Abstract

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has been recently used to analyse trabecular bone structure around dental implants. To validate the use of CBCT for three-dimensional (3D) peri-implant trabecular bone morphometry by comparing it to two-dimensional (2D) histology, 36 alveolar bone samples (with implants n=27 vs. without implants n=9) from six mongrel dogs, were scanned ex vivo using a high-resolution (80 µm) CBCT. After scanning, all samples were decalcified and then sectioned into thin histological sections (∼6 μm) to obtain high contrast 2D images. By using CTAn imaging software, bone morphometric parameters including trabecular number (Tb.N), thickness (Tb.Th), separation (Tb.Sp) and bone volume fraction (BV/TV) were examined on both CBCT and corresponding histological images. Higher Tb.Th and Tb.Sp, lower BV/TV and Tb.N were found on CBCT images (P<0.001). Both measurements on the peri-implant trabecular bone structure showed moderate to high correlation (r=0.65–0.85). The Bland–Altman plots showed strongest agreement for Tb.Th followed by Tb.Sp, Tb.N and BV/TV, regardless of the presence of implants. The current findings support the assumption that peri-implant trabecular bone structures based on high-resolution CBCT measurements are representative for the underlying histological bone characteristics, indicating a potential clinical diagnostic use of CBCT-based peri-implant bone morphometric characterisation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone quality, which is a significant determinant of the survival rate of an implant,1,2 depends on the bone mineral density as well as the spatial structure of trabecular bone.3,4 To determine the internal structural properties of peri-implant trabeculae, a proper quantitative morphometry with the imaging resolution superior to trabecular dimensions is desirable.5

Conventionally, bone structure could be assessed in vitro by histomorphometry. This approach remains the gold standard due to its high spatial resolution and image contrast, though it is time-consuming and destructive for secondary measurements.6 Another alternate technique to quantify bone structure in vitro is micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), which has been mainly applied in small animal bones and bone biopsies. In vivo imaging of trabecular bone structure is feasible using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging and multislice CT,7,8 but these are limited by metal artefacts (MRI/CT) or abundant radiation exposure (CT). In contrast, cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT), as an easily available clinical imaging modality developed since the late 1990s,9,10 offers an efficient non-invasive scanning in combination with higher spatial resolution, reduced radiation dose and scan costs.11,12

The value of CBCT in clinical practice has been largely demonstrated in oral and maxillofacial pathology, surgery and implantology,13 mainly focusing on bone density and linear bone measurements.14 Only a few studies described the use of CBCT for trabecular bone structure assessment.12,15,16 Recently, this imaging modality was utilized in a pilot study for analysing peri-implant trabecular bone morphology, suggesting that the latest CBCT equipment with a resolution of 80 µm may probably serve as a three-dimensional (3D) imaging modality for the clinical assessment of the anisotropic trabecular microstructures.17 To date, CBCT for bone morphometric evaluation has been validated with other imaging acquisition modalities such as micro-CT18 or conventional CT19 in human cadavers, further indicating the possibility of quantifying and monitoring changes of trabecular bone microarchitecture in vivo using CBCT. However, less is known about the effectiveness and accuracy of CBCT in comparison to histomorphometry, which will actually add to understanding of previous 3D findings, and help to explain the mechanical behavior of bones. In addition, whether the existence of metal implants could influence the bone morphometry quantification by using CBCT has hardly been documented.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to verify the accuracy of high-resolution CBCT in peri-implant trabecular bone structure analyses using histology as a reference.

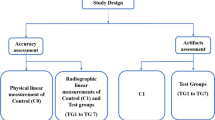

Materials and methods

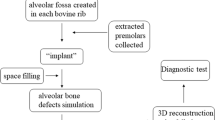

Samples

The current samples consisted of 27 alveolar bone biopsies with custom-made implants and 9 alveolar bone biopsies without the implants (natural healing after teeth extraction, Table 1) retrieved from six mongrel dogs (male, weight 14.8–18.1 kg, age 20–24 months old). The detail of biopsies were outlined in a previous study.17 Briefly, all dogs were sacrificed by means of an intravenous injection of an overdose 0.1 mL·kg−1 Xylazine Hydrochloride (Changchun Military Academy of Medical Sciences, Changchun, China). The jawbones were dissected and defleshed. Then, each implant was removed with a careful preservation of 3−5 mm peri-implant bone as one piece of sample. The experiment protocol was in accordance with the ethical guidelines of KU Leuven (P059-2012-TK).

CBCT image acquisition

All the bone samples were scanned using a high resolution CBCT (Accuitomo 170; Morita, Kyoto, Japan). The exposition and reconstruction parameters for the scan were as following: 0.08 mm voxel size, 360° rotation, ∼950 projections, 90 kV tube voltage, 2.0 mA tube current, 30.8 s scanning time, 40×40 mm field of view, CsI-aSi flat panel detector and 43 (lower jaw)–54 (upper jaw) μSv effective dose.20 To prevent any movement during the scanning process, each sample was mounted vertically into a sponge block, with the long axis of the implant perpendicular to the scanning beam. The calibration of CBCT imager was performed by the manufacturer before the radiographic study.

The original CBCT data were reconstructed as 3D images by CTAn V1.11 software (CTAnalyser; Skyscan, Antwerp, Belgium). Three ring-shaped volumes of interest (VOIs) were automatically selected in a distance of 1 mm away from the surface of the implant, at coronal, middle and apical sections along the axis of the implant as indicated in Figure 1a. All three VOIs were selected through intermediate cross sections by using a custom processing in the CTAn V1.11 by an experienced observer (JVD). Binary regions of interest (ROIs) were further generated by a custom processing algorithm based on adaptive thresholding segmentation,17 excluding implant and cortical bone; trabecular morphometric parameters were then calculated based on this binary segmentation of trabecular bone (Figure 1b).

(a) Three-dimensional models reconstructed from cone-beam computed tomography images in the coronal plane (mesial–distal view). (b) Three VOIs (coronal, middle and apical levels) were automatically selected from (a) along the surface of implant by a custom processing algorithm based on thresholding segmentation. (c) Histological slice of bone specimens (trichrome Masson stain; magnification, ×5) showed the trabecular bone (blue) and bone marrow (pink). (d) Trabecular bone in the binarized histological image at three manually selected ROIs. (e) Similar regions of interest were visually located in the 3D volume (80 μm resolution), corresponding to those in the 2D images (d) with a resolution of 6 μm.

Histology

After CBCT analysis, the samples were decalcified in 0.5 mmol·L−1 EDTA phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 10 months. The implants were then removed from the specimens using surgical forceps. Followed by the dehydration and embedding in paraffin, thin serial sections (∼6 μm) were sectioned along the mesial–distal direction in the middle of the implant or extraction area, where more trabecular bone could be observed. Three serial sections in the most central cut area, corresponding to the greatest dimensions of the samples in length and diameter, were selected and stained with the trichrome Masson stain.

Digital microscopic images of two-dimensional (2D) histological sections were captured by an automated and calibrated camera (Nikon Eclipse 80i; Nikon Co., Tokyo, Japan) and then transferred to grey-level images. The grey-level images were transformed to binary images, enabling a clear separation of trabecular bone and bone marrow (ImageJ, NIH, Maryland, USA). Similar ROIs in the mesial–distal plane, as previously defined in the CBCT measurements, were manually selected by one trained observer (EDS) independently (Figure 1c and 1d). Those selected ROIs were then exported as BMP images and imported into trabecular bone analysis software CTAn for a semi-automatic 2D histomorphometry. Three serial sections per sample were selected to conduct this 2D histomorphometry. Then the results from coronal, middle and apical levels were averaged. All observations were guaranteed to use a standard PC (Intel Pentium Dual-Core, CPU at 3.20 GHz, 4 GB of RAM and a 64-bit operating system) with a 17-inch LCD monitor (Dell, Austin, TX, USA).

Morphometric analysis

CBCT provided measurements obtained directly from reconstructed images based on consecutive 2D images. Only those 3D morphometric parameters that could be compared with 2D histomorphometric measurements were selected for this study. Therefore, 2D and 3D parameters of trabecular bone architecture, as commonly used and directly measured indicators,21 were quantified from CBCT images (VOIs) and histological images (ROIs) using 3D and 2D imaging processing in CTAn, respectively, following the recommendations of the American Society of Bone and Mineral Metabolism22 and Parfitt’s system.23 The formulas and correspondence between these 2D and 3D parameters were described in Table 2. All parameters assumed a plate model for the trabecular bone in the derivation of the equations used for calculation, as a previous study observed for the bone samples used in this study.17

Statistical analysis

Results were summarized by descriptive statistics as mean values with standard deviations and coefficient of variation. Wilcoxon signed-rank test and Spearman correlation test were adopted among all variables analysed in the study, after the normality test for the distribution of data by means of Shapiro–Wilks test. All the hypotheses testing were implemented in STATISTICA 8.0 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) at a significance level of 0.05. The degree of agreement between the measured parameters from CBCT and histological data was compared using the method of Bland and Altman. In this method, the difference between the measurements was plotted against their mean, which was considered to be the best estimate of the true values.

Results

In total, 36 alveolar bone samples (27 with implants and 9 without implants) were analysed. Normal distribution was checked first for all continuous variables according to Shapiro–Wilk test (P<0.05). Descriptive statistics of all variables were presented in Table 3. Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed significant differences between the CBCT and histology for all morphometric parameters (P<0.001). Although trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) were higher on CBCT images than on histological images, lower bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N) were also found on CBCT images. The Spearman correlation between CBCT and histology for all analysed parameters showed significant correlation at P<0.04.

Bland–Altman plots (Figure 2) indicated systematic bias, including constant bias for BV/TV, Tb.Sp and Tb.N, and proportional bias for Tb.Th. For the samples with implant, the smallest bias of measurements in Tb.Th (−0.12 mm) followed by Tb.Sp (−0.28 mm), Tb.N (+0.84 mm−1) and BV/TV (+23%). For the samples without implant, the smallest bias of measurements in Tb.Th (−0.13 mm) followed by Tb.Sp (−0.23 mm), Tb.N (+0.67 mm−1) and BV/TV (+14.02%). The lines of mean under the zero showed a slight overestimation of Tb.Sp and Tb.Th (Figure 2c and 2f), and the lines of mean above the zero demonstrated a slight underestimation of Tb.N by CBCT as compared with the histology (Figure 2g–2h).

Bland–Altman plot comparing the agreement between cone-beam CT (CBCT) and histology in the bone samples with implant (a, c, e, g) and without implant (b, d, f, h) for the following bone structural parameters measurements: bone volume fraction (BV/TV), bone thickness (Tb.Th), bone separation (Tb.Sp) and trabecular number (Tb.N). Positive values represented larger BV/TV and Tb.N obtained from histological data compared with CBCT (a, b, g, h), while negative values showed smaller Tb.Th and Tb.Sp calculated from histology when comparing CBCT (c–f). The dotted lines on the Bland–Altman plot indicated the mean difference±1.96 standard deviations.

Discussion

The present study showed that CBCT imager, with a spatial resolution as high as 80 μm, had significant correlations with histomorphometry on decalcified bone specimens for ex vivo quantification of peri-implant trabecular microstructure. In the evaluation of the agreement between CBCT and histology techniques, a combination of the Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Bland–Altman analyses was applied, which would help to avoid the potential affects by the observed outliers or extreme values.18,24 In this study, we choose a ROI as far as 1mm away from the surface of the implant for both CBCT and histology techniques, due to the bone remodelling is greatest in the bone adjacent to the interface (within 1 mm of the implant) and decreases dramatically with increasing distance from the implant, according to a histomorphometric comparison in four species including humans.25 The reasons for choosing decalcified histological sectioning as the ‘gold standard’ were: (i) better resolution (to ∼6 μm) when compared with the CBCT imaging modality; (ii) the feasibility in colour detection for the bone segmentation; and (iii) no evidence at present that decalcification and embedding technique would significantly influence histomorphometric results.

In this study, comparisons between Tb.Th, Tb.Sp and Tb.N analyses showed highly significant correlation and good agreement between CBCT and histological images. This was well in accordance with a recent study which compared CBCT with micro-CT data on human jawbones.18 Interestingly, CBCT had a tendency to underestimate BV/TV in our study. The latter might be explained by differences between the voxel size (80 μm for CBCT vs. 6 μm for histology), resulting in smaller trabecular boundaries less well defined by CBCT than the histological images. This is consistent with studies which reported decreasing BV/TV and Tb.N with increasing pixel size (lower resolution).21–26 On the other hand, CBCT tended to overestimate Tb.Th and Tb.Sp, but the bias remained relatively low (−0.12 mm and −0.28 mm, respectively). This overestimation could be attributed to the sphere algorithm used for 3D measurement is influenced by the number of nodes (for Tb.Th) or shape and opening of the narrow cavities (for Tb.Sp), as observed in other comparisons of histomorphometry and micro-CT measurements.6,24

However, caution should be taken when applying those trabecular parameters because systematic bias was also observed. There might be several reasons for the systematic biases between CBCT and histology. First, noise was present in the CBCT images as a close fine layer in the surface of titanium implants. Second, 3D CBCT results were calculated as an average value of different VOIs around the implant, while 2D histological results came from the most central section plane of the bone samples. Third, the histological sections in the study were ∼6 μm thick whereas the CBCT slice was 80 μm thick. Finally, the thresholding performed during image reconstruction and binarisation resulted in a systematic impact on subsequent quantitative results. A 10% change in the threshold of micro-CT causes a 5% change in BV/TV.27 Whether this linear relationship exists between morphometric parameters and the thresholding during the image processing remains to be examined for various CBCT imagers.

The quality of CT images could be largely influenced by metal artefacts, which in general leads to a combination of beam hardening, scattering, nonlinear partial volume effect and noise in CT images.28 According to micro-CT findings, a blurred border of 60 μm was found around 3.5 mm-diameter screw-shaped titanium implants.29 Although metal artefacts caused by titanium implant were present along the bone/implant direct interface in this study, specimen-specific threshold values were chosen manually based on the histogram of each image to minimize these artefacts. The intra-examiner reliability of CBCT measurements could be a further proof that the deviation derived from those manually adjustments is still desirable, suggested as another 3D bone structure analyses using CBCT.18 Moreover, it was shown that at the lower part of implant, the range and scale of the artefacts were significantly wider and larger than the upper and middle part.30 To compensate for the heterogeneity of artefact distribution around implants, morphometric analyses in our study were applied at three levels of VOIs along the bone/implant interface. In addition, there was little difference in correlations and biases between the groups with and without implants in this study, suggesting that CBCT is qualified for the evaluation of trabecular bone structures, regardless of the presence or absence of implants.

It has also to be acknowledged that even a micro-CT scanning with low resolution (e.g., large voxel size > 0.1 mm) relative to the size of the structure of interest may cause an underestimation of bone mineral density owing to partial-volume effects and overestimation of object thickness.22 On the other hand, it should also be considered that the fast development of CBCT techniques results in systems enabling to display bone details at a voxel size of 80 µm, being better than the thinnest trabecular thickness of mandibular bone, whether in dogs or humans.5,31 From a clinical point of view, this may provides the possibility for jaw bone structural analysis bases on CBCT.

A limitation of the present study is that the bone samples were scanned ex vivo by CBCT. There was only one implant in each bone sample while CBCT scanning, which means the beam-hardening artefacts derived from multiple implants in the ROI (i.e., number of implants and corresponding spatial distribution) are not considered. Additionally, the stationary situation of the samples might have enhanced the visibility of the trabecular structures because the scans did not subject to patient’s movement. It could also be argued that there was no enough soft tissue surrounding the bone to mimic the real oral scanning situation. Despite this, a previous study already showed that CBCT yields similar morphometric parameters at the 3D level for all protocols with and without water as a mimic of soft-tissue while scanning.16

In summary, considering the good accuracy and strong correlations between CBCT-based and histological bone characteristics, it might be considered feasible to use a high resolution 3D CBCT for clinically diagnosing and analysing trabecular bone structure in general and more specifically around implants. Yet true clinical use can only follow after further studies focusing on the most accurate and reliable morphometric parameters, meanwhile identifying and dropping the biased ones. Such action may further enhance the diagnostic validity of CBCT-based analyses of peri-implant trabecular structures.

References

Jemt T, Lekholm U . Implant treatment in edentulous maxillae: a 5-year follow-up report on patients with different degrees of jaw resorption. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1995; 10: 303–311.

Herrmann I, Lekholm U, Holm S, Kultje C . Evaluation of patient and implant characteristics as potential prognostic factors for oral implant failures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2005; 20: 220–230.

Griffith JF, Genant HK . Bone mass and architecture determination: state of the art. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 22: 737–764.

Felsenberg D, Boonen S . The bone quality framework: determinants of bone strength and their interrelationships, and implications for osteoporosis management. Clin Ther 2005; 27: 1–11.

Imoto H, Yamada A, Shimamura I, Matsunaga S, Ide Y . Influence of mechanical loading on resonance frequency analysis and trabecular structure of peri-implant bone. Prosthod Res Pract 2007; 6: 120–126.

Müller R, van Campenhout H, van Damme B et al. Morphometric analysis of human bone biopsies: a quantitative structural comparison of histological sections and micro-computed tomography. Bone 1998; 23: 59–66.

Majumdar S . Magnetic resonance imaging for osteoporosis. Skelet Radiol 2008; 37: 95–97.

Issever AS, Link TM, Kentenich M et al. Assessment of trabecular bone structure using MDCT: comparison of 64- and 320-slice CT using HR-pQCT as the reference standard. Eur Radiol 2010; 20: 458–468.

Mozzo P, Procacci C, Tacconi A, Martini PT, Andreis IA . A new volumetric CT machine for dental imaging based on the cone-beam technique: preliminary results. Eur Radiol 1998; 8: 1558–1564.

Arai Y, Tammisalo E, Iwai K, Hashimoto K, Shinoda K . Development of a compact computed tomographic apparatus for dental use. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 1999; 28: 245–248.

Liang X, Lambrichts I, Sun Y et al. A comparative evaluation of Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) and Multi-Slice CT (MSCT). Part II: On 3D model accuracy. Eur J Radiol 2010; 75: 270–274.

Hua Y, Nackaerts O, Duyck J, Maes F, Jacobs R . Bone quality assessment based on cone beam computed tomography imaging. Clin Oral Implants Res 2009; 20: 767–771.

De Vos W, Casselman J, Swennen GR . Cone-beam computerized tomography (CBCT) imaging of the oral and maxillofacial region: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; 38: 609–625.

Ibrahim N, Parsa A, Hassan B, van der Stelt P, Wismeijer D . Diagnostic imaging of trabecular bone microstructure for oral implants: a literature review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 20120075.

Corpas Ldos S, Jacobs R, Quirynen M, Huang Y, Naert I, Duyck J . Peri-implant bone tissue assessment by comparing the outcome of intra-oral radiograph and cone beam computed tomography analyses to the histological standard. Clin Oral Implants Res 2011; 22: 492–499.

Van Dessel J, Huang Y, Depypere M, Rubira-Bullen I, Maes F, Jacobs R . A comparative evaluation of cone beam CT and micro-CT on trabecular bone structures in the human mandible. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 20130145.

Huang Y, Van Dessel J, Liang X et al. Effects of immediate and delayed loading on peri-implant trabecular structures: a cone beam CT evaluation. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2013; [Epub ahead of print]

Ibrahim N, Parsa A, Hassan B, van der Stelt P, Aartman I, Wismeijer D . Accuracy of trabecular bone microstructural measurement at planned dental implant sites using cone-beam CT datasets. Clin Oral Implants Res 2013; [Epub ahead of print]

Klintström E, Smedby Ö, Moreno R, Brismar TB . Trabecular bone structure parameters from 3D image processing of clinical multi-slice and cone-beam computed tomography data. Skelet Radiol 2014; 43: 197–204.

Pauwels R, Beinsberger J, Collaert B et al. Effective dose range for dental cone beam computed tomography scanners. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81:267–271.

Perilli E, Parkinson IH, Reynolds KJ . Micro-CT examination of human bone: from biopsies towards the entire organ. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2012; 48: 75–82.

Bouxsein M, Boyd S, Christiansen B, Guldberg R, Jepsen K, Müller R . Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res 2010; 25: 1468–1486.

Parfitt AM, Mathews CH, Villanueva AR, Kleerekoper M, Frame B, Rao DS . Relationships between surface, volume, and thickness of iliac trabecular bone in aging and in osteoporosis—implications for the microanatomic and cellular mechanisms of bone loss. J Clin Inv 1983; 72: 1396–1409.

Chappard D, Retailleau-Gaborit N, Legrand E, Basle MF, Audran M . Comparison insight bone measurements by histomorphometry and microCT. J Bone Miner Res 2005; 20: 1177–1184.

Garetto LP, Chen J, Parr JA, Roberts WE . Remodeling dynamics of bone supporting rigidly fixed titanium implants: a histomorphometric comparison in four species including humans. Implant Dent 1995; 4: 235–243.

Tjong W, Kazakia GJ, Burghardt AJ, Majumdar S . The effect of voxel size on high-resolution peripheral computed tomography measurements of trabecular and cortical bone microstructure. Med Phys 2012; 39: 1893–1903.

Ruegsegger P, Koller B, Muller R . A microtomographic system for the nondestructive evaluation of bone architecture. Calcif Tissue Int 1996; 58: 24–29.

de Man B . X-ray computed tomography. In: Suetens PS Proceedings of the Fundamentals of Medical Imaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University, 2009: 33–62.

Stoppie N, van der Waerden JP, Jansen JA, Duyck J, Wevers M, Naert IE . Validation of microfocus computed tomography in the evaluation of bone implant specimens. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2005; 7: 87–94.

Volpon J, Shimano A . Methods in bone biology in animals: imaging. In: Duque G, Watanabe KS (ed.) Proceedings of the Osteoporosis Research. London: Springer, 2011: 29–36.

Giesen EB, van Eijden TM . The three-dimensional cancellous bone architecture of the human mandibular condyle. J Dent Res 2000; 79: 957–963.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jeanine Santermans and Marc Jans for their technical assistance. The study was supported by grants from the Interfaculty Council for Development Co-operation (IRO), KU Leuven, Belgium. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Dessel, J., Depypere, M. et al. Validating cone-beam computed tomography for peri-implant bone morphometric analysis. Bone Res 2, 14010 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/boneres.2014.10

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/boneres.2014.10

This article is cited by

-

Is the implant-retained overdenture a solution to improve the patient quality of life?

Evidence-Based Dentistry (2022)

-

Effect of platelet-rich and platelet-poor plasma on 3D bone-to-implant contact: a preclinical micro-CT study

International Journal of Implant Dentistry (2021)