Residents of the Yanyuan community for senior citizens, in Beijing, take a dance class. China's ageing population is set to challenge the country's health-care system.Credit: Greg Baker/AFP/Getty

Chunying Chen remembers the first nanomedicine conference held in China, which took place in 2015. “It was small. Just 500 people,” she says. “Three years later, it had almost tripled in size.”

In the past decade, the chemist has also seen her budget for research into how to use nanomaterials to diagnose and treat malignant tumours triple. Her country is investing increasing amounts of money into materials research that relates to health care. Areas such as drug delivery, bone regeneration and tissue repair all rely on advanced biomaterials research, for example.

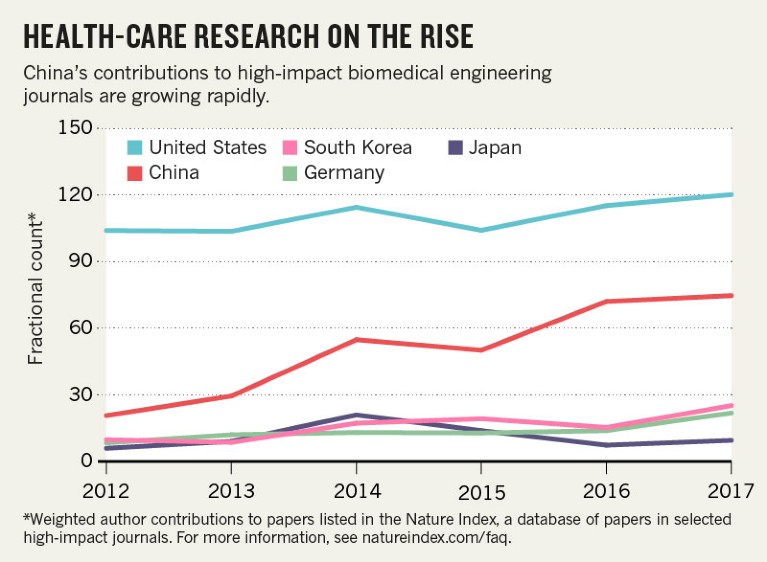

China is playing catch-up when it comes to improving the quality of its national health-care system, from funding bench research to improving patient services (see ‘Health-care research on the rise’). Although the government has increased its expenditure over the past decade, it still spends only 6% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, up from 4% in 2007, compared with the average 9.6% spent by the United Kingdom, or the 17% spent by the United States.

For the past two decades, Chen, who works at the National Center for Nanoscience and Technology in Beijing and won one of China’s top science prizes, the National Natural Science Award, in 2018, has become aware of how keen government officials are for her research to bear tangible results.

Over the past year and a half, she has been working with a company to determine how to produce nanomaterials on a large scale to prepare for preclinical trials.

“China has recently become very focused on promoting the translation of basic research. Grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology include a requirement for translation,” says Chen.

Nature Spotlight on Materials Science in China

Chinese scientists who have moved abroad to continue their careers can see the difference back home. Zhen Gu graduated from Nanjing University in 2006 and moved to the United States to undertake a PhD. Back then, he felt the quality of biomaterials science was significantly lower in China. Now, he’s not sure which country has the bigger research potential.

“The need from China for advances in these fields is tremendous,” says Gu, a chemist who studies drug-delivery systems at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The population is huge and the market is there. People have higher incomes, are living longer and have a growing awareness of the importance of health and quality of life. For them, the biomaterials field is essential. Perhaps more so than in the States.”

China’s development of health care is tied to a national plan called, Made in China 2025, to reform and modernize the country’s manufacturing industries. By 2025, the country wants to make high-tech health-care products and rely less on foreign imports.

Xiyun Yan, a nanomedicine researcher at the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, has spent her career in China, Germany and the United States. Yan is working with two companies on applications for her work on nanozymes — nanomaterials with enzyme-like activity. In 2007, Yan showed that at the nanoscale, iron oxide can mimic the activity of peroxidases — naturally occurring enzymes found in a wide variety of organisms that have a role in many biochemical processes (L. Gao et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 2, 577–583; 2007).

Yan’s group has successfully integrated these nanozymes into systems for detecting biomarkers of pathogens such as the Zika virus, and of cancers. In 2018, the China Food and Drug Administration approved the production of nanozyme-based tests that could detect infectious diseases and biomarkers for tumours.

Twenty years after returning to China, Yan says the environment for her research is very different. Back then, she was given enough funding “for one computer and a table”, she says. “Now we have 100 times more.”

But funding aside, for Yan, the biggest change has been in attitudes to her work. “Before, all anyone cared about was publishing papers in Nature or Science. But now, people think about how the science will be used, and whether the research will solve a problem.”

Materials science is helping to transform China into a high-tech economy

Materials science is helping to transform China into a high-tech economy

The Chinese researcher painting the printing industry green

The Chinese researcher painting the printing industry green

High-pressure research and a return to China: meet Haiyan Zheng

High-pressure research and a return to China: meet Haiyan Zheng