Abstract

Genetic counselling for presymptomatic testing is complex, bringing both ethical and practical questions. There are protocols for counselling but a scarcity of literature regarding quality assessment of such counselling practice. Generic quality assessment tools for genetic services are not specific to presymptomatic testing (PST). Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify aspects of effective counselling practice in PST for late-onset neurological disorders. We used the Delphi method to ascertain the views of relevant European experts in genetic counselling practice, ascertained via published literature and nomination by practitioners. Ethical approval was obtained. Questionnaires were sent electronically to a list of 45 experts, (Medical Doctors, Geneticists, Genetic Counsellors and Genetic Nurses), who each contributed to one to three rounds. In the first round, we provided a list of relevant indicators of quality of practice from a literature review. Experts were requested to evaluate topics in four domains: (a) professional standards; (b) service standards; (c) the consultant’s perspective; and (d) protocol standards. We then removed items receiving less than 65% approval and added new issues suggested by experts. The second round was performed for the refinement of issues and the last round was aimed at achieving final consensus on high-standard indicators of quality, for inclusion in the assessment tool. The most relevant indicators were related to (1) consultant-centred practice and (2) advanced counselling and interpersonal skills of professionals. Defined high-standard indicators can be used for the development of a new tool for quality assessment of PST counselling practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic counselling for presymptomatic testing (PST) for late-onset disorders is complex in view of the multiple ethical and practical questions connected with such testing.1, 2, 3 PST has gradually become more available to patients due to enhanced knowledge of the genetic cause of disease and available technologies.4 Protocols for genetic counselling are well defined; however, there is a scarcity of literature regarding quality assessment of such counselling practice.4, 5 Moreover, generic quality assessment tools developed for genetic services might be not appropriate for the PST context.6 Where research exists, the assessment of genetic counselling quality for PST has been mainly focussed on the psychological impact or uptake of testing.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

With this gap in the evidence base, we investigated consultants’ views of effective counselling practice in the context of PST.13 We interviewed 22 consultants undergoing PST for late-onset neurological disorders (Huntington disease, spinocerebellar ataxias and familial amyloid polyneuropathy ATTRV30M) in the three major counselling services for these diseases in Portugal; our results showed the importance of adjustment of the protocol on a ‘case-by-case’ basis and the role of engagement and counselling skills of the counsellor during the decision-making process. Consultants in that study described PST consultations as more personalised than those they had experienced in other health-care settings.

Building on that work, we decided to explore professionals’ views of relevant quality indicators of their own genetic counselling practice, and we interviewed 85% of the Portuguese genetic health professionals currently involved in delivering services in this context.14 Between June and December 2012 we undertook semistructured in-person interviews at the four public institutions where genetic counselling for PST is currently offered in Portugal (three genetics departments from general hospitals and one genetics centre). We found that, although core components of genetic counselling were well known, the notion of quality indicators was not familiar to these professionals, nor were the instruments to assess it. Professionals also discussed some specific challenges of PST in genetic counselling practice, such as the ambiguity of the health/illness status and the need to promote the consultants’ autonomy during the process.14 Integration of genetic counsellors into genetic services was emphasised, as well as the need to continue genetic counselling training options. The first generation of Portuguese Genetic Counsellors started a formal training at the master level in 2009.15 At the present time, less than half of graduated genetic counsellors are full-time involved in genetic counselling provision as there is no national professional recognition for practice yet.15

The work described above indicated that a quality assessment tool for PST was required. We decided to obtain the opinions of European experts in the field to build upon our national studies to further the development of a quality-assessment tool and support practice recommendations. Therefore, the aim of this study was to identify quality aspects of effective counselling practice in presymptomatic testing for late-onset neurological disorders.

Materials and Methods

Design

The Delphi approach has been identified as a useful methodology to establish (as objectively as possible) a consensus on a complex problem in circumstances where accurate information does not exist.16 We used the Delphi method to ascertain the views of a range of experts in the field of presymptomatic testing. The Delphi method has been widely used in health-care research and has recently been used effectively in the area of genetic health services.3 The rationale for choosing the Delphi approach to obtain group consensus for the identification, prioritisation of development of concepts related to a particular issue is well documented.16 A common characteristic in descriptions of the method is the structuring of a communication process with a group of experts, where some feedback of individual contributions of information and knowledge is provided during successive rounds of data collection. Whereas the overall judgement of the group is important, the concept of consensus is also an essential component of the method and there is an opportunity for individuals to revise their views while remaining anonymous.16, 17

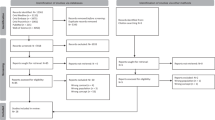

Participants

Choosing an appropriate panel of experts is one of the key aspects of the Delphi method. We aimed to recruit a total of 45 experts to the study. We followed a rigorous procedure to select experts for our study to ensure the identification of relevant professionals. The identification of experts was made through a literature review and contacts with specialized centres and relevant organisations. As a result of the initial selection of potential participants we prepared a preliminary list of experts and contacted them for the nomination of three other experts. More information on the selection procedure is included in the Supplementary Material.

Using a participant information sheet we invited 45 experts. The information provided to potential participants included the length of the initial questionnaire, approximate time commitment, number of expected rounds and anonymous feedback within the group of experts. All participants gave consent to be involved in the study.

Data collection and analysis method

The survey created for the first round was prepared by the authors using an extensive review of literature on the field we already published6 and relevant quality indicators of genetic counselling practice at PST that we recently assessed on consultants’ views.13 The questionnaire was placed online using Survey Monkey (a survey software, Palo Alto, CA, USA). A link to the created questionnaire in each round was sent by e-mail to all panellists. In addition, two reminders were sent at each round aiming at the collection of as much data as possible.

The survey created for the first round was prepared using an extensive review of literature on the field we already published6 and relevant quality indicators of genetic counselling for PST, including recent work based on consultants’ views.13 Experts were asked to score each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale, where 1 was least relevant and 5 was most relevant. There were 49 topics in four domains: professional (10 issues), services (11 issues), protocol standards (15 issues) and consultant-centred practice (13 issues; Supplementary Document).

The questionnaire was sent initially to five senior and experienced professionals, two medical geneticists from Portugal and Canada and three genetic counsellors from Portugal, United Kingdom and Cuba. They were not invited as participants on the present study and were selected based on their proved expertise as researchers and previous collaborative projects with the authors.

The suitability of a variety of statistical analyses to interpret the data on Delphi studies has been stated.17 We use descriptive statistics (percentages) for analysis of quantitative data and content analysis for qualitative data collected through responses to open questions.

Results

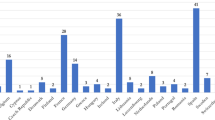

The sociodemographic profile of the group is presented in Table 1. Experts from 11 countries were mainly medical doctors working at Hospitals, with a mean of almost 20 years of clinical experience and 15 years in counselling research (Table 1). As participants were anonymous, we were not able to identify those involved: there were 60 participations: 29 (64.4%) in Round 1; 14 (31.1%) in Round 2 and 17 (37.7%) in Round 3.

After Round 1 we retained all items that were assigned a score of either 4 or 5 by 65% or more respondents; five items were excluded, four items were reformulated and seven new items were suggested by experts. A second list of items was sent to experts with a new ranking scale (slightly, moderately or extremely relevant; Supplementary Document).

After the second round, we found that the lowest ranked issues were related to PST protocol standards. Conversely, the highest ranked issues concerned consultant-centred practice of genetic counselling and professionals’ counselling skills.

In the next phase, we excluded another seven items that scored less than 2.5 (3.0 being the higher mean value). We also short-listed 20 items that the experts assessed as the most relevant indicators of quality (ranked above 2.8) and 25 items that were scored in the intermediate range (2.5–2.8).

In the third round, a slight majority of experts (53.8%) agreed to keep only those issues in high scoring bracket, 7.7% voted keeping all issues from the previous round, whereas 38.5% of the experts chose to retain some in the intermediate range. From this intermediate list, we decided then to retain only those items that reached 80% of agreement. Finally, 25 items were considered as high-standard quality indicators (Table 2).

Regarding the current assessment of the genetic counselling practice, the majority of experts were not aware of any specific tool to assess quality in the context of PST for LONDs. Only two tools (generic to clinical genetics services) were mentioned: the Eurogentest tool18 and the Genetic Counselling Outcome Scale.19 Furthermore, we also found that current procedures for the quality assessment of genetic counselling practice are based on local quality questionnaires answered by consultands, clinical discussion of cases, clinical supervision, yearly reflection by the multidisciplinary team and report to the heads of departments, among other strategies.

Discussion

In terms of the strength of our study, an expert group of professionals with extensive experience in genetic counselling in both clinical and research settings is an appropriate cohort in terms of their skills and knowledge of the topic. There are several incentives that may lead the experts to participate in a Delphi study: being nominated among a selected group, the opportunity to learn from the consensus building, increasing their visibility, could be motivational aspects that also encourage busy experts.20 Nevertheless, it was difficult to obtain responses throughout the three rounds and reminders were sent in order to increase expert participation. Unequal participation on each round can be explained by the different time frames for completing each round, but also as it is a sequential process some experts might have felt that it increases the workload and the amount of time needed to successfully complete the study. These have been described as weaknesses of the Delphi technique17 that may explain the possibility of low response rate along the whole study.

Whereas a consensus about the components of genetic counselling seems unproblematic, trying to define what is effective genetic counselling practice is still a challenge.21, 22 Previous studies on quality of genetic counselling have been mainly focused on outcomes and have been frequently related to changes in reproductive behaviour and/or client knowledge among other factors, although we believe that effectiveness in genetic counselling remains fundamentally related to its process. A review by Pilnick et al. 23 highlighted the gap in our knowledge of the relationship between outcome and process, emphasising the need to identify specific components of the process that results in the consultant’s satisfaction and the factors that are likely to influence it.23 In addition, we consider that quality assessment can only be achieved effectively through the use of appropriate methodological tools. If genetic counselling is a communication process, it can only be fully understood when studied as such.23 Nevertheless, even when results of our study showed that experts highlighted the consultant-centred practice as a high standard of quality during PST counselling, tools that are currently being used did not specifically address the process of genetic counselling.

The high-standard list of quality indicators that were defined as a result from our study can be used as a survey tool for genetic services to assess their own practice. This initial list is a starting point while further indicator development is needed to provide a more comprehensive picture of care delivery.24 Nevertheless, we believe that service delivery is different within 11 countries represented by participant experts and much can be already learned to aid in providing quality service.

Guidelines vs protocols

Predictive testing has been carried out according to protocols, as many clinical procedures are, and these have been much standardised for the purposes of research.25, 26 There is a difference between protocols and guidelines,27 and this distinction might be relevant while trying to define indicators of an effective practice of genetic counselling and ways to assess it. In accordance with Tibben and van Oostrom (2004), we support the idea that guidelines are ought not to be used inflexibly, but as a framework of recommended procedures for careful testing.28 Following the guidelines may also provide a safety net that comforts the test candidate and his or her companion. In accordance, an expert group3 has already focused on the principles and goals of PST by developing a coherent guideline that, rather than making specific prescriptions in terms of numbers of sessions of counselling, enables practitioners to use their own professional judgment to individualise the counselling process. Protocols are not intended to be used as a ‘straight jacket’; however, we think that the case-by-case adjustment is still poorly documented.29, 30

As the experts of our study emphasised, we believe that it is crucial that all genetic health professionals (genetic counsellors, medical geneticists, genetic nurses and other specialists) are well armed with a set of personal and professional competences and skills that will allow them to conduct the counselling process safely and effectively. Our study participants valued the open attitude of counsellors and their capability to explore doubts and emotions, in line with basic models of the counselling relationship, as defined by Rogers.31 Lack of counselling skills is a barrier to an effective interaction.32 This is particularly relevant in presymptomatic testing, where a considerable amount of time is given for reflection about the willingness to be tested, the individual’s readiness and their appreciation of the potential consequences. The appropriate use of counselling skills requires expertise and continuous training.33, 34 Defining the qualities needed to become an effective genetic counsellor remains a matter of discussion, but as a first step educational standards have been defined;35 some European countries already have implemented counselling supervision systems.36 The registration system for the genetic counsellors and genetic nurses (www.eshg.org) can be seen as an important factor in quality improvement of genetic counselling practice in Europe.37

Conclusion

As a result from our study, high-standard quality indicators were defined and can be used as a survey tool for genetic services to assess their own practice. Mainly, effectiveness of genetic counselling practice seems to be related to professional skills and consultant-centred practice. For that reason, we believe that it is of extreme importance for quality assurance that genetic counsellors pay attention to their own personal and professional skills, while counselling training opportunities need to be offered. Systematic counselling and clinical supervision are also crucial to achieve this and, as a result, to improve the quality of practice. Furthermore, process studies are needed in order to look at genetic counselling as a truly communicative process.

References

Evers-Kiebooms G, Welkenhysen M, Claes E, Decruyenaere M, Denayer L : The psychological complexity of predictive testing for late onset neurogenetic diseases and hereditary cancers. Soc Sci Med 2000; 51: 831–841.

Evers-Kiebooms G : Genetic counselling for late-onset disorders; in Kristoffersson U, Schmidtke J, Cassiman JJ (eds): Quality Issues in Clinical Genetic Services. Berlin: Springer, 2010, pp 353–360.

Skirton H, Goldsmith L, Jackson L, Tibben A : Quality in genetic counselling for presymptomatic testing - clinical guidelines for practice across the range of genetic conditions. Eur J Hum Genet 2012; 21: 256–260.

MacLeod R, Tibben A, Frontali M et al: Recommendations for the predictive genetic test in Huntington's disease. Recommendations for the predictive genetic test in Huntington’s disease. Clin Genet 2013; 83: 221–231.

Brain K, Soldan J, Sampson J, Gray J : Genetic counselling protocols for hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer: a survey of UK regional genetics centres. Clin Genet 2003; 63: 198–204.

Paneque M, Sequeiros J, Skirton H : Quality assessment of genetic counselling process in the context of presymptomatic testing for late-onset disorders: a thematic analysis of three review articles. Genet Test Mol Bioma 2012; 16: 36–45.

Duisterhof M, Trijsburg RW, Niermeijer MF, Roos RA, Tibben A : Psychological studies in Huntington’s disease: making up the balance. J Med Genet 2001; 38: 852–856.

Bernhardt C, Schwan AM, Kraus P, Epplen JT, Kunstmann E : Decreasing uptake of predictive testing for Huntington’s disease in a German centre: 12 years’ experience (1993–2004). Eur J Hum Genet 2009; 17: 295–300.

Dufrasne S, Roy M, Galvez M, Rosenblatt D : Experience over fifteen years with a protocol for predictive testing for Huntington disease. Mol Genet Metab 2011; 102: 494–504.

Rodrigues CS, de Oliveira VZ, Camargo G et al: Presymptomatic testing for neurogenetic diseases in Brazil: assessing who seeks and who follows through with testing. J Genet Couns 2012; 21: 101–112.

Schuler-Faccini L, Osorio CM, Romariz F, Paneque M, Sequeiros J, Jardim L : Genetic counseling and presymptomatic testing programs for Machado-Joseph Disease: lessons from Brazil and Portugal. Genet Mol Biol 2014; 37: 263–270.

Cruz-Mariño T, Velázquez-Pérez L, González-Zaldivar Y et al: The cuban program for predictive testing of SCA2: 11 years and 768 individuals to learn from. Clin Genet 2013; 83: 518–524.

Guimarães L, Sequeiros J, Skirton H, Paneque M : What counts as successful in genetic counseling for presymptomatic testing in late-onset disorders? The consultands perspective. J Genet Couns 2013; 22: 437–447.

Mendes A, Guimarães L, Sequeiros J, Skirton H, Paneque M : Professional's views on quality issues of genetic counseling offered for presymptomatic testing for late-onset neurodegenerative disorders: what is relevant? Eur J Hum Genet 2013; 21: 422.

Paneque M, Sequeiros J : The practice of Genetic Counselling in Portugal: where are we and what are the challenges? National Meeting of Portuguesse Society of Human Genetics SPGH, November 2013.

Underhill N : The Deplhi technique. http://www.britishcouncil.org/eltons-delphi_technique.pdf, 2004, accessed on September 2012.

Hsu CH, Sandford B : The Delphi Technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval 2007; 12: Available online http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=12&n=10.

Clarke A, Evers-Kiebooms G, Faucett A et al: Instrument for internal assessment of the quality of genetic counselling within a genetic counselling clinic. http://www.eurogentest.org/professionals/db/news/499/index.xhtml, 2008, accessed 18 July 2014.

McAllister M, Wood AM, Dunn G, Shiloh S, Todd C : The Genetic Counseling Outcome Scale: a new patient-reported outcome measure for clinical genetics services. Clin Genet 2011; 79: 413–424.

Okoli CH, Pawlowski SD : The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management 2004; 42: 15–29.

Kääriäinen H, Hietala M, Kristoffersson U et al: Recommendations for genetic counselling related to genetic testing. Available at http://www.eurogentest.org/fileadmin/templates/eugt/pdf/guidelines_of_GC_final.pdf, 2008, accessed on 18 July 2014.

Rantanen E, Hietala M, Kristoffersson U et al: What is ideal genetic counseling? A survey of current international guidelines. Eur J Hum Genet 2008; 16: 445–452.

Pilnick A : ‘There are no rights and wrongs in these situations’: identifying interactional difficulties in genetic counselling. Sociol Health Ill 2002; 24: 66–88.

Zellerino BC, Milligan SA, Gray JR, Williams MS, Brooks R : Identification and prioritization of quality indicators in clinical genetics: an international survey. Am J Med Genet 2009; 151: 179–190.

IHA/WFN, International Huntington Association and the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Huntington's Chorea: Guidelines for the molecular genetics predictive test in Huntington's disease. J Med Genet 1994; 31: 555–559.

Sequeiros J : O teste preditivo da doença de Machado-Joseph (Predictive Testing for Machado Joseph’s Disease). Porto: UnIGENe-IBMC, 1996.

Jones ME, MacLeod R : Patient views on the delivery of predictive test counselling services for Huntington’s Disease. Eur J Hum Genet 2014; 22: 358.

Sijmons RH, Scott RJ, Lubinski J : Presymptomatic DNA Testing in BRCA1/2: Invited reactions from the field on the van Oostrom and Tibben paper. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2004; 2: 107–109.

Hawkins A, Ho A, Hayden M : Lessons from predictive testing for Huntington disease: 25 years on. J Med Genet 2011; 48: 649–650.

Tibben A : Predictive testing for Huntington’s disease. Brain Res Bull 2007; 72: 165–171.

Mearns D, Thorne B : Person-Centred Counselling in Action. 2nd edn. London: Sage, 1999.

Faulkner A : Breaking Bad News In Effective Interaction with Patients. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1997, pp 119–134.

Skirton H, Voelckel M.A, Patch C : Using a community of practice to develop standards of practice and education for genetic counselors in Europe. J Community Genet 2010; 1: 169–173.

Cordier C, Lambert D, Voelckel MA, Hosterey-Ugander U, Skirton H : A profile of the genetic counsellor and genetic nurse profession in European countries. J Community Genet 2012; 3: 19–24.

Skirton H, Lewis C, Kent A, Coviello D : The members of Eurogentest Unit 6 and ESHG Education Committee. Genetic education and the challenge of genomic medicine: development of core competences to support preparation of health professionals in Europe. Eur J Hum Genet 2010; 18: 972–977.

Clarke A, Middleton A, Cowley L et al: Report from the UK and Eire Association of Genetic Nurses and Counsellors (AGNC) Supervision Working Group on Genetic Counselling Supervision. J Genet Couns 2007; 16: 127–142.

European Registration Process for genetic counsellors and genetic nurses. https://www.eshg.org/471.0.html, accessed on September 2014.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all professionals for their time and precious contribute to this study. MP (SFRH/BPD/66484/2009) has a postdoctoral fellowship from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paneque, M., Sequeiros, J. & Skirton, H. Quality issues concerning genetic counselling for presymptomatic testing: a European Delphi study. Eur J Hum Genet 23, 1468–1472 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.23

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.23

This article is cited by

-

Genetic counseling and testing practices for late-onset neurodegenerative disease: a systematic review

Journal of Neurology (2022)

-

Primary care providers’ lived experiences of genetics in practice

Journal of Community Genetics (2019)

-

The need to develop an evidence base for genetic counselling in Europe

European Journal of Human Genetics (2016)