Abstract

Joubert syndrome and related disorders (JSRD) are clinically and genetically heterogeneous ciliopathies sharing a peculiar midbrain–hindbrain malformation known as the ‘molar tooth sign’. To date, 19 causative genes have been identified, all coding for proteins of the primary cilium. There is clinical and genetic overlap with other ciliopathies, in particular with Meckel syndrome (MKS), that is allelic to JSRD at nine distinct loci. We previously identified the INPP5E gene as causative of JSRD in seven families linked to the JBTS1 locus, yet the phenotypic spectrum and prevalence of INPP5E mutations in JSRD and MKS remain largely unknown. To address this issue, we performed INPP5E mutation analysis in 483 probands, including 408 JSRD patients representative of all clinical subgroups and 75 MKS fetuses. We identified 12 different mutations in 17 probands from 11 JSRD families, with an overall 2.7% mutation frequency among JSRD. The most common clinical presentation among mutated families (7/11, 64%) was Joubert syndrome with ocular involvement (either progressive retinopathy and/or colobomas), while the remaining cases had pure JS. Kidney, liver and skeletal involvement were not observed. None of the MKS fetuses carried INPP5E mutations, indicating that the two ciliopathies are not allelic at this locus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Joubert syndrome and related disorders (JSRD; MIM213300) are clinically and genetically heterogeneous conditions characterized by cerebellar vermis hypo-dysplasia and a peculiar midbrain–hindbrain malformation, the ‘molar tooth sign’ (MTS). The typical neurological features of hypotonia, ataxia, psychomotor delay, oculomotor apraxia and neonatal breathing dysregulation are variably associated with a broad spectrum of multiorgan abnormalities, mainly involving the eyes, kidneys and liver.1 To date, up to 19 genes have been identified with either autosomal recessive (INPP5E, TMEM216, AHI1, NPHP1, CEP290, TMEM67, RPGRIP1L, ARL13B, CC2D2A, TTC21B, KIF7, TCTN1, TCTN2, TMEM237, CEP41, TMEM138, C5orf42, TMEM231) or X-linked inheritance (OFD1).2, 3 Intriguingly, all JSRD genes code for proteins of the primary cilium, making these disorders part of the expanding group of ciliopathies.4 There is large clinical and genetic overlap between JSRD and other ciliopathies such as Meckel syndrome (MKS; MIM249000), isolated nephronophthisis (NPH; MIM256100) and Senior-Loken syndrome (MIM266900). In particular, JSRD and MKS are known to be allelic at nine loci, suggesting that MKS represents the most severe end of the JSRD clinical spectrum.2 It is estimated that known genes overall account for about half of cases, suggesting further genetic heterogeneity; moreover, genotype–phenotype correlates have been clearly established only for few JSRD-causative genes.5, 6, 7, 8, 9

In 2009, Jacoby et al10 identified INPP5E mutations in a family with MORM syndrome, a rare autosomal recessive condition related to Bardet–Biedl syndrome. In the same year, we identified homozygous INPP5E mutations in seven consanguineous families genetically linked to the first JSRD locus (JBTS1) on 9q34.11 To better define the phenotypic spectrum associated with INPP5E mutations and to evaluate their potential contribution to MKS, here we performed a comprehensive molecular screening of this gene in nearly 500 probands diagnosed with either JSRD or MKS.

Patients and methods

Patients

Mutation analysis was performed in a total of 483 probands from two cohorts. The first cohort consisted of 408 probands representative of the whole JSRD clinical spectrum, selected from databases located at the IRCCS CSS-Mendel Institute (Rome, Italy), the University of California San Diego (CA, USA) and the Necker Hospital (Paris, France). All patients had neuroradiologically proven MTS. For each patient, a detailed clinical questionnaire filled by the referring clinician allowed to obtain information on the extent of multiorgan involvement. In particular, nearly all patients underwent measurement of renal and hepatic function, abdominal ultrasound, assessment of visual ability and fundoscopy.

The second cohort included 75 fetuses diagnosed with MKS according on established criteria,12 selected from databases located at the Necker Hospital and the St James’s University Hospital (Leeds, UK). Most patients included in this study had undergone mutation analysis of some JSRD/MKS genes as part of published screenings or in subsequent research studies; probands known to carry mutations in other genes were excluded from the screening. In proband COR28, harboring only a single heterozygous INPP5E variant, mutations in, the TMEM216, AHI1, NPHP1, CEP290, TMEM67, RPGRIP1L and TMEM138 genes have been previously excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all families, and the study was approved by the local ethics committees.

Molecular analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes or frozen tissue, following standard methods. The whole INPP5E (GenBank NM_019892) coding region and splice sites were searched for mutations adopting two distinct strategies. In 308 JSRD probands and in the 75 MKS fetuses, bidirectional sequencing was performed using the BigDye terminator chemistry and an ABI PRISM 3130Xl automated sequencer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). One-hundred JSRD probands underwent whole-exome sequencing (WES) using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exome 50 Mb kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). In patient COR28, in whom only a single heterozygous mutation could be detected, genomic quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) of all exons was performed to search for deletions or duplications, as described.13 Primers and PCR conditions are available upon request.

Bioinformatic analysis

For WES, the GATK software was used for variant identification.14 Thirteen mutation description was checked using the Mutalyzer software (http://www.humgen.nl/mutalyzer/1.0.1); for missense mutations, prediction of pathogenicity was assessed using the PolyPhen-2 software (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/). Multiple sequence alignments of the human INPP5E protein and its orthologues were generated using ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/). Public databases were accessed using the following links: dbSNP Build 132 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/), 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org/), and Exome Sequencing Project’s Exome Variant Server (EVS) (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/).

Results

The INPP5E mutational spectrum

Among JSRD, we identified 12 different INPP5E mutations in 17 patients from 11 families, with an overall prevalence of 2.7% (11/408) (Table 1). This figure is likely to be slightly overestimated, as we excluded from the screening a subset of about 50 probands known to carry pathogenic mutations in other genes.

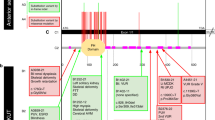

Ten mutations were novel, whereas two (p.R435Q, pR563H) had been previously reported.11 Mutations were homozygous in eight families and compound heterozygous in two. In COR28, only a single mutated allele was found, and genomic qPCR failed to identify deletions or duplications of INPP5E exons. Only one mutation was nonsense (p.Y543X), while the remaining 11 were missense. Nearly all changes were predicted as probably or possibly damaging by Polyphen-2, clustered within the enzymatically active phosphatase domain of the protein and affected residues that were highly conserved among different species (Figure 1). None of the newly identified mutations were encountered among 200 control chromosomes, nor have been previously reported as polymorphisms or rare variants in public databases such as dbSNP, 1000 Genomes, and EVS. All mutations segregated with the disease within families, insofar parents were always heterozygous for one INPP5E mutation while all affected members carried two mutations (with the exception of COR28). In the cohort of 75 MKS fetuses, no pathogenic mutations were found.

Mutations identified in INPP5E. (a) Axial magnetic resonance imaging from six probands with mutations in INPP5E, showing the MTS. (b) Schematic representation of the INPP5E protein consisting of four domains, including a proline rich domain, two small SH3 domains, a large conserved 300-amino-acid catalytic domain and a CAAX domain at C-terminus of the protein. Mutations identified in this article are reported above the panel, while previously described mutations are shown below (the only MORM-associated mutation in shown in italic). Recurrent mutations are shown in bold. (c) Conservation across species (shaded in yellow) of residues affected by the nine novel missense variants.

Phenotypes associated with INPP5E mutations

Detailed clinical features of patients bearing INPP5E mutations are described in Table 1. Seven out of eleven families (64%) presented a phenotype of JS with ocular involvement, consisting of either progressive retinopathy, chorio-retinal colobomas, or both, while the other four families had pure Joubert syndrome, only characterized by neurological signs.

Interestingly, intra-familial variability was observed in some families with multiple affected siblings. For instance, the affected sibs in families COR199 and MTI-1521 were discordant for the presence of either chorio-retinal coloboma or retinopathy. Similarly, the severity of psychomotor delay varied widely in families COR64 and MTI-1521, in which one affected sib presented mild or even absent intellectual deficiency, while the other sibling(s) had a full blown neurological phenotype.

Discussion

Here, we present the first large-scale molecular screening of the INPP5E gene in nearly 500 patients with diagnosis of JSRD or MKS, two ciliopathies allelic at nine loci. Among JSRD, we identified 12 INPP5E mutations of which 10 novel, raising to 16 the number of distinct pathogenic changes so far reported.10, 11 We describe for the first time a homozygous nonsense mutation (p.Y543X), resulting in the production of a truncated protein lacking the final part of the catalytic domain and the C-terminus transmembrane domain. All the remaining mutations are missense changes affecting evolutionarily conserved amino-acid residues clustered within or flanking the enzymatically active phosphatase domain (Figure 1). INPP5E is a member of the 5-ptase family, a class of enzymes that degrade 5-position phosphates from Phosphoinositides (PtdIns), thus regulating diverse cellular processes such as synaptic vesicle recycling, insulin signaling, and embryonic development.15 In particular, INPP5E has been shown to promote ciliary stabilization, and some mutations have been previously shown to alter the INPP5E enzymatic activity and promote premature cilia destabilization in response to specific stimuli.10, 11

Our data indicate a mutation prevalence of about 2.7% among JSRD, while no pathogenic changes were detected in 75 MKS fetuses, suggesting that INPP5E is not causative of the MKS phenotype. Lack of allelism between these two conditions has been already described for other ciliary genes such as ARL13B and CEP41, that are mutated only in JSRD.16, 17 It can be postulated that, at least during embryonic development, the functioning of some ciliary proteins could be less crucial than others or compensated by other proteins acting in the same pathway, insofar even their complete loss of function would not result in a lethal phenotype such as MKS. In fact, the only patient harboring an INPP5E homozygous truncating mutation presented a relatively mild phenotype of JS plus retinopathy and colobomas, arguing against a specific correlation between the protein residual function and phenotypic severity.

Including the present study, a total of 33 INPP5E-mutated patients from 18 JSRD families have been described. Overall, the most common presentation appears to be JS plus ocular involvement, characterized by progressive retinopathy and/or chorio-retinal colobomas (10/18, 56%). Interestingly, in these patients retinal disease was never severe; in fact, none of them presented with Leber congenital amaurosis, that is the typical retinopathy found in patients mutated in CEP290.5 Pure JS is also a frequent presentation, occurring in five families (28%), while other phenotypes such as JS with liver disease (COACH syndrome) and JS with renal disease are extremely rare, being reported only in two and one families, respectively. However, it must be noted that age of examination of some patients was too young to safely exclude the development of a progressive renal disease such as NPH. The INPP5E phenotypic spectrum appears to largely overlap with that related to AHI1 mutations;18 conversely, none of the INPP5E-mutated patients presented polydactyly or encephalocele, two features that are often associated with mutations in genes also causative of MKS, such as TMEM216, CEP290, TMEM67 or RPGRIP1L.5, 19, 20, 21

In one patient with pure JS (COR28), only a single heterozygous INPP5E mutation could be detected, despite complete sequencing of the coding regions and canonical splice sites, and search for genomic rearrangements. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that a second pathogenic mutation resides within intronic or regulatory regions of the gene, it is also plausible that the identified change could act as a genetic modifier of the clinical phenotype in an oligogenic context, and that digenic mutations may reside in another gene. This intriguing mechanism has been already postulated for several ciliopathies including Bardet–Biedl syndrome, NPH and even JSRD,22, 23, 24, 25 and could also help explain the intra-familial variability observed in some INPP5E-mutated families. To this end, the systematic genetic screening of multiple ciliopathy genes based on innovative technologies such as next-generation-sequencing is expected to give a main contribution to clarify the molecular basis underlying the clinical complexity of JSRD and other ciliopathies.

References

Brancati F, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM : Joubert Syndrome and related disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010; 5: 20.

Parisi M, Glass I Joubert Syndrome and Related Disorders: GeneReviewshttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1325/ Initial Posting: 9 July 2003; Last Revision: 14 June 2012.

Srour M, Hamdan FF, Schwartzentruber JA et al: Mutation in TMEM231 cause Joubert Syndrome in French Canadians. J Med Genet 2012; 49: 636–641.

Novarino G, Akizu N, Gleeson JG : Modeling human disease in humans: the ciliopathies. Cell 2011; 147: 70–79.

Brancati F, Barrano G, Silhavy JL et al: CEP290 mutations are frequently identified in the oculo-renal form of Joubert syndrome-related disorders. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 81: 104–113.

Brancati F, Iannicelli M, Travaglini L et al: MKS3/TMEM67 mutations are a major cause of COACH Syndrome, a Joubert Syndrome related disorder with liver involvement. Hum Mutat 2009; 30: E432–E442.

Castori M, Valente EM, Donati MA et al: NPHP1 gene deletion is a rare cause of Joubert syndrome related disorders. J Med Genet 2005; 42: e9.

Bachmann-Gagescu R, Ishak GE, Dempsey JC et al: Genotype-phenotype correlation in CC2D2A-related Joubert syndrome reveals an association with ventriculomegaly and seizures. J Med Genet 2012; 49: 126–137.

Doherty D, Parisi MA, Finn LS et al: Mutations in 3 genes (MKS3, CC2D2A and RPGRIP1L) cause COACH syndrome (Joubert syndrome with congenital hepatic fibrosis). J Med Genet 2010; 47: 8–21.

Jacoby M, Cox JJ, Gayral S et al: INPP5E mutations cause primary cilium signaling defects, ciliary instability and ciliopathies in human and mouse. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 1027–1031.

Bielas SL, Silhavy JL, Brancati F et al: Mutations in INPP5E, encoding inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase E, link phosphatidyl inositol signaling to the ciliopathies. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 1032–1036.

Salonen R : The Meckel syndrome: clinicopathological findings in 67 patients. Am J Med Genet 1984; 18: 671–689.

Travaglini L, Brancati F, Attie-Bitach T et al: Expanding CEP290 mutational spectrum in ciliopathies. Am J Med Genet 2009; 149A: 2173–2180.

DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R et al: A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 491–498.

Dyson JM, Fedele CG, Davies EM, Becanovic J, Mitchell CA : Phosphoinositide phosphatases: just as important as the kinases. Subcell Biochem 2012; 58: 215–279.

Cantagrel V, Silhavy JL, Bielas SL et al: Mutations in the cilia gene ARL13B lead to the classical form of Joubert syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 83: 170–179.

Lee JE, Silhavy JL, Zaki MS et al: CEP41 is mutated in Joubert syndrome and is required for tubulin glutamylation at the cilium. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 193–199.

Valente EM, Brancati F, Silhavy JL et al: AHI1 gene mutations cause specific forms of Joubert syndrome-related disorders. Ann Neurol 2006; 59: 527–534.

Valente EM, Logan CV, Mougou-Zerelli S et al: Mutations in TMEM216 perturb ciliogenesis and cause Joubert, Meckel and related syndromes. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 619–625.

Iannicelli M, Brancati F, Mougou-Zerelli S et al: Novel TMEM67 mutations and genotype-phenotype correlates in meckelin-related ciliopathies. Hum Mutat 2010; 31: E1319–E1331.

Arts HH, Doherty D, van Beersum SE et al: Mutations in the gene encoding the basal body protein RPGRIP1L, a nephrocystin-4 interactor, cause Joubert syndrome. Nat Genet 2007; 39: 882–888.

Khanna H, Davis EE, Murga-Zamalloa CA et al: A common allele in RPGRIP1L is a modifier of retinal degeneration in ciliopathies. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 739–745.

Louie CM, Caridi G, Lopes VS et al: AHI1 is required for photoreceptor outer segment development and is a modifier for retinal degeneration in nephronophthisis. Nat Genet 2010; 42: 175–180.

Davis EE, Zhang Q, Liu Q et al: TTC21B contributes both causal and modifying alleles across the ciliopathy spectrum. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 189–196.

Katsanis N, Ansley SJ, Badano JL et al: Triallelic inheritance in Bardet-Biedl syndrome, a Mendelian recessive disorder. Science 2001; 293: 2256–2259.

Poretti A, Dietrich Alber F, Brancati F, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM, Boltshauser E : Normal cognitive functions in joubert syndrome. Neuropediatrics 2009; 40: 287–290.

Thomas S et al: TCTN3 mutations cause Mohr-Majewski syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2012; 91: 372–378.

Chaki M et al: Exome capture reveals ZNF423 and CEP164 mutations, linking renal ciliopathies to DNA damage response signaling. Cell 2012; 150: 533–548.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported with grants from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente 2012 to EMV, Ricerca Finalizzata 2009 to EB and EMV), the Italian Telethon Foundation (GGP08045 to EB and EMV), the European Research Council (Starting Grant 260888 to EMV), the National Institute of Health (R01NS048453 to JGG), the Broad Institute (U54HG003067 to Eric Lander) for sequencing support and analysis. We thank Dr Celine Gomes and Professor Arnold Munnich for referring patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Other members of the International JSRD Study Group are: L Ali Pacha (Alger, Algeria); A Zankl (Brisbane, Australia); R Leventer (Parkville, Australia); P Grattan-Smith (Sydney, Australia); A Janecke (Innsbruck, Austria); J Koch (Salzburg, Austria); M Freilinger (Vienna, Austria); M D’Hooghe (Brugge, Belgium); Y Sznajer, C Vilain (Bruxelles, Belgium); R Van Coster (Ghent, Belgium); L Demerleir (Brussels, Belgium); K Dias, C Moco, A Moreira (Porto Alegre, Brazil); C Ae Kim (Sao Paulo, Brazil); G Maegawa (Toronto, Canada); I Dakovic, D Loncarevic, V Mejaski-Bosnjak, D Petkovic (Zagreb, Croatia); GMH Abdel-Salam, A Abdel-Aleem, (Cairo, Egypt); I Marti, JM Pinard, S Quijano-Roy (Garches, France); S Sigaudy (Marseille, France); P de Lonlay, S Romano, A Verloes (Paris, France); R Touraine (St Etienne, France); M Koenig, H Dollfus, E Flori, M Fradin, C Lagier-Tourenne, J Messer (Strasbourg, France); P Collignon (Toulon, France); JM Penzien (Augsburg, Germany); C Bussmann (Heidelberg, Germany); A Merkenschlager (Leipzig, Germany); H Philippi (Mainz, Germany); G Kurlemann (Munster, Germany); K Grundmann (Tubingen, Germany); C Dacou-Voutetakis, S Kitsiou Tzeli, R Pons (Athens, Greece); J Jerney (Budapest, Hungary); S Halldorsson, J Johannsdottir, P Ludvigsson (Reykjavik, Iceland); SR Phadke (Lucknow, India); KM Girisha (Manipal, India); H Doshi, V Udani (Mumbay, India); M Kaul (Rajkot, India); B Stuart (Dublin, Ireland); A Magee (Belfast, Northern Ireland); R Spiegel, S Shalev (Afula, Israel); H Mandel (Haifa, Israel); D Lev, M Michelson (Holon, Israel); M Idit (Petach-Tikva, Israel); B Ben-Zeev (Ramat-Gan, Israel); R Gershoni-Baruch (Rambam, Israel); A Ficcadenti (Ancona, Italy); R Fischetto, M Gentile (Bari, Italy); M Della Monica (Benevento, Italy); M Pezzani (Bergamo, Italy); C Graziano, M Seri (Bologna); F Benedicenti, F Stanzial (Bolzano, Italy); R Borgatti, R Romaniello (Bosisio Parini, Italy); P Accorsi, S Battaglia, E Fazzi, L Giordano, L Pinelli (Brescia, Italy); L Boccone (Cagliari, Italy); R Barone, G Sorge (Catania, Italy); E Briatore (Cuneo, Italy); S Bigoni, A Ferlini (Ferrara, Italy); MA Donati (Florence, Italy); R Biancheri, G Caridi, MT Divizia, F Faravelli, G Ghiggeri, M Mirabelli, A Pessagno, A Rossi, V Uliana (Genoa, Italy); M Amorini, M Briguglio, S Briuglia, CD Salpietro, G Tortorella (Messina, Italy); A Adami, MT Bonati, P Castorina, S D’Arrigo, F Lalatta, G Marra, I Moroni, C Pantaleoni, D Riva, B Scelsa, L Spaccini (Milan, Italy); E Del Giudice (Napoli, Italy); K Ludwig, A Permunian, A Suppiej (Padova, Italy); C Macaluso (Parma, Italy); A Pichiecchio (Pavia, Italy); R Battini (Pisa, Italy); M Di Giacomo (Potenza, Italy); M Priolo, P Timpani (Reggio Calabria, Italy); G Pagani (Rho, Italy); ML Di Sabato, F Emma, V Leuzzi, F Mancini, S Majore, A Micalizzi, P Parisi, M Romani, G Stringini, G Zanni (Rome, Italy); L Ulgheri (Sassari, Italy); M Pollazzon, A Renieri (Siena, Italy); E Belligni, E Grosso, I Pieri, M Silengo (Torino, Italy); R Devescovi (Trieste, Italy); D Greco, C Romano (Troina, Italy); M Cazzagon (Udine, Italy); A Simonati (Verona, Italy); AA Al-Tawari, L Bastaki, (Kuwait City, Kuwait); A Mégarbané (Beirut, Lebanon); V Sabolic Avramovska (Skopje, Macedonia); E Said (Msida, Malta); P Stromme (Oslo, Norway); R Koul, A Rajab (Muscat, Oman); M Azam (Islamabad, Pakistan); C Barbot (Oporto, Portugal); MA Salih, B Tabarki (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia); B Jocic-Jakubi (Nis, Serbia); L Martorell Sampol (Barcelona, Spain); B Rodriguez (La Coruna, Spain); I Pascual-Castroviejo (Madrid, Spain); B Gener (Vizcaya, Spain); A Puschmann (Lund, Sweden); L Starck (Stockholm, Sweden); A Capone (Aarau, Switzerland); J Lemke (Bern, Switzerland); J Fluss (Geneva, Switzerland); D Niedrist (Zurich, Switzerland); RCM Hennekam, N Wolf (Amsterdam, The Netherlands); N Gouider-Khouja, I Kraoua (Tunis, Tunisia); S Ceylaner, S Teber (Ankara, Turkey); M Akgul (Izmir, Turkey); B Anlar, S Comu, H Kayserili, A Yüksel (Istanbul, Turkey); M Akcakus, AO Caglayan (Kayseri, Turkey); O Aldemir (Mersin, Turkey); L Al Gazali, L Sztriha (Al Ain, UAE); D Nicholl (Birmingham, UK); CG Woods (Cambridge, UK); C Bennett, J Hurst, E Sheridan (Leeds, UK); A Barnicoat, C Hemingway, M Lees, E Wakeling (London, UK); E Blair (Oxford, UK); S Bernes (Mesa, Arizona, USA); H Sanchez (Fremont, California, USA); AE Clark (Laguna Niguel, California, USA); E DeMarco, C Donahue, E Sherr (San Francisco, California, USA); J Hahn, TD Sanger (Stanford California, USA); TE Gallager (Manoa, Hawaii, USA); C Daugherty (Bangor, Maine, USA); KS Krishnamoorthy, D Sarco, CA Walsh (Boston, Massachusetts, USA); T McKanna (Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA); J Milisa (Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA); WK Chung, DC De Vivo, H Raynes, R Schubert (New York, New York, USA); A Seward (Columbus, Ohio, USA); DG Brooks (Philadephia, Pennsylvania, USA); A Goldstein (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, USA); J Caldwell, E Finsecke (Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA); BL Maria (Charleston, South Carolina, USA), K Holden (Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina, USA); RP Cruse, E Karaca (Houston, Texas, USA); KJ Swoboda, D Viskochil (Salt Lake City, Utah, USA), WB Dobyns (Seattle, Washington, USA).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Travaglini, L., Brancati, F., Silhavy, J. et al. Phenotypic spectrum and prevalence of INPP5E mutations in Joubert Syndrome and related disorders. Eur J Hum Genet 21, 1074–1078 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.305

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2012.305

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Inpp5e Regulated the Cilium-Related Genes Contributing to the Neural Tube Defects Under 5-Fluorouracil Exposure

Molecular Neurobiology (2024)

-

Skeletal ciliopathy: pathogenesis and related signaling pathways

Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (2023)

-

Broadening INPP5E phenotypic spectrum: detection of rare variants in syndromic and non-syndromic IRD

npj Genomic Medicine (2021)

-

Expression patterns of ciliopathy genes ARL3 and CEP120 reveal roles in multisystem development

BMC Developmental Biology (2020)

-

Detecting TF-miRNA-gene network based modules for 5hmC and 5mC brain samples: a intra- and inter-species case-study between human and rhesus

BMC Genetics (2018)