EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler says that the United States has made “incredible strides in reducing particulate matter concentrations” — as he oversees the revision or cancellation of more than 80 rules and regulations.Credit: Alex Brandon/AP/Shutterstock

Why are those at the helm of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continuing to roll back key environmental and public-health regulations? Why are they making it harder for themselves — and future administrations — to craft new regulations based on all of the available research? And why, in their actions, do they continue to challenge the place of rigorous evidence in policymaking?

We need to keep asking these questions, because, although the world’s attention is rightly focused on the coronavirus pandemic, in the past six weeks alone, the agency’s leaders have accelerated moves to weaken research-based regulations.

They are walking a road that the EPA’s founders — who launched the agency 50 years ago — could not have imagined the organization would take. In spite of reasoned opposition from researchers and many businesses, too, the EPA’s leadership — with the tacit support of many Republicans in the US Congress — is undermining the very reasons for its own existence. This is a travesty.

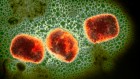

The latest target is the well-established body of evidence that demonstrates how tiny airborne particles embed themselves deep in the lungs and increase the risk of premature death from respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

Five ways that Trump is undermining environmental protections under the cover of coronavirus

In a report published last September, the EPA’s staff reviewed recent literature, including research indicating that even low levels of particulate pollution contribute to premature deaths in the United States. The report concluded that such evidence justified reducing the maximum permitted concentrations of fine particulate matter from 12 micrograms per cubic metre of air to between 8 and 10 micrograms. But on 14 April, the agency’s administrator, Andrew Wheeler, said that there is no need for change. No reasoning was provided for this decision except that: “The U.S. has made incredible strides in reducing particulate matter concentrations across the nation.”

Two days later — in a different sphere of regulation — the EPA confirmed a change to the valuation methodology for regulations curbing the emissions of mercury and other pollutants from fossil-fuel-fired power plants — a change that could have far-reaching consequences for people and the environment.

Enforcing existing mercury standards costs the US utilities industry up to US$10 billion annually. In 2015, the administration of Barack Obama calculated that, in addition to preventing up to 11,000 premature deaths in the United States, these standards also save the country in the range of $37 billion to $90 billion a year — money that would otherwise be spent on, for example, extra health-care costs. But the EPA’s leadership brushed aside the research and data that support these findings. The EPA is currently considering new guidance that would allow it to ignore such comprehensive assessments of comparisons of costs versus benefits — leading to potentially weaker environmental and public-health regulations in other areas, too.

On top of all this, in March the administration of US President Donald Trump finalized a revised set of targets governing greenhouse-gas emissions from new vehicles. It slashed the original ambition of 5% in annual reductions to 1.5%. (By contrast, the European Union’s target is for a 27% reduction, compared with its 2015 target, in carbon emissions per kilometre from cars manufactured after 2020.)

Controlling the science

Each of these revisions builds on the Trump administration’s overarching narrative since 2017: to control the research that is used as evidence for the EPA’s decisions. This began with a proposed rule that is misleadingly called Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science. In reality, it is a declaration that the EPA intends to limit its use of studies for which underlying data and models are not publicly accessible. This move has provoked widespread condemnation from researchers and searching questions from the EPA’s own science advisory board. The rule, if implemented as written, could allow the agency to disregard landmark public-health studies for which underlying data — such as confidential health records — are not accessible for good reasons.

Science under siege: behind the scenes at Trump’s troubled environment agency

In all, more than 80 EPA rules and regulations are being revised or removed, and researchers have been campaigning and protesting as never before. They must continue to do so, working with allies in industry and across other sectors. It can be difficult and frustrating when the doors to reasoned engagement are closing. But it is, nevertheless, crucial to push back, so that the agency can be rebuilt when — not if — the time comes.

When the EPA disbanded one of its air-quality science advisory panels in 2018, the panel’s members reconvened independently to continue their work, and issued a statement advising the agency to strengthen the particulate-matter standard. And when the agency refused to hold an evidence session on its proposed ‘transparency’ rule, members of the Union of Concerned Scientists, a science advocacy group based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, organized their own public hearing.

Some familiar names in industry also no longer wish to be associated with regulatory decisions they know will be harmful — and are choosing to stand with the science. Automobile manufacturers Ford, BMW, Honda and Volkswagen have said that they wish to comply with the stricter vehicle-emissions standards developed by the state of California. Some power corporations that have already invested in meeting existing regulatory standards are also unwilling to roll back.

The EPA is becoming a shell of its former self. Its leaders have chosen to abdicate leadership, disregard evidence and expose the country’s environment and health to risk of further degradation. Many staff have understandably chosen to leave. Those who remain should know that they have supporters around the world, rooting for them and for the EPA — and hoping that, one day, it will once again become an evidence-based body that lives up to its name and secures its founders’ legacy.

Science under siege: behind the scenes at Trump’s troubled environment agency

Science under siege: behind the scenes at Trump’s troubled environment agency

Five ways that Trump is undermining environmental protections under the cover of coronavirus

Five ways that Trump is undermining environmental protections under the cover of coronavirus