Abstract

Purpose

It is vital that surgeons undertaking oculoplastic procedures are able to show that the surgery they perform is of benefit to their patients. Not only is this fundamental to patient-centred medicine but it is also important in demonstrating cost effectiveness. There are several ways in which benefit can be measured, including clinical scales, functional ability scales, and global quality-of-life scales. The Glasgow benefit inventory (GBI) is an example of a patient-reported, questionnaire-based, post-interventional quality-of-life scale that can be used to compare a range of different treatments for a variety of conditions.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was undertaken using the GBI to score patient benefit from four commonly performed oculoplastic procedures. It was completed for 66 entropion repairs, 50 ptosis repairs, 41 ectropion repairs, and 41 external dacryocystorhinostomies (DCR). The GBI generates a scale from −100 (maximal detriment) through zero (no change) to +100 (maximal benefit).

Results

The total GBI scores of patients undergoing surgery for entropion, ptosis, ectropion, and external DCR were: +25.25 (95% CI 20.00–30.50, P<0.001), +24.89 (95% CI 20.04–29.73, P<0.001), +17.68 (95% CI 9.46–25.91, P<0.001), and +32.25 (95% CI 21.47–43.03, P<0.001), respectively, demonstrating a statistically significant benefit from all procedures.

Conclusion

Patients derived significant quality-of-life benefits from the four most commonly performed oculoplastic procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health service providers around the world are increasingly called upon to justify the allocation of finite resources to an ever expanding number of health technologies (medicines, procedures, and health-promotion interventions). This leads to rigorous examination of cost effectiveness, a role undertaken for the National Health Service (NHS) in England and Wales by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). The unit of effectiveness used by NICE is the ‘quality-adjusted life year’ (QALY) (http://www.nice.org.uk/media/68D/29/The_guidelines_manual_2009_-_Chapter_7_Assessing_cost_effectiveness.pdf). QALYs are an overall measure of health outcome that weigh the life expectancy of a patient against an estimate of their health-related quality-of-life (HRQL). Typically NICE considers a health technology costing below £20 000 per QALY to be ‘cost-effective’. To date, the only oculoplastic procedure to have been the subject of a NICE appraisal is endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR), which was approved (http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11027/30616/30616.pdf).

The majority of health-care provision by the NHS in England is, at present, the responsibility of regional commissioning bodies known as primary care trusts (PCTs) who purchase primary and secondary care on behalf of their patients. Collectively, PCTs spend around 80% of the NHS budget. In commissioning services PCTs typically follow the advice published by NICE, but outside these guidelines are free to make local judgements about funding priorities. As with NICE, these are cost-effectiveness decisions, and in the field of oculoplastic surgery it is increasingly common for PCTs to set rigid clinical criteria before agreeing to fund treatment. Examples include a demonstrable visual field defect with ptosis or dermatochalasis, or chronicity and discomfort with meibomian cysts. Many PCTs are implementing lists of ‘low priority procedures’ that they will not fund, and which increasingly include oculoplastic procedures.

The use of rigid criteria in the allocation of health resources is controversial. While it reflects a desire to place simple, consistent conditions on funding decisions, it can be at odds with the ethos of patient-centred medicine. As clinicians it is vital that we can demonstrate a genuine benefit to our patients, both ethically and financially, yet patient benefit can be difficult to measure. The clinician’s perception of success may differ from that of the patient, and patients themselves can vary from one to another given apparently similar functional outcomes from surgery.1 The height of the lid after ptosis surgery, for example, may be a surgeon’s measure of success, but previous studies have shown a surprising mismatch between objective clinical assessment and subjective benefit.2 Furthermore, it is the patients who report the greatest subjective preoperative functional impairment who derive the greatest quality-of-life improvements from surgery, rather than those with the greatest clinical impairment.3

Measuring patient benefit from medical interventions has been the subject of extensive research. The various scoring systems that have been developed tend to fall into one or more of three broad categories: clinical scales, activities of daily living/functional ability scales, and global quality-of-life scales. Clinical scales typically rely on objective, physical outcome measures, whereas the functional and quality-of-life scales typically rely on subjective patient-reported responses obtained using questionnaires. Over 800 examples of such questionnaire-based tools can now be found on the Mapi Institute ‘Quality of Life Instruments Database’ (http://www.mapi-institute.com). In devising this study, we examined the strengths and weaknesses of some of the most widely used quality-of-life questionnaires, including the Sickness Impact Factor4, the Nottingham Health Profile5, the Euroqol6, the Medical Outcomes Short-Form 36 (SF-36)7, and the Glasgow Benefit Inventory (GBI)8.

Of these, we concluded that the GBI was the most suitable for our study. The GBI was initially developed for otorhinolaryngological interventions, and the original paper was used to compare patient benefit from cochlear implant, middle ear surgery (for hearing and for infection), rhinoplasty, and tonsillectomy. However, a major strength of the GBI is its ability to compare a range of different treatments for a variety of conditions, and across diverse demographic and cultural groups. It also benefits from being post-interventional quick and easy to administer by telephone or post, focused on change (rather than taking preoperative and postoperative measures and subtracting one from the other), and its use has been validated for oculoplastic procedures (DCR9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and botulinum toxin for blepharospasm14).

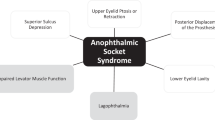

In this study, we have used the GBI to assess patient benefit from four commonly performed oculoplastic operations: ptosis repair, entropion repair, ectropion repair, and DCR. Although not normally life- or vision-threatening, the symptoms associated with ptosis, entropion, ectropion, and nasolacrimal obstruction are often distressing to patients with a major adverse impact to HRQL. The visual disability associated with epiphora, for example, is often underestimated. One study comparing 14 measures of vision-dependent activities of daily living (VF-14) in patients with epiphora and those awaiting second eye cataract surgery found that those with epiphora performed worse in 12 out of 14 tasks.15 The study recorded moderate to major difficulty in reading in 48% of patients with epiphora compared with 26% in those patients with cataract.

To date, the oculoplastic procedure most widely investigated for its quality-of-life benefits is DCR. Four studies have been published in peer-reviewed journals reporting GBI outcomes for DCR. Although these all take slightly different approaches, the results for external DCR range from +18.5 9 to +23.2,10 and for endonasal DCR from +16.8 10 to +52.0.11 Elsewhere in the literature, satisfaction with botulinum toxin is reported as +29.2 for blepharospasm,14 and +38.0 for spasmodic dysphonia,16 and with otorhinolaryngological surgery at +20.0 for rhinoplasty,17 +11.3 for septoplasty,18 and +23.0 for functional endoscopic sinus surgery.19

Materials and methods

The GBI consists of 18 questions with responses scored on a five-point Likert scale, from a large deterioration through to a large improvement in health status. The questions assess the patient’s general perception of well-being, with psychological, social, and physical subscales. Post hoc analysis converts the results of the questionnaire to a score from −100 (maximal detriment) through zero (no change) to +100 (maximal benefit). A full list of the GBI questions is provided in Figure 1.

The questionnaire was completed during a telephone interview conducted by a member of the study team, a process that typically took 5–10 min. Subjects were identified from the theatre log at Maidstone hospital, using consecutive patients under the care of a single consultant oculoplastic surgeon (CAJ) who underwent surgery between April 2008 and April 2010. Verbal consent was obtained before proceeding with the questionnaire, and the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Maidstone Hospital NHS Trust.

Suitable patients were selected for four commonly performed oculoplastic procedures: entropion repair, ptosis repair, ectropion repair, and external DCR. The number of appropriate subjects was 79, 63, 50, and 50, respectively, of which the GBI questionnaire was successfully completed for 66, 50, 41, and 41, respectively (representing a completion rate of 85, 79, 82, and 82%). The mean age (with ranges) of patients undergoing surgery was 78.4 (53–94), 64.0 (20–89), 75.6 (56–100), and 67.4 (20–90) years old, respectively, and the proportion of men was 62, 52, 63, and 27%. The majority of cases where the questionnaire was not completed related to incorrect contact details and an inability to reach the patient by telephone.

Results

The total GBI scores of patients undergoing surgery for entropion, ptosis, ectropion, and external DCR were +25.25 (95% CI 20.00–30.50, P<0.001), +24.89 (95% CI 20.04–29.73, P<0.001), +17.68 (95% CI 9.46–25.91, P<0.001), and +32.25 (95% CI 21.47–43.03, P<0.001), respectively, demonstrating a statistically significant benefit from all procedures (Table 1). Confidence intervals were calculated using a Student’s t-distribution, Instat 3 biostatistics (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Subscale analysis groups responses to certain questions to give further information about the nature of the benefit the patient derived. These subscales are general impact (psychological benefit to self), physical impact (overall physical health), and social impact (support from others). The mean scores for entropion, ptosis, ectropion, and external DCR using the general subscale were +31.12, +38.58, +21.85, and +37.80, respectively, using the physical subscale were +17.43, −7.67, +4.47 and +15.85, respectively, and using the social subscale were +9.09, +2.47, +14.23 and +26.42, respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

Patients report levels of satisfaction with these four common oculoplastic procedures that compare favourably with other treatments that have been studied using the GBI. Our results show slightly higher levels of patient benefit from external DCR compared with previous reports in the literature (+32.25 compared with +18.59 and +23.210).

Within the overall GBI score, the scores achieved on the general, physical, and social subscales demonstrate some important differences between the four procedures. While the general score, reflecting overall psychological benefit, is reasonably consistent, the social and physical scores are more variable.

The social subscale records support received from family and friends, and suggests a large benefit from external DCR, more modest improvements from correction of ectropion and entropion, and relatively little benefit from ptosis repair. This may reflect the fact that chronically watering eyes are more socially stigmatising than eyelid malposition, with some patients reporting that they were thought of as being emotionally labile as they were seen to be ‘crying all the time’. Similarly, patients suffering with the red, crusty lids and recurrent conjunctivitis of ectropion and entropion felt they were perceived as having poor personal hygiene. Improved watering and healthy-looking eyes may in turn have improved a patients’ perception of their interaction with family and friends by making them feel less self-conscious. The social subscale of the GBI specifically reflects the patients’ perception of how others respond to them, whereas the general subscale reflects the way that the patients themselves interact with others. Overall, the quality of social interaction will be a combination of these factors, and on this measure ptosis patients reported much more positive results, feeling both less self-conscious about how others saw them, and more self-confident about themselves.

One of the potential weaknesses of the GBI score is that a negative score may not indicate a genuinely adverse outcome from the surgery. On the social and general subscales, for example, much relies on the personality of individual patients, with those who did not find the condition adversely affecting them socially or psychologically before surgery tending to report less significant improvements after. But perhaps more importantly two out of three questions on the physical subscale ask about additional treatment or additional health problems for any reason since their surgery, and which could give a negative score even when completely unrelated to the lid/lacrimal surgery. Together, these factors probably account for the negative minimum scores we have demonstrated in all procedures, and for the negative mean score for physical health following ptosis surgery. It is our impression that these negative scores do not tend to reflect individually poor outcome in terms of postoperative complications of failed surgery.

Analysing the mean, median, and SD for the four procedures demonstrates some interesting patterns (Table 1, Figure 2). Benefit from ectropion surgery appears to be skewed by a small group of patients with a particularly negative experience (large positive skew), and entropion and DCR by a larger group of patients with more positive experiences (small negative skew). Outcome from ptosis surgery is quite consistent (small SD), and from DCR quite variable (large SD).

Although the GBI offers a straightforward, flexible tool for measuring patient benefit, questionnaires like these suffer from some inherent limitations. Subjective responses offer no measure of consistency and may be influenced by factors such as the style of interviewer, the time of day, or concurrent activities. There is also the suspicion that responses may owe as much to the personality of the respondent as to the effect of the procedure. It is expected, however, that such biases would be equally represented in all groups allowing a valid comparison.

As medical practitioners, we aim to improve the quality of our patients’ lives. A significant body of evidence points to the mismatch between objective clinical impairment and subjective HRQL.2 In patient-centred medicine, and with non-lifesaving interventions, high-quality data to demonstrate patient benefit are essential. Our study using the GBI shows significant improvements in quality-of-life from the four oculoplastic procedures we have examined, and subjective benefit to the patient should be an important consideration when appraising the value of a given intervention. We believe that greater use of patient benefit questionnaires such as GBI could contribute positively to decision making when PCTs commission services for their patients. Furthermore, patient benefit questionnaires offer a potentially useful measure of performance that could be used to compare outcomes from surgery against recognised standards in clinical audit.

In the NHS in England 2009–2010, the volume of surgery undertaken of the four procedures we have examined was as follows: entropion repair 5449, ptosis repair 5445, ectropion repair 5741, and DCR 4380 (http://www.hesonline.nhs.uk/Ease/servlet/AttachmentRetriever?site_id=1937&file_name=d:/efmfiles/1937/Accessing/DataTables/Annualinpatientrelease2010/MainOp4_0910.xls&short_name=MainOp4_0910.xls&u_id=8920). Almost all of these procedures were performed as day cases, and with the exception of DCR almost exclusively under local anaesthesia. As such, they are relatively low-cost interventions that we have shown bring genuine benefits physically, socially, and psychologically to our patients. Our results show that this group of conditions should not be considered purely within the realms of cosmetic surgery, and we hope that this study can contribute to well-informed commissioning of oculoplastic procedures in the future.

References

Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG . Measuring quality of life: is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ 2001; 322: 1240–1243.

Leong SC, Karkos PD, Burgess P, Halliwell M, Hampal S . A comparison of outcomes between nonlaser endoscopic endonasal and external dacryocystorhinostomy: single-center experience and a review of British trends. Am J Otolaryngol 2010; 31: 32–37.

Federici TJ, Meyer DR, Lininger LL . Correlation of the vision-related functional impairment associated with blepharoptosis and the impact of blepharoptosis surgery. Ophthalmology 1999; 106: 1705–1712.

Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS . The Sickness Impact Profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care 1981; 19: 787–805.

Hunt SM, McEwen J, McKenna SP . Measuring health status: a new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. J R Coll Gen Pract 1985; 35: 185–188.

The EuroQol Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990; 16: 199–208.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD . The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992; 30: 473–483.

Robinson K, Gatehouse S, Browning GG . Measuring patient benefit from otorhinolarynhological surgery and therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1996; 105: 415–422.

Feretis M, Newton JR, Ram B, Green F . Comparison of external and endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. J Laryngol Otol 2009; 123: 315–319.

Bakri SJ, Carney AS, Robinson K, Jones NS, Downes RN . Quality of life outcomes following dacryocystorhinostomy: external and endonasal laser techniques compared. Orbit 1999; 18: 83–88.

Smirnov G, Tuomilehto H, Kokki H, Kemppainen T, Kiviniemi V, Nuutinen J et al. Symptom score questionnaire for nasolacrimal duct obstruction in adults - a novel tool to assess the outcome after endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Rhinology 2010; 48: 446–451.

Spielmann PM, Hathorn I, Ahsan F, Cain AJ, White PS . The impact of endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR), on patient health status as assessed by the Glasgow benefit inventory. Rhinology 2009; 47: 48–50.

Ho A, Sachidananda R, Carrie S, Neoh C . Quality of life assessment after non-laser endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Clin Otolaryngol 2006; 31: 399–403.

MacAndie K, Kemp E . Impact on quality of life of botulinum toxin treatments for essential blepharospasm. Orbit 2004; 23: 207–210.

Kafil-Hussain N, Khooshebah R . Clinical research, comparison of the subjective visual function in patients with epiphora and patients with second-eye cataract. Orbit 2005; 24: 33–38.

Bhattacharyya N, Tarsy D . Impact on quality of life of botulinum toxin treatments for spasmodic dysphonia and oromandibular dystonia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001; 127: 389–392.

Draper MR, Salam MA, Kumar S . Change in health status after rhinoplasty. J Otolaryngol 2007; 36: 13–16.

Calder NJ, Swan IR . Outcomes of septal surgery. J Laryngol Otol 2007; 121: 1060–1063.

Salhab M, Matai V, Salam MA . The impact of functional endoscopic sinus surgery on health status. Rhinology 2004; 42: 98–102.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Parts of this work have previously been presented at academic meetings.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, H., Jyothi, S., Mahroo, O. et al. Patient-reported benefit from oculoplastic surgery. Eye 26, 1418–1423 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2012.188

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2012.188

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

8-0 polyglactin 910 suture in entropion repair: long term follow up and rates of recurrence

Eye (2023)

-

Exploring correlations between change in visual acuity following routine cataract surgery and improvement in quality of life assessed with the Glasgow Benefit Inventory

Eye (2018)

-

Assessment of patient-reported outcome and quality of life improvement following surgery for epiphora

Eye (2017)

-

Anterior approach white line advancement: technique and long-term outcomes in the correction of blepharoptosis

Eye (2017)

-

Long term patient-reported benefit from ptosis surgery

Eye (2015)