Abstract

Infantile hemangioma is a vascular tumor that exhibits a unique natural cycle of rapid growth followed by involution. Previously, we have shown that hemangiomas arise from CD133+ stem cells that differentiate into endothelial cells when implanted in immunodeficient mice. The same clonally expanded stem cells also produced adipocytes, thus recapitulating the involuting phase of hemangioma. In the present study, we have elucidated the intrinsic mechanisms of adipocyte differentiation using hemangioma-derived stem cells (hemSCs). We found that platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) is elevated during the proliferating phase and may inhibit adipocyte differentiation. hemSCs expressed high levels of PDGF-B and showed sustained tyrosine phosphorylation of PDGF receptors under basal (unstimulated) conditions. Inhibition of PDGF receptor signaling caused enhanced adipogenesis in hemSCs. Furthermore, exposure of hemSCs to exogenous PDGF-BB reduced the fat content and the expression of adipocyte-specific transcription factors. We also show that these autogenous inhibitory effects are mediated by PDGF receptor-β signaling. In summary, this study identifies PDGF signaling as an intrinsic negative regulator of hemangioma involution and highlights the therapeutic potential of disrupting PDGF signaling for the treatment of hemangiomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Infantile hemangioma is the most common tumor of infancy.1 This vascular lesion appears in 4–10% of newborns, and is especially prevalent in Caucasian infants.1, 2 Occasionally, hemangiomas cause significant morbidity through obstruction, ulceration, or compromised cardiovascular function.1, 3 Therefore, optimal clinical management of hemangiomas is still an active area of research.3 Hemangioma pathogenesis involves a predictable pattern of growth. During the first few months of the infant’s life, the tumor proliferates rapidly and reaches a maximum size.4 Then spontaneous involution over the first several years of childhood ensues. By adolescence, involution is complete, and the tumor is a fibrofatty mass bearing little resemblance to the highly vascular original.3 From a research perspective, hemangioma provides a unique model system for studying blood vessel growth and regulation and the interaction between the blood vessels and adipogenesis.

Until recently, the molecular mechanisms underlying hemangioma growth and involution have been poorly understood. Recent studies have probed the genetic and biochemical basis for the appearance and regression of this vascular tumor. In a study of familial hemangiomas, genetic linkage analysis identified platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFR-β) as a possible contributor to hemangioma heredity.5 Later, a study examining global gene expression changes between the hemangioma growth phases by microarray profiling showed a reduction in PDGFR-β expression during the involutive phase.6 Although the levels of PDGFRs are lower than placenta (a commonly used tissue for comparisons), the findings do point to a possible role for PDGF signaling in hemangioma pathogenesis.

The PDGF family of growth factors is comprised of several disulfide-bound dimers that bind tyrosine kinase receptors.7 PDGF ligands include PDGF-AA, -AB, -BB, -CC, and -DD (all comprising two joined peptide chains of A, B, C, or D; PDGF-AB is the only heterodimer reported) and exert their effects by binding to one or both of two structurally related receptors, PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β. The two receptors show overlapping but non-identical signaling functions. PDGFR-α binds to all PDGF chains except for PDGF-D and PDGFR-β binds only to the PDGF-B and PDGF-D chains. However, further complexity and/or fine-tuning can be achieved by receptor hetero-dimerization. PDGFR-αβ heterodimers may bind to PDGF-B, -C, and -D homodimers as well as the PDGF-AB heterodimer. Upon activation, a diverse range of cellular activities is altered, including cell survival and proliferation, chemotaxis, and angiogenesis.7 Not surprisingly, aberrant PDGF signaling has been implicated in a variety of pathologies, including organ fibrosis, myeloproliferative disorders, atherosclerosis, and several malignancies.7, 8

The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of PDGF signaling in the involution of infantile hemangioma. As PDGF signaling has a positive effect on the formation of vascular networks,9, 10 we hypothesize that PDGF growth factors are negative regulators of hemangioma involution. We investigated the presence of PDGF ligands and receptors in hemangioma specimens and hemangoma-derived cells. We then tested the effects of PDGF ligands on the adipogenic differentiation of hemangioma cells and identified the receptor.

Results

Decrease in PDGFR expression coincides with hemangioma involution

Our first objective was to determine whether hemangioma specimens express PDGFRs. To achieve this, we obtained proliferating hemangioma specimens and normal human skin tissues for comparisons. Our results show significantly elevated PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β in proliferating hemangiomas as compared with normal skin (Figure 1a). The involutive phase of hemangioma was associated with increased PPARγ expression (transcription factor involved in adipogenesis) and reduced levels of both PDGFRs. We next determined the localization of the PDGFRs in proliferating hemangiomas. Immunohistochemistry showed predominant PDGFR-α localization to the endothelial cells (Figure 1b). PDGFR-β, on the other hand, showed more widespread distribution, being localized to the vascular endothelial and perivascular cells, and the stroma/interstitial cells. This distribution pattern of PDGFR-β was confirmed by double-labeling with PDGFR-β antibody and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (mural cell marker) antibody (Figure 1c).

Expression of PDGF receptors in proliferating and involuting hemangiomas. (a) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of PDGFR-α, -β, and PPARγ in proliferating and involuting hemangiomas (data normalized to 18S rRNA and presented as relative to normal skin; *P<0.05 compared with normal skin, †P<0.05 compared with proliferating hemangioma; n=3). (b) Immunostaining of proliferating hemangiomas for PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β (images taken at × 20, inserts show higher magnification; brown=DAB staining, blue=hematoxylin). (c) Immunofluorescence double labeling for mesenchymal cell marker α-SMA and PDGFR-β (images taken at × 20, green=PDGFR-β, red=α-SMA)

We next determined the activity of the PDGFRs in hemangioma specimens using phospho-specific PDGFR antibodies. Immunofluorescence staining showed that both PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β are phosphorylated at tyrosine 849 and 1021, respectively (Figure 2). These phosphorylated sites in the PDGFRs are commonly used to determine the activated form of the receptors.

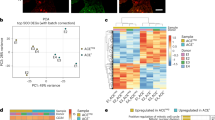

Significantly elevated levels of PDGF-B in hemangioma stem cells

We next assessed whether hemangioma-derived CD133+ stem cells express PDGF ligands and receptors in culture. As both PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β are expressed in proliferating hemangiomas (Figure 1), we examined the expression of all ligands (PDGF-A, -B, -C, and -D). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of hemangioma-derived stem cells (hemSCs) confirmed the expression of both PDGFRs. The transcript levels were not significantly different than the control bone marrow-mesenchymal progenitor cells (bm-MPCs) (Figure 3a). When we assayed for the PDGF ligands, we found significantly elevated levels of PDGF-B and downregulated expression of PDGF-A as compared with the bm-MPCs (Figure 3b). There were no significant differences in the expression of PDGF-C and PDGF-D. Using a sandwich immunoassay, we determined the production of PDGF-BB in hemSC supernatant. Our results show approximately 60 pg of PDGF-BB in hemSCs per ml media. PDGF-BB values in the bm-MPC media were closer to the lower limit of the linear range, and showed 1.4 pg/ml after overnight incubation (Figure 3c). The cell lysates also showed significantly higher PDGF-BB in hemSCs compared with bm-MPCs (Figure 3d). Next, we wanted to know whether PDGF-BB creates an autocrine loop in the hemSCs. To achieve this, we probed the hemSCs for activated PDGFRs under basal conditions (without exogenous growth factor exposure). Using phospho-PDGFR α and β immunoassays, we show that hemSCs exhibit constitutively activated PDGFRs (Figure 3e). Furthermore, treatment of hemSCs to exogenous 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB further increased the level of PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β tyrosine phosphorylation (Figure 3e). These findings suggest that the main ligand for PDGFRs in hemangioma stem cells is PDGF-BB (Figure 3f) and that an autocrine signaling loop exists.

Expression of PDGF signaling axis in hemangioma-derived CD133+ cells. (a) Expression of PDGFRs in hemSCs and bm-MPCs (data normalized to 18 S rRNA and presented as relative to bm-MPCs; two different hemSC preparations run in triplicates were averaged). (b) Expression of PDGF transcripts in hemSCs (data presented as in (a); *P<0.05 compared with bm-MPCs; right panel shows the expression of PDGF-A, PDGF-C, and PDGF-D at a lower scale). (c) PDGF-BB levels in media from cells cultured for 48 h in EBM2/20%FBS (with growth factors) (*P<0.05 compared with bm-MPCs). (d) PDGF-BB levels in cell lysates determined by ELISA (*P<0.05 compared with bm-MPCs). (e) Levels of phosphorylated PDGFR-α and -β in hemSCs with or without exogenous PDGF-BB stimulation (cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB; *P<0.05 compared with unstimulated cells). (f) Schematic illustration of the hypothesized PDGF polypeptides and the corresponding receptors on hemangioma stem cell surface

PDGF does not alter hemSC proliferation

PDGF has been shown to promote proliferation of mesenchymal cells through inducing intracellular kinase activity.11 We, therefore, tested whether high levels of PDGF may regulate hemSC mesenchymal/mesodermal phenotype and cell proliferation. We elected to supplement hemSCs with exogenous PDGF-BB for this experiment because, (1) hemSCs show elevated levels of the PDGF-B chain (Figure 3b), (2) treatment of hemSCs to exogenous PDGF-BB led to further increase in PDGFR phosphorylation, thus providing us with a robust system to assess for the PDGF-BB role, and (3) PDGF-BB has been shown to be a mitogen for connective tissue cells including smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts.12, 13 Our results show that exposure of the hemSCs to PDGF-BB did not alter cell morphology or the expression of mesenchymal markers, including α-SMA, calponin (α-SMA-associated protein), or desmin (Figure 4a). Furthermore, PDGF-BB exhibited no significant effect on hemSC migration and proliferation (Figures 4b and c).

Effect of PDGF-BB on hemSC phenotype and cellular proliferation. (a) Fluorescence immunostaining for mesenchymal markers α-SMA, calponin and desmin in hemSCs. Umbilical artery SMCs were used as control for the mural markers. Effect of exogenous PDGF-BB on hemSC migration (b) and proliferation (c) (data presented as relative to control media treated cells; n=3)

PDGF-BB inhibits adipogenesis in hemangioma-derived SCs in a dose-dependent manner

We investigated the role of PDGF on the final fate of the hemSCs: terminal differentiation into adipocytes. We have previously shown that these CD133+ hemSCs produce human adipocytes in the mouse model of hemangioma, illustrating that these cells are critical for the process of involution.14 These human adipocytes appear spontaneously in the mouse model around 56 days following cell administration (time coinciding with decreased microvessel density). To test the effect of PDGF on adipogenesis, we exposed hemSCs to adipogenic media supplemented with PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB, and PDGF-BB. Of all three dimers tested, only PDGF-BB inhibited lipid accumulation and adipogenic differentiation in the hemSCs (Figure 5a). This inhibition was associated with a marked reduction in the expression of adipogenesis-specific transcription factors, C/EBPα and PPARγ15, 16, 17 (Figure 5b). These findings demonstrate that PDGF signaling actively inhibits the induction of adipogenic transcription factors. We also examined whether exposure to the adipogenic media itself changes PDGFR expression in the hemSCs. Although a slight decrease in PDGFR-β was seen in the hemSCs exposed to the adipogenic media, it did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5c).

PDGF-BB inhibits adipogenic differentiation in hemSCs. (a) Representative oil red O staining of hemSCs cultured in adipogenic differentiation media supplemented with 10 ng/ml of PDGF-AA, -AB, or -BB. (b) Quantitative analysis of adipogenic differentiation in the presence of PDGF polypeptides was assessed by real-time RT-PCR for adipogenesis-specific transcription factors, C/EBPα and PPARγ (data normalized to 18 S rRNA and presented as relative to adipogenic media; *P<0.05 compared with the adipogenic media; n=3). (c) Effect of adipogenic differentiation on PDGFR expression in hemSCs at day 7. (d) Oil red O staining of hemSCs cultured with different growth factors (each at 10 ng/ml) illustrating specific inhibition of hemSC adipogenesis by PDGF signaling

Next, we determined whether other growth factors that regulate cell differentiation also inhibit adipogenesis in the hemSCs. We tested the effect of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A and VEGF-B (involved in hemangioma endothelial cell differentiation18, 19, 20), stem cell factor (SCF) and stromal-derived factor (SDF) (involved in mesenchymal progenitor growth21) on hemSC adipogenic differentiation. Oil red O staining revealed that only PDGF-BB inhibited adipogenesis in the hemSCs (Figure 5d). The effect of PDGF was also dose dependent, as increasing the concentration from 10 to 50 ng/ml completely abolished C/EBPα and PPARγ expression and downregulated fatty-acid-binding protein-4 (FABP-4) (Figures 6a and b). In contrast, PDGF-AA, which does not bind to the PDGFR-β, had no effect FABP-4 expression even when administered at 50 ng/ml (Figure 6c). We also examined whether a similar effect of PDGF-BB is evident in the bm-MPCs that express PDGFRs and all PDGF ligands. Analysis of early and late markers of adipogenesis showed a similar pattern to that of hemSCs, whereby PDGF-BB (50 ng/ml) inhibited C/EBPα, PPARγ, and FABP-4 (Figure 6d). Interestingly, PPARγ and FABP-4 were downregulated in the bm-MPCs but not completely normalized, as is the case for C/EBPα. This suggests that PDGF-BB may have a direct regulatory role on C/EBPα and the regulation of PPARγ is secondary.

PDGF-BB, but no other PDGF polypeptides, prevent full functional differentiation of hemSCs. (a) Oil red O staining of hemSCs cultured in low (10 ng/ml) and high (50 ng/ml) PDGF polypeptide levels. PDGF-AA and –AB were ineffective against preventing adipogenic differentiation at 10 and 50 ng/ml. (b) Quantitative analysis of early adipogenesis-specific transcription factors (C/EBPα and PPARγ) and late marker of adipocytes, FABP-4 (*P<0.05 compared to adipogenic media; n=3). (c) Expression of FABP-4 in hemSCs treated with 50 ng/ml PDGF-AA. (d) Inhibition of adipogenesis by PDGF-BB in bm-MPCs (data presented relative to adipogenic media; *P<0.05 compared with adipogenic media; n=3)

Negation of PDGFR- β activity normalizes the inhibitory effect of PDGF-BB in hemSCs

To confirm whether autogenous PDGF signaling is involved in preventing hemSCs to differentiate into adipocytes, we treated the cells with chemical inhibitors of PDGFR tyrosine kinase activity. Two inhibitors, AG-370 and AG-1296,22, 23, 24, 25 were selected based on the inhibition of PDGF signaling in cell culture studies. The cells were treated with the inhibitors for the duration of the adipogenic differentiation. Oil red O staining showed modest increases in adipocyte differentiation when hemSC were treated with PDGFR inhibitor AG-1296 but not with AG-370 (Figure 7a). Quantitative RT-PCR showed significantly elevated C/EBPα and PPARγ upon treatment of hemSCs with AG-1296 (Figure 7b). This indicated that the PDGFR tyrosine kinase activity is required for the inhibitory effect of PDGF-BB on hemSC differentiation. To gain further insight into the contribution of PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β in this signaling pathway, we used specific neutralizing antibodies26 targeting the two subunits. Our results show that only PDGFR-β neutralization upregulated both C/EBPα and PPARγ in cells exposed to adipogenic media (Figures 7a and b). No significant changes were observed with PDGFR-α neutralizing antibody. We extended this study and determined whether these inhibitors and neutralizing antibodies will also normalize the inhibitory effect of exogenous PDGF-BB. By quantitative analysis, cells cultured in the presence of PDGF-BB plus PDGF inhibitors showed higher levels of C/EBPα, PPARγ, and FABP-4 than with PDGF-BB alone (Figure 7c). As it is difficult to maintain receptor blockade using neutralizing antibodies in culture, we performed stable short hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of the individual PDGFRs. PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β shRNA plasmid transfection produced significant silencing of the receptor mRNA for approximately 30 days (corresponding to 6 subcultures) (Figures 8a and b). Contrary to what we noticed with the neutralizing antibody, downregulation of PDGFR-α reduced the inhibitory effect of exogenous PDGF-BB (Figure 8c). Almost half of the inhibitory effect of PDGF-BB was normalized with PDGFR-α knockdown only. This was not associated with altered expression of PDGFR-β (Figure 8a). Similarly, we performed knockdown of PDGFR-β and assayed the cells for the reversal of the PDGF-BB effect. Suppression of PDGFR-β almost completely reversed the effect of PDGF-BB (Figure 8c) indicating that receptor-β is the major receptor mediating the inhibitory effect of PDGF-BB (Figure 8d).

Inhibiting cell-autogenous PDGF signaling enhances adipogenesis. (a) Oil red O staining of hemSCs exposed to adipogenic media with or without PDGFR inhibitors, AG-370 and AG-1296, and PDGFR neutralizing antibodies. (b) Quantitative analysis of C/EBPα and PPARγ in cells exposed to PDGF inhibitors as in (a) (data presented relative to control media; *P<0.05 compared with control media; †P<0.05 compared with adipogenic media; n=3). (c) Effect of PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β-neutralizing antibodies and chemical inhibitors on reversing the inhibition by exogenous PDGF-BB (*P<0.05 compared with PDGF-BB treatment)

PDGF-BB employs PDGFR-β in hemSCs. shRNA-mediated knockdown of PDGFR-α (a) and PDGFR-β (b) in hemSCs at sub-passage 1 (subP1; following 2 weeks of puromycin selection) and sub-passage 6 (six serial passages after puromycin selection) (*P<0.05 compared with control shRNA). (c) shRNA-knockdown of PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β in hemSCs reduced the inhibitory effect of PDGF-BB on hemSC adipogenesis (*P<0.05 compared with control shRNA). (d) Schematic illustrating the findings of the study and our working hypothesis. High levels of PDGF-BB from hemSCs during proliferation mediate intracellular signaling through PDGFR-β (predominantly PDGFR-ββ homodimer with contribution from PDGFR-αβ heterodimer) to inhibit C/EBPα and PPARγ expression and adipogenesis (i.e., involution). Upon regression of the vessels and removal of the PDGF-BB source, adipogenesis is triggered

Discussion

This study was based on the hypothesis that specific isoforms of PDGF are involved in the involution phase of hemangioma, and that the regulation of adipogenesis is via specific receptor-mediated signaling mechanisms. Data from our study demonstrates that PDGF signaling inhibits the differentiation of the hemangioma stem cells into adipocytes. Levels of adipogenic transcription factors (C/EBPα and PPARγ) and late marker of adipogenesis (FABP-4) are increased following differentiation of both hemangioma derived SCs and bm-MPCs. Addition of PDGF-BB specifically prevented the activation of C/EBPα and PPARγ and downregulated FABP-4 expression. Furthermore, we show that this inhibitory effect of PDGF-BB is mediated by PDGFR-β.

This is the first study that has evaluated the role of PDGF signaling in hemangioma SCs. There are, however, reports of PDGF altering adipogenic differentiation in ‘pre-adipocyte’ cell lines. For example, PDGF-BB was shown to be essential in inducing adipogenesis in serum-free culture of 3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes.27, 28 This serum-free culture was devised to decipher the role of critical culture components needed for adipocytic differentiation. These studies have demonstrated induction of C/EBPα by the addition of PDGF-BB in the differentiation media. In the same cell line, PDGFR-β itself is downregulated when the cells are treated with differentiation media.29 In human primary pre-adipocyte cultures (isolated from sub-cutaneous biopsy specimens), PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB were shown to be ineffective in inducing or inhibiting PPARγ and glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (expressed by adipocytes30).31 However, both PDGF-AA and PDGF-BB increased cell proliferation. These findings are in contrast to what we see in the hemSCs and even bm-MPCs. We show that PDGF-BB is not a mitogen for hemSCs and, in adipogenic conditions, significantly inhibits the induction of C/EBPα and PPARγ in both hemSCs and bm-MPCs.

The importance of PDGF signaling in the maintenance of tumor growth is well established. The role of PDGF signaling involves the recruitment of perivascular cells and stabilization of the blood vessels.9, 10 In mice, inhibition of PDGFR-β contributed to reduced tumor growth.32 In a separate study, administering a PDGFR inhibitor stripped mouse tumor endothelial cells of pericytes, thus rendering the tumors more susceptible to chemotherapy.33 PDGF-BB has also been shown to promote endothelial proliferation.34 This may suggest a unique dual role of PDGF signaling in hemangioma pathogenesis. High PDGF levels during the proliferative phase may cause endothelial cells to proliferate while inhibiting the differentiation of adipocytes. We have noted almost a 200-fold increased expression of PDGF-B in hemSCs as compared with the bm-MPCs. This may be due to the primitive state of the hemSCs. Our previous studies show that hemSCs and bm-MPCs share many cell adhesion molecules. The cells are also similar in a number of functional assays except for endothelial and neuroglial differentiation, which is only evident in the hemSCs. These findings show that hemSCs are uncommitted SCs, whereas bm-MPC (when cultured under identical conditions) are limited to the mesenchymal lineage. This enhanced differentiation state of the bm-MPCs is possibly associated with reduced PDGF-B expression.

Elevated PDGF levels in the hemangioma tissue may also be an indirect phenomenon. As all tumors change cellular composition at different stages of growth, it is possible that the changing cellular composition in hemangioma during the involutive phase indirectly leads to reduced PDGF-B content and triggers adipocyte differentiation. We know that the involutive phase is characterized by disappearance of blood vessels, coinciding with the appearance of adipocytes. An exact phenocopy of this is found in our mouse model.14 Endothelial cells have been shown to express PDGF-B, which is involved in mural cell recruitment and vessel stabilization. A decrease in the vascular endothelial cells may, therefore, lead to reduced PDGF-B levels in hemangioma tumors.

Our study represents the first step toward understanding the role of PDGF signaling on the natural history of infantile hemangioma. The findings may have the potential to provide a novel therapeutic target in PDGF signaling, not just for hemangioma but also other conditions, such as obesity and diabetes. Overall, our data point to an inhibitory role for receptor-mediated PDGF signaling in hemangioma involution. Further studies are needed to determine the exact mechanisms underlying altered PDGF-B expression in the hemangioma SCs. PDGF could turn out to be the fundamental intrinsic mechanism of adipocyte development.

Materials and Methods

Hemangioma tissues and cells

Paraffin-embedded hemangioma specimens were obtained from the Department of Pathology Archives at the London Health Sciences Center (LHSC). The proliferating phase of hemangiomas was confirmed by histological analysis. Proliferating hemangioma-derived CD133+ cells (hemSCs) were kindly provided by Dr Joyce Bischoff (Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA, USA). We have previously characterized these hemangioma-derived CD133+ cells by flow cytometry, immunostaining, quantitative RT-PCR, and functional tests including multilineage differentiation.14 Bone marrow-mesenchymal progenitor cells (bm-MPCs; isolated from fresh bone marrow preparations; Lonza Inc., Walkersville, MD, USA) were used as controls. We used bm-MPCs as we have shown adipogenic differentiation in the bm-MPCs under identical conditions (differentiation media and the time point) as the hemSCs.14 All studies were conducted following approval by the Research Ethics Board at The University of Western Ontario (London, Ontario, Canada).

hemSCs were cultured on fibronectin-coated (1 μg/cm2, FC010-10, Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) plates in Endothelial Basal Media-2 (EBM2; Lonza Inc.) supplemented with 20% FBS (Lonza Inc.) and EGM-2 SingleQuots (CC-4176, Lonza Inc.) and 1X antibiotic antimycotic media (PSF; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). All cells were cultured under identical conditions and the experiments were performed with a minimum of three biological replicates (cell preparations from different hemangioma specimens) and three technical replicates.

Immunostaining

Tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated. Antigen retrieval was then carried out in Tris/EDTA buffer (10 mM Trizma-base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Tween-20, pH 9.0) for 15 min at 121 °C using 2100 Retriever (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA). Sections were then blocked in 5% horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) for 30 min and incubated with one of the following antibodies: mouse anti-PDGFR-α (1:200; R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), mouse anti-PDGFR-β (1:50; R & D Systems), mouse anti-α-SMA (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada), and mouse anti-CD31 (1:50; Dako, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Secondary peroxidase-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Vector Laboratories) was used with ImmPACT DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; Vector Laboratories) for detection. Slides were counterstained in hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich) and mounted in Clarion Mounting Medium (Sigma-Aldrich). For fluorescent double-labeling, slides were sequentially stained for two antigens using goat anti-PDGFR-β antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and mouse anti-α-SMA antibody. FITC and texas red-conjugated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) were used for detection. Slides were counterstained with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Hemangioma sections were also stained for phospho-PDGFRs (phospho-PDGFR-β (Y1021) and phospho-PDGFR-α (Y742), Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) using the same protocol. For cell staining, we also used the mouse anti-calponin (Dako) and rabbit anti-desmin (Abcam). Images were taken using the Olympus BX-51 microscope (Olympus Canada Inc., Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada) equipped with a Spot PursuitTM digital camera (SPOT Imaging Solutions, Sterling Heights, MI, USA).

Quantitative real time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the paraffin-embedded hemangioma sections by using High Pure FFPE RNA Micro Kit (Roche Diagnostics Canada, Laval, Quebec, Canada). A similar protocol was employed to isolate RNA from human fetal skin sections (Abcam). For cultured cells, we used RNeasy Mini Plus and Micro Plus Kits (QIAGEN, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The purity of the samples was determined by 260:280 nm absorbance measurements (Quent Spectrophotometer, Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d'Urfe, Quebec, Canada). The quantity was determined by Qubit Broad Range RNA assay in the Qubit Fluorometer (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis was performed with iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (170-8891; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Primers used for RT-PCR were obtained from Qiagen except for PPARγ2, which was obtained from Life Technologies (Burlington, Ontario, Canada): (PDGF-A, QT01664488; PDGF-B, QT00001260; PDGF-C, QT00026551; PDGF-D, QT01667253; PDGFR-α, QT00012719; PDGFR-β, QT00082327; C/EBPα, QT00203357; FABP4, QT01667694; PPARγ2, ATTGACCCAGAAAGCGATTCC and CAAAGGAGTGGGAGTGGTCT; and 18S rRNA, QT00199367). The RT-PCR reactions consisted of 10 μl 2X SYBR Advantage qPCR premix (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), 2 μl primers (10 μM concentration), 2 μl cDNA, and 6 μl of water. 18 S rRNA was used as the housekeeping gene. Data was analyzed by the standard curve method and presented as percent control treatment or control cells.

PDGF-BB measurements and PDGFR tyrosine phosphorylation

hemSCs and bm-MPCs were cultured on FN-coated plates in EBM2 media supplemented with 20% FBS (without SingleQuots or other growth factors). Forty eight hours later, the cell media was collected and PDGF-BB content was measured by Human PDGF-BB Quantikine ELISA (R & D Systems). This immunoassay is specific for human PDGF-BB and free from interference from bovine PDGF-BB. The PDGF-BB standards were used to determine the concentration of PDGF-BB in cell supernatants. Media from bm-MPCs was incubated overnight and hemSC media was incubated for 2 h. Cell lysates were also prepared to measure PDGF-BB levels using the same ELISA. The lysates were also used to measure tyrosine phosphorylated PDGF receptors α (PathScan Phospho-PDGF Receptor α (Tyr849) Sandwich ELISA Kit; Cell Signaling Technology, Pickering, Ontario, Canada) and β (PathScan Phospho-PDGF Receptor β (Tyr751) Sandwich ELISA Kit; Cell Signaling Technology). Phospho-PDGF receptor levels were presented as OD450.

PDGF adipogenesis assays

hemSCs cells were cultured in DMEM media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (control media) or StemPro Adipogenesis Differentiation media (Invitrogen) for 7 days. Media was changed every other day. After 7 days of induction, the cells were either stained with Oil Red O or used for RNA isolation and quantification of adipogenesis. These genes included two transcription factors necessary for adipogenic differentiation (C/EBPα and PPARγ).16, 17 We also examined fatty acid binding protein-4 (FABP-4),15 which is a late adipogenesis marker. The expression of FABP-4 is developmentally regulated by fatty acids and is expressed by mature adipocytes.16, 17

To study the effect of PDGF on hemSC adipogenic differentiation, we included 10 ng/ml PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB, PDGF-BB, SCF, SDF-1, or VEGF-A and -B in the adipogenic differentiation media (all growth factors were obtained from R & D Systems: 221-AA-010, 20-BB-010, 222-AB-010, 255-SC-010, 350-NS-010, 293-VE-010, and 751-VE-025). The media was changed every other day and the cells were exposed to the growth factors for the duration of the 7-day differentiation experiment. Some cells were treated with higher concentrations of the growth factors (concentration shown in the figure legend). PDGF receptor signaling was inhibited by three different means. (1) Cells were pretreated for 30 min with inhibitors of PDGFR tyrosine kinase activity, AG-370 and AG-1296.22–25 AG-370 was used at 20 μM and AG-1296 at 5 μM (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; 10010592-1 and 10010568-1). The cells were then induced to differentiate in adipogenesis media with or without PDGF-BB. In addition to the pre-treatment, the cells were continuously exposed to the inhibitors through media changes. The concentration of these inhibitors was according to previous studies in human cells.22,35,36 (2) We also blocked the PDGFR signaling by using PDGFR-α (MAB322; R & D Systems) and PDGFR-β (AF385, R & D Systems) neutralizing antibodies (both at 2 μg/ml). Similar to the chemical inhibitors, the antibody treatment comprised a 30-min pre-treatment and exposure throughout the 7-day experiment. These antibodies have also been documented to inhibit PDGFR activation in human cells.26 And lastly, we stably knocked down the expression of PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β in the hemSCs (described below).

shRNA plasmid transfections

Cells were plated on FN-coated multi-well plates at a density of 40 000 cells/cm2 in complete EBM2 media. The media was changed to antibiotic/antimycotic-free media 24 h before the transfections. The cells were transfected with control shRNA (sc-108060; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PDGFR-α shRNA (sc-29443-SH; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) plasmid DNA, or PDGFR-β shRNA (sc-29442-SH; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a concentration of 0.25 μg/cm2 surface area. Plasmid DNA was administered using lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated for 7 h and then supplemented with 1 ml of normal growth media (containing PSF). Transfected cells were purified by puromycin treatment for 2 weeks. The knockdown efficiency was determined after puromycin selection and following 6 serial passages by real time RT-PCR.

Oil Red O Staining

Oil-Red-O staining was performed to determine adipogenic differentiation qualitatively. Cells were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 5 min and then dehydrated with propylene. The plates were incubated 8 min at 60 °C with a 0.5% Oil red O stain (Sigma-Aldrich). Following a wash, hematoxylin counterstaining was performed and images were taken using Meiji TC5400 inverted microscope (Meiji Techno American, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with Spot Idea digital camera (SPOT Imaging Solutions).

Cell proliferation and migration

To measure the effect of PDGF-BB on hemSC proliferation, we plated the cells on FN-coated multi-well plates at a density of 2500 cells/cm2. After 24 h in control media, the media was removed and cells were treated with either EBM2/1% FBS (control) or EBM2/1% FBS with 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB. The number of viable cells was determined after 48 h using the tetrazolium salt reagent (WST-1, Clontech) and measuring absorbance at 450 nm in a Multiskan FC Microplate Photometer (Thermo Scientific, Nepean, Ontario, Canada).

Cell migration assay was performed on FN-coated (100 μg/cm2) 6.5-mm Transwells with 8.0 μm pore polycarbonate membrane inserts (BD Falcon Cell Culture inserts; BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). hemSCs were suspended in control media (EBM2/1% FBS) and plated onto the inserts in triplicates, and at a density of 10 000 cells/insert. The lower chamber contained with control media or media supplemented with 10 ng/ml PDGF-BB. After 24 h, the migrated cells were stained with DAPI. Images were taken at × 20 magnification using Olympus BX-51 and cell migration was computed using Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as means±S.E.M. Analysis of variance followed by two-tailed Student’s unpaired t-tests were performed to determine the significance level. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Abbreviations

- α-SMA:

-

alpha-Smooth muscle actin

- bm-MPC:

-

bone marrow-mesenchymal progenitor cell

- C/EBPα:

-

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha

- FABP:

-

fatty-acid-binding protein

- FN:

-

fibronectin

- hemSC:

-

hemangioma stem cell

- PDGF:

-

platelet-derived growth factor

- PDGFR:

-

platelet-derived growth factor receptor

- PPAR:

-

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- SCF:

-

stem cell factor (also known as kit ligand)

- SDF:

-

stromal cell-derived factor

- shRNA:

-

short (or small) hairpin RNA

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, Burrows PE . Vascular anomalies. Curr Probl Surg 2000; 37: 517–584.

Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, Horii KA et al. Prospective study of infantile hemangiomas: clinical characteristics predicting complications and treatment. Pediatrics 2006; 118: 882–887.

Boscolo E, Bischoff J . Vasculogenesis in infantile hemangioma. Angiogenesis 2009; 12: 197–207.

Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, Baselga E, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics 2008; 122: 360–367.

Walter JW, Blei F, Anderson JL, Orlow SJ, Speer MC, Marchuk DA . Genetic mapping of a novel familial form of infantile hemangioma. Am J Med Genet 1999; 82: 77–83.

Ritter MR, Dorrell MI, Edmonds J, Friedlander SF, Friedlander M . Insulin-like growth factor 2 and potential regulators of hemangioma growth and involution identified by large-scale expression analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 7455–7460.

Alvarez RH, Kantarjian HM, Cortes JE . Biology of platelet-derived growth factor and its involvement in disease. Mayo Clin Proc 2006; 81: 1241–1257.

Heldin CH, Westermark B . Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev 1999; 79: 1283–1316.

Lindahl P, Johansson BR, Leveen P, Betsholtz C . Pericyte loss and microaneurysm formation in PDGF-B-deficient mice. Science 1997; 277: 242–245.

Beck L, D'Amore PA . Vascular development: cellular and molecular regulation. FASEB J 1997; 11: 365–373.

Tallquist M, Kazlauskas A . PDGF signaling in cells and mice. Cytokine growth factor rev 2004; 15: 205–213.

Bornfeldt KE, Raines EW, Nakano T, Graves LM, Krebs EG, Ross R . Insulin-like growth factor-I and platelet-derived growth factor-BB induce directed migration of human arterial smooth muscle cells via signaling pathways that are distinct from those of proliferation. J Clin Invest 1994; 93: 1266–1274.

Siegbahn A, Hammacher A, Westermark B, Heldin CH . Differential effects of the various isoforms of platelet-derived growth factor on chemotaxis of fibroblasts, monocytes, and granulocytes. J Clin Invest 1990; 85: 916–920.

Khan ZA, Boscolo E, Picard A, Psutka S, Melero-Martin JM, Bartch TC et al. Multipotential stem cells recapitulate human infantile hemangioma in immunodeficient mice. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 2592–2599.

Baxa CA, Sha RS, Buelt MK, Smith AJ, Matarese V, Chinander LL et al. Human adipocyte lipid-binding protein: purification of the protein and cloning of its complementary DNA. Biochemistry 1989; 28: 8683–8690.

Cristancho AG, Lazar MA . Forming functional fat: a growing understanding of adipocyte differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2011; 12: 722–734.

Gregoire FM, Smas CM, Sul HS . Understanding adipocyte differentiation. Physiol Rev 1998; 78: 783–809.

Greenberger S, Boscolo E, Adini I, Mulliken JB, Bischoff J . Corticosteroid suppression of VEGF-A in infantile hemangioma-derived stem cells. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 1005–1013.

Jinnin M, Medici D, Park L, Limaye N, Liu Y, Boscolo E et al. Suppressed NFAT-dependent VEGFR1 expression and constitutive VEGFR2 signaling in infantile hemangioma. Nat Med 2008; 14: 1236–1246.

Boscolo E, Mulliken JB, Bischoff J . VEGFR-1 mediates endothelial differentiation and formation of blood vessels in a murine model of infantile hemangioma. Am J Pathol 2011; 179: 2266–2277.

Liu X, Duan B, Cheng Z, Jia X, Mao L, Fu H et al. SDF-1/CXCR4 axis modulates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell apoptosis, migration and cytokine secretion. Protein Cell 2011; 2: 845–854.

Bryckaert MC, Eldor A, Fontenay M, Gazit A, Osherov N, Gilon C et al. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor-induced mitogenesis and tyrosine kinase activity in cultured bone marrow fibroblasts by tyrphostins. Exp Cell Res 1992; 199: 255–261.

D'Andrea MR, Mei JM, Tuman RW, Galemmo RA, Johnson DL . Validation of in vivo pharmacodynamic activity of a novel PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor using immunohistochemistry and quantitative image analysis. Mol Cancer Ther 2005; 4: 1198–1204.

Kovalenko M, Gazit A, Bohmer A, Rorsman C, Ronnstrand L, Heldin CH et al. Selective platelet-derived growth factor receptor kinase blockers reverse sis-transformation. Cancer Res 1994; 54: 6106–6114.

Lipson KE, Pang L, Huber LJ, Chen H, Tsai JM, Hirth P et al. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor signaling events after treatment of cells with specific synthetic inhibitors of tyrosine kinase phosphorylation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1998; 285: 844–852.

Faraone D, Aguzzi MS, Ragone G, Russo K, Capogrossi MC, Facchiano A . Heterodimerization of FGF-receptor 1 and PDGF-receptor-alpha: a novel mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of PDGF-BB on FGF-2 in human cells. Blood 2006; 107: 1896–1902.

Bachmeier M, Loffler G . Influence of growth factors on growth and differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes in serum-free conditions. Eur J Cell Biol 1995; 68: 323–329.

Bachmeier M, Loffler G . The effect of platelet-derived growth factor and adipogenic hormones on the expression of CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins in 3T3-L1 cells in serum-free conditions. Eur J Biochem 1997; 243: 128–133.

Vaziri C, Faller DV . Down-regulation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor expression during terminal differentiation of 3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 13642–13648.

Cook JR, Kozak LP . Sn-glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene expression during mouse adipocyte development in vivo. Dev Biol 1982; 92: 440–448.

Widberg CH, Newell FS, Bachmann AW, Ramnoruth SN, Spelta MC, Whitehead JP et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 is a key regulator of early adipogenic events in human preadipocytes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2009; 296: E121–E131.

Bergers G, Song S, Meyer-Morse N, Bergsland E, Hanahan D . Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 1287–1295.

Pietras K, Hanahan D . A multitargeted, metronomic, and maximum-tolerated dose “chemo-switch” regimen is antiangiogenic, producing objective responses and survival benefit in a mouse model of cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 939–952.

Battegay EJ, Rupp J, Iruela-Arispe L, Sage EH, Pech M . PDGF-BB modulates endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro via PDGF beta-receptors. J cell biol 1994; 125: 917–928.

Levitzki A, Gazit A . Tyrosine kinase inhibition: an approach to drug development. Science 1995; 267: 1782–1788.

Gazit A, App H, McMahon G, Chen J, Levitzki A, Bohmer FD . Tyrphostins. 5. Potent inhibitors of platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase: structure-activity relationships in quinoxalines, quinolines, and indole tyrphostins. J Med Chem 1996; 39: 2170–2177.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (ZK; MOP 97783). ER is the recipient of the PC Shah Summer Scholarship from the University of Western Ontario. ZK is a recipient of a New Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (Great-West Life and London Life New Investigator Award).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Edited by A Stephanou

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Roach, E., Chakrabarti, R., Park, N. et al. Intrinsic regulation of hemangioma involution by platelet-derived growth factor. Cell Death Dis 3, e328 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2012.58

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2012.58

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Signaling pathways in the development of infantile hemangioma

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2014)

-

Propranolol inhibits growth of hemangioma-initiating cells but does not induce apoptosis

Pediatric Research (2014)