Steinhardt Museum of Natural History Tel Aviv, Israel. Preliminary opening from 2 July.

A glass case crammed with a glorious jumble of stuffed animals and birds greets me as I enter the atmospheric Treasures of Biodiversity gallery at the new Steinhardt Museum of Natural History in Tel Aviv, Israel. This cabinet of curiosities contains century-old specimens collected by German ornithologist Ernst Schmitz. In 1908, Schmitz travelled to Jerusalem — then part of the Ottoman Empire — and opened a natural history museum showcasing a spectacular collection of rare mammals, butterflies and other insects, reptiles and birds’ eggs, many gathered by local Bedouin people. These riches are now on display among the museum’s vast holdings.

The museum features specimens collected a century ago by priest and ornithologist Ernst Schmitz.Credit: Tamar Zadok/TEVA TAU-NHMS

“This is the last Nile crocodile in Israel,” says Tel Aviv University zoologist Tamar Dayan, chair of the museum and the driving force behind its creation. “This is the last cheetah in Israel. The leopard comes from the Judean Mountains, from a population that no longer exists. This is the last oryx in Israel, and the last bearded vulture. We have a lot of ‘lasts’ here.” The glass case encapsulates the loss of many species — a full third of the large mammals in what is now Israel. Conveying the magnitude of this change is a key part of the museum’s mission.

In the Web of Life section, animals gather around the acacia tree that supports their ecosystem.Credit: Tamar Zadok/TEVA TAU-NHMS

In this, it succeeds. Much of the exhibition space is inevitably allocated to displaying some of its 5.5 million skeletons and other specimens of flora and fauna, previously dispersed over the campus of the adjacent Tel Aviv University. But the causes of biodiversity loss in Israel are also front and centre. Charts in Hebrew, English and Arabic deliver the facts on climate change, habitat destruction, invasive species, pollution and over-exploitation of marine resources. A 6-metre-long interactive map of the region enables visitors to witness a century and a half of environmental impacts. For example, over-use of water has indirectly shrunk the Dead Sea, and unchecked construction has destroyed some two-thirds of Israel’s coastal sand dunes since the country was established in 1948. It points, too, to the impacts of invasive species, pollution and hunting.

Some two decades in the making, the museum itself is an architectural jewel, designed by Kimmel Eshkolot Architects in Tel Aviv to resemble a treasure chest. The light-filled building — partly surrounded by an ark-like façade of wood veneer — can be navigated entirely on ramps and walkways, and is fully accessible for wheelchairs and prams. As at the Darwin Centre in London’s Natural History Museum, visitors can gaze through windows beyond the taxidermy to watch scientists studying taxonomy and systematics, biogeography and ecology, invasion biology, evolution, zooarchaeology, archaeobotany and more. Five hundred researchers will work in the museum.

Hyenas and other carrion eaters in a section called Nature’s Sanitation Department.Credit: Tamar Zadok/TEVA TAU-NHMS

The ramp system drew some criticism at the design stage from people concerned that it would encourage children to run around. Architect Michal Kimmel Eshkolot thinks that this is a good thing: public buildings, she tells me, “should be friendly to people, inviting, the opposite of intimidating”.

Children are just as likely to be mesmerized by the exhibits. The Form and Function room is filled with artfully mounted animals — including a caracal leaping to capture a ground-dwelling bird called a black francolin — and the skeletons of native and non-native mammals and birds. A replica velociraptor hangs from the ceiling (although, as Dayan admits, the only traces of dinosaurs found in Israel are footprints). Bugs and Beyond celebrates entomology, including cases filled with live Madagascar hissing cockroaches, giant stick insects and pinned tarantulas and butterflies of all colours and sizes. Kids can also watch a video of a dead rodent decomposing in half a minute, its fur and bones replaced by grass and a graceful toadstool.

A caracal catches a black francolin in the Form and Function room.Credit: Tamar Zadok/TEVA TAU-NHMS

Creative use of space is integral. Six shallow dioramas showcase the mammals, birds and insects found in six Israeli habitats: desert, sandy, aquatic, Mediterranean woodland and scrubland, the Hermon mountains and non-native, fire-prone pine plantations. A cast of a giant minke whale skeleton (in whose bones pigeons nest) hangs in an alcove open to the sky.

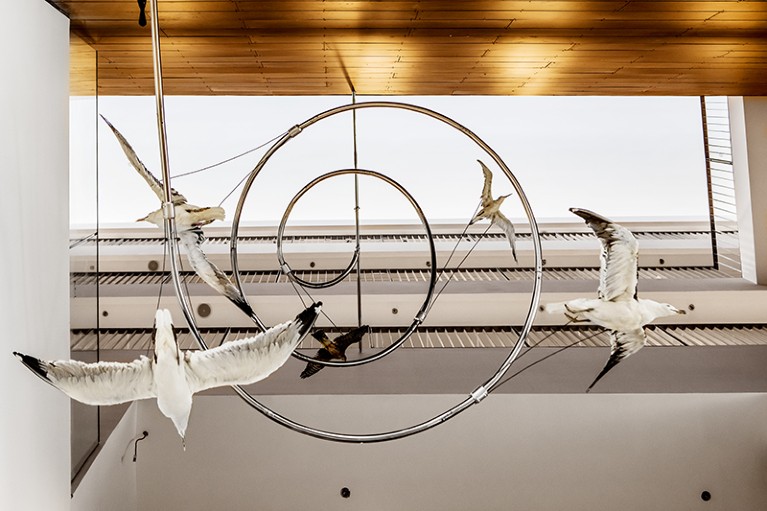

The museum’s most dramatic display is also airborne. The Great Bird Migration is a swirl of avian travellers soaring high above our heads in the great entrance hall. Among them are the common crane, grey heron, greater flamingo, osprey, white stork, great white pelican and black kite. They represent some of the 500 million birds that fly over Israel in spring and autumn. Many are listed among the winged creatures that the Hebrew Scriptures’ book of Leviticus prohibits the Israelites from eating. It’s a reminder, perhaps, that these birds have been present in the region for thousands of years and probably much longer. And that, if we do not protect them, this is how they will end up: stuffed.

The Great Bird Migration display in the museum’s entrance hall.Credit: Tamar Zadok/TEVA TAU-NHMS

Backstage at the museum

Backstage at the museum

Museums: A natural evolution

Museums: A natural evolution

The endangered dead

The endangered dead