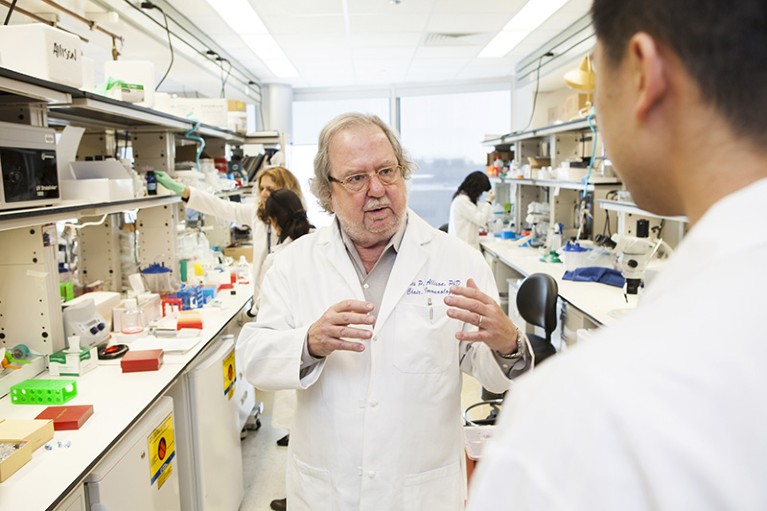

James Allison pioneered the antibody-based cancer treatment ipilimumab.Credit: Scott Dalton/The New York Times/eyevine

Breakthrough Director: Bill Haney Uncommon Productions (2019)

Born in sleepy Alice, Texas, in 1948, James Allison overcame myriad obstacles to develop a new form of cancer treatment. In 2018, at the age of 70, he won a Nobel prize for it. Now, the documentary Breakthrough traces the trajectory of the tumour immunotherapy that he pioneered.

Directed by award-winning filmmaker and sustainability entrepreneur Bill Haney and narrated by actor Woody Harrelson, the film offers a straightforward look at Allison’s life. But viewers should take heed: Haney is also the co-founder and chief executive of a cancer-immunotherapy company, albeit one that takes a different approach from Allison’s. Some members of that company’s scientific advisory board loom large in the documentary.

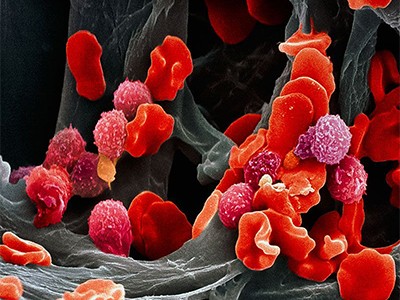

Still, the film gives some sense of how Allison’s passionate advocacy for the cancer drug he helped to develop kept it from being lost in the reject piles of the pharmaceutical industry. The US Food and Drug Administration approved ipilimumab (Yervoy) to treat advanced melanoma in 2011. This was the first drug to unleash the immune system against cancer by blocking ‘checkpoint proteins’, which restrain immune responses. Tumours sometimes rely on these proteins to hide from the body’s defences.

The return of cancer’s magic bullet

Since then, similar drugs have emerged, revolutionizing cancer treatment. A few patients have experienced remissions long enough for some physicians to use the controversial word ‘cure’. But I winced when the documentary framed Allison’s drug as a cancer cure right off the bat. Less than one-quarter of people with advanced melanoma respond to ipilimumab. Success rates are even lower for many other tumour types, including breast and prostate cancers.

Still, the approach has saved thousands of lives. And Allison fought hard for that. His tenacity was already evident when, as a teenager, he demanded that his high school teach evolution in its biology classes. This incurred the wrath of a science teacher whom Allison once revered. The man began to beat him — out of spite, Allison speculates — but Allison didn’t back down. “If you don’t agree with something, you need to stand your ground,” he says. “And if it hurts, it hurts, you know? That’s the way it is.”

That resolve, coupled with his intellect and a clear creative streak, propelled him through his scientific career. Allison eventually settled on immunology, trying to find out how protective T cells recognize cells that don’t belong in the body, marking them for destruction. Initial studies pinpointed a protein called CTLA-4, which seemed to be important for activating T cells. Allison was sceptical. “I saw some holes in that paper,” Allison says he told his lab.

He and his colleagues, along with others, later showed that CTLA-4 actually suppresses T cells. Allison then reasoned that tumours might use the protein to prevent the immune system from attacking cancer cells. He was right, but convincing pharmaceutical companies that this could be a path to a profitable drug took years. Cancer immunotherapy had a poor reputation after an initial splash of hype in the 1980s yielded disappointment.

Through it all, Allison partied hard. We see him in a sombrero, swigging tequila from the bottle. He was known for carousing all night, then hauling himself back to the bench the following morning with the same gusto. There are shots of him playing the harmonica (he has accompanied country-music star Willie Nelson, and heads a blues band, the Checkmates).

This is documentary at its most stylistically simple: colleagues telling stories and singing his praises, stills from Allison’s past, random footage of anonymous researchers in laboratories. The narration sometimes feels a little out of place, as do some of the lab shots. (I spotted footage of a plant biologist I used to know, swirling a flask of algae — a bit odd in a movie about cancer.) But the film more than makes up for small oversights by pulling back the curtain on what was happening inside pharma while Allison waged his campaign to get ipilimumab into clinics.

Rachel Humphrey, now chief medical officer at CytomX Therapeutics in South San Francisco, California, emerges as an unsung hero of the effort. She laid her career on the line, even changing companies when one refused to take on ipilimumab. She finally found a firm that was willing to foot the bill for large clinical trials: Bristol-Myers Squibb of New York City.

When the first tranche of data came in, showing that tumours were not immediately shrinking in response to the drug, Humphrey battled hard through boardroom shouting matches to get the company to invest in longer trials to evaluate whether the drug improved overall survival. It was those trials that lead to ipilimumab’s approval.

Breakthrough is unashamedly hagiographic, but it does make a lovely motivational film for bench scientists. There is the familiar ‘They said it couldn’t be done!’ trope, and a hefty dose of solid science triumphing over short-term business interests. “This is what a hero looks like,” says the film poster, over a photo of Allison standing at a microscope.

At the end, we see Allison, himself now a cancer survivor, quietly weeping as he reads a letter of thanks from a woman whose husband, diagnosed with advanced melanoma, was saved by immunotherapy. (“I need a drink,” he says afterwards.) Tinged with schmaltz it may be, but this was what Allison spent decades in the scientific wilderness to accomplish.

The return of cancer’s magic bullet

The return of cancer’s magic bullet

Pioneer of polio eradication

Pioneer of polio eradication

Up close and personalized

Up close and personalized

Magic bullets to blockbusters

Magic bullets to blockbusters