Abstract

Background:

Hepatocholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-ICC) is a rare liver tumour for which no data on chemosensitivity exist. The aims of this multicentre study were to evaluate overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and prognostic factors in cHCC-ICC treated by gemcitabine plus platinum as first-line.

Methods:

Unresectable cHCC-ICC treated by gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy between 2008 and 2017 were retrospectively analysed. Diagnosis was based on histology or, in case of ICC or HCC histology, on discordant computerised tomography scan enhancement patterns associated with discordant serum tumour marker elevation suggesting the alternative tumour. OS and PFS were evaluated by Kaplan–Meier method and prognostic factors by Log-rank test and Cox model.

Results:

Among 30 patients included, cHCC-ICC was histologically proven in 22 (73.3%). 18 (60%) received gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin (GEMOX), 9 (30%) GEMOX plus bevacizumab, and 3 (10%) gemcitabine plus cisplatin. RECIST criteria were reported in 28 patients: 8 (28.6%) showed partial response, 14 (50%) stable disease, and 6 (21.4%) tumour progression at first evaluation. Median PFS and OS were 9.0 and 16.2 months, respectively. Serum bilirubin ⩾30 μmol l−1 (P=0.001) and positive serology for HBV and/or HCV (P=0.014) were independent poor prognostic factors for OS.

Conclusions:

Gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy is effective as first-line for advanced cHCC-ICC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Hepatocholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-ICC) is a rare primary hepatic tumour with both, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) histological, features. Its first histological classification dates from 1949 by Allen and Lisa (Allen and Lisa, 1949) and it is now described in the 2010 WHO classification (Theise et al, 2010). The oncogenesis of this tumour remains unclear with hypotheses of the existence of progenitors capable of double differentiation or dedifferentiation of matures hepatocytes (Kim et al, 2004). Moreover, in murine models, existence of several intra-hepatic cell clones with differential potential into hepatocyte and biliary differentiation at the origin of mixed tumours has been described (Piscaglia et al, 2009).

The prevalence of cHCC-ICC varies from 1 to 5% of primary liver cancer in Asia and Western countries in different surgical series (Lee et al, 2006; Wachtel et al, 2008; Bergquist et al, 2016). This tumour is more frequent in males, and it is sometimes associated with chronic viral hepatitis B and C, especially in Asian countries. Cirrhosis is associated in ∼30% of cases (Lee et al, 2006; Chok et al, 2009; Bergquist et al, 2016). About 30% of cHCC-ICC are diagnosed at an advanced stage with synchronous metastases (Wachtel et al, 2008; Wang et al, 2010; Bergquist et al, 2016). The diagnosis may be difficult, and may be based on the analysis of surgical resection specimen or liver biopsy. However, the mixed feature of cHCC-ICC can be misdiagnosed by a biopsy with the identification of the HCC or the ICC histological component only (Tagushi et al, 1996). Some typical cHCC-ICC radiological images have been described on contrast enhanced computerised tomography scan (CT-scan) and magnetic resonance imaging, combining, both, arterial phase enhancement/portal venous washout typical of HCC and progressive fibrous stroma central enhancement typical of ICC. Elevation of tumour serum markers can suggest the diagnosis of HCC or ICC, namely, alpha-fetoprotein (αFP) for HCC, and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9) and carcinoembryonic antigen for ICC. The combination of typical imaging of either HCC or ICC with the elevation of serum tumour markers suggesting the alternative tumour can also help to identify cHCC-ICC (Jarnagin et al, 2002; Tang et al, 2006; Maximin et al, 2014; Li et al, 2016).

There has been no randomised trial investigating the specific management of cHCC-ICC. Few studies have reported the clinical outcomes after resection, liver transplantation, or transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for localised cHCC-ICC (Tagushi et al, 1996; Lee et al, 2006; Kim et al, 2010; Panjala et al, 2010; Wang et al, 2010; Sapisochin et al, 2011; Groeschl et al, 2013; Park et al, 2013; Garancini et al, 2014; Vilchez et al, 2016). Concerning advanced tumours, Sorafenib is the standard of care for HCC with median overall survival (OS) ranging from 6.5 to 10.7 months (Llovet et al, 2008; Cheng et al, 2009), whereas the combination of gemcitabine and platinum (cisplatin or oxaliplatin) is the standard first-line chemotherapy for ICC with median OS of 11.7 months with GEMCIS regimen in the ABC-02 trial (Valle et al, 2010). Few data regarding gemcitabine and platinum-based chemotherapy for HCC have been published. In a large retrospective including 204 patients, median OS was 9 months in patients treated with GEMOX regimen (Zaanan et al, 2013). Bevacizumab, a vascular endothelial growth factor-antibody, in association with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin, has also been investigated in both HCC and advanced biliary-tract cancers but with no demonstrated benefits (Zhu et al, 2006, 2010).

To our knowledge, there is no published data investigating the systemic treatment of advanced cHCC-ICC. The main objective of this retrospective, multicentre study was to evaluate the efficacy of a gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of unresectable, advanced cHCC-ICC.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients with unresectable cHCC-ICC treated with gemcitabine plus platinum-based first-line therapy between January 2008 and February 2017 in six French centres, were retrospectively included. Inclusion criteria were patients older than 18 years and gemcitabine plus cisplatin or oxaliplatin (GEMCIS or GEMOX regimen) as first-line systemic therapy, with ECOG score ⩽2 before initiation of chemotherapy.

We included the patients with histological diagnosis of cHCC-ICC, or in case of ICC or HCC typical histology, with discordant CT-scan enhancement findings associated with serum tumour marker elevations, (typical ICC histology but HCC enhancement pattern: early arterial enhancement with early ‘washout’ corresponding at an hypoattenuating in the portal venous phase, with elevated αFP; typical HCC histology but ICC enhancement pattern: heterogeneous minor peripheral enhancement with gradual enhancement centrally, with elevated CA19-9). Data were last updated in June 2017.

Treatment

The treatment mostly consisted of intra-venous administration of gemcitabine at a standard dose of 1000 mg m−2 within 30 min and oxaliplatin at a standard dose of 85–100 mg m−2 within 2 h, given every 2 weeks (GEMOX) or gemcitabine at a standard dose of 1000–1250 mg m−2 within 30 min and cisplatin at a standard dose of 25 mg m−2 within 1 h on days 1 and 8, every 3 weeks (GEMCIS) with possible dose adjustments. When bevacizumab was associated with GEMOX regimen, the treatment was administrated at dose of 5 mg kg−1 every 2 weeks. Treatments were administrated until disease progression.

Outcome measures

Tumour response rates were assessed by RECIST criteria. OS was defined from the first day of chemotherapy until death from any reason. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined from the first day of chemotherapy until disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. Patients who were alive and did not experience any of these events were censored at the date of the last follow-up.

Statistics

OS and PFS were calculated according to the Kaplan–Meier method. Prognostic factors of OS and PFS were analysed in univariate analysis with the Log-rank test. Variables with a P-value <0.05 or clinically relevant with a P⩽0.20 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis, performed with the Cox proportional hazard model, with a significance level of P<0.05. Analyses were performed using the software Graph Pad Prism 6 and XLStat 2017.

Consent and ethics statement

It was a retrospective study including patients managed with standard care only. The majority of patient was dead or lost to follow-up at the time of data collection. A consent form was not required for this study. The study has been performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and its latter amendments.

Results

Patient and tumour characteristics

Thirty patients were included (Flow chart, Figure 1). The main patients’ characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most of the patients were males (66.7%), 27 (90%) of good general status (ECOG 0–1), 8 patients had cirrhosis (26.7%), 3 patients had positive HBV (10%) and 3 had positive HCV serology (10%), with one co-infection. Most of the patients (53.3%) had synchronous metastases. Two patients (6.67%) initially treated by surgery (one local surgery and one liver transplantation) were included after disease progression. The median follow-up for all the patients was 12.75 months (range 1–51.5 months).

Four patients had a biliary obstruction treated by drainage before chemotherapy. In other patients, elevated serum bilirubin was related to the liver dysfunction.

One patient was excluded because of an ECOG score=3. This patient died after 4 days after the first cycle of GEMOX owing to a liver failure secondary to drug toxicity.

Treatment

Eighteen (60%) and 9 (30%) patients received GEMOX chemotherapy alone or in combination with bevacizumab, respectively. Three patients (10%) received GEMCIS chemotherapy. Overall, the median number of cycles for the first line of chemotherapy was 10 (range 3–28).

In the second line chemotherapy, 14 patients (46.7%) were treated with FOLFIRI (n=6, 42.8%), capecitabine (n=3, 21.4%), LV5FU2 (n=2, 14.3%), or other regimens (LV5FU2-cisplatine, cyclophosphamide, or sunitinib) for the three remaining patients. Five patients (16.7%) received a third line of treatment: FOLFIRI regimen (n=1), FOLFOX regimen (n=1), GEMOX regimen (n=1), sorafenib (n=1), and sunitinib (n=1).

Efficacy

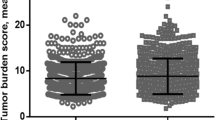

Tumour response

RECIST assessment was performed in 28 patients (93.3%) with measurable disease. At the first evaluation, a partial response was observed in 8 (28.6%), stable disease in 14 (50%), and progression in 6 (21.4%) patients. None of the patients had tumour resection after first-line chemotherapy.

OS

Median OS was 16.2 months. The 1-year and 2-year OS rates were 66% and 26.1%, respectively (Figure 2A).

Median OS of the 22 patients with histological diagnosis of cHCC-ICC was identical, 16.2 months (Figure 2B).

PFS

Median PFS was 9.0 months. The 1-year and 2-year PFS rates were 24.2% and 9.7%, respectively (Figure 2A).

Median PFS of the 22 patients with histological diagnosis of cHCC-ICC was 8.1 months, without significant difference compared with the overall population (Figure 2B).

Prognostic factors

PFS

In univariate analysis, synchronous metastases and serum bilirubin level ⩾30 μmol l−1 were the two significant factors associated with PFS: HR=2.44; 95% CI (1.19–10.03); P=0.023 and HR=2.57; 95% CI (1.32–11.53); P=0.019, respectively. According to the results of the univariate analysis, four factors were included in the multivariate analysis (gender, synchronous metastases, serum bilirubin level ⩾30 μmol l-1 and positive serology for HBV and/or HCV). Synchronous metastases (HR=4.0, 95% CI (1.40–11.40), P=0.009), serum bilirubin level ⩾30 μmol l−1 (HR=4.59, 95% CI (1.43–14.78), P=0.011) and positive serology for HBV and/or HCV (HR=7.27, 95% CI (1.71–30.94), P=0.007) were significant independent poor prognostic factors for PFS. Results are detailed in Table 2.

OS

In univariate analysis, serum bilirubin level ⩾30 μmol l−1 was the only significant poor prognostic factor for OS (HR=3.66; 95% CI (2.50–34.03); P=0.002). According to the results of the univariate analysis, four factors were included in the multivariate analysis (gender, synchronous metastases, serum bilirubin level ⩾30 μmol l−1 and positive serology for HBV and/or HCV). Serum bilirubin level ⩾30 μmol l−1 (HR=10.23, 95% CI (2.51–41.70), P=0.001) and positive serology for HBV and/or HCV (HR=6.89, 95% CI (1.47–32.20), P=0.014) were significant independent poor prognostic factors for OS. Results are detailed in Table 3.

There was no difference in terms of OS and PFS between patients with high serum level of CA 19–9 versus elevated level of αFP.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first published report of systemic treatment for advanced cHCC-ICC. In patients with advanced cHCC-ICC treated with gemcitabine combined with cisplatin or oxaliplatin, the median PFS and OS were 9.0 and 16.2 months, respectively. In addition, the 28.6% response rate and 50% disease control rate suggest a chemosensitivity of these tumours and are close to the results obtain with these drugs in ICC. Serum bilirubin level ⩾30 μmol/l and positive serology for HBV and/or HCV were independent prognostic factors for OS and PFS, whereas the presence of synchronous metastases was independent prognostic factor for PFS.

There are many retrospective data on outcomes after surgical resection of cHCC-ICC, median OS after curative ranging from 4 to 48 months (Chok et al, 2009). The outcomes of liver transplantation are less favorable than for HCC (Panjala et al, 2010; Sapisochin et al, 2011; Groeschl et al, 2013; Park et al, 2013; Garancini et al, 2014; Vilchez et al, 2016). Some studies have investigated TACE for cHCC-ICC. In a retrospective study investigating TACE in 50 patients, median OS was 12.3 months with 70% of patients considered as responders, 85% of them having hypervascularized tumours likely to have a predominant HCC component (Kim et al, 2010). Sorafenib is the standard of care for advanced HCC, with time to progression ranging from 2.8 to 5.5 months and OS ranging from 6.5 to 11.7 months in phase III trials (Llovet et al, 2008; Cheng et al, 2009). Combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin is the standard first-line chemotherapy for advanced ICC, with median PFS and OS of 8.0 and 11.7 months in the ABC-02 trial (Valle et al, 2010). The observed 9.0 months PFS and 16.2 months OS in our study are in accordance with the results obtained in ICC, although no conclusion can be drawn from this retrospective study.

Our patients’ population showed similar characteristics that those described for cHCC-ICC. Median age was 64.5 years, similar to that from the literature (62–65 years), with a higher prevalence of male sex with a sex ratio of 2 (in literature: 65.5–70.8% of men) (Wachtel et al, 2008; Bergquist et al, 2016; Connell et al, 2016). There were 26.7% of associated cirrhosis, as frequently described, two patients had positive HBV serology and two others HCV serology, and one had a co-infection, with two patients without underlying cirrhosis. In the literature, the prevalence of HBV or HCV serology in cHCC-ICC population is heterogenous ranging from 17 to 58% and from 0 to 75%, respectively, with higher rates in Asian population (Jarnagin et al, 2002; Lee et al, 2006; Tang et al, 2006; Chok et al, 2009; Fowler et al, 2013; Bergquist et al, 2016).

There were no differences of outcomes depending on the treatment, GEMOX, GEMCIS, GEMOX-bevacizumab, but no conclusion can be made due to our study design and its small sample size. Only three patients were treated with GEMCIS, making comparisons between GEMOX or GEMCIS regimen not relevant and only nine patients had bevacizumab in association. There are few published data concerning combinations of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin for the treatment of HCC. Recently, a large retrospective multicentre study included 204 patients with advanced HCC treated with GEMOX, reported a 22% response rate, 4.5 months median PFS and 11.0 months median OS (Zaanan et al, 2013). In the treatment of advanced HCC, the combination of gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab has been reported in a phase II study, with 5.3 months median PFS and 9.6 months median OS (Zhu et al, 2006). A systematic review investigated gemcitabine/cisplatin and gemcitabine/oxaliplatin combinations in the treatment of biliary tract cancers in 1470 patients. This study suggests that the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin could have a short survival advantage when cisplatin is administered according to the standard protocol on days 1 and 8 compared with GEMOX regimen administrated every 2 weeks. However, this regimen was associated with increased side effects and toxicities: asthenia, diarrhoea, haematological toxicity, and notably hepatotoxicity, which may not be devoid of consequence in cirrhotic patients (Fiteni et al, 2014). The combination of gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab has also been investigated in advanced biliary-tract cancers with 7 months median PFS and 21.7 months median OS (Zhu et al, 2010). According to these data and our results, the combination of gemcitabine and platinum-based chemotherapy could be a promising regimen for the treatment of cHCC-ICC. There are no data reporting the combination of gemcitabine plus platinum chemotherapy with sorafenib, the strategy that could also be investigated, with a potential activity on both components of cHCC-ICC.

Elevated serum bilirubin was identified as an independent significant poor prognostic factor for OS and PFS. This is an identified poor prognostic factor for both, ICC and HCC (Paik et al, 2009; Vienne et al, 2010). The small size of our population does not allow us to differentiate the etiology of the jaundice (liver dysfunction or biliary obstruction) as independent prognostic factors. Positive serology for HBV and/or HCV was another independent significant poor prognostic factor for OS and PFS. There are few data from prospective studies concerning the prognostic impact of HBV and/or HCV in advanced HCC or ICC, but HBV infection was a poor prognostic factor in patients with HCC in the Asia-Pacific study (Cheng et al, 2009).

Our study has some limitations. First, it is a retrospective study, with limited data about the toxicity of the treatments. There are some missing data (biological markers) and four patients were lost to follow-up (13.3%). We included the patients with histologically documented cHCC-ICC, but also those with HCC or ICC histology but discordant contrast-enhanced CT scan findings associated with discordant tumour marker levels. These criteria to identify cHCC-ICC have been previously proposed (Maximin et al, 2014) and are important to consider as biopsies often lead to a misdiagnosis. In a series of 23 resected cHCC-ICC, all the tumours were misdiagnosed by the pre-operative histology, 20 considered as HCC, three as ICC (Tagushi et al, 1996). The combination of elevated serum tumour markers and enhancement patterns on imaging should strongly suggest the diagnosis of cHCC-ICC in the following circumstances: imaging features of both ICC and HCC, regardless of marker levels; elevation of both αFP and CA 19–9, regardless of imaging appearance; or discordance between imaging and tumour marker elevation (typical HCC enhancement pattern with elevated CA 19–9 or typical ICC enhancement pattern with elevated αFP) (Maximin et al, 2014). The combination of histological, radiological and biological criteria is important to identify cHCC-ICC patients.

In conclusion, these results suggest the efficacy of gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy in the first-line treatment for unresectable cHCC-ICC with good performance status. Prospective trials are needed but challenging because of scarcity of these tumours.

Change history

06 February 2018

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Allen RA, Lisa JR (1949) Combined liver cell and bile duct carcinoma. Am J Pathol 25 (4): 647–655.

Bergquist JR, Groeschl RT, Ivanics T, Shubert CR, Habermann EB, Kendrick ML, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, Truty MJ, Smoot RL (2016) Mixed hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a rare tumor with a mix of parent phenotypic characteristics. HPB 18: 886–889.

Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, Luo R, Feng J, Ye S, Yang TS, Xu J, Sun Y, Liang H, Liu J, Wang J, Tak WY, Pan H, Burock K, Zou J, Voliotis D, Guan Z (2009) Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 10: 25–34.

Chok KS, Ng KK, Cheung TT, Yuen WK, Poon RT, Lo CM, Fan ST (2009) An update on long term outcome of curative hepatic resection for hepatocholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg 33: 1916–1921.

Connell LC, Harding JJ, Shia J, Abou-Alfa GK (2016) Combined intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin Clin Oncol 5: 66.

Fiteni F, Nguyen T, Vernerey D, Paillard MJ, Kim S, Demarchi M, Fein F, Borg C, Bonnetain F, Pivot X (2014) Cisplatin/gemcitabine or oxaliplatin/gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Med 3 (6): 1502–1511.

Fowler KJ, Sheybani A, Parker RA 3rd, Doherty S, M Brunt E, Chapman WC, Menias CO (2013) Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma (biphenotypic) tumors: imaging features and diagnostic accuracy of contrast enhanced CT and MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol 201: 332.

Garancini M, Goffredo P, Pagni F, Romano F, Roman S, Sosa JA, Giardini V (2014) Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a population-level analysis of an uncommon primary liver tumor. Liver Transplant 20: 952–959.

Groeschl RT, Turaga KK, Gamblin TC (2013) Transplantation versus resection for patients with combined hepatocellular carcinomacholangiocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol 107: 608–612.

Jarnagin WR, Weber S, Tickoo SK, Koea JB, Obiekwe S, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Blumgart LH, Klimstra D (2002) Combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: demographic, clinical, and prognostic factors. Cancer 94: 2040–2046.

Kim H, Park C, Han KH, Choi J, Kim YB, Kim JK, Park YN (2004) Primary liver carcinoma of intermediate (hepatocyte–cholangiocyte) phenotype. J Hepatol 40: 298–304.

Kim JH, Yoon HK, Ko GY, Gwon DI, Jang CS, Song HY, Shin JH, Sung KB (2010) Nonresectable combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of the response and prognostic factors after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Radiology 255: 270–277.

Lee WS, Lee KW, Heo JS, Kim SJ, Choi SH, Kim YI, Joh JW (2006) Comparison of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma with hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Today 36: 892–897.

Li R, Yang D, Tang CL, Cai P, Ma KS, Ding SY, Zhang XH, Guo DY, Yan XC (2016) Combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma (biphenotypic) tumors: clinical characteristics, imaging features of contrast-enhanced ultrasound and computed tomography. BMC Cancer 16: 158.

Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Häussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J SHARP Investigators Study Group (2008) Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 359 (4): 378–390.

Maximin S, Ganeshan DM, Shanbhogue AK, Dighe MK, Yeh MM, Kolokythas O, Bhargava P, Lalwani N (2014) Current update on combined hepatocellular- cholangiocarcinoma. Eur J Radiol Open 1: 40–48.

Paik WH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Lee SH, Yoon CJ, Kang SG, Lee JK, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Yoon YB (2009) Palliative treatment with self-expandable metallic stents in patients with advanced type III or IV hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a percutaneous versus endoscopic approach. Gastrointest Endosc 69 (1): 55–62.

Panjala C, Senecal DL, Bridges MD, Kim GP, Nakhleh RE, Nguyen JH, Harnois DM (2010) The diagnostic conundrum and liver transplantation outcome for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Transplant 10: 1263–1267.

Park YH, Hwang S, Ahn CS, Kim KH, Moon DB, Ha TY, Song GW, Jung DH, Park GC, Namgoong JM, Park CS, Park HW, Kang SH, Jung BH, Lee SG (2013) Long-term outcome of liver transplantation for combined hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Transplant Proc 45: 3038–3040.

Piscaglia AC, Shupe TD, Pani G, Tesori V, Gasbarrini A, Petersen BE (2009) Establishment of cancer cell lines from rat hepatocholangiocarcinoma and assessment of the role of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor and hepatocyte growth factor in their growth, motility and survival. J Hepatol 51: 77–92.

Sapisochin G, Fidelman N, Roberts JP, Yao FY (2011) Mixed hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in patients undergoing transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transplant 17 (8): 934–942.

Tagushi J, Nakashima O, Tanaka M, Hisaka T, Takazawa T, Koijiro M (1996) A clinicopathological study on combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 11: 758–764.

Tang D, Nagano H, Nakamura M, Wada H, Marubashi S, Miyamoto A, Takeda Y, Umeshita K, Dono K, Monden M (2006) Clinical and pathological features of Allen's type C classification of resected combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma: a comparative study with hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 10: 987–998.

Theise ND, Nakashima O, Park YN, Nakanuma Y (2010) Combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. In: Who classification of tumours of the digestive system FT Bosman, F Carneiro, RH Hruban, ND Theise, (eds) 4th edn. 225–227. IARC: Lyon, France.

Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP, Roughton M, Bridgewater J ABC-02 Trial Investigators (2010) Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 362 (14): 1273–1281.

Vienne A, Hobeika E, Gouya H, Lapidus N, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Chryssostalis A, Gaudric M, Pelletier G, Buffet C, Chaussade S, Prat F (2010) Prediction of drainage effectiveness during endoscopic stenting of malignant hilar strictures: the role of liver volume assessment. Gastrointest Endosc 72 (4): 728–735.

Vilchez V, Shah MB, Daily MF, Pena L, Tzeng CW, Davenport D, Hosein PJ, Gedaly R, Maynard E (2016) Long-term outcome of patients undergoing liver transplantation for mixed hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma: an analysis of the UNOS database. HPB 18: 29–34.

Wachtel MS, Zhang Y, Xu T, Chiriva-Internati M, Frezza EE (2008) Combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinomas; analysis of a large database. Clin Med Pathol 1: 43–47.

Wang J, Wang F, Kessinger A (2010) Outcome of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma of the liver. J Oncol 1–7.

Zaanan A, Williet N, Hebbar M, Dabakuyo TS, Fartoux L, Mansourbakht T, Dubreuil O, Rosmorduc O, Cattan S, Bonnetain F, Boige V, Taïeb J (2013) Gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a large multicenter AGEO study. J Hepatol 58 (1): 81–88.

Zhu AX, Blaszkowsky LS, Ryan DP, Clark JW, Muzikansky A, Horgan K, Sheehan S, Hale KE, Enzinger PC, Bhargava P, Stuart K (2006) Phase II study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin in combination with bevacizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 24 (12): 1898–1903.

Zhu AX, Meyerhardt JA, Blaszkowsky LS, Kambadakone AR, Muzikansky A, Zheng H, Clark JW, Abrams TA, Chan JA, Enzinger PC, Bhargava P, Kwak EL, Allen JN, Jain SR, Stuart K, Horgan K, Sheehan S, Fuchs CS, Ryan DP, Sahani DV (2010) Efficacy and safety of gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and bevacizumab in advanced biliary-tract cancers and correlation of changes in 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET with clinical outcome: a phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 11 (1): 48–54.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge the contribution of our colleagues from all participating hospitals for helping us to collect their data, especially Vanessa Le Berre (clinical research associate in Poitiers).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Salimon, M., Prieux-Klotz, C., Tougeron, D. et al. Gemcitabine plus platinum-based chemotherapy for first-line treatment of hepatocholangiocarcinoma: an AGEO French multicentre retrospective study. Br J Cancer 118, 325–330 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.413

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.413

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Serine/threonine kinase TBK1 promotes cholangiocarcinoma progression via direct regulation of β-catenin

Oncogene (2023)

-

Identification of the origin of tumor in vein: comparison between CEUS LI-RADS v2017 and v2016 for patients at high risk

BMC Medical Imaging (2022)

-

Management of Combined Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Cholangiocarcinoma

Current Hepatology Reports (2018)