Abstract

Oxidized LDL (OxLDL), a causal factor in atherosclerosis, induces the expression of heat shock proteins (Hsp) in a variety of cells. In this study, we investigated the role of CD36, an OxLDL receptor, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in OxLDL-induced Hsp70 expression. Overexpression of dominant-negative forms of CD36 or knockdown of CD36 by siRNA transfection increased OxLDL-induced Hsp70 protein expression in human monocytic U937 cells, suggesting that CD36 signaling inhibits Hsp70 expression. Similar results were obtained by the inhibition of PPARγ activity or knockdown of PPARγ expression. In contrast, overexpression of CD36, which is induced by treatment of MCF-7 cells with troglitazone, decreased Hsp70 protein expression induced by OxLDL. Interestingly, activation of PPARγ through a synthetic ligand, ciglitazone or troglitazone, decreased the expression levels of Hsp70 protein in OxLDL-treated U937 cells. However, major changes in Hsp70 mRNA levels were not observed. Cycloheximide studies demonstrate that troglitazone attenuates Hsp70 translation but not Hsp70 protein stability. PPARγ siRNA transfection reversed the inhibitory effects of troglitazone on Hsp70 translation. These results suggest that CD36 signaling may inhibit stress-induced gene expression by suppressing translation via activation of PPARγ in monocytes. These findings reveal a new molecular basis for the anti-inflammatory effects of PPARγ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Expression of Hsp70 protein is increased in atherosclerotic lesions, which correspond to sites of LDL oxidation and/or of oxidized LDL (OxLDL) accumulation (Roma and Catapano, 1996; Kanwar et al., 2001; Han et al., 2003; Metzler et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2004). In addition, plasma concentrations of Hsp70 were shown to increase in patients with cardiovascular disease, including atherosclerosis (Park et al., 2006). Treatment of macrophages with OxLDL significantly increased Hsp70 concentrations in culture supernatants, which could induce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and IL-12 secretion in naїve macrophages (Svensson et al., 2006). The effect of OxLDL on cytokine production can be blocked by the inhibition of Hsp70 transcription, inhibition of Hsp70 secretion, or by the use of Hsp70 neutralizing antibodies. These results suggest that OxLDL-mediated Hsp70 expression may play a role in human vascular diseases.

CD36, a major OxLDL receptor, is an 88-kDa cell surface glycoprotein consisting of two hydrophobic domains located at the N- and C-termini of the protein (Febbraio et al., 2001). CD36 was originally identified as a platelet membrane glycoprotein and a receptor for thrombospondin (TSP-1) (Li et al., 1993). CD36 expression has been identified in monocytes/macrophages, microvascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, adipocytes, skeletal muscle, dendritic cells, and breast and retinal pigment epithelium (Febbraio et al., 2001). CD36 binds to TSP-1, OxLDL, apoptotic cells, collagen, Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes, long-chain fatty acids, anionic phospholipids, and LDL modified by monocyte-generated reactive nitrogen species (Febbraio et al., 2001). CD36 also recognizes native lipoproteins HDL, LDL and VLDL (Calvo et al., 1998).

OxLDL binding to CD36 induces the activation of PPARγ, a member of a nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) (Jiang et al., 1998; Tontonoz et al., 1998). CD36-mediated endocytosis internalizes PPARγ ligands and activators and lipid moieties of OxLDL (Nicholson et al., 1995). Subsequent ligand-dependent sumoylation of the PPARγ inhibits the signal-dependent removal of nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR), leading to the trans-repression of inflammatory response genes (Ogawa et al., 2005; Pascual et al., 2005). Thus, OxLDL suppresses pro-inflammatory responses by activating PPARγ, and at the same time, stimulates production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by inducing Hsp70 expression. Although the ability of OxLDL to induce Hsp70 expression has been clearly demonstrated, the molecular mechanism by which CD36 and PPARγ regulates OxLDL-induced Hsp70 expression has not yet been established. In the present study, using human monocytic U937 and breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells that express CD36 and PPARγ (Elstner et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2004), we investigated the roles for CD36 and PPARγ in OxLDL-induced Hsp70 expression. Our findings demonstrate that OxLDL binding to CD36 inhibits Hsp70 gene expression at the translational level in monocytes through a PPARγ-dependent pathway.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Culture reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). OxLDLs (RP-047) and normal LDL (RP-031) were obtained from Intracel (Frederick, MD). PMA and all trans retinoic acid (ATRA) were purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). Nitrocellulose membranes and the antibody detection kit (ECL plus) were obtained from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). 15- Deoxy-Δ12,14-Prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), ciglitazone, troglitazone, and prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) were obtained from BioMol Res. (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Anti-human CD36 mAbs, SMO and FA6-152, were from Serotec (Raleigh, NC) and Immunotech (Marseille Cedex, France), respectively. Anti-human PPARg polyclonal Ab was provided by Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Beverly, MA). Anti-Hsp70 mAb was obtained from the Stressgen (San Diego, CA). Anti-human α-actin mAb was from Sigma-Aldrich Co (St. Louis, MO). Goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody was from Dinona (Seoul, Korea).

DNA constructs and transfection

Human CD36 cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. Brian Seed (Massachusetts General Hospital, Department of Molecular Biology, Boston, MA). Dominant negative CD36 constructs were obtained by PCR using 10 pmol of sense primer I (5'-GGAATTCATGGGCTGTGACCGGAACTGTG-3), sense primer II (5'-CCCAAGCTTATGGGGCTCATCGCTGGGGCTG-3'), antisense primer I (5'-GCTCTAGATTATTTTATTGTTTTCGATCTGCATG-3'), and antisense primer II (5'-GCTCTAGATTAGCATGCACAATATGAAATCATAAAAG-3'). CD36 ΔN, a N-terminus truncated form of CD36, DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using sense primer II and antisense primer I and then was subcloned into the HindIII and Xba I sites of a stable expression vector, pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). In this construct, an initiation codon has been inserted at position 7 so as to initiate translation just before the hydrophobic domain at the N-terminus of CD36. CD36 ΔC, a C-terminus truncated form of CD36, DNA fragment was amplified by PCR using sense primer I and antisense primer II and then was subcloned into the EcoRI and Xba I sites of a stable expression vector, pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). In CD36 ΔC, a stop codon has been inserted at position 462 to terminate translation after the hydrophobic domain at the C-terminus of the protein. CD36 ΔN/C, N-terminus and C-terminus truncated form of CD36, DNA fragment was constructed as previously described (Lee et al., 2006). All sequences of these constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. 293T cells were transiently transfected with these constructs using electroporation. As a control, pcDNA3.1 vector only was also transfected. 2 days after transfection into human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells, surface expression of CD36 variants was confirmed by flow cytometry using a monoclonal anti-human CD36 antibody FA6-152 and an FITC conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody as previously described (Lee et al., 2004). The anti-CD36 antibody recognizes an epitope in the extracellular portion of CD36. Stable DNA transfection with these constructs DNAs was also performed in U937 cells using electroporator (Invitrogen). Stable transfectants were selected in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 0.6 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen) for 4 weeks. Resistant clones were selected and then their cell surface expression levels of wild type and mutant CD36 were examined as described above.

Cell culture and heat shock conditions

U937 cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen) in 5% CO2 at 37℃. For cultures of dominant-negative CD36 transfectants, G418 were added to the complete RPMI medium at a concentration of 0.6 mg/ml. MCF-7 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and antibiotics (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY). To induce Hsp70 synthesis, culture plates containing U937 cells were wrapped tightly with parafilm and immersed in a water bath for 20 min at 42℃.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed for detecting Hsp70 protein expression as previously described (Choi et al., 2007). Sparse or confluent cultures were incubated with OxLDL (80 µg/ml) for different time periods (up to 8 h). Cells were lysed in NP40 lysis buffer [1% Nonidet P40, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05M Tris (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA]. Equal amounts of protein from the different samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, after the addition of β-mercaptoethanol (2%), glycerol, and bromophenol blue. Cell lysates were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with blocking solution (3% BSA in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20), and incubated with Hsp70 antibodies (1:1,000 dilution) while they were shaken in TBS buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 for 2 h at room temperature. After incubation with primary antibody, the blot was incubated with an appropriate secondary anti-IgG-HRP conjugate. The membrane was washed five times for 5 min in Tris-buffered saline, 0.05% Tween 20, and developed with ECL chemiluminescent substrate (Amersham Biosciences).

Northern blot analysis

Expression of Hsp70 mRNA was determined by Northern blot analysis as previous described (Lee et al., 2004). Total RNA was extracted from U937 cells with the TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Rockville, MR). Total RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically, and 20 µg RNA was separated in 0.8% formaldehyde/agarose gels and transferred to nylon membranes in 10× SSC buffer [1.5 M NaCl, 0.15 M C6H5O7Na·H2O (pH7.0)] by capillary action. Hsp70 cDNA probe was prepared by cutting pcDNA3.1-Hsp70 plasmid DNA with HindIII and Xba I. As internal control probe, GAPDH cDNA probe was obtained by RT-PCR using forward primer, 5'-TCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGTA-3' and reverse primer, 5'-ATGGACTGTGGTCAGAGTCCTTC-3'. All sequences of the PCR product were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Hsp70 and GAPDH cDNA probes were labeled with [α-32P] dCTP by random primer labeling according to the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI). Blots were hybridized with the 32P-labeled Hsp70 and GAPDH probes for 16 h at 42℃ in hybrizol-N northern hybridization solution (iNtRON biotechnology, Seoul, Korea). After washing once in 1×SSC buffer containing 0.1% SDS at RT for 20 min and three times in 0.2 ×SSC buffer and 0.1% SDS for 20 min at 68℃, the blots were analyzed by exposure to X-Omat AR film (Eastman Kodak Co.) at -70℃.

RNA Interference

The siRNA duplexes were constructed with the following target sequences; CD36, sense (5'-AAGAGGAACTATATTGTGCCTCCTGTCTC-3'); antisense (5'-AAAGGCACAATATAGTTCCTCCCTGTCTC-3'); tyrosinase, sense (5'-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTCCTGTCTC-3'); antisense (5'-AAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAACCTGTCTC-3'). The template oligonucleotides for GAPDH were supplied by Ambion Inc. (Austin, TX). The construction of siRNA directed against control or CD36 was carried out according to the instruction manual provided by the manufacturer (Ambion, Austin, TX). Briefly, two 29-mer DNA oligonucleotides (siRNA template) with 21 nucleotides encoding the siRNA and 8 nucleotides complementary to the T7 promoter primers were synthesized and desalted. In separate reactions, the two siRNA oligonucleotide templates were hybridized to a T7 promoter primer. The 3' ends of the hybridized oligonucleotides were extended by the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase to create double-stranded siRNA transcription templates. The sense and antisense siRNA templates were transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase, and the resulting RNA transcripts were hybridized to create dsRNA. The leader sequences were removed by digesting the dsRNA with a single-strand specific ribonuclease. The resulting siRNA was purified by using glass fiber binding and elution. siRNAs targeting PPARγ coding sequences were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The siRNA sequences were 5'-GUUGACACAGGAUGCCAUUTT-3'. Cells were transfected with 100 nM siRNA duplexes by electroporation (300V, 950 µF) using electroporator (Bio-Rad, Gene Pulser II apparatus). After transfection, medium was changed, and cells were maintained in medium with FBS for 24 h. Depletion of CD36 and PPARγ was confirmed by Western blotting. Cells were then treated with OxLDL or troglitatazone as specified above. The effect of treatment of cells with siRNAs on Hsp70 protein levels was determined by immunoblotting of cell lysates.

Hsp70 stability

U937 cells were cultured at a density of 1 × 106 cells in serum-free RPMI and then heat-shocked for 20 min at 42℃. Cells were then exposed to 5 µg/ml cycloheximide, 5 µM troglitazone, or both after 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 h following heat shock. 8 h after heat shock, cells were lysed and subsequently subjected to Western blot analysis using Hsp70 antibodies as described above.

Results

Binding of OxLDL to CD36 inhibits OxLDL-mediated induction of Hsp70 expression in U937 cells

To determine whether OxLDL induces expression of Hsp70 in U937 cells, cells were treated with various concentrations of OxLDL (10-80 µg/ml) for 8 h. Immunoblot analysis with anti-Hsp70 monoclonal antibody showed that OxLDL readily induced the expression of Hsp70, with OxLDL concentrations ranging from 40 to 80 µg/ml, but not that of Hsp27 (Figure 1A). In contrast, native LDL did not induce the expression of Hsp70 or Hsp27 (data not shown).

OxLDL-mediated activation of CD36 repressed Hsp70 expression. (A) U937 cells were incubated in SFM in the absence or presence of varying concentrations (10-80 µg/ml) of OxLDL for 8 h. Expression levels of Hsp70 and Hsp27 protein were evaluated by Western blot analysis. Results were replicated in three independent experiments. Relative expression levels of Hsp70 are shown as relative intensity of bands measured with a densitometer. Results shown in the lower panel are values relative to the Hsp70 expression level of untreated controls, designated as 100%. (B) CD36ΔN, ΔC, or ΔN/C construct plasmids, having deletions in the N-terminal, C-terminal cytoplasmic domain, or both cytoplasmic domains of CD36, respectively, were transiently transfected into HEK293T cells. Cell surface expression was then verified by flow cytometry using anti-CD36 mAb. (C) U937 mock-transfectants or dominant negative CD36-transfectants were incubated in 1 ml of SFM in the presence of 80 µg of normal LDL, OxLDL or heat-shocked for 20 min at 42℃. After 8 h, expression levels of Hsp70 protein were evaluated by Western blot (WB) analysis. (D) U937 mock transfectants or CD36 ΔN/C transfectants were treated with 1 µM 15d-PGJ2, 5 µM ciglitazone (Cig), and 5 µM troglitazone (Trog) for 8 h. Expression levels of Hsp70 protein were evaluated by Western blot analysis.

To investigate whether the CD36 molecule is involved in OxLDL-mediated induction of Hsp70 expression, we constructed stable expression vectors bearing CD36 dominant negative constructs, containing deletions either in the N-terminal domain (CD36ΔN), the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CD36ΔC), or both cytoplasmic domains of CD36 (CD36ΔN/C). Previously it was shown that the soluble CD36-Ig chimeric molecule containing only the extracellular domain efficiently competed with the intact CD36 for binding of OxLDL (Stewart and Nagarajan, 2006). We confirmed expression of these CD36 variants on the plasma membrane of HEK293T cells by flow cytometry (Figure 1B). After U937 cells were transfected with CD36 mutant constructs, stably transfected U937 cells showing high level of CD36 expression were selected among the transfected cell lines. U937 mock- and CD36 dominant negative-transfectants were then treated with OxLDL (80 µg/ml) for 8 h. Immunoblot analysis showed that, contrary to what might be expected, Hsp70 expression drastically increased in the cells expressing CD36 variants compared with control U937 mock-transfected cells (Figure 1C). In contrast, no difference was observed between the control and CD36 variant-transfected cells in Hsp70 expression after mild heat shock or treatment with 15d-PGJ2, a factor which induces Hsp70 expression independently of OxLDL (Figure 1D). These results suggest that CD36 signaling inhibits Ox-LDL-mediated Hsp70 expression.

To confirm whether CD36 activation inhibits Hsp70 induction, we transiently transfected U937 cells with siRNAs for the CD36 gene and then treated them with OxLDL. Northern blot analysis revealed a decrease in CD36 mRNA expression in cells transiently transfected with CD36 siRNAs, compared to control cells transfected with mismatched tyrosinase siRNAs (Figure 2A). The effect of CD36 siRNA on CD36 protein expression on the U937 cell surface was confirmed by FACS analysis (data not shown). As shown in Figure 2B, treatment with CD36 siRNA led to increased Hsp70 expression in U937 cells. This finding was supported by the results showing that CD36-downregulated cell lines expressed more Hsp70 proteins than CD36-upregulated cells when they were treated with OxLDL. Consistent with a previous report (Elstner et al., 1998), exposure of human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells, which express CD36 and PPARγ, to troglitazone (10 µM, 4 days) increased expression of CD36 protein about 2-fold when compared to untreated MCF-7 cells; their exposure to all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA; 1 µM, 4 days) alone decreased CD36 expression about 2-fold compared with untreated cells (data not shown). When MCF-7 cells were treated with OxLDL following their exposure to troglitazone, expression of Hsp70 decreased (Figure 2C). In contrast, OxLDL-induced Hsp70 expression increased in MCF-7 cells treated with ATRA. Taken together, these results indicate that OxLDL-induced CD36 signaling down-regulates Hsp70 expression not only in U937 monocytic cells but also in MCF-7 epithelial cells.

The effect of OxLDL on Hsp70 protein expression is dependent on the expression levels of CD36. (A) U937 cells were transiently transfected with CD36 or tyrosinase siRNA as mismatched siRNA. After transfection, the cells were incubated for 24 h in SFM and then analyzed for CD36 mRNA expression by Northern blot (NB) analysis. GAPDH bands were detected as loading controls. The graph represents relative expression levels of CD36, shown as relative band intensity by densitometer measurements. CD36 expression level of controls is designated as 100%. (B) After transfection of siRNAs as in (A), the cells were treated with OxLDL (80 µg/ml) for 8 h, and then induction levels of Hsp70 were determined. β-actin levels were also determined as loading controls. (C) MCF-7 cells were stimulated with troglitazone (10 µM) or ATRA (1 µM) for 4 days prior to OxLDL (80 µg/ml) treatment for 8 h. Expression levels of Hsp70 protein were evaluated by Western blot analysis. Relative expression levels of Hsp70 are shown as previously described.

CD36-mediated inhibition of Hsp70 expression is through activation of PPARγ

The binding of OxLDL to CD36 has been known to activate PPARγ (Nicholson et al., 1995; Tontonoz et al., 1998). To determine if OxLDL inhibits Hsp70 expression through activation of PPARγ, we pre-incubated U937 cells with PGF2γ (0.1 µM) for 1 h prior to OxLDL treatment. PGF2α has been shown to inactivate PPARγ through phosphorylation (Reginato et al., 1998). Immunoblot assays were then used to determine whether PGF2α modulates the activity of OxLDL. Addition of PGF2α diminished the inhibitory effect of CD36 on OxLDL-induced Hsp70 protein expression, but not mRNA expression (Figure 3A and B). PGF2α alone had no effect on Hsp70 protein expression. These results indicate that CD36-mediated inhibition of Hsp70 induction is indeed via PPARγ activation.

The effect of OxLDL on Hsp70 protein expression is dependent on PPARγ. (A) U937 mock-transfectants were pre-incubated in 1 ml of SFM in the absence or presence of PGF2α (0.1 µM) for 1 h, prior to incubation in the absence or presence of OxLDL (80 µg/ml). After 8 h, expression levels of Hsp70 protein were evaluated by Western blot analysis. (B) U937 mock-transfectants were treated as in (A) and then analyzed for Hsp70 mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis. GAPDH bands were detected as loading controls. (C) U937 CD36 ΔN/C transfectants were pre-incubated in 1 ml of SFM in the absence or presence of ciglitazone (5 µM) for 1 h and then treated as in (A). Expression levels of Hsp70 protein were evaluated by Western blot (WB) analysis. (D) After treated as in (C), U937 CD36 ΔN/C transfectants were collected and analyzed for Hsp70 mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis. (E) U937 cells were transiently transfected with PPARγ or CD36 siRNA. After transfection, the cells were incubated for 24 h in SFM and then analyzed for PPARγ mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis. GAPDH bands were detected as loading controls. (F) U937 cells were transiently transfected with either PPARγ or control GAPDH siRNA. After transfection, cells were treated with OxLDL (80 µg/ml) for 8 h. Induction levels of Hsp70 protein were then determined by Western blot analysis, with β-actin levels serving as loading controls. Relative expression levels of Hsp70 are shown as values relative to Hsp70 expression levels of untreated controls (designated as 100%).

We next examined the effect of synthetic PPARγ activators on OxLDL-induced Hsp70 expression in CD36ΔN/C transfectants. Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) such as ciglitazone and troglitazone are known to be PPARγ-selective activators (Consoli and Devangelio, 2005). Ciglitazone alone had no effect on Hsp70 protein expression. However, treatment of CD36ΔN/C transfected cells with both OxLDL and ciglitazone resulted in a dramatic decrease in the expression levels of Hsp70 protein when compared to OxLDL treatment only (Figure 3C). Consistent with the results described above, the activation of PPARγ by ciglitazone also did not appear to inhibit Hsp70 mRNA expression (Figure 3D). Similar results were obtained with troglitazone (data not shown).

To confirm the inhibitory effect of PPARγ activation on Hsp70 induction, we then transiently transfected U937 cells with siRNAs directed against PPARγ. Transfection of U937 cells with siRNAs for PPARγ resulted in a diminished expression of PPARγ mRNA (Figure 3E). Figure 3F reveals that treatment with PPARγ siRNA led to increased Hsp70 protein expression in U937 cells with OxLDL treatment. Taken together, these results suggest that CD36 signaling attenuates Hsp70 expression at the post-transcriptional level through activation of PPARγ.

CD36 signaling downregulates Hsp70 expression through inhibition of translation via PPARγ activation

To further validate that CD36 signaling regulates Hsp70 gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, we then chose to examine whether Hsp70 mRNA expression is drastically altered by the overexpression of CD36 variants compared with control U937 cells when treated with OxLDL. Results showed that there was no difference between control U937 cells and CD36 variant transfectants in the expression levels of Hsp70 mRNA (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 1C, the expression levels of Hsp70 protein were higher in CD36 variant transfectants than in control U937 cells. Thus, CD36 signaling may regulate Hsp70 gene expression at the post-transcriptional level.

Activation of CD36 or PPARγ inhibits hsp70 protein synthesis in U937 cells. (A) U937 mock-transfectants or dominant negative CD36-transfectants were incubated for 8 h in the absence or presence of OxLDL (80 µg/ml). Cells were collected and analyzed for Hsp70 mRNA expression by Northern blot analysis. GAPDH bands were detected as loading controls. (B-D) U937 cells were pre-treated with heat shock for 20 min at 42℃ and then exposed to 5 µg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) (B), 5 µM troglitazone (Trog) (C), or both reagents (D) after 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 h following heat shock treatment. At 8 h, protein lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot (WB) analysis to monitor Hsp70 protein levels. (E) U937 cells were transiently transfected with PPARγ or control GAPDH siRNA. After transfection, cells were subjected to heat shock and then exposed to 5 µM troglitazone for 8 h; protein lysates were prepared and subjected to Western blot analysis to monitor Hsp70 protein levels. βf-actin levels served as loading controls. Relative expression levels of Hsp70 are shown as values relative to Hsp70 expression levels of untreated controls (designated as 100%).

Next, we tested whether PPARγ activation decreases Hsp70 protein stability. We hypothesized that if this were the case, then troglitazone treatment should accelerate Hsp70 elimination under conditions in which translation is blocked by the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide. As shown in Figure 4B and 4C, Hsp70 expression was reduced in the U937 cells treated with cycloheximide or troglitazone after 0-2 h following heat shock. Troglitazone had no discernible effect on the rate or extent of Hsp70 downregulation following the addition of cycloheximide (Figure 4D). As a control, actin protein levels were also examined and no differences were observed (Figure 4B-D). Thus, PPARγ activation does not decrease Hsp70 protein stability in U937 cells, suggesting that it might suppress de novo synthesis of Hsp70 proteins.

Previous reports have shown that troglitazone-mediated suppression of translation is independent of PPARγ activation (Palakurthi et al., 2001; Cho et al., 2006). Since these results were contradictory to ours, we conducted experiments to confirm a direct role for PPARγ in toglitazone-mediated inhibition of Hsp70 protein expression in human monocytes. U937 cells were transiently transfected with siRNAs for PPARγ, or for GAPDH as a control. Transient transfectants were treated with troglitazone for 8 h immediately after heat shock. Figure 4E showed that siRNA inhibition of PPARγ reversed the suppressive effects of troglitazone on Hsp70 protein expression, whereas that of GAPDH did not. These results indicate that troglitazone inhibits Hsp70 protein expression via a PPARγ-dependent mechanism.

Discussion

Several reports have shown that OxLDL induces expression of Hsp70 in human endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (Zhu et al., 1994, 1995, 1996). Our finding described here show that Hsp70 can be induced by OxLDL in monocytes/macrophages as well. OxLDL may cause oxidative damage to the arterial wall and macrophages, leading to the induction of Hsp70 in atherosclerotic plaque. In fact, Hsp70 induction was observed in the necrotic lipid core of advanced lesions in hyperhomocysteinemic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (Zhou et al., 2004) as well as in human and rabbit atherosclerotic lesions (Berberian et al., 1990; Geetanjali et al., 2002). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying OxLDL-mediated Hsp70 induction are unknown.

OxLDL uptake into monocytes/macrophages is mediated by scavenger receptors such as CD36 and SR-A (Nicholson and Hajjar, 2004). CD36 plays a key role in the binding and internalization of OxLDL. In this study, we investigated the role of CD36 and its functional components of the cytoplasmic tail in OxLDL-mediated Hsp70 induction. CD36 contains the N-terminal cytoplasmic tail, which plays a role in targeting the receptor to the plasma membrane (Tao et al., 1996; Gruarin et al., 2000). The C-terminal tail is known to induce intracellular signaling events (Huang et al., 1991; Bull et al., 1994). In the present study, three truncated CD36 constructs, localized in the N- and/or the C-terminal cytoplasmic tails, were produced and stably expressed in U937 cells. These constructs contained an extracellular domain and both N- and C-terminal transmembrane domains; the binding domain of OxLDL is located in the extracellular domain (Puente Navazo et al., 1996; Pearce et al., 1998). A previous study showed the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail was required for the endocytosis of OxLDL (Malaud et al., 2002). These results suggest that overexpression of CD36 variants in monocytes may suppress the function of intact CD36 in a dominant-negative way by inhibiting the OxLDL-mediated CD36 signaling. Hsp70 expression drastically increased in the cells overexpressing CD36 variants compared with control U937 cells when they were treated with OxLDL. This indicates that the binding of OxLDL to CD36 and subsequent internalization may trigger signaling that inhibits Hsp70 induction in monocytes, while OxLDL may induce Hsp70 expression if it binds to membrane components other than CD36. In addition, findings show that both cytoplasmic domains of CD36 may be responsible for the inhibitory function of CD36. Involvement of CD36 in regulation of OxLDL-mediated Hsp70 induction is supported by the CD36-downregulated MCF-7 cell lines that induced more Hsp70 protein than CD36-upregulated ones when they were treated with OxLDL. Thus, these combined studies show, for the first time, that CD36 is involved in regulating Ox-LDL-mediated Hsp70 expression.

Our data demonstrates that PPARγ is involved in the CD36-mediated inhibition of Hsp70 expression. PPARγ is a member of a nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that heterodimerizes with the RXR and up-regulates the transcription of genes involved in adipogenesis and lipid metabolism (Tontonoz et al., 1995). Addition of PGF2α, a PPARγ inactivator, diminished the inhibitory effect of CD36 signaling on OxLDL-induced Hsp70 protein expression in U937 cells. In addition, knockdown of PPARγ by injection of siRNA showed the same effect as the PGF2α treatment. Dramatic decreases in the expression levels of Hsp70 protein were observed in the CD36ΔN/C transfectants treated with both OxLDL and ciglitazone, a synthetic PPARγ activator, when compared with the group treated with OxLDL only, reflecting the inhibitory effect of ciglitazone. Therefore, the conclusion can be reached that PPARγ mediates the CD36 inhibitory signaling of Hsp70 induction, which is triggered by OxLDL binding.

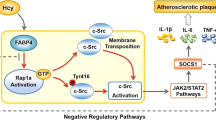

Additionally, we show here that PPARγ ligands suppress the expression of stress-induced pro-inflammatory genes such as Hsp70 at the translational level. Previous studies showed that treatment of cells with PPARγ activators such as TZDs and PGJ2 inhibited translation by phosphorylating the eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF-2α) subunit (Palakurthi et al., 2001; Cho et al., 2006). These inhibitory effects appear to be independent of PPARγ activation. However, our data demonstrate that specific inhibition of PPARγ activity by siRNA transfection or PGF2α treatment leads to an increase in OxLDL-induced Hsp70 protein expression. Also, siRNA inhibition of PPARγ reversed the troglitazone-mediated inhibition of Hsp70 protein expression. Collectively, these results suggest that OxLDL and TZDs may inhibit translation by PPARγ-dependent as well as PPARγ-independent mechanisms in monocytes/macrophages. Recent studies suggest that PPARγ can suppress the function of other transcription factors, such as the nuclear receptor co-repressor (NCoR)-histone deacetylase-3 (HDAC3) complexes, by direct interaction (Pascual et al., 2005). Therefore, it is possible that PPARγ activation leads to the suppression of translation by binding to translation machinery proteins under oxidative stress conditions as well. It remains to be elucidated whether PPARγ regulates translation through a direct interaction with translation factors, and, if so, which factors. Thus, molecular mechanisms underlying anti-inflammatory properties of PPARγ may include not only transrepression of NF-κB-mediated transcription but also suppression of de novo synthesis of stress-induced pro-inflammatory proteins.

In summary, we demonstrate here that the binding of OxLDL to CD36 inhibits Hsp70 expression in monocytes through a PPARγ-dependent pathway. Moreover, our findings provide the first evidence that CD36 and PPARγ signaling regulates oxidative stress-induced Hsp70 expression at the translational level. These findings reveal a molecular basis for control of OxLDL-induced inflammation by CD36 and PPARγ, thereby suggesting a new approach in the pursuit of treatment for inflammatory reactions found in atherosclerosis.

Abbreviations

- ATRA:

-

all-trans-retinoic acid

- eIF-2α:

-

eukaryotic initiation factor-2α

- HDAC3:

-

histone deacetylase-3

- Hsp:

-

heat shock protein

- NCoR:

-

nuclear receptor co-repressor

- OxLDL:

-

oxidized low density lipoprotein

- RXR:

-

retinoid X receptor

- TSP:

-

thrombospondin

- TZD:

-

thiazolidinediones

References

Berberian PA, Myers W, Tytell M, Challa V, Bond MG . Immunohistochemical localization of heat shock protein-70 in normal-appearing and atherosclerotic specimens of human arteries . Am J Pathol 1990 ; 136 : 71 - 80

Bull HA, Brickell PM, Dowd PM . Src-related protein tyrosine kinases are physically associated with the surface antigen CD36 in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells . FEBS Lett 1994 ; 351 : 41 - 44

Calvo D, Gomez-Coronado D, Suarez Y, Lasuncion MA, Vega MA . Human CD36 is a high affinity receptor for the native lipoproteins HDL, LDL, and VLDL . J Lipid Res 1998 ; 39 : 777 - 788

Cho DH, Choi YJ, Jo SA, Ryou J, Kim JY, Chung J, Jo I . Troglitazone acutely inhibits protein synthesis in endothelial cells via a novel mechanism involving protein phosphatase 2A-dependent p70 S6 kinase inhibition . Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006 ; 291 : C317 - C326

Choi G, Lee SK, Jung KC, Choi EY . Detection of homodimer formation of CD99 through extracelluar domain using bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis . Exp Mol Med 2007 ; 36 : 746 - 755

Consoli A, Devangelio E . Thiazolidinediones and inflammation . Lupus 2005 ; 14 : 794 - 797

Elstner E, Muller C, Koshizuka K, Williamson EA, Park D, Asou H, Shintaku P, Said JW, Heber D, Koeffler HP . Ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorgamma and retinoic acid receptor inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of human breast cancer cells in vitro and in BNX mice . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998 ; 95 : 8806 - 8811

Febbraio M, Hajjar DP, Silverstein RL . CD36: a class B scavenger receptor involved in angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and lipid metabolism . J Clin Invest 2001 ; 108 : 785 - 791

Geetanjali B, Uma S, Bansal MP . Changes in heat shock protein 70 localization and its content in rabbit aorta at various stages of experimental atherosclerosis . Cardiovasc Pathol 2002 ; 11 : 97 - 103

Gruarin P, Thorne RF, Dorahy DJ, Burns GF, Sitia R, Alessio M . CD36 is a ditopic glycoprotein with the N-terminal domain implicated in intracellular transport . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000 ; 275 : 446 - 454

Han Z, Truong QA, Park S, Breslow JL . Two Hsp70 family members expressed in atherosclerotic lesions . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003 ; 100 : 1256 - 1261

Huang MM, Bolen JB, Barnwell JW, Shattil SJ, Brugge JS . Membrane glycoprotein IV (CD36) is physically associated with the Fyn, Lyn, and Yes protein-tyrosine kinases in human platelets . Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991 ; 88 : 7844 - 7848

Jiang C, Ting AT, Seed B . PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines . Nature 1998 ; 391 : 82 - 86

Kanwar RK, Kanwar JR, Wang D, Ormrod DJ, Krissansen GW . Temporal expression of heat shock proteins 60 and 70 at lesion-prone sites during atherogenesis in ApoE-deficient mice . Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001 ; 21 : 1991 - 1997

Lee KJ, Kim HA, Kim PH, Lee HS, Ma KR, Park JH, Kim DJ, Hahn JH . Ox-LDL suppresses PMA-induced MMP-9 expression and activity through CD36-mediated activation of PPAR-g . Exp Mol Med 2004 ; 36 : 534 - 544

Lee KJ, Kim YM, Kim DY, Jeoung D, Han K, Lee ST, Lee YS, Park KH, Park JH, Kim DJ, Hahn JH . Release of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and the effects of extracellular Hsp70 on matric metalloproteinase-9 expression in human monocytic U937 cells . Exp Mol Med 2006 ; 38 : 364 - 374

Li WX, Howard RJ, Leung LL . Identification of SVTCG in thrombospondin as the conformation-dependent, high affinity binding site for its receptor, CD36 . J Biol Chem 1993 ; 268 : 16179 - 16184

Malaud E, Hourton D, Giroux LM, Ninio E, Buckland R, McGregor JL . The terminal six amino-acids of the carboxy cytoplasmic tail of CD36 contain a functional domain implicated in the binding and capture of oxidized low-density lipoprotein . Biochem J 2002 ; 364 : 507 - 515

Metzler B, Abia R, Ahmad M, Wernig F, Pachinger O, Hu Y, Xu Q . Activation of heat shock transcription factor 1 in atherosclerosis . Am J Pathol 2003 ; 162 : 1669 - 1676

Nicholson AC, Frieda S, Pearce A, Silverstein RL . Oxidized LDL binds to CD36 on human monocyte-derived macrophages and transfected cell lines. Evidence implicating the lipid moiety of the lipoprotein as the binding site . Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1995 ; 15 : 269 - 275

Nicholson AC, Hajjar DP . CD36, oxidized LDL and PPAR gamma: pathological interactions in macrophages and atherosclerosis . Vascul Pharmacol 2004 ; 41 : 139 - 146

Ogawa S, Lozach J, Benner C, Pascual G, Tangirala RK, Westin S, Hoffmann A, Subramaniam S, David M, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK . Molecular determinants of crosstalk between nuclear receptors and toll-like receptors . Cell 2005 ; 122 : 707 - 721

Palakurthi SS, Aktas H, Grubissich LM, Mortensen RM, Halperin JA . Anticancer effects ofthiazolidinediones are independent of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and mediated by inhibition of translation initiation . Cancer Res 2001 ; 61 : 6213 - 6218

Park HK, Park EC, Bae SW, Park MY, Kim SW, Yoo HS, Tudev M, Ko YH, Choi YH, Kim S, Kim DI, Kim YW, Lee BB, Yoon JB, Park JE . Expression of heat shock protein 27 in human atherosclerotic plaques and increased plasma level of heat shock protein 27 in patients with acute coronary syndrome . Circulation 2006 ; 114 : 886 - 893

Pascual G, Fong AL, Ogawa S, Gamliel A, Li AC, Perissi V, Rose DW, Willson TM, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK . A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-gamma . Nature 2005 ; 437 : 759 - 763

Pearce SF, Roy P, Nicholson AC, Hajjar DP, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL . Recombinant glutathione S-transferase/CD36 fusion proteins define an oxidized low density lipoprotein-binding domain . J Biol Chem 1998 ; 273 : 34875 - 34881

Puente Navazo MD, Daviet L, Ninio E, McGregor JL . Identification on human CD36 of a domain (155-183) implicated in binding oxidized low-density lipoproteins (Ox-LDL) . Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996 ; 16 : 1033 - 1039

Reginato MJ, Krakow SL, Bailey ST, Lazar MA . Prostaglandins promote and block adipogenesis through opposing effects on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma . J Biol Chem 1998 ; 273 : 1855 - 1858

Roma P, Catapano AL . Stress proteins and atherosclerosis . Atherosclerosis 1996 ; 127 : 147 - 154

Stewart BW, Nagarajan S . Recombinant CD36 inhibits oxLDL-induced ICAM-1-dependent monocyte adhesion . Mol Immunol 2006 ; 43 : 255 - 267

Svensson PA, Asea A, Englund MC, Bausero MA, Jernas M, Wiklund O, Ohlsson BG, Carlsson LM, Carlsson B . Major role of HSP70 as a paracrine inducer of cytokine production in human oxidized LDL treated macrophages . Atherosclerosis 2006 ; 185 : 32 - 38

Tao N, Wagner SJ, Lublin DM . CD36 is palmitoylated on both N- and C-terminal cytoplasmic tails . J Biol Chem 1996 ; 271 : 22315 - 22320

Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM . Regulation of adipocyte gene expression and differentiation by peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma . Curr Opin Genet Dev 1995 ; 5 : 571 - 576

Tontonoz P, Nagy L, Alvarez JG, Thomazy VA, Evans RM . PPARgamma promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL . Cell 1998 ; 93 : 241 - 252

Zhou J, Werstuck GH, Lhotak S, de Koning AB, Sood SK, Hossain GS, Moller J, Ritskes-Hoitinga M, Falk E, Dayal S, Lentz SR, Austin RC . Association of multiple cellular stress pathways with accelerated atherosclerosis in hyperhomocysteinemic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice . Circulation 2004 ; 110 : 207 - 213

Zhu W, Roma P, Pellegatta F, Catapano AL . Oxidized-LDL induce the expression of heat shock protein 70 in human endothelial cells . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994 ; 200 : 389 - 394

Zhu W, Roma P, Pirillo A, Pellegatta F, Catapano AL . Human endothelial cells exposed to oxidized LDL express hsp70 only when proliferating . Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996 ; 16 : 1104 - 1111

Zhu WM, Roma P, Pirillo A, Pellegatta F, Catapano AL . Oxidized LDL induce hsp70 expression in human smooth muscle cells . FEBS Lett 1995 ; 372 : 1 - 5

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. B. Seed for providing valuable CD36 cDNA plasmid. This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (No. R11-2001-090-02005-0) (to J-H.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, KJ., Ha, ES., Kim, MK. et al. CD36 signaling inhibits the translation of heat shock protein 70 induced by oxidized low density lipoprotein through activation of peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ. Exp Mol Med 40, 658–668 (2008). https://doi.org/10.3858/emm.2008.40.6.658

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3858/emm.2008.40.6.658