Nearly half of the cases (40 eyes, 50.0%) have severe corneal complications, and lower eyelid ectropion was found in 34 eyes (42.5%). The severity of symblepharon, corneal complications, and lower eyelid ectropion were significantly correlated with the upper eyelid defect; the correlation coefficient (r) ranged from 0.844 to 0.629 (P<0.0001).

Conclusion

This study presents the ocular manifestation of Tessier number 10 clefts with large-series cases, and establishes an effective grading system to evaluate Tessier number 10 clefts, which is useful for the diagnosis, treatment, and prediction of outcomes in patients with a Tessier number 10 cleft.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Because of the rarity of craniofacial clefts, their classification is difficult. In 1976, Tessier1 first proposed a classification of craniofacial clefts using the orbit as a central hallmark that is now widely accepted. The clefts are numbered from 0 to 14 and extend along constant axes through the eyebrows or eyelids, the maxilla, the nostrils, and the lip.1 The number 10 cleft is one of the rare defects in the Tessier classification, consisting of congenital coloboma of middle third of the upper eyelid, eyebrow deformities, and a wedge-shaped anterior hairline extension. It may also be accompanied by other ocular anomalies, including symblepharon, cutaneous pterygium (skin growing onto the globe), and corneal complications.2, 3, 4

Upper eyelid colobomas are partial or total lid defects that may be unilateral or bilateral. Symblepharon and cutaneous pterygium always occur at the upper and medial part of the ocular surface; corneal opacification, neovascularization, keratinization, and limbal stem cell deficiency vary in patients, which may lead to significant vision loss. Until now, there are only sporadic case reports on clinical presentation3, 4 and several studies on the surgical management of congenital eyelid coloboma, including Tessier number 10 clefts.2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 However, despite its potentially devastating nature and the increasing indications for ocular reconstructive surgery, there is currently no standardized method for evaluating the spectrum of ocular manifestations and the severity of ocular involvement in this congenital disease.

Therefore, we retrospectively reviewed clinical records and photographs of 59 patients diagnosed with Tessier number 10 clefts visiting our department during the past 10 years, analyzed the ocular manifestations of these cases, and then we proposed an objective method for grading the extent and severity of ocular involvement. Besides upper eyelid defect, symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium, and corneal complications, we also found some patients presented with lower eyelid ectropion. The other aims of this study were to look at correlations between upper eyelid defect, symblepharon, corneal complications, and lower eyelid ectropion in these patients. To our knowledge, this study represents the largest series of patients with Tessier number 10 cleft with ophthalmic complications studied to date. Because it provides a common platform for the discussion and management of these patients, this study has important clinical implications for the diagnosis, treatment, and prediction of outcomes in patients with Tessier number 10 clefts.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted in compliance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. Fifty-nine patients (85 eyes) diagnosed with Tessier number 10 clefts were recruited. Besides the deformities of eyebrow and anterior hairline extension, the main ocular manifestations were upper eyelid defect, symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium, corneal complications (opacification, neovascularization, keratinization, and limbal stem cell deficiency), and lower eyelid ectropion. These cases were referred to the Department of Ophthalmology of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital between January 2006 and December 2015. Family history was unremarkable in all patients. There were no reported histories of craniofacial abnormalities in the extended family, and consanguinity was not present. There was no history of maternal exposure to radiation, illicit drug use, chemical exposure, or infections during pregnancy. A full ophthalmological examination was performed with special attention to the coloboma site, size, conjunctival fornix, cutaneous pterygium, and corneal transparence as well as lower eyelid position and conformity. Three-dimensional orbital computed tomography scan examination was also used for bony defects. All patients were photographed. The guardians of the children provided written informed consent for the publication of the eye photos. The symptomatology, physical findings, detailed ophthalmic examination results, and ocular complications were recorded on an itemized data collection form.

Classification and grading of ocular involvement

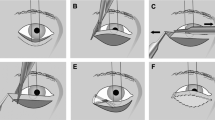

We considered four components of ocular involvement important in the assessment of the eyes, including upper eyelid defect, symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium, corneal complications (opacification, neovascularization, keratinization, and limbal stem cell deficiency), and lower eyelid ectropion; each component was graded on a scale from 0 to 3, depending on the severity of involvement. The following classification and grading systems were used to evaluate the nature of the ocular complications in these patients.

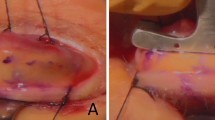

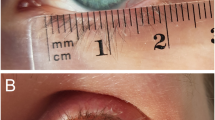

The extent of upper eyelid defect was graded 0 when no defect appeared, grade 1 (mild) when less than one-third of the eyelid was affected, grade 2 (moderate) when greater than one-third but less than one half of the eyelid was affected, and grade 3 (severe) when more than one half the eyelid was affected (Figures 1a–c). The extent of symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium was scored from 0 through 3, where 0=no symblepharon, 1=symblepharon and cutaneous pterygium confined to the corneal limbus, 2=symblepharon and cutaneous pterygium extending up to the pupil margin, and 3=symblepharon and cutaneous pterygium extending beyond the pupil into the central cornea (Figures 1d–f). The severity of corneal complications was also graded as unaffected, mild, moderate, and severe by examining the corneal photographs in a masked fashion. Grade 0=clear cornea, grade 1 (mild)=corneal opacity and keratinization localized at the periphery less than two continuous hours; grade 2 (moderate)=corneal opacity and cutaneous pterygium less than four continuous hours; and grade 3 (severe)=extensive opacity, cutaneous pterygium, keratinization, or neovascularization with more than four continuous hours (Figures 1d–f). The extent of lower eyelid ectropion was graded 0 when no ectropion appeared, grade 1 (mild) when less than one-third of the lower eyelid exhibited ectropion, grade 2 (moderate) when greater than one-third but less than two-thirds of the eyelid exhibited ectropion, and grade 3 (severe) when more than two-thirds of the lower eyelid exhibited ectropion (Figure 2).

Representative grading of the severity of upper eyelid defect (a–c), symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium and corneal complication (d–f). Upper eyelid defects were shown for (a) grade 1, mild; (b) grade 2, moderate; and (c) grade 3, severe. The symblepharon, cutaneous pterygium, and corneal involvement were shown for (d) grade 1, mild; (e) grade 2, moderate; and (f) grade 3, severe complications.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 19.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. The Spearman correlation coefficient (r) (two-tailed) was calculated to assess the relationship between upper eyelid defect, symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium, corneal complication, and ectropion. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The inter/intra-observer reliability was assessed with Cohen’s kappa (κ).

Results

A total of 85 eyes of 59 patients were included in this study. There were 36 male and 23 female patients; the median age at the time of presentation was 3 years (ranging from 1 month to 33 years old), and 42 of the patients were children under 6 years old. Twenty-six cases presented bilaterally, and unilateral presentation was found in 33 cases.

All the cases presented upper eyelid coloboma, eyebrow deformities, and a wedge-shaped anterior hairline extension. Computed tomography image revealed bony clefts only in two of the cases. Five eyes presented with cryptophthalmos, which were not graded because of the lack of a cornea and deformity of the lids. The four main components of ocular involvement were assessed in the remaining 80 eyes.

A detailed summary of the four evaluated components is shown in Table 1. Among the 80 eyes, upper eyelid defect was observed in all cases, 12 (15.0%) eyes were classified as grade 1 (Figure 1a), 25 (31.3%) eyes as grade 2 (Figure 1b), and the remaining 43 (53.8%) eyes as grade 3 (Figure 1c). Moderate to severe (grade 2 or 3) eyelid defect was present in 68 eyes (85.0%). Symblepharon with cutaneous pterygium was observed in 76 (95.0%) eyes. Twelve (15.0%) eyes were classified as grade 1 (Figure 1d), 26 (32.5%) eyes as grade 2 (Figure 1e), and the remaining 38 (47.5%) eyes as grade 3 (Figure 1f). Among the 80 eyes examined, only 4 (5.0%) eyes had no corneal involvement, 12 (15.0%) eyes were classified as grade 1 (Figure 1d), 24 (30.0%) eyes as grade 2 (Figure 1e), and 40 (50.0%) eyes as grade 3 (Figure 1f). Lower eyelid ectropion was found in 34 eyes, nearly half of all the 80 eyes (42.5%); 13 (16.3%) eyes were classified as grade 1 (Figure 2a), 13 (16.3%) eyes as grade 2 (Figure 2b), and 8 (10.0%) eyes as grade 3 (Figure 2c).

The inter/intra-observer reliability was assessed with Cohen’s kappa (κ). The κ-values for inter- and intra-observer were 0.822 and 1, respectively, for upper eyelid defect; 0.854 and 1 for symblepharon; 0.858 and 0.858 for corneal involvement; and 1 and 1 for lower eyelid.

Correlation of upper-lid defect with symblepharon, corneal complications, and lower-lid ectropion

Further statistical analyses showed a strong correlation between the extent of upper eyelid defect and severity of symblepharon, corneal complications, and lower eyelid ectropion (upper eyelid defect and symblepharon, r=0.844, P<0.0001; upper eyelid defect and corneal complication, r=0.866, P<0.0001; upper eyelid defect and ectropion, r=0.629, P<0.0001; symblepharon and corneal complication, r=0.971, P<0.001; Table 2). Indeed, we identified a total of 67 eyes with such a strong topographic and spatial correlation. Figure 1 illustrates three such cases.

Conclusion

Congenital eyelid colobomas either can occur as an isolated anomaly or can be associated with multiple ocular and systemic anomalies. These anomalies include craniofacial clefts,1, 2, 3, 4 Goldenhar,10, 11 Treacher-Collins,12 Delleman syndromes,13 frontonasal dysplasia,14 Fraser,15, 16 and nasopalpebral lipoma coloboma syndromes.17 Upper eyelid defect in Tessier number 10 clefts is typically located in the middle third of the upper eyelid and is usually combined with ocular anomalies, including symblepharon, cutaneous pterygium, and corneal complications (opacification, neovascularization, keratinization, and limbal stem cell deficiency), eyebrow deformity, lower eyelid ectropion, cryptophthalmos, and bony defect. We found 100% cases had upper eyelid defect, eyebrow deformities, and a wedge-shaped anterior hairline extension, 95% cases had symblepharon, 95.0% cases had corneal complications, and 42.5% cases had lower eyelid ectropion. Five cases presented with cryptophthalmos, which was also reported in several articles.18, 19 Although bony clefts were described when the disease was first reported,1 we only found two cases with bony clefts in our study, indicating that the bony cleft is not a presentation as common as other ocular anomalies.

The evaluation of ocular involvement in these patients is extremely important because ocular involvement often represent the only long-term complication of Tessier number 10 clefts. There is currently no established method for evaluating the spectrum of ocular manifestations arising from these diseases. In this study, we detailed the characteristic ocular manifestations in patients with Tessier number 10 clefts and developed a grading system to assess more objectively the extent and severity of four main components of this ocular involvement. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically attempted to improve and standardize the evaluation of ocular involvement in Tessier number 10 clefts.

As we set out to develop a grading system that could be used easily by ophthalmologists, we identified components that were important and could be evaluated easily by simple examination. We used a simple method for grading the severity of these involvement; the components were assigned scores that reflected whether involvement was mild, moderate, or severe. This grading method was judged to be easy and convenient in evaluating 85 eyes from 59 patients.

Our analyses disclosed that the extent of corneal complications and symblepharon was most significantly correlated with upper eyelid defect (Table 2). On the one hand, the relationship between the two is purely correlative and not causative, because the three involvement appeared simultaneously in some of the babies in our cases. On the other hand, it is more plausible that the relationship between the two is causative with time. This interpretation was supported by the finding that in some of the cases, especially adults, patients presented with total corneal opacity, keratinization, and neovascularization, which may have been caused by exposure of the eyelid defect without correction in the early stages.

Therefore, we speculate that upper eyelid defect combined with symblepharon and corneal complications were the main ocular involvement and characteristics in the Tessier number 10 clefts, which could have appeared at the same time just after birth. If the eyelid defect and symblepharon were not corrected at an early stage, corneal complications would be increasingly severe with time because of the exposure and reduced protection of the eyelid and tear film, especially in patients with severe eyelid defect.

We also found that 34 eyes presented with lower eyelid ectropion, which has never been reported in Tessier 10 clefts previously. Because Tessier number 10 clefts are rare, and there were only several case reports, ectropion was neither presented nor neglected in their cases. In this study, the largest report of Tessier number 10 clefts until now, almost half of the cases, presented with lower eyelid ectropion. Therefore, lower eyelid ectropion should be included in the features of the Tessier number 10 clefts. Furthermore, the severity of ectropion also correlated with the extent of the upper eyelid defect and the symblepharon and corneal complications. We propose that the reason may be loss of the lateral canthus ligament without upper eyelid supporting traction.

The use of a standardized method for grading the extent and severity of ocular involvement in patients with Tessier number 10 clefts offers significant advantages. First, the grading method introduced here can be used in the initial evaluation, follow-up, and monitoring of ocular complications. The grading method ensures that specialists, as well as nonspecialized ophthalmologists, can detect important ocular complications. Second, The grading method may help ophthalmologists to make a better decision on appropriate surgical management and predict the outcome of the treatment. Third, various eyelid reconstruction and ocular surface reconstructive procedures have been used to treat ocular manifestations in this kind of patient. However, many of the reported studies are nonrandomized case series without control arms, and because there is currently no standardized method for grading ocular involvement in these patients, it is difficult to compare the method and treatment outcomes of these studies. Our grading system provides a standardized method for evaluating patients before surgical procedures.

In summary, this study presents a variety of ocular manifestations in a large series of Tessier number 10 clefts, including previously unreported manifestations, and establishes an effective grading system to evaluate Tessier number 10 clefts. The use of this grading system as a new objective method to grade the severity of this disease may help to establish standard procedures and predict the long-term post-op prognosis for the patients.

References

Tessier P . Anatomical classification of facial, cranio-facial and latero-facial clefts. J Maxillofac Surg 1976; 4: 69–92.

Fan X, Shao C, Fu Y, Zhou H, Lin M, Zhu H . Surgical management and outcome of Tessier Number 10 clefts. Ophthalmology 2008; 115: 2290–2294.

Ortube MC, Dipple K, Setoguchi Y, Kawamoto Jr HK, Demer JL . Ocular manifestations of oblique facial clefts. J Craniofac Surg 2010; 21: 1630–1631.

Lee HM, Noh TK, Yoo HW, Kim SB, Won CH, Chang SE et al. A wedge-shaped anterior hairline extension associated with a tessier number 10 cleft. Ann Dermatol 2012; 24: 464–467.

Grover AK, Chaudhuri Z, Malik S, Bageja S, Menon V . Congenital eyelid colobomas in 51 patients. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2009; 46: 151–159.

Lodhi AA, Junejo SA, Khanzada MA, Sahaf IA, Siddique ZK . Surgical outcome of 21 patients with congenital upper eyelid coloboma. Int J Ophthalmol 2010; 3: 69–72.

Ankola PA, Abdel-Azim H . Congenital bilateral upper eyelid coloboma. J Perinatol 2003; 23: 166–167.

Seah LL, Choo CT, Fong KS . Congenital upper lid colobomas: management and visual outcome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18: 190–195.

Hashish A, Awara AM . One-stage reconstruction technique for large congenital eyelid coloboma. Orbit 2011; 30: 177–179.

Gorlin RJ, Jue KL, Jacobson U, Goldschmidt E . Oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia. J Pediatr 1963; 63: 991–999.

Sugar HS . The oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia syndrome of Goldenhar. Am J Ophthalmol 1966; 62: 678–682.

Jackson IT . Reconstruction of the lower eyelid defect in Treacher Collins syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg 1981; 67: 365–368.

Delleman JW, Oorthuys JW . Orbital cyst in addition to congenital cerebral and focal dermal malformations: a new entity? Clin Genet 1981; 19: 191–198.

Sedano HO, Cohen Jr MM, Jirsek J, Gorlin RJ . Frontonasal dysplasia. J Pediatr 1970; 76: 906–913.

Thomas IT, Frias JL, Felix V, Sanchez de Leon L, Hernandez RA, Jones MC . Isolated and syndromic cryptophthalmos. Am J Med Genet 1986; 25: 85–98.

Saleh GM, Hussain B, Verity DH, Collin JR . A surgical strategy for the correction of Fraser syndrome cryptophthalmos. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 1707–1712.

Bock-Kunz AL, Lyan DB, Singhal VK, Grin TR . Nasopalpebral lipoma-coloboma syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 2000; 118: 1699–1701.

Lessa S, Nanci M, Sebastiá R, Flores E . Two-stage reconstruction for eyelid deformities in partial cryptophthalmos. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2011; 27: 282–286.

Nouby G . Congenital upper eyelid coloboma and cryptophthalmos. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2002; 18: 373–377.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China grant (81370992, 81570812, and 81500765), National High Technology Research and Development Program (863 Program, 2015AA020311), Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning Found (20144Y0221), and the Shanghai Young Doctor Training Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, C., Lu, W., Li, J. et al. Manifestation and grading of ocular involvement in patients with Tessier number 10 clefts. Eye 31, 1140–1145 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.39

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.39