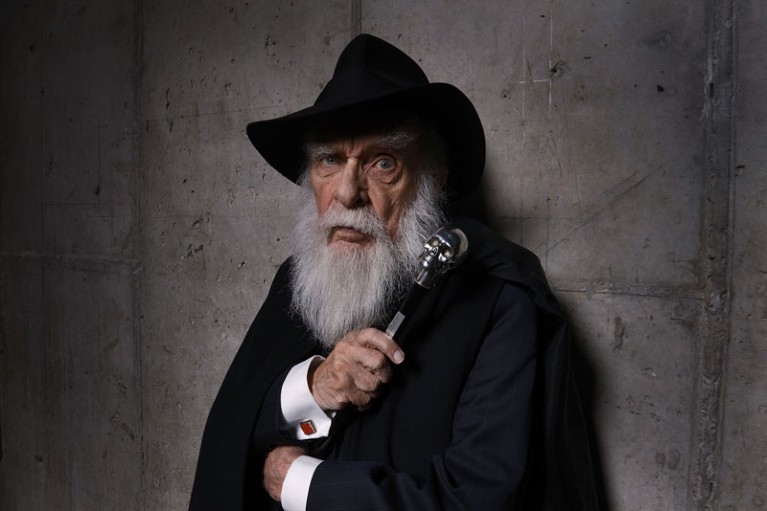

Credit: Larry Busacca/Getty Images for the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival

The illusionist James Randi devoted much of his career to debunking frauds. Seen as a lodestar by the ‘sceptical movement’ that confronts superstition and magical thinking with science and rationality, he famously collaborated with an editor of this journal, yet would also have found a receptive audience in medieval courts and Victorian theatres. That such individuals are needed now more than ever is a reminder that advances in science don’t banish credulity, but create new stages for it.

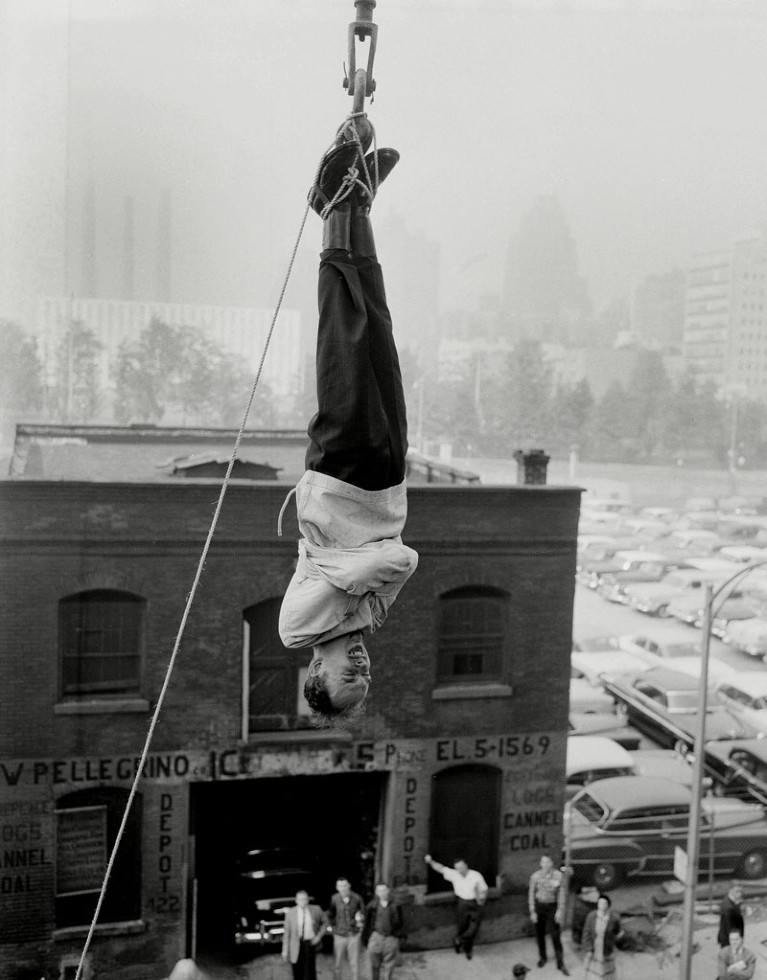

A precociously gifted child, Randi (born Randall James Zwinge in Toronto, Canada, in 1928) developed an enthusiasm for stage magic. In his teens he literally ran away to join the circus, becoming a ‘mind reader’ and an escape artist. In the 1970s, his taste for spectacle found him touring with theatrical rock star Alice Cooper, whom he ‘executed’ at the end of each show.

Like many who investigated spiritualism and seances before him, Randi was keen to be seen as a sceptic rather than as someone on a mission to disprove. He challenged faith-healers, psychics and believers in UFOs, and in 1976 he joined with mathematician Martin Gardner, planetary scientist Carl Sagan and science-fiction author Isaac Asimov to found the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. The organization still publishes Skeptical Inquirer, a magazine devoted to the scientific investigation of paranormal or otherwise extraordinary claims.

The idea that stage magic can be used to debunk superstition and psychic fraud was familiar in the nineteenth century. Illusionist shows by the likes of John Henry Pepper at London’s Egyptian Hall were also popular demonstrations of the wonders made possible by optics and electromagnetism. In the early twentieth century, John Nevil Maskelyne, a founder of the UK Magic Circle, took on deceivers such as the spiritualists Ira and William Davenport and theosophists such as Helena Blavatsky. He also showed how the Indian rope trick, which turns a rope into a rigid pole, can be done without recourse to occult powers.

Following the tradition of the Magic Circle, whose members disavow any claim to mystic powers (although they do not reveal their methods), Randi dubbed himself an “honest liar”, the title of a 2014 documentary on his life and work. Frankness about the nature of magical stagecraft goes back at least to the Elizabethan Reginald Scot’s assertion in The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) that honest jugglers and prestidigitators “always acknowledge wherein the art consisteth”.

James ‘The Amazing’ Randi used stage magic and theatre to debunk superstition and promote scepticism.Credit: Anthony Camerano/AP/Shutterstock

One of Randi’s most enduring adversaries was the British Israeli illusionist and self-styled psychic Uri Geller. A regular on 1970s TV, Geller would demonstrate his skills memorably in ‘psychokinetic’ spoon-bending. The two men developed a strangely symbiotic relationship. Randi exposed Geller’s deceptions in his 1975 book The Magic of Uri Geller; undaunted, Geller regarded their sparring as good publicity.

Geller’s feats looked underwhelming to anyone who had witnessed Randi in action. I recall an impromptu demonstration at Nature’s office in the late 1980s, when he produced a very plausible sketch of a word plucked by an editor at random from past volumes of the journal. (It happened to be ‘position’.)

Randi’s involvement with Nature began when then-editor John Maddox enlisted him to investigate a claim by French immunologist Jacques Benveniste, who had found recurrent biological activity in a solution of antibodies diluted well past the point at which any active ingredient should remain. This alleged “memory of water”, published in Nature in 1988, seemed to offer support for homeopathy.

Randi, Maddox and US National Institutes of Health biologist Walter Stewart, a specialist in scientific misconduct, went to Benveniste’s laboratory near Paris to witness a repeat of the experiments. Randi created an element of theatre by taping the code identifying the samples for blind testing to the ceiling — not so much to prevent tampering, he later explained, but to see if anyone would make the attempt. The episode added to the notoriety of the original claim: one correspondent said it confirmed his suspicion that “Papers for publication in Nature are refereed by the Editor, a magician and his rabbit.” Benveniste’s findings were largely dismissed after he (and others) proved unable to replicate them.

Randi courted that kind of controversy all his life. Some felt that the sage-like beard and wizard-style hats detracted from his debunking mission. But Randi was mindful of the lessons of history: spectacle need not compromise rationality, but can be enlisted in its service. Since the 1960s, he had offered substantial sums to anyone who could demonstrate paranormal or psychic powers — a stunt Maskelyne instigated. From 1996 until the prize was terminated in 2015, the James Randi Educational Foundation raised the stakes to US$1 million.

Although quacks and psychics are still in business (and probably always will be), today the biggest danger of deception comes in a form that can threaten lives, nations and international structures: disinformation. From conspiracy theories to deep-fake videos, the descendants of medieval mountebanks ply their wares online, sometimes packaged in ways that mislead even astute audiences. Randi surely saw the ‘infodemic’ coming, but it has proved an infinitely more insidious opponent than the con artists of stage and screen.

Randi died aged 92. His central message is as important for scientists as for everyone else: “Don’t be too sure of yourself. No matter how smart or well educated you are, you can be deceived.”

The memory of water

The memory of water

History: Impractical magic

History: Impractical magic

The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories

The epic battle against coronavirus misinformation and conspiracy theories

Elixirs for times of plague and bullion shortage

Elixirs for times of plague and bullion shortage