Abstract

Previous studies have demonstrated that besides the classic canonical transient receptor potential channel family, Orai family and stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1) might also be involved in the regulation of store-operated calcium channels (SOCCs). An increase in cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration promoted by store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) is a major trigger for pulmonary vasoconstriction and proliferation and migration of PASMCs. In this study, our data revealed the following: (1) in both rat distal pulmonary arteries and PASMCs, chronic hypoxia exposure upregulated the expression of Orai1 and Orai2, without affecting Orai3 and STIM1; (2) either heterozygous knockout of HIF-1α in mice or knockdown of HIF-1α in PASMCs abolished the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2, but not Orai1, suggesting the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2 depends on HIF-1α; and (3) using small interference RNA knockdown strategies, Orai1, 2, 3 and STIM1 were all shown to mediate SOCE in hypoxic PASMCs. Together, these results suggested that the components of SOCCs, including Orai1, 2, 3 and STIM1, may lead to novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to consensus of the Fifth World Symposium of Pulmonary Hypertension held in Nice, France, in 2013, chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension (CHPH) belongs to group 3 of pulmonary hypertension (PH). PH group 3 is due to lung diseases and/or hypoxia, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, sleep-disordered breathing, alveolar hypoventilation disorders, diffuse parenchymal lung diseases, chronic exposure to high altitude and developmental abnormalities.1

CHPH is characterized by excessive contraction, proliferation and migration of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), which progressively leads to the thickening and remodeling of distal pulmonary arteries (PAs). The increase of intracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) is a major trigger for pulmonary vasoconstriction and the proliferation and migration of PASMCs.2 Among the multiple pathways that can lead to increase in [Ca2+]i, the hypoxia-induced enhanced store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) through store-operated calcium channels (SOCCs) largely accounts for the elevated [Ca2+]i in PASMCs.3,4 SOCCs are mainly constituted by canonical transient receptor potential channel (TRPC) and calcium release-activated calcium modulator (also called Orai).5–8 Orai consists of three members, Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3. Recent studies have revealed that Orai1 might be involved in the constitution of SOCCs, or regulates the function of SOCCs.6,7,9 In mesenteric artery smooth muscle cells, the expression level of Orai members are upregulated in proliferating cells.10 Orai1 consists of four transmembrane domains. Under resting conditions, Orai1 exists either as a homodimer or homotetramer; while upon activation, it forms a hexamer and mediates Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ current (ICRAC), a highly Ca2+-selective and nonvoltage-gated current.11–15 The activation kinetics of Orai1 are relatively slow and determined by the rate of Ca2+ depletion as well as the translocation rate of both STIM1 and Orai1 to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)–plasma membrane (PM) junctions. The duration of Orai1 activation can be sustained with prolonged store depletion.16 Among the three Orai homologs, Orai1 contributes the most to mediate SOCE.17 Soon after Orai1 was discovered in 2006, Orai2 was reported as another component of SOCCs.17–19 Similar with Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3 are highly Ca2+ selective corresponding to the characteristic of CRAC (Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+) channels.20,21 Orai3 was only found in mammals, with a tissue distribution at least as wide as that of Orai1.22,23 Orai3 combines with Orai1 to form a hexameric CRAC channel, and at least one native Orai1 subunit is contained in the complex.24 Orai1 and Orai3 arrange as pentamer to form the arachidonic acid-regulated calcium (ARC) channels, whose characteristics are similar to CRAC channels, but are store-independent.25 However, whether the Orais contribute to hypoxia-induced enhancement of SOCE remains largely unknown.

Stromal interaction molecule 1 (STIM1), a single-pass transmembrane protein, has been well known to predominantly localize in the ER/SR membrane where it acts as a Ca2+ sensor and mediates SOCE.26–28 Global deletion of STIM1 in mice is lethal indicating that STIM1 is indispensable in organismal physiology of mammals.29 The homolog STIM2 shares 61% structural homology with STIM1.30 When Ca2+ depleted in ER/SR calcium pool, STIM1 departs ER/SR membrane and translocates to cell membrane, where it activates SOCCs and initials the SOCE.5,26,31 Previous studies have reported in HEK293, epithelial cells, SH-SY5Y nerve sarcoma cells or smooth muscle cells that silencing of STIM1 gene could dominantly eliminate SOCE.32,33 Our previous study indicated that STIM1 was quantitatively more important than STIM2 in activation of SOCCs in distal PASMCs.34 Besides mediating SOCE, STIM1 also contributes to store-independent Ca2+ entry, more specifically the activation of arachidonic ARC-selective channels.35,36 ARC channels have very similar biophysical characteristics to SOCCs, have been shown to contribute to receptor-operated Ca2+ entry, and are also dependent on STIM1 for activation. However, ARC channels are dependent on a PM pool of STIM1, rather than ER/SR located STIM1.36 Moreover, unlike SOCCs, which consist of six homomeric Orai1 subunits, activated ARC channels consist of both Orai1 and Orai3 subunits. Recent investigations have revealed that STIM1 acts as a sensor of Ca2+ concentration in ER/SR and could also sense reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction, temperature variation, hypoxic stress and pH changes in the cells, indicating that STIM1 might be a stress sensor sensing a range of cellular stress condition.37–40 In our previous study, we elucidated that knockdown of STIM1 abolishes acute hypoxia (4% O2, 15 min)-induced enhancement of SOCE.34 Considering SOCE largely accounts for the elevated [Ca2+]i in PASMCs, we hypothesized that STIM1 may also have an important role in prolonged hypoxia-induced SOCE.

Therefore, in this study, we further investigated the regulation and action of Orai family and STIM1 in chronic hypoxia-induced elevation of SOCE in PASMCs.

Results

Chronic hypoxia increased expression of Orai1 and Orai2, but not Orai3 and STIM1 in distal PA

Distal PA were isolated from rats exposed to either normoxia or hypoxia (10% O2) for both mRNA and protein assessment. Results showed that hypoxia induced a 64.7±22.7% and 162.2±100.3% increase in Orai1 and Orai2 mRNA level, compared with those of their respective normoxic control, while not affecting the expression of Orai3 and STIM1 (Figures 1a–d). In protein level, chronic hypoxia led to a 125.9±62.1% and 51.1±11.5% increases in Orai1 and Orai2 expression, respectively, without affecting Orai3 and STIM1 protein expression (Figures 1e and f).

Expression of Orai and STIM1 in distal PAs from rats exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (10% O2) for 21 days. Orai1 (a), Orai2 (b), Orai3 (c) and STIM1 (d) mRNA relative to 18 s was measured by qRT-PCR. Orai1, 2, 3 and STIM1 proteins were determined by western blotting (e and f). Representative blots (e) and mean intensity (f) for Orai1, 2, 3 and STIM1 blots relative to α-actin. Bar values are mean±S.E.M. (n=5 in each group). *P<0.05 versus respective normoxic control. Brackets indicate ±S.E.

Heterozygote of HIF-1α (HIF-1 α+/−) transgenic mice exhibited abolished CH upregulation of Orai2, but not Orai1

Consider that HIF-1 acts as a master regulator in hypoxic PASMCs, we further determined whether CH upregulation of Orai1 and Orai2 is HIF-1α-dependent. As described before,41 HIF-1α heterozygous transgenic mice (HIF-1 α+/−) and their littermate were subjected to either normoxic or chronic hypoxic exposure for establishment of CHPH mice model. First, in the distal PAs isolated from wild-type HIF-1 α+/+ mice, CH (10% O2, 21 days) increased Orai1 and Orai2 by 144.7±18.1% and 250.2±105.9% in mRNA levels, and 101.6±8.8% and 35.2±7.8% in protein levels, comparing with their respective normoxic controls (Figure 2). Then, in the distal PAs isolated from HIF-1 α+/− mice, the expression of Orai2 on mRNA and protein levels were decreased by 64.5±9.9% and 38.5±11.9%, respectively, compared with those of HIF-1 α+/+mice.

Knockdown of HIF-1α abolished the chronic hypoxia-upregulated Orai2 expression, while not affecting the upregulation of Orai1 in distal PAs of transgenic mice. HIF-1 α+/+ and HIF-1 α+/− mice were subjected to chronic hypoxia (10% O2, 21 days) or normoxia. Orai1 (a) and Orai2 (b) mRNA relative to 18 s was measured by qRT-PCR. Orai1 and Orai2 proteins were determined by western blotting (c, d and e). Representative blots (c) and mean intensity (d and e) for Orai1 and Orai2 blots relative to α-actin. Bar values are mean±S.E.M. (n=5 in each group). *P<0.05 versus respective normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus respective HIF-1 α+/+ control. Brackets indicate ±S.E.

Knockdown of HIF-1α by small interference RNA transfection abolished the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2, but not Orai1 in PASMCs

Besides the HIF-1α transgenic mice, we also used specific small interference RNA (siRNA) against HIF-1α (siHIF-1α) to evaluate the role of HIF-1α in hypoxic upregulation of Orai1 and Orai2 in cultured PASMCs. First, the expression of HIF-1α protein was decreased by 71.7±7.7% from hypoxic exposed PASMCs treated with siHIF-1α, compared with that of the hypoxic non-targeted siRNA (siNT) control, indicating effective knockdown. Then, in hypoxic PASMCs, knockdown of HIF-1α largely abolished the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2, while not affecting the hypoxic upregulation of Orai1 (Figure 3). In combination, these results demonstrated that the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2, but not Orai1, is HIF-1α-dependent.

Knockdown of HIF-1α using siRNA transfection abolished the chronic hypoxia upregulated Orai2 expression, while not affecting the upregulation of Orai1 in rat distal PASMCs. Six hours after transfected with non-targeting (siNT) or siRNA targeting HIF-1α (siHIF-1α), PASMCs were treated with prolonged hypoxia (4% O2, 60 h). (a) Expression of Orai1 mRNA relative to 18 s mRNA measured by qRT-PCR. (b) Western blot showing expression of Orai2 and HIF-1α proteins in PASMCs. (c and d) Mean ratios of HIF-1α and Orai2 proteins relative to α-actin protein measured by western blotting in PASMCs. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 in each group). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. Brackets indicate ±S.E.

Knockdown of Orai1 significantly reversed the hypoxic elevation of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE

PASMCs were transfected with either siNT or Orai1-specific siRNA (siOrai1) and then subjected to exposure of prolonged hypoxia (4% O2, 60 h). Compared with that of the siNT control, the knockdown efficiency of Orai1 was 76.1±2.2% and 54.2±2.9% at mRNA and protein levels, respectively (Figures 4a–c). Meanwhile, the expression of Orai2 or Orai3 was not affected by Orai1 knockdown (Figures 4a–c), suggesting specific knockdown. First, compared with that of the normoxic control, prolonged hypoxia induced a significant increase in both basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE (Figures 4d–h). Then, knockdown of Orai1 significantly attenuated the hypoxia-enhanced basal [Ca2+]i by 17.7±4.2% (Figure 4e), and the hypoxia-elevated SOCE, reflected by both calcium restoration and Mn2+ quenching. On one hand, calcium restoration experiment revealed that compared with the normoxic control, prolonged hypoxia induced a 11.8±3.6% increase in PASMCs. Knockdown of Orai1 significantly attenuated hypoxia-induced SOCE by 77.1±4.4% (Figures 4d and f). Interestingly, treatment of siOrai1 could also decrease SOCE by 60.9±2.5% in normoxic PASMCs. On the other hand, the Mn2+ quenching experiment represented similar results. Prolonged hypoxia increased SOCE to 56.5±0.9% compared to that of 33.7±12.3% in normoxic PASMCs, while knockdown of Orai1 significantly decreased the hypoxia-enhanced SOCE to 39.7±1.3% (Figures 4g and h). Different with the calcium restoration experiment, knockdown of Orai1 did not affect the rate of quenching in normoxic PASMCs. The rate of quenching was 34.1±3.6% in normoxic PASMCs treated with siOrai1 versus 33.7±12.3% in normoxic control (Figure 4h).

Knockdown of Orai1 inhibited chronic hypoxia-induced increases of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE in rat distal PASMCs. (a) Expression of Orai1, 2, 3 mRNA relative to 18 s mRNA measured by qRT-PCR in non-targeted small interfering RNA (siNT)- or siRNA targeted to Orai1 (siOrai1)-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (b) Western blot showing expression of Orai1, 2, 3 and β-actin protein in PASMCs treated with siNT or siOrai1. (c) Mean ratios of Orai1, 2 and 3 proteins relative to β-actin protein measured by western blotting in siNT- and siOrai1-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (d) Representative traces of different treatments on the time course of F340/F380 before and after restoration of extracellular Ca2+ in distal PASMCs perfused with Ca2+-free KRB solution containing 10 μM CPA, 0.5 mM EGTA and 5 μM nifedipine. (e) The effect of Orai1 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of basal [Ca2+]i in PASMCs. Basal [Ca2+]i is determined as the average F340/F380 level during 0–5 min perfusion. *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (f) The effect of Orai1 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of SOCE in PASMCs. SOCE is determined as the peak increase of F340/F380 level following calcium restoration between 15 and 30 min perfusion. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 74–116 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (g) SOCE is determined by measuring the time course of fura-2 fluorescence intensity excited at 360 nm before and after adding 200 μM Mn2+ in Ca2+-free KRB solution containing 10 μM CPA and 5 μM nifedipine in PASMCs. Data at each time point were normalized to fluorescence at time 0 (F/F0). (h) Average quenching of fura-2 fluorescence by Mn2+. Data are expressed as the percentage decrease in fluorescence at time 10 min from time 0. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 88–109 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus Hypoxic siNT control. Brackets indicate ±S.E.

Knockdown of STIM1 significantly reversed the hypoxic elevation of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE

In addition to Orai1, we also determined the role of STIM1 in the dysregulated intracellular calcium homeostasis in hypoxic PASMCs. Cells were transfected with either siNT or STIM1-specific siRNA (siSTIM1) and then subjected to exposure of prolonged hypoxia (4% O2, 60 h). Compared to that of the siNT control, the knockdown efficiency of STIM1 was 83.5±2.1% and 77.4±16.4% at mRNA and protein levels, respectively (Figures 5a–c). First, compared with that of the normoxic control, prolonged hypoxia induced a significant increase in both basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE (Figures 5d–h). Then, knockdown of STIM1 significantly attenuated the hypoxia-enhanced basal [Ca2+]i by 15.2±5.8% (Figure 5e), and the hypoxia-elevated SOCE, reflected by both calcium restoration and Mn2+ quenching. On the one hand, calcium restoration experiment revealed that compared to the normoxic control, prolonged hypoxia induced a 64.1±9.5% increase in PASMCs. Knockdown of STIM1 significantly attenuated the hypoxia-enhanced SOCE by 78.5±2.9% (Figures 5d and f). Similar to Orai1, treatment of siSTIM1 could also decrease SOCE by 37.3±9.5% in normoxic PASMCs. On the other hand, the Mn2+ quenching experiment represented similar results. Prolonged hypoxia increased SOCE to 50.9±6.9%, compared to that of 32.0±9.3% in normoxic PASMCs, while knockdown of Orai1 significantly decreased the hypoxia-enhanced SOCE to 32.0±9.3% (Figures 5g and h). In addition, knockdown of STIM1 did not affect the rate of quenching in normoxic PASMCs (Figure 5h).

Knockdown of STIM1 inhibited chronic hypoxia-induced increases of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE in rat distal PASMCs. (a) expression of STIM1 mRNA relative to 18 s mRNA measured by qRT-PCR in non-targeted small interfering RNA (siNT)- or siRNA targeted to STIM1 (siSTIM1)-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (b) Western blot showing expression of STIM1 and β-actin protein in PASMCs treated with siNT or siSTIM1. (c) mean ratios of STIM1 protein relative to β-actin protein measured by Western blotting in siNT- and siSTIM1-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (d) Representative traces of different treatments on the time course of F340/F380 before and after restoration of extracellular Ca2+ in distal PASMCs perfused with Ca2+-free KRB solution containing 10 μM CPA, 0.5 mM EGTA and 5 μM nifedipine. (e) The effect of STIM1 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of basal [Ca2+]i in PASMCs. Basal [Ca2+]i is determined as the average F340/F380 level during 0–5 min perfusion. *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (f) The effect of STIM1 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of SOCE in PASMCs. SOCE is determined as the peak increase of F340/F380 level following calcium restoration between 15 and 30 min perfusion. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 87–133 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (g) SOCE is determined by measuring the time course of fura-2 fluorescence intensity excited at 360 nm before and after adding 200 μM Mn2+ in Ca2+-free KRB solution containing 10 μM CPA and 5 μM nifedipine in PASMCs. Data at each time point were normalized to fluorescence at time 0 (F/F0). (h) Average quenching of fura-2 fluorescence by Mn2+. Data are expressed as the percentage decrease in fluorescence at time 10 min from time 0. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 90–117 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. Brackets indicate ±S.E.

Knockdown of either Orai2 or Orai3 markedly inhibited the hypoxic elevation of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE

Because both Orai1 and STIM1 largely contributed to SOCE in PASMCs, we then evaluated whether the other two Orai homologs, Orai2 and Orai3, also have important roles during the regulation of SOCE in PASMCs. Therefore, cultured PASMCs were transfected with either siNT, Orai2-specific siRNA (siOrai2) or Orai3-specific siRNA (siOrai3), and then subjected to exposure of prolonged hypoxia (4% O2, 60 h). Compared with that of the siNT control, the knockdown efficiency of was 86.7±3.8% (mRNA) and 54.5±1.2% (protein) for Orai2, and 81.0±1.4% (mRNA) and 58.6±10.0% (protein) for Orai3 (Figures 6a–c and 7a–c). First, compared with that of the normoxic control, prolonged hypoxia induced a significant increase in both basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE (Figures 6d–h and 7d–h). Then, in parallel with that happened in knockdown of Orai1, knockdown of Orai2 or Orai3 also significantly attenuated the hypoxia-enhanced basal [Ca2+]i (Figures 6e and 7e), and the hypoxia-elevated SOCE, reflected by both calcium restoration and Mn2+ quenching (Figures 6f–h and 7f–h). These results suggested that all the three Orai homologs can contribute to the regulation of SOCE in PASMCs.

Knockdown of Orai2 inhibited chronic hypoxia-induced increases of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE in rat distal PASMCs. (a) Expression of Orai1, 2 and 3 mRNA relative to 18 s mRNA measured by qRT-PCR in non-targeted small interfering RNA (siNT)- or siRNA targeted to Orai2 (siOrai2)-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (b) Western blot showing expression of Orai1, 2, 3 and β-actin proteins in PASMCs treated with siNT or siOrai2. (c) Mean ratios of Orai1, 2 and 3 proteins relative to β-actin protein measured by western blotting in siNT- and siOrai2-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (d) Representative traces of different treatments on the time course of F340/F380 before and after restoration of extracellular Ca2+ in distal PASMCs perfused with Ca2+-free KRB solution containing 10 μM CPA, 0.5 mM EGTA and 5 μM nifedipine. (e) The effect of Orai2 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of basal [Ca2+]i in PASMCs. Basal [Ca2+]i is determined as the average F340/F380 level during 0–5 min perfusion. *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (f) The effect of Orai2 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of SOCE in PASMCs. SOCE is determined as the peak increase of F340/F380 level following calcium restoration between 15 and 30 min perfusion. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 102–115 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (g) SOCE is determined by measuring the time course of fura-2 fluorescence intensity excited at 360 nm before and after adding 200 μM Mn2+ in Ca2+-free KRB solution (0 Ca2+) containing 10 μM CPA and 5 μM nifedipine in PASMCs. Data at each time point were normalized to fluorescence at time 0 (F/F0). (h) Average quenching of fura-2 fluorescence by Mn2+. Data are expressed as the percentage decrease in fluorescence at time 10 min from time 0. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 79–132 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. Brackets indicate ±S.E.

Knockdown of Orai3 inhibited chronic hypoxia-induced increases of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE in rat distal PASMCs. (a) Expression of Orai1, 2 and 3 mRNA relative to 18 s mRNA measured by qRT-PCR in non-targeted small interfering RNA (siNT)- or siRNA targeted to Orai3 (siOrai3)-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (b) Western blot showing expression of Orai1, 2, 3 and β-actin proteins in PASMCs treated with siNT or siOrai3. (c) Mean ratios of Orai1, 2 and 3 proteins relative to β-actin protein measured by western blotting in siNT- and siOrai3-treated PASMCs. *P<0.05 versus siNT. (d) Representative traces of different treatments on the time course of F340/F380 before and after restoration of extracellular Ca2+ in distal PASMCs perfused with Ca2+-free KRB solution containing 10 μM CPA, 0.5 mM EGTA and 5 μM nifedipine. (e) The effect of Orai3 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of basal [Ca2+]i in PASMCs. Basal [Ca2+]i is determined as the average F340/F380 level during 0–5 min perfusion. *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (f) The effect of Orai3 silencing on hypoxia-induced changes of SOCE in PASMCs. SOCE is determined as the peak increase of F340/F380 level following calcium restoration between 15 and 30 min perfusion. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 98–121 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. (g) SOCE is determined by measuring the time course of fura-2 fluorescence intensity excited at 360 nm before and after adding 200 μM Mn2+ in Ca2+-free KRB solution containing 10 μM CPA and 5 μM nifedipine in PASMCs. Data at each time point were normalized to fluorescence at time 0 (F/F0). (h) Average quenching of fura-2 fluorescence by Mn2+. Data are expressed as the percentage decrease in fluorescence at time 10 min from time 0. Bar values are means±S.E.M. (n=5 experiments in 81–115 cells). *P<0.05 versus normoxic control. #P<0.05 versus hypoxic siNT control. Brackets indicate ±S.E.

Discussion

As is well known, during the PH development, the hypoxic elevation of [Ca2+]i due to enhanced SOCE has a key element in promoting the pulmonary vasoconstriction and proliferation, together acting as primary vessel pathology feature underlying the pathogenesis of PH. According to our previous studies, we have proved the hypoxic upregulation of either the SOCC core components (such as TRPC1 and TRPC6)41 or the important SOCC-regulated proteins (such as caveolin-1),42 all contributed to the hypoxic-triggered SOCE in PASMCs. However, whether the other SOCE-related proteins STIM1 and Orais also contribute to this process remains unknown. Therefore, in this study, by using comprehensive knockdown of STIM1 or Orais, our results suggested that knockdown of either Orai1, Orai2, Orai3 or STIM1 could significantly reverse prolonged hypoxia-induced increases of SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i in cultured rat distal PASMCs.

Consistent with the previous studies, we discovered that hypoxic exposure significantly upregulated the expression of HIF-1α protein both in PAs and PASMCs. Moreover, hypoxia induced a significant upregulation of Orai1 and Orai2 at both mRNA and protein levels, but not Orai3. To determine whether the hypoxic-upregulated Orai1 and Orai2 depend on HIF-1α, we included both the HIF-1 α+/− transgenic mice as in vivo model and specific HIF-1α siRNA knockdown in cultured PASMCs as in vitro model. Our data showed that loss of HIF-1α by using either heterozygous HIF-1α mice or siRNA knockdown markedly abolished the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2, but not Orai1, suggesting only the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2 is HIF-1α-dependent, whereas the hypoxic upregulation of Orai1 is dependent on other mechanism. We further determine whether Orai2 has a role in the regulation of SOCE. After knockdown Orai2, we found that downregulation of Orai2 significantly attenuated the hypoxia-increased SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i in cultured rat distal PASMCs. These results suggest that the hypoxic upregulation of Orai2 contributes to the elevation of SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i via stabilizing the expression of HIF-1α, whereas the hypoxia-elevated pathway of Orai1 expression is independent of HIF-1α. In view of the key role of HIF-1α in the development of CHPH, the Orai2 may be considered a potential target retarding pulmonary vasoconstriction and proliferation. In addition, much work have been done in evaluating the role of Orai1 in the regulation of SOCE. Similar to Orai2, downregulation of Orai1 reversed the increase of SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i caused by CH, suggesting hypoxia-elevated Orai1 enhance SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i. But the transcriptional upregulation mechanisms for Orai1 were not evaluated clearly, what we do is at a beginning of this pathway so that further study need to be developed next. Unlike Orai1 and Orai2, we did not observe an upregulation of Orai3 expression upon hypoxic exposure, while knockdown of Orai3 could also significantly reversed the hypoxic elevation of SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i in rat distal PASMCs, suggesting the basal level of Orai3 is also essential for the elevation of SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i. Notably, we also observed that after knockdown of Orai3, the expression of Orai1 was decreased by ~30% (Figures 7a–c). As we know, Orai3 was reported to be an important component of ARC entry.43 Shuttleworth et al.44 reported that STIM1 is required for ARC channel activation and that both Orai1 and Orai3 contribute subunits to ARC channels. Using various preassembled concatenated Orai1–Orai3 multimers, Shuttleworth group further reported that the molecular architecture of ARC channels is a pentameric assembly of three Orai1 and two Orai3 subunits. Moreover, Charlotte Dubois et al.45 demonstrated in vitro models that enhanced Orai3 expression favors heteromerization with Orai1 to form a novel channel to support store-independent Ca2+ entry. Thus, one possible explanation is that as Orai3 could not form SOCCs by its own, knockdown of Orai3 might cause a proportion of Orai1 that could not combine with Orai3 to form CRAC or ARC channels, thus entered a pathway of protein degradation. Therefore, the loss of hypoxia-enhanced SOCE could be explained by the loss of Orai1. Regarding this point, additional studies need to be conducted in the near future to uncover the detail mechanisms about whether Orai3 has a direct impact on the decrease of basal [Ca2+]i and SOCE.

In the previous study, Ng et al.46,47 found that Orai1 and STIM1, as well as TRPC1, can form molecular complex to mediate SOCE in mouse PASMCs, suggesting a central role of STIM1 in SOCE. Hou et al.48 found that CH upregulated the expression of STIM1 both on mRNA and protein levels in rat distal PA. That is contradictory to the findings of our present study. In the present study, we found that whether at mRNA level or at protein level, CH failed to alter the expression of STIM1. Hou et al.48 found that knockdown of STIM1 using STIM1-specific siRNA reversed the enhancement of SOCE in rat PASMCs exposed to prolonged hypoxia. This finding is consistent with the results of our present study. But the PASMCs used by Hou et al. were passaged for 3–8 times, while our cells were primary cultured. We believe that the characteristics of PASMCs may vary through the process. Moreover, we used Mn2+ quenching method to assess SOCE, which is also different of the study conducted by Hou et al. As is known to all, Mn2+ quenching is the gold standard of SOCE assessment, for it can eliminate the effect of ER/SR releasing Ca2+ to the cytoplasma, thus reflecting the Ca2+ influx from the extracellular. In our present study, we found that knockdown of STIM1 reversed CH-increased basal [Ca2+]i in rat distal PASMCs, and the effect of STIM1 silencing on CH-enhanced SOCE was verified by Mn2+ quenching method. Together, we found that knockdown of STIM1 attenuated SOCE in hypoxic PASMCs, suggesting a triggering role of STIM1 in initialing SOCE upon intracellular calcium store depletion.

An outline was shown in Figure 8. In summary, in this study, we found the following: (1) chronic hypoxic exposure stabilized the expression of HIF-1α, leading to upregulation of Orai2 and a subsequent enhancement of SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i, whereas hypoxia upregulates the expression of Orai1 in a HIF-1α-independent manner; and (2) knockdown of either STIM1 or Orai family proteins (Orai1, Orai2 and Orai3) could attenuate the hypoxia-elevated SOCE and basal [Ca2+]i in PASMCs. As elevation of basal [Ca2+]i leads to contraction, proliferation and migration of PASMCs, eventually the pathogenesis of CHPH, blockage of the elevation of basal [Ca2+]i would reverse the process and prevent the genesis of CHPH. Our results added knowledge that the Orais and STIM1 could act as novel therapeutic targets for the treatment against CHPH.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangzhou Medical University. Sprague–Dawley rats (male, 175–300 g) were purchased from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (Guangzhou, China). HIF-1α heterozygous-mutant (HIF-1α+/–) mice were genotyped as described before.49 All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities. Littermate mice from HIF-1α+/+×HIF-1α+/– mating were genotyped at 3–4 weeks old.

Exposure of animals to chronic hypoxia

Rats (male, 175–300 g) or mice (male, 8 weeks old) were placed in a hypoxia chamber for 21 days to establish the chronic hypoxia-induced PH animal model, as previously described.50 The chamber was continuously flushed with a mixture of room air and N2 to maintain 10±0.5% O2 and CO2<0.5%. The chamber O2 concentration was continuously monitored using a PRO-OX unit (RCI Hudson, Anaheim, CA, USA). Animals were exposed to room air for 10 min twice a week for changing cage and replenishing food and water. Normoxic control animals were kept in room air next to the hypoxic chamber.

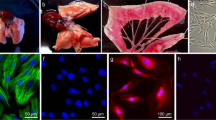

Isolation of distal PA and culture of PASMCs

The distal intrapulmonary arteries (⩾fourth generation) were dissected from normoxic or chronic hypoxic rats and mice, as we previously described.51 PASMCs were enzymatically isolated and plated onto 25 mm glass coverslips (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).52 Rat PASMCs were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 1 g/l D-glucose (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) until 60–70% confluence prior each experiment.

siRNA transfection and prolonged hypoxic exposure of PASMCs

siRNAs targeting to rat HIF-1α (siHIF-1α), Orai1 (siOrai1), Orai2 (siOrai2), Orai3 (siOrai3), STIM1 (siSTIM1) and siNT used as negative control were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Suzhou, China). Rat PASMCs were transfected with 50 nM siHIF-1α, siOrai1, siOrai3, siSTIM1, siNT or 100 nM siOrai2 using HiPerFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen,Valencia, CA, USA) at 6 μl/ml as transfection vehicle in 0 serum DMEM. After 6 h transfection, serum was added to a final concentration of 0.3% and PASMCs were exposed to normoxia or hypoxia (4% O2) for 60 h. Knockdown efficiency was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and western blotting.

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ concentration

After incubation with 7.5 μM fura-2 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 60 min at 37 °C under an atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air, coverslips with PASMCs were mounted in a closed polycarbonate chamber clamped in a heated aluminum platform (PH-2; Warner Instrument, Hamden, CT, USA) on the stage of a Nikon TSE 100 Ellipse inverted microscope (Melville, NY, USA). The chamber was perfused at 1 ml/min with Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) solution, which contained (in mM) 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 0.57 MgSO4, 1.18 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2 and 10 glucose. To assess SOCE, we perfused PASMCs for at least 10 min with Ca2+-free KRB containing 5 μM nifedipine to prevent calcium entry through L-type VDCCs and 10 μM CPA to deplete SR calcium stores. KRB perfusate also contained 0.5 mM EGTA to chelate any residual Ca2+. SOCE was assessed in two ways. First, we measured [Ca2+]i at 12 s intervals before and after restoration of extracellular [Ca2+] to 2.5 mM. SOCE was evaluated from the increase in [Ca2+]i caused by restoration of extracellular [Ca2+] in the continued presence of cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and nifedipine. Second, we monitored fura-2 fluorescence excited at 360 nm at 30 s intervals before and after addition of MnCl2 (200 μM) to the cell perfusate. SOCE was evaluated from the rate at which fura-2 fluorescence was quenched by Mn2+, which enters the cell as a Ca2+ surrogate and reduces fura-2 fluorescence on binding to the dye. Fluorescence excited at 360 nm is the same for Ca2+-bound and Ca2+-free fura-2; therefore, changes in fluorescence can be assumed to be caused by Mn2+ alone. Quenching was quantified as the change in F360 (ΔF360) measured from 5 to 15 min and expressed as a percentage of F360 at 5 min.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA in de-endothelialized distal PA and PASMCs was extracted using TRIzol method.34 Reverse transcription was performed using PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara, Japan). The reaction mixture contained 1 μg total RNA in a 20 μl volume. cDNA was quantified by qRT-PCR using QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) in a iCycler IQ real-time PCR detection system (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the following conditions: 95 °C for 15 min and 45 cycles, each at 94 °C for 15 s, 57.5 °C for 20 s and 72 °C for 20 s. The volume of each qRT-PCR reaction mixture was 25 μl containing 300 nM forward and reverse primers and cDNA template from 50 ng RNA. Primer sequences of rat Orai1, Orai2, Orai3, STIM1 and 18 s were designed using Primer3 software (http://simgene.com/Primer3), and are shown as follows, where S is sense and AS is antisense:

Orai1-S (5′- GATGAGCCTCAACGAGCACT-3′),

Orai1-AS (5′- GACTTCCACCATCGCTACCA-3′),

Orai2-S (5′- GTGGGTCTCATCTTCGTGGT-3′),

Orai2-AS (5′- CCACCTGTAGGCTTCTCTCG-3′),

Orai3-S (5′- GCCCAGCTTTAGACTGTTGC-3′),

Orai3-AS (5′- CTGAGCAGGAATTTGGCTTC-3′),

STIM1-S (5′- ATGCCAATGGTGATGTGGAT-3′),

STIM1-AS (5′- CCATGGAAGGTGCTGTGTTT-3′),

18s-S (5′- GCAATTATTCCCCATGAACG-3′),

18s-AS (5′- GGCCTCACTAAACCATCCAA-3′).

Identity of the qPCR products was confirmed by (1) a single sharp peak in the melting curve performed after cDNA amplification, (2) a single band of the expected size resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and (3) DNA sequencing. Melting curves were performed at 95 °C for 1 min and 55 °C for 1 min, followed by 80 increments of 0.5 °C at 10 s intervals. qRT-PCR detection threshold cycle (CT) values were generated by iCycler IQ software. Relative concentration of each transcript was calculated using the Pfaffl method.53 Efficiency for each gene was determined from five-point serial dilutions of positive control cDNA samples.

Western blotting

Total proteins in tissues or cells were extracted in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Biocolors, Shanghai, China) containing 1% NP40, 0.1% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 1% 100 mM PMSF. De-endothelialized distal PA was homogenized using ultrasonication. PASMCs were washed with phosphate buffered saline and homogenized by scraping in lysis buffer on ice and then were span down to remove cell debris. Total protein concentration in homogenate samples were determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Samples were combined with 5× loading buffer, boiled and resolved on SDS-PAGE calibrated with prestained protein molecular weight markers. Separated proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (pore size 0.2 μM; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-0.1% Tween-20, membranes were blotted with mouse monoclonal antibody for HIF-1α (Clone H1a67; Novus Biologicals Inc., Littleton, CO, USA), α-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), rabbit polyclonal antibodies for Orai1, Orai2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Orai3 (Prosci, Poway, CA, USA), or rabbit monoclonal antibodies for STIM1 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The membranes were then washed and probed with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (KPL, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The bound antibodies were detected using an enhanced luminol-linked chemiluminescence detection system (ECL, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Reagents and drugs

Unless otherwise specified, all reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions (30 mM) of CPA and nifedipine were made in pluronic dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Invitrogen). Fura-2 AM (Invitrogen) was prepared on the day of the experiment as a 2.5 mM stock solution in DMSO.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Student’s t-test for two groups and one-way ANOVA for multiple groups of data. Differences were considered significant when P< 0.05. Data are presented as means±S.E.M.; ‘n’ refers to the sample size (that is, the number of the animals providing PAs or primary culture of PASMCs).

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Simonneau G, Gatzoulis MA, Adatia I, Celermajer D, Denton C, Ghofrani A et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62 (25 Suppl): D34–D41.

Golovina VA, Platoshyn O, Bailey CL, Wang J, Limsuwan A, Sweeney M et al. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca(2+) entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2001; 280: H746–H755.

Brough GH, Wu S, Cioffi D, Moore TM, Li M, Dean N et al. Contribution of endogenously expressed Trp1 to a Ca2+-selective, store-operated Ca2+ entry pathway. FASEB J 2001; 15: 1727–1738.

Jiang Q, Lu W, Yang K, Hadadi C, Fu X, Chen Y et al. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate inhibits hypoxia-induced enhancement of SOCE in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells via the PKG-PPAR-gamma signaling axis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2016; 311: C136–C149.

Smyth JT, Dehaven WI, Jones BF, Mercer JC, Trebak M, Vazquez G et al. Emerging perspectives in store-operated Ca2+ entry: roles of Orai, Stim and TRP. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1763: 1147–1160.

Liao Y, Erxleben C, Yildirim E, Abramowitz J, Armstrong DL, Birnbaumer L . Orai proteins interact with TRPC channels and confer responsiveness to store depletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 4682–4687.

Peel SE, Liu B, Hall IP . ORAI and store-operated calcium influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008; 38: 744–749.

Lai N, Lu W, Wang J . Ca(2+) and ion channels in hypoxia-mediated pulmonary hypertension. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8: 1081–1092.

Varnai P, Hunyady L, Balla T . STIM and Orai: the long-awaited constituents of store-operated calcium entry. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2009; 30: 118–128.

Berra-Romani R, Mazzocco-Spezzia A, Pulina MV, Golovina VA . Ca2+ handling is altered when arterial myocytes progress from a contractile to a proliferative phenotype in culture. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2008; 295: C779–C790.

Demuro A, Penna A, Safrina O, Yeromin AV, Amcheslavsky A, Cahalan MD et al. Subunit stoichiometry of human Orai1 and Orai3 channels in closed and open states. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 17832–17837.

Derler I, Madl J, Schutz G, Romanin C . Structure, regulation and biophysics of I(CRAC), STIM/Orai1. Adv Exp Med Biol 2012; 740: 383–410.

Lee KP, Yuan JP, Hong JH, So I, Worley PF, Muallem S . An endoplasmic reticulum/plasma membrane junction: STIM1/Orai1/TRPCs. FEBS Lett 2010; 584: 2022–2027.

Liao Y, Erxleben C, Abramowitz J, Flockerzi V, Zhu MX, Armstrong DL et al. Functional interactions among Orai1, TRPCs, and STIM1 suggest a STIM-regulated heteromeric Orai/TRPC model for SOCE/Icrac channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 2895–2900.

Madl J, Weghuber J, Fritsch R, Derler I, Fahrner M, Frischauf I et al. Resting state Orai1 diffuses as homotetramer in the plasma membrane of live mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 41135–41142.

Soboloff J, Rothberg BS, Madesh M, Gill DL . STIM proteins: dynamic calcium signal transducers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13: 549–565.

Mercer JC, Dehaven WI, Smyth JT, Wedel B, Boyles RR, Bird GS et al. Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 24979–24990.

DeHaven WI, Smyth JT, Boyles RR, Putney JJ . Calcium inhibition and calcium potentiation of Orai1, Orai2, and Orai3 calcium release-activated calcium channels. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 17548–17556.

Lis A, Peinelt C, Beck A, Parvez S, Monteilh-Zoller M, Fleig A et al. CRACM1, CRACM2, and CRACM3 are store-operated Ca2+ channels with distinct functional properties. Curr Biol 2007; 17: 794–800.

Hoth M, Penner R . Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature 1992; 355: 353–356.

Hoth M, Penner R . Calcium release-activated calcium current in rat mast cells. J Physiol 1993; 465: 359–386.

Cai X . Molecular evolution and structural analysis of the Ca(2+) release-activated Ca(2+) channel subunit, Orai. J Mol Biol 2007; 368: 1284–1291.

Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Feske S, Cruz-Guilloty F, Oh-hora M, Neems DS et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of Orai proteins. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 16232–16243.

Hou X, Pedi L, Diver MM, Long SB . Crystal structure of the calcium release-activated calcium channel Orai. Science 2012; 338: 1308–1313.

Mignen O, Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ . Both Orai1 and Orai3 are essential components of the arachidonate-regulated Ca2+-selective (ARC) channels. J Physiol 2008; 586: 185–195.

Liou J, Kim ML, Heo WD, Jones JT, Myers JW, Ferrell JJ et al. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr Biol 2005; 15: 1235–1241.

Manji SS, Parker NJ, Williams RT, van Stekelenburg L, Pearson RB, Dziadek M et al. STIM1: a novel phosphoprotein located at the cell surface. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000; 1481: 147–155.

Roos J, DiGregorio PJ, Yeromin AV, Ohlsen K, Lioudyno M, Zhang S et al. STIM1, an essential and conserved component of store-operated Ca2+ channel function. J Cell Biol 2005; 169: 435–445.

Oh-hora M, Rao A . Calcium signaling in lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol 2008; 20: 250–258.

Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B et al. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 2006; 441: 179–185.

Wu MM, Buchanan J, Luik RM, Lewis RS . Ca2+ store depletion causes STIM1 to accumulate in ER regions closely associated with the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol 2006; 174: 803–813.

Wang Y, Deng X, Hewavitharana T, Soboloff J, Gill DL . Stim, ORAI and TRPC channels in the control of calcium entry signals in smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2008; 35: 1127–1133.

Putney JJ . Capacitative calcium entry: sensing the calcium stores. J Cell Biol 2005; 169: 381–382.

Lu W, Wang J, Peng G, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT . Knockdown of stromal interaction molecule 1 attenuates store-operated Ca2+ entry and Ca2+ responses to acute hypoxia in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2009; 297: L17–L25.

Shuttleworth TJ . STIM and Orai proteins and the non-capacitative ARC channels. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012; 17: 847–860.

Thompson JL, Shuttleworth TJ . A plasma membrane-targeted cytosolic domain of STIM1 selectively activates ARC channels, an arachidonate-regulated store-independent Orai channel. Channels (Austin) 2012; 6: 370–378.

Hawkins BJ, Irrinki KM, Mallilankaraman K, Lien YC, Wang Y, Bhanumathy CD et al. S-glutathionylation activates STIM1 and alters mitochondrial homeostasis. J Cell Biol 2010; 190: 391–405.

Xiao B, Coste B, Mathur J, Patapoutian A . Temperature-dependent STIM1 activation induces Ca(2)+ influx and modulates gene expression. Nat Chem Biol 2011; 7: 351–358.

Ritchie MF, Samakai E, Soboloff J . STIM1 is required for attenuation of PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance during T-cell activation. EMBO J 2012; 31: 1123–1133.

Ottolia M, John S, Xie Y, Ren X, Philipson KD . Shedding light on the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1099: 78–85.

Wang J, Weigand L, Lu W, Sylvester JT, Semenza GL, Shimoda LA . Hypoxia inducible factor 1 mediates hypoxia-induced TRPC expression and elevated intracellular Ca2+ in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 2006; 98: 1528–1537.

Yang K, Lu W, Jiang Q, Yun X, Zhao M, Jiang H et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-mediated inhibition on hypoxia-triggered store-operated calcium entry. A caveolin-1-dependent mechanism. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2015; 53: 882–892.

Gonzalez-Cobos JC, Zhang X, Zhang W, Ruhle B, Motiani RK, Schindl R et al. Store-independent Orai1/3 channels activated by intracrine leukotriene C4: role in neointimal hyperplasia. Circ Res 2013; 112: 1013–1025.

Shuttleworth TJ . Arachidonic acid, ARC channels, and Orai proteins. Cell Calcium 2009; 45: 602–610.

Dubois C, Vanden AF, Lehen'Kyi V, Gkika D, Guarmit B, Lepage G et al. Remodeling of channel-forming ORAI proteins determines an oncogenic switch in prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 2014; 26: 19–32.

Ng LC, Ramduny D, Airey JA, Singer CA, Keller PS, Shen XM et al. Orai1 interacts with STIM1 and mediates capacitative Ca2+ entry in mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010; 299: C1079–C1090.

Ng LC, McCormack MD, Airey JA, Singer CA, Keller PS, Shen XM et al. TRPC1 and STIM1 mediate capacitative Ca2+ entry in mouse pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 2009; 587 (Pt 11): 2429–2442.

Hou X, Chen J, Luo Y, Liu F, Xu G, Gao Y . Silencing of STIM1 attenuates hypoxia-induced PASMCs proliferation via inhibition of the SOC/Ca2+/NFAT pathway. Respir Res 2013; 14: 2.

Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev 1998; 12: 149–162.

Yu AY, Shimoda LA, Iyer NV, Huso DL, Sun X, McWilliams R et al. Impaired physiological responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J Clin Invest 1999; 103: 691–696.

Lu W, Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT . Differences in STIM1 and TRPC expression in proximal and distal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle are associated with differences in Ca2+ responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008; 295: L104–L113.

Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT . Capacitative calcium entry and TRPC channel proteins are expressed in rat distal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004; 286: L848–L858.

Pfaffl MW . A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res 2001; 29: e45.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81170052, 81520108001, 81630004, 81470246 and 81220108001), Guangzhou Department of Education (13C08 and 12A001S), Guangzhou Science and Technology Programme Projects (201607020030), and Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Xu, C., Zheng, Q. et al. Orai1, 2, 3 and STIM1 promote store-operated calcium entry in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Cell Death Discov. 3, 17074 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.74

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddiscovery.2017.74

This article is cited by

-

Nupr1-mediated vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype transformation involved in methamphetamine induces pulmonary hypertension

Cell Biology and Toxicology (2024)

-

SARS-CoV-2 spike protein receptor-binding domain perturbates intracellular calcium homeostasis and impairs pulmonary vascular endothelial cells

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2023)

-

Role of store-operated Ca2+ entry in cardiovascular disease

Cell Communication and Signaling (2022)