Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Infant and young child feeding (IYCF) has not been documented in central and western China, where anaemia is prevalent. To support policy advocacy, we assessed IYCF and anaemia there using standardized methods.

Subjects/Methods:

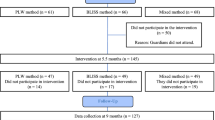

A community-based, cross-sectional survey of 2244 children aged 6–23 months in 26 counties of 12 provinces. Analysis of associations between haemoglobin concentration (HC), IYCF indicators and other variables using crude and multivariate techniques.

Results:

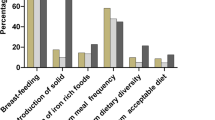

Only 41.6% of those surveyed consumed a minimum acceptable diet. Fewer still-breastfeeding than non-breastfeeding children consumed the recommended minimum dietary diversity (51.7 versus 71.9%; P<0.001), meal frequency (57.7% v. 81.5%; P<0.001) or iron-rich food (63.3% v. 78.9%; P<0.001). Anaemia (51.3% overall) fell with age but was significantly associated with male sex, extreme poverty, minority ethnicity, breastfeeding and higher altitude. Dietary diversity, iron intake, growth monitoring and being left behind by out-migrating parents were protective against anaemia. A structural equation model demonstrated associations between IYCF, HC and other variables. Meal frequency, iron intake and altitude were directly and positively associated with HC; dietary diversity was indirectly associated. Health service uptake was not associated. Continued breastfeeding was directly associated with poor IYCF and indirectly with reduced HC, as were having a sibling and poor maternal education.

Conclusion:

Infant and young child anaemia is highly prevalent and IYCF is poor in rural central and western China. Continued breastfeeding and certain other variables indicate risk of poor IYCF and anaemia. Major policy commitment to reducing iron deficiency and improving IYCF is needed for China’s rural poor.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Benoist B, McLean E, Egli I, Cogswell M . Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2008.

Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health 2013; 1: e16–e25.

UNICEF, UNU, WHO. Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2001.

Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013; 382: 427–451.

Pasricha S-R, Hayes E, Kalumba K, Biggs B-A . Eff ect of daily iron supplementation on health in children aged 4–23 months: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Glob Health 2013; 1: e77–e86.

Pasricha SR, Drakesmith H, Black J, Hipgrave D, Biggs BA . Control of iron deficiency anemia in low- and middle-income countries. Blood 2013; 121: 2607–2617.

United Nations Children’s Fund. Tracking progress on maternal and child nutrition. UNICEF: New York, 2009.

Victora CG, de Onis M, Hallal PC, Blossner M, Shrimpton R . Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics 2010; 125: e473–e480.

Chang S, Wang L, Wang Y, Brouwer ID, Kok FJ, Lozoff B et al. Iron-deficiency anemia in infancy and social emotional development in preschool-aged Chinese children. Pediatrics 2011; 127: e927–e933.

Engle PL, Black MM, Behrman JR, Cabral de Mello M, Gertler PJ, Kapiriri L et al. Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. Lancet 2007; 369: 229–242.

Dewey KG, Adu-Afarwuah S . Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr 2008; 4 (Suppl 1), 24–85.

Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E et al. What works? interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet 2008; 371: 417–440.

Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar AH, Subramanian SV . Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011; 378: 2123–2135.

McDonald SJ, Middleton P, Dowswell T, Morris PS . Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 7: CD004074.

Pasricha SR, Shet AS, Black JF, Sudarshan H, Prashanth NS, Biggs BA . Vitamin B-12, folate, iron, and vitamin A concentrations in rural Indian children are associated with continued breastfeeding, complementary diet, and maternal nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 94: 1358–1370.

National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook. (available in Chinese at http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2011/indexch.htm viewed 18 September 2013), National Bureau of Statistics: Beijing, 2011.

Centre for Health Statistics and Information. China Health Statistics Digest. Beijing, China, 2011.

Wang X, Höjer B, Guo S, Luo S, Zhou W, Wang Y . Stunting and 'overweight' in the WHO child growth standards - malnutrition among children in a poor area of China. Public Health Nutr. 2009; 12: 1991–1998.

Chang S, Chen C, He W, Wang Y . Analysis on the changes of nutritional status in China - the improvement of complementary feeding among Chinese infants and young children. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2007; 36: 19–20.

Guo S, Fu X, Scherpbier RW, Wang Y, Zhou H, Wang X et al. Breastfeeding rates in central and western China in 2010: implications for child and population health. Bull World Health Organ 2013; 91: 322–331.

Chen C, He W, Chang S . The changes of the attributable factors of child growth. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2006; 35: 765–768.

Wang X, C K, Wang Y . Analysis of current situation of breastfeeding and complementary feeding of children aged under 2 years in 105 maternal and child health cooperative project counties. Chin J Child Health Care 2000; 18: 144–146.

Walter CE, Howie F . Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundation of China's Extraordinary Rise. Wiley: Singapore, 2011.

Zeng L, Yan H, Chen Z . Prevalence of anemia among children under 3 years old in 5 provinces in western China. Chin J Epidemiol 2004; 25: 225–228.

Zhang A, Zhang J, Wang Y . Study on anemia of children aged 6-35 months in 46 counties of midwestern China. Chin J Child Health Care 2009; 17: 260–264.

The World Bank. World Development Report 2004: Making Services Work for the Poor People. The World Bank: Washington 2003.

Chen YD, Tang LH, Xu LQ . Current status of soil-transmitted nematode infection in China. Biomed Environ Sci 2008; 21: 173–179.

World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. (Part I - Definitions). Switzerland World Health Organization: Geneva, 2008.

UNICEF. Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys - Round 4. UNICEF: New York, 2010.

World Health Organization. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. (Part II - Measurement). Switzerland World Health Organization: Geneva, 2010.

Ministry of Health WHO UNICEF UNFPA. Joint Review of Maternal and Child Survival Strategy. China Ministry of Health: Beijing, 2006.

Feng X, Guo S, Hipgrave D, Zhu J, Zhang L, Song L et al. China’s facility-based birth strategy and neonatal mortality: a population-based epidemiological study. Lancet 2011; 378: 1493–1500.

Feng XL, Zhu J, Zhang L, Song L, Hipgrave D, Guo S et al. Socio-economic disparities in maternal mortality in China between 1996 and 2006. BJOG 2010; 117: 1527–1536.

Ministry of Health. China Health Statistics Yearbook. Chinese Academy of Medical Science: Beijing, 2012.

Gottret PE, Schieber G . Health Financing Revisited: A Practitioner's Guide. The World Bank: Washington, 2006.

Zhu WX, Lu L, Hesketh T . China's excess males, sex selective abortion, and one child policy: analysis of data from 2005 national intercensus survey. BMJ 2009; 338: b1211.

National Bureau of Statistics. Communiqué of the sixth national census data in 2010 [1]2011. Available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/t20110428_402722232.html (in Chinese, last accessed 18 September 2013).

Senarath U, Dibley MJ . Complementary feeding practices in South Asia: analyses of recent national survey data by the South Asia Infant Feeding Research Network. Matern Child Nutr 2012; 8 (Suppl 1): 5–10.

Ministry of Health. Report on Nutrition Development among Children Aged 0-6 years in China. Beijing, 2012.

Senarath U, Agho KE, Akram DE, Godakandage SS, Hazir T, Jayawickrama H et al. Comparisons of complementary feeding indicators and associated factors in children aged 6-23 months across five South Asian countries. Matern Child Nutr 2012; 8 (Suppl 1): 89–106.

Sun Q, Wang J, Xue M, Sheng X . A cross-sectional analysis of infant and young child feeding and its association with the growth and development infants aged 6 to 8 months old in undeveloped rural China. Chin J Evid Based Pediatr 2009; 4: 499–503.

Lander R, Enkhjargal TS, Batjargal J, Bolormaa N, Enkhmyagmar D, Tserendolgor U et al. Poor dietary quality of complementary foods is associated with multiple micronutrient deficiencies during early childhood in Mongolia. Public Health Nutr. 2010; 13: 1304–1313.

Pasricha SR, Black J, Muthayya S, Shet A, Bhat V, Nagaraj S et al. Determinants of anemia among young children in rural India. Pediatrics 2010; 126: e140–e149.

Malhotra R, Noheria A, Amir O, Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV . Determinants of termination of breastfeeding within the first 2 years of life in India: evidence from the National Family Health Survey-2. Matern Child Nutr 2008; 4: 181–193.

Patel A, Pusdekar Y, Badhoniya N, Borkar J, Agho KE, Dibley MJ . Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in young children in India: secondary analysis of National Family Health Survey 2005-2006. Matern Child Nutr 2012; 8 (Suppl 1), 28–44.

Mangasaryan N, Arabi M, Schultink W . Revisiting the concept of growth monitoring and its possible role in community-based nutrition programs. Food Nutr Bull 2011; 32: 42–53.

World Health Organization and UNICEF. GIVS: Global immunization vision and strategy 2006–2015. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2005.

Domellof M, Lonnerdal B, Dewey KG, Cohen RJ, Rivera LL, Hernell O . Sex differences in iron status during infancy. Pediatrics 2002; 110: 545–552.

Smith RR, Spivak JL . Marrow cell necrosis in anorexia nervosa and involuntary starvation. Br J Haematol 1985; 60: 525–530.

Mishra V, Retherford RD . Does biofuel smoke contribute to anaemia and stunting in early childhood? Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36: 117–129.

Dang S, Yan H, Yamamoto S, Wang X, Zeng L . Poor nutritional status of younger Tibetan children living at high altitudes. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004; 58: 938–946.

Cook JD, Boy E, Flowers C, Daroca Mdel C . The influence of high-altitude living on body iron. Blood 2005; 106: 1441–1446.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China UNSiC. China's Progress Towards the Millennium Development Goals. Beijing, China, 2008.

Kaiman J . Chinese statistics bureau accuses county of faking economic data. The Guardian 2013 7 September 2013.

Zimmermann MB, Chaouki N, Hurrell RF . Iron deficiency due to consumption of a habitual diet low in bioavailable iron: a longitudinal cohort study in Moroccan children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 81: 115–121.

Guldan GS, Zhang MY, Zhang YP, Hong JR, Zhang HX, Fu SY et al. Weaning practices and growth in rural Sichuan infants: a positive deviance study. J Trop Pediatr 1993; 39: 168–175.

Lan X, Yan H . Complementary feeding in 46 rural counties. Chin J Public Health 2003; 19: 918–920.

Lutter CK, Rivera JA . Nutritional status of infants and young children and characteristics of their diets. J Nutr 2003; 133: 2941S–2949SS.

Dewey KG, Brown KH . Update on technical issues concerning complementary feeding of young children in developing countries and implications for intervention programs. Food Nutr Bull. 2003; 24: 5–28.

Gibson RS, Ferguson EL, Lehrfeld J . Complementary foods for infant feeding in developing countries: their nutrient adequacy and improvement. Eur J Clin Nutr 1998; 52: 764–770.

Sun J, Dai Y, Zhang S, Huang J, Yang Z, Huo J et al. Implementation of a programme to market a complementary food supplement (Ying Yang Bao) and impacts on anaemia and feeding practices in Shanxi, China. Matern Child Nutr 2011; 7 (Suppl 3), 96–111.

Wang Y, Chen C, Jia M, Fang J . Effect of complementary food supplements on anemia in infants and young children. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu. 2004; 33: 334–336.

Wang Y, Chen C, Wang F, Wang K . Effects of nutrient fortified complementary food supplements on growth of infants and young children in poor rural area in Gansu Province. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2007; 36: 78–81.

Allen L, de Benoist B, Dary O, Hurrell R Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients. World Health Organization, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Geneva, 2006.

Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Rizvi A, Gaffey MF, Walker N, Horton S et al. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost? Lancet 2013; 382: 452–477.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the provincial, county and township health bureaux in the surveyed locations for their kind assistance. We also thank Sant-Reyn Pasricha of the University of Melbourne for very helpful comments and suggestions during preparation of the manuscript. All opinions expressed are those of the authors only, not their institutions. This survey was funded by UNICEF China. All authors were funded by their parent institutions.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

SG, YW, DBH, XW and HZ designed the research. HZ, XW, YW and SG participated in conduct of the research. XF, YJ, SG and DBH performed statistical analysis. SG, DBH, XF, YJ, HZ, SC and RWS analyzed and interpreted the results. DBH and SG wrote the paper. DBH and SG had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Clinical Nutrition website

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hipgrave, D., Fu, X., Zhou, H. et al. Poor complementary feeding practices and high anaemia prevalence among infants and young children in rural central and western China. Eur J Clin Nutr 68, 916–924 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.98

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.98

This article is cited by

-

Infant and young child feeding practices are associated with childhood anaemia and stunting in sub-Saharan Africa

BMC Nutrition (2023)

-

Minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among children aged 6-23 months in Enebsie Sar Midir Woreda, East Gojjam, North West Ethiopia

BMC Nutrition (2022)

-

The association between parental migration and early childhood nutrition of left-behind children in rural China

BMC Public Health (2020)

-

Anemia in disadvantaged children aged under five years; quality of care in primary practice

BMC Pediatrics (2019)

-

Maternal haemoglobin concentrations before and during pregnancy as determinants of the concentrations of children at 3–5 years of age: A large follow-up study

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2019)