Abdul Ghaffar Shar, a student from Pakistan on a scholarship at Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, discusses irrigation with Li Haiping.Credit: Xinhua/Alamy

Chinese science is facing change. Tensions with the United States along with the COVID-19 pandemic look set to accelerate a drive towards research self-sufficiency and talent repatriation.

Since 2014, China has enjoyed a net inflow of scientific talent, reversing the trend of the previous four decades, which saw more researchers leaving than arriving, an analysis of half a million scholars at the 100 leading institutions in the Nature Index reveals.

Research carried out for Nature Index by League of Scholars, an academic data and recruitment firm in Sydney, Australia, also finds that more than 10% of academics at Chinese universities, as of March 2021, arrived from abroad in the previous three years, a proportion close to triple the global average of 3.7%. Many of these globetrotting scholars are returning Chinese citizens.

The increase in students and researchers returning to China from the West accelerated greatly in 2020, says Marijk van der Wende, professor of higher education at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. “Many members of this diaspora are returning, often with advanced degrees and research experience,” says van der Wende, who co-edited a book on China’s higher-education globalization strategy (China and Europe on the New Silk Road: Connecting Universities Across Eurasia Oxford Univ. Press; 2020).

Van der Wende expects that this will allow China to capitalize on sustained and systematic investments in higher education and research, “even more so because it seems to be coming out of the economic consequences of the pandemic much faster than Europe”.

China’s pool of 1.12 million full-time equivalent researchers is nearly as big as the European Union’s post-Brexit (1.13 million), and exceeds that of the United States (1.10 million), according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development figures for 2020. In Elsevier’s Scopus database, China surpassed the United States in research output in 2016. Across several fields, including nanotechnology, biotechnology and chemistry, it has more than 20% of the institutions in the top 50 for Academic Ranking of World Universities academic subjects. “China has moved, very fast, to a very strong technological and scientific power,” says van der Wende.

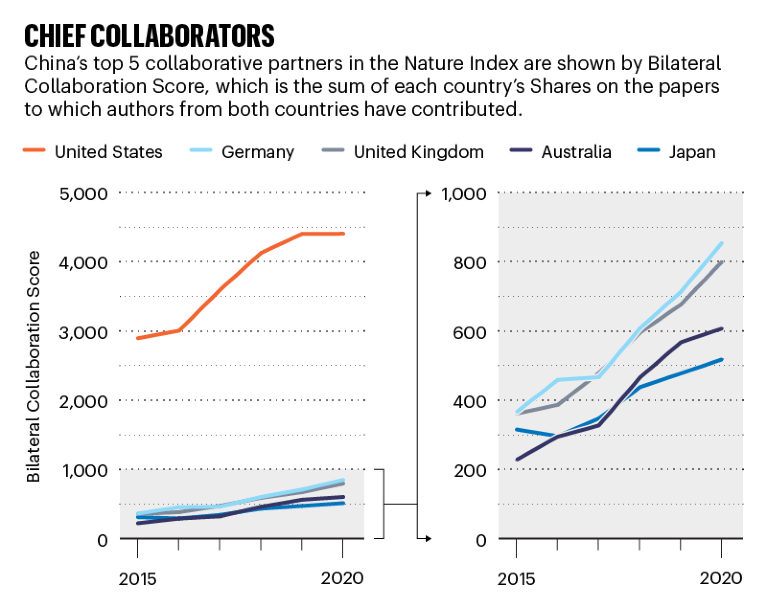

In the Nature Index, China has the highest Share for chemistry, and is second only to the United States in the physical sciences, life sciences, and Earth and environmental sciences. Its annual average increase in adjusted Share of 13.1% was the greatest of all leading scientific nations from 2016 to 2019, but slowed substantially in 2020 to 1.1%. Zero growth in its collaborative publications with the United States in 2020 and a government push favouring publication in Chinese journals may be contributing factors.

Source: Nature Index

Returning scientists boost the country’s research output. On average, their rate of overall publications nearly doubled upon their return, according to a 2020 study (Z. Zhao et al. J. Informetr. 14, 101037; 2020). “The competition in Chinese universities makes returnees work very hard to publish papers because they have to survive,” says co-author Jiang Li, a scientometrician at Nanjing University, China.

The study also found that returning Chinese researchers publish in top journals (defined as Nature, Science, Cell and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) about half as often as those who remain overseas. Li attributes this in part to pressure from China’s output-driven system, as researchers focused on quantity of output may not have the time or resources to conduct the type of detailed, lengthy experiments that could lead to a breakthrough publication.

China is making a concerted effort to attract scientific talent. Although the typical university professor earns less than US$50,000 a year, Chinese universities offer incentives such as housing allowances and childcare assistance, which make the positions highly sought-after, says Li.

But returned scientists’ valuable role in building international collaborations faces problems. Scientists in the United States, Australia and Europe are currently shying away from forming partnerships with their Chinese peers for fear of becoming entangled in geopolitical tensions and, in the United States and Australia, because of onerous new regulations on the disclosure of foreign research ties.

Fresh twists in China’s bid for research dominance

Fresh twists in China’s bid for research dominance

Superpowered science: charting China’s research rise

Superpowered science: charting China’s research rise

Five science stars making their mark in China

Five science stars making their mark in China

China’s leading researchers set their sights on new frontiers

China’s leading researchers set their sights on new frontiers

Chinese joint-venture universities try for the best of both worlds

Chinese joint-venture universities try for the best of both worlds