Abstract

Background:

Small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA) is a rare malignancy that accounts for 1–2% of gastrointestinal tumours. We investigated the clinical characteristics, outcomes, and prognostic factors of primary SBA.

Methods:

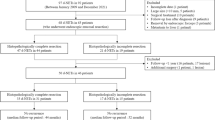

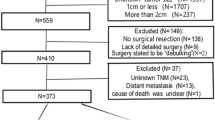

We retrospectively analysed the characteristics and clinical courses of 205 SBA patients from 11 institutions in Japan between June 2002 and August 2013.

Results:

The primary tumour was in the duodenum and jejunum/ileum in 149 (72.7%) and 56 (27.3%) patients, respectively. Sixty-four patients (43.0%) with duodenal adenocarcinoma were asymptomatic and most cases were detected by oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which was not specifically performed for the detection or surveillance of duodenal tumours. In contrast, 47 patients (83.9%) with jejunoileal carcinoma were symptomatic. The 3-year survival rate for stage 0/I, II, III, and IV cancers was 93.4%, 73.1%, 50.9%, and 15.1%, respectively. Multivariate analysis revealed performance status 3–4, high carcinoembryonic antigen, high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), low albumin, symptomatic at diagnosis, and stage III/IV disease were independent factors for overall survival (OS). Ten patients (18.5%) with stage IV disease were treated with a combination of resection of primary tumour, local treatment of metastasis, and chemotherapy; this group had a median OS of 36.9 months.

Conclusions:

Although most SBA patients were diagnosed with symptomatic, advanced stage disease, some patients with duodenal carcinoma were detected in early stage by EGD. High LDH and symptomatic at diagnosis were identified as novel independent prognostic factors for OS. The prognosis of advanced SBA was poor, but combined modality therapy with local treatment of metastasis might prolong patient survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The small intestine accounts for 75% of the length and 90% of the absorptive surface of the gastrointestinal tract. Fortunately, despite the large surface area, the incidence of malignant small bowel tumours is low and makes up <5% of all gastrointestinal tumours (Neugut et al, 1998; Overman, 2009; Aparicio et al, 2014). Small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA) is one of the most common histological subtypes that accounts for ∼40% of malignant small bowel tumours (Bilimoria et al, 2009). According to the EUROCARE data, the incidence of SBA is estimated at ∼3600 new cases per year in Europe (Faivre et al, 2012).

Surgical resection with regional lymph node dissection is considered the standard therapy for localised and resectable disease. Long-term survival can be expected if curative resection is possible, but curative resection is often not feasible in patients with SBA, as this cancer is difficult to detect in the early stages of disease, and most cases are diagnosed in the advanced stage (Dabaja et al, 2004). Although some reports have identified a survival benefit of systemic chemotherapy for patients with advanced SBA, its treatment outcome is not sufficient (Overman, 2009; Zaanan et al, 2010; Aparicio et al, 2014). Therefore, the prognosis of all stages remains poor and the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate is ∼30%, with a median OS time of ∼19 months (Aparicio et al, 2014). Several studies have investigated the prognostic factors of SBA. These have identified advanced age, poorly differentiated carcinoma, T4 tumour stage, and duodenal primary site as important prognostic factors (Howe et al, 1999; Talamonti et al, 2002; Dabaja et al, 2004; Fishman et al, 2006; Wu et al, 2006; Bilimoria et al, 2009; Hong et al, 2009; Halfdanarson et al, 2010; Zaanan et al, 2010; Koo et al, 2011).

As primary adenocarcinoma of the small intestine is rare, most previous studies were retrospective and conducted in single tertiary care centres. Data of these studies were potentially limited by selection bias, and may not accurately reflect true SBA status. On the other hand, some registry database studies, with large data sets and reduced risk of selection bias, have been conducted; however, they may lack detailed data. In this study, we conducted a multicentre observational study to clarify the clinical characteristics, current status, prognostic factors, and outcome of primary SBA.

Materials and methods

Patients

This multicentre retrospective study included a total of 205 patients who were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the small intestine at the following 11 hospitals from June 2002 and August 2013: Okayama University Hospital, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Okayama Saiseikai General Hospital, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital, Shikoku Cancer Center, Japanese Red Cross Okayama Hospital, Kagawa Prefectural Hospital, Mitoyo General Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Society Himeji Hospital, Tsuyama Chuo Hospital, and Sumitomo Besshi Hospital. Patient data were collected after approval by the institutional review boards of each hospital.

Data collection

Data of patients with small intestinal tumours with a histological diagnosis of adenocarcinoma were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were: (1) tumour located on ampulla of Vater, (2) suspected invasive tumour of the pancreas, and (3) small intestinal metastasis from the cancer of other organs. Patients’ medical records were reviewed and the following clinicopathologic parameters were collected: gender, age, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), site of primary tumour, predisposing conditions, histological type, symptoms at diagnosis, Union for International Cancer Control (7th edn) cancer stage based on the tumour, nodes, metastasis (TNM) classification, blood examination dates (carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9), haemoglobin (Hb), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte rate (NLR), platelet (Plt), alanine aminotransferase, creatinine, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), albumin (Alb), sodium), treatment, and survival. We investigated the clinical features, OS, and prognostic factors.

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables are reported as median (range), and all categorical variables are summarised as frequencies (percentages). The Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test was used to compare continuous variables. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Overall survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and the difference was evaluated using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard model was used to identify independent prognostic factors for OS. All tests were two-sided, and a P-value under 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 11 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Two-hundred and five patients from the 11 institutions were included. Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. Median age was 68 years (range, 29–89), and 147 patients (71.7%) were men. Only three patients had predisposing conditions: one patient had familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), one patient had Crohn’s disease, and one patient had Lynch syndrome.

The location of the primary tumour was in the duodenum and jejunoileum in 149 (72.7%) and 56 (27.3%) patients, respectively. The histological type was undifferentiated in 39 patients; these patients accounted for ∼20% of the study cohort.

At the time of diagnosis, 127 patients (62.0%) were symptomatic. We defined intestinal stenosis-related symptoms as abdominal pain or vomiting, and bleeding-related symptoms as melena and anaemia secondary to tumour haemorrhage. The clinical presentation included stenosis-related symptoms in 65 (31.7%) and bleeding-related symptoms in 52 (25.4%) patients. Among patients with duodenal adenocarcinoma, 64 (43.0%) were asymptomatic at diagnosis. This is in contrast with the 47 patients (83.9%) with jejunoileal adenocarcinoma who were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis (P=0.0002). Among asymptomatic patients, 85.9% (55 out of 64) with duodenal carcinoma were incidentally diagnosed by oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which was not specifically performed for the detection or surveillance of duodenal tumours. Five of nine (55.6%) cases of jejunoileal carcinoma were detected by computed tomography, which was performed due to abdominal surgery in four patients and a personal request in one patient.

TNM stages were as follows: 62 (41.6%), 20 (13.4%), 36 (24.2%), and 31 (20.8%) patients with stage 0/I, II, III, and IV duodenal adenocarcinoma, respectively, and 6 (10.7%), 14 (25.0%), 13 (23.2%), and 23 (41.1%) with jejunoileal adenocarcinoma, respectively. Among patients with stage IV disease, the liver and the peritoneum were the most common initial sites of metastatic disease; liver metastasis and peritoneal metastases were present in 27 patients and lung metastases were present in 9 patients.

OS and prognostic factors

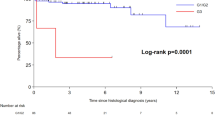

The median follow-up period was 26.7 months (range, 0.2–148.9 months). Eighty-nine patients were followed until death and 115 patients survived during the follow-up period. Figure 1 shows the complement of the Kaplan–Meier curves for TNM staging. The 3-year survival rate for stage 0/I, II, III, and IV disease was 93.4%, 73.1%, 50.9%, and 15.1%, respectively. As the tumour stage advanced, the survival rate progressively decreased.

Table 2 shows the prognostic factors in each stage (stage 0/I and II, stage III, and stage IV) determined by univariate analysis. In stage 0/I and II, age (>68 years), ECOG PS (3–4), undifferentiated type, Hb (<12.5 g dl−1), Alb (<3.8 g dl−1), and symptomatic at diagnosis were prognostic factors for OS. In stage III, male, NLR (⩾3.0), and Plt (2.5 × 104/μl−1) were prognostic factors for OS. In stage IV, age (>68 years), ECOG PS (3–4), CEA (>5.0 mg ml−1), and Alb (<3.8 g dl−1) were prognostic factors. Although not statistically significant, primary site of tumour (duodenum) and LDH (>240 U l−1) tended to be associated with a worse prognosis in stage III.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify independent prognostic factors for OS; the results of these analyses are shown in Table 3. Univariate analysis revealed the following factors were significantly associated with poor OS: age >68 years, poor ECOG-PS (3–4), undifferentiated type, high CEA (>5.0 ng ml−1), high CA19-9 (>37 U ml−1), high NLR (⩾3.0), high LDH (>240 U l−1), low Alb (<3.8 g dl−1), symptomatic at diagnosis, and progression of TNM stage. Multivariate analysis showed PS 3–4 (hazard ratio (HR): 2.26; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.06–4.60; P=0.035), high CEA (HR: 1.88; 95% CI: 1.09–3.22; P=0.024), high LDH (HR: 2.50; 95% CI: 1.23–4.90; P=0.012), low Alb (HR: 1.99; 95% CI:1.11–3.59; P=0.020), symptomatic (HR: 2.27; 95% CI: 1.03–5.34; P=0.042), and stage III and IV (HR: 2.96; 95% CI: 1.52–6.16; P=0.001) were independent prognostic factors for OS.

Treatment modality and survival of stage IV patients

Among 54 patients with stage IV disease, 25 patients (46.3%) underwent resection of the primary tumour, 33 (61.1%) received systemic chemotherapy, and 11 (20.4%) underwent local treatment for distant metastasis such as resection or radiofrequency ablation.

We defined the combined modality therapy group as patients who received all of the following: primary resection, chemotherapy, and local treatment for distant metastasis; the chemotherapy-alone group was defined as those patients who received only chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic lesions; and the best supportive care (BSC) group was defined as patients who did not receive chemotherapy.

Based on these definitions, 10 patients (18.5%) were included in the combined modality therapy group, 23 patients (43.3%) in the chemotherapy-alone group, and 21 patients (38.9%) in the BSC group.

Table 4 shows the comparison of the clinical characteristics of stage IV patients by treatment group. Kaplan–Meier curves of OS by treatment group are shown in Figure 2. The median OS for the combined modality therapy group, chemotherapy group, and BSC group was 36.9, 12.3, and 5.9 months, respectively. The OS of the combined modality therapy group was significantly longer than that of the other therapy groups (HR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.09–0.65; P=0.0021).

Kaplan–Meier curves of OS for stage IV patients by treatment. Combined modality therapy group refers to patients who received primary resection, chemotherapy, and local treatment for distant metastasis; the chemotherapy-alone group refers to patients who received only chemotherapy; and the BSC group refers to patients who did not receive chemotherapy. The OS of the combined modality therapy group was significantly longer than that of the other therapy groups (HR: 0.27; 95% CI: 0.09–0.65; P=0.0021).

Discussion

In this retrospective, multicentre, observational study, we enrolled more than 200 SBA patients at 11 institutions and investigated them in detail. Most previous studies followed a single-centre retrospective design, which were likely limited by selection bias. Although there are several large-scale studies involving data from registry databases, the clinical data may have lacked sufficient detail. We expected our multicentre study to have a lower risk of selection bias than in a single-centre study and our findings likely reflect the current clinical status. We collected detailed data including data that have not been examined before. As a result, we obtained some new findings.

In this study, primary SBA was most common in men in their 60s, and was located in the duodenum in 72.7% of patients. The incidence of undifferentiated adenocarcinoma was 19.0%. Although the patients’ characteristics in the current study were similar to previous studies (Neugut et al, 1998; Dabaja et al, 2004; Wu et al, 2006; Overman, 2009; Zaanan et al, 2010; Aparicio et al, 2014), some new knowledge was gained.

Most SBA patients are diagnosed after symptom onset. Common presenting symptoms of SBA include stenosis-related symptoms such as abdominal pain or vomiting, and bleeding-related symptoms. However, stenosis-related symptoms are rarely identified in early SBA patients, because the small intestinal products are liquid and, therefore, less likely to obstruct. As a result, most SBA patients are diagnosed with advanced disease (Talamonti et al, 2002; Dabaja et al, 2004; Chaiyasate et al, 2008; Hong et al, 2009; Halfdanarson et al, 2010). In this study, when focusing only on duodenal adenocarcinoma, ∼40% of patients were diagnosed with asymptomatic, early-stage disease. These patients were diagnosed incidentally by screening via EGD, which is widely performed in Japan, as directed by the national healthcare system, for detection of gastric cancer. EGD allows for the visualisation of the intestinal tract up to the third portion of the duodenum. Considering the low prevalence of SBA, EGD for the detection of duodenal cancer may not be a reasonable approach. However, our findings suggest that when EGD is performed, regardless of the reason, observing the duodenum with the intention of detecting duodenal cancer is recommended. Alternatively, more than 80% of the patients with jeunoileal adenocarcinoma were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis, and most of them had progressive disease.

Crohn’s disease, FAP, Lynch syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, and celiac disease are known predisposing conditions of SBA (Gyde et al, 1980; Korelitz, 1983; Giardiello et al, 2000; Gardiner and Dasari, 2007; Ikeuchi et al, 2008; Schottenfeld et al, 2009; Swinson et al, 1983). Recently, earlier detection of jejunoileal cancer has been possible due to technical progress in enteroscopic techniques including video capsule endoscopy (VCE) and balloon-assisted enteroscopy. The usefulness of VCE for the detection of small bowel tumours has been reported (Cheung et al, 2010, 2016; Paquissi et al, 2015). However, in this study, there were few patients with those predisposing conditions. Given the low prevalence of SBA and the invasiveness and cost of enteroscopy, screening enteroscopy for patients without predisposing conditions is not rational. Therefore, it is crucial to identify other high-risk predisposing factors that can be easily and less invasively detected.

Previous studies have revealed that advanced age, tumour markers (CEA, CA19-9), primary site in duodenum, poorly differentiated carcinoma, pT4 tumour stage, positive resection margins, positive lymphovascular invasion, number of lymph node metastasis, resection of primary tumour, low Alb, and abnormal Plts were poor prognostic factors in SBA patients (Howe et al, 1999; Talamonti et al, 2002; Dabaja et al, 2004; Fishman et al, 2006; Wu et al, 2006; Agrawal et al, 2007; Overman et al, 2008, 2010; Bilimoria et al, 2009; Hong et al, 2009; Halfdanarson et al, 2010; Zaanan et al, 2010; Koo et al, 2011). In the current study, ECOG PS 3–4, high CEA, high LDH, low Alb, symptomatic at diagnosis, and stages III and IV were found to be independent prognostic factors for OS. Our results were similar to previous studies, but our study also identified high LDH and symptomatic at diagnosis as novel prognostic factors. These factors have not been sufficiently considered in previous studies. LDH is a metabolic enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of lactate to pyruvate, and high LDH is a well-known poor prognostic factor in patients with various malignancies (Zhang et al, 2015; Li et al, 2016). Similar to other malignancies, evaluation of serum LDH might be useful to predict prognosis in SBA patients. Given the limited number of asymptomatic patients with SBA, previous studies have not investigated the effect of the presence or absence of symptoms on disease prognosis. In our study, 69 patients (34.5%) were asymptomatic at diagnosis. Therefore, we were able to identify the presence of symptoms at diagnosis as an independent prognostic factor.

Some studies reported that duodenal carcinoma has a worse prognosis than jejunoileal carcinoma (Howe et al, 1999; Dabaja et al, 2004; Overman et al, 2010; Koo et al, 2011), and others reported that the primary site of tumour was not associated with the prognosis (Talamonti et al, 2002; Wu et al, 2006; Agrawal et al, 2007; Overman et al, 2008; Hong et al, 2009; Halfdanarson et al, 2010; Zaanan et al, 2010). In the current study, patients with duodenal carcinoma were detected in an earlier stage compared with jejunoileal carcinoma. However, primary site was not a significant prognostic factor, which finding may have been affected by the results of stage III patients. While not significant, there was a tendency towards worse OS in duodenal carcinoma in stage III. One reason for this tendency may be the invasiveness of the radical resection of the duodenal carcinoma affected the result (i.e., pancreatoduodenectomy).

Univariate analysis by each stage revealed that prognostic factors (e.g., PS, Alb) in stage 0/I and II patients related to the patient’s general condition, suggesting that tumour factors were not involved in the prognosis at an early stage. In stage III, LDH (>240 U l−1) tended to be associated with a worse prognosis, although there was insufficient statistical power to detect this association, because of the small number of patients. However, even without distant metastasis, LDH may be considered a prognostic factor reflecting the tumour burden when the tumour becomes a locally advanced stage.

Several studies have confirmed the survival benefit of chemotherapy for patients with advanced SBA (Ouriel and Adams, 1984; Jigyasu et al, 1984; Crawley et al, 1998; Dabaja et al, 2004; Locher et al, 2005; Fishman et al, 2006; Overman et al, 2008; Zaanan et al, 2010, 2011; Halfdanarson et al, 2010; Tsushima et al, 2012; Mizushima et al, 2013). However, despite advances in treatment, the prognosis remains poor. Previous studies reported the OS of advanced SBA patients who received systemic chemotherapy was ∼10–20 months (Locher et al, 2005; Overman et al, 2008; Zaanan et al, 2010, 2011; Tsushima et al, 2012). In this study, combined modality therapy was only applicable to patients who were young, with good nutritional status, and with resectable metastatic lesions. Furthermore, the number of patients who underwent combined modality therapy in this study was small. Therefore, it is difficult to make direct comparisons with the other treatment groups. However, the OS of 36.9 months in the combined modality therapy group was clearly long, highlighting the benefit of this treatment protocol. Some studies reported that the biological characteristics of SBA are similar to those of colorectal carcinoma (Agrawal et al, 2007; Cunningham et al, 2010; Aparicio et al, 2013), and that the chemotherapy regimen used to treat colorectal carcinoma can be applied to the treatment of SBA. In colorectal carcinoma, combined modality therapy, including resection of the liver and lung metastasis, is the standard therapy for resectable disease (Fong et al, 1999; Choti et al, 2002; Fernandez et al, 2004; Murata et al, 1998; Kobayashi et al, 1999, 2016; Yedibela et al, 2006; Neeff et al, 2009; Takahashi et al, 2013; Hernández et al, 2016; Ihn et al, 2017), and this approach may be appropriate for SBA. The usefulness of combined modality therapy, including local treatment of resectable metastasis, has not been assessed in previous studies. Therefore, the results of this study might help direct future research related to treatment strategies for advanced SBA.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective study; however, considering the rarity of SBA, the retrospective analysis should be acceptable. Second, patients with Lynch syndrome may be under-represented because family history data was not collected, which likely resulted in an underestimation of patients with predisposing conditions. Third, combined modality therapy was limited to patients whose metastatic lesions were feasible for local treatment; therefore, some selection bias and institutional bias are present. However, when combined modality therapy was feasible, long-term survival was possible.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that when EGD is performed, regardless of the reason, observing the duodenum with the intention of detecting duodenal cancer is recommended. We found ECOG PS 3–4, high CEA, high LDH, low Alb, symptomatic at diagnosis, and stage III and IV were independent prognostic factors for OS. Although the prognosis of advanced SBA was poor, combined modality therapy, including local treatment of distant metastasis, may prolong patient survival.

Ethical statement

The ethics committee of Okayama University Hospital, Kurashiki Central Hospital, Okayama Saiseikai General Hospital, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizens Hospital, Shikoku Cancer Center, Japanese Red Cross Okayama Hospital, Kagawa Prefectural Hospital, Mitoyo General Hospital, Japanese Red Cross Society Himeji Hospital, Tsuyama Chuo Hospital, and Sumitomo Besshi Hospital approved this retrospective study and informed consent was acquired by opt-out method.

Change history

21 November 2017

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Agrawal S, McCarron EC, Gibbs JF, Nava HR, Wilding GE, Rajput A (2007) Surgical management and outcome in primary adenocarcinoma of the small bowel. Ann Surg Oncol 14: 2263–2269.

Aparicio T, Svrcek M, Zaanan A, Beohou E, Laforest A, Afchain P, Mitry E, Taieb J, Di Fiore F, Gornet JM, Thirot-Bidault A, Sobhani I, Malka D, Lecomte T, Locher C, Bonnetain F, Laurent-Puig P (2013) Small bowel adenocarcinoma phenotyping, a clinicobiological prognostic study. Br J Cancer 109: 3057–3066.

Aparicio T, Zaanan A, Svrcek M, Laurent-Puig P, Carrere N, Manfredi S, Locher C, Afchain P (2014) Small bowel adenocarcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Dig Liver Dis 46: 97–104.

Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Wayne JD, Ko CY, Bennett CL, Talamonti MS (2009) Small bowel cancer in the United States: changes in epidemiology, treatment, and survival over the last 20 years. Ann Surg 249: 63–71.

Chaiyasate K, Jain AK, Cheung LY, Jacobs MJ, Mittal VK (2008) Prognostic factors in primary adenocarcinoma of the small intestine: 13-year single institution experience. World J Surg Oncol 6: 12.

Cheung DY, Kim JS, Shim KN, Choi MG Korean Gut Image Study Group (2016) The usefulness of capsule endoscopy for small bowel tumors. Clin Endosc 49: 21–25.

Cheung DY, Lee IS, Chang DK, Kim JO, Cheon JH, Jang BI, Kim YS, Park CH, Lee KJ, Shim KN, Ryu JK, Do JH, Moon JS, Ye BD, Kim KJ, Lim YJ, Choi MG, Chun HJ Korean Gut Images Study Group (2010) Capsule endoscopy in small bowel tumors: a multicenter Korean study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25: 1079–1086.

Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, Sumetchotimetha W, Rangsin R, Schulick RD, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL (2002) Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg 235: 759–766.

Crawley C, Ross P, Norman A, Hill A, Cunningham D (1998) The Royal Marsden experience of a small bowel adenocarcinoma treated with protracted venous infusion 5-fluorouracil. Br J Cancer 78: 508–510.

Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, Lynch HT, Minsky B, Nordlinger B, Starling N (2010) Colorectal cancer. Lancet 375: 1030–1047.

Dabaja BS, Suki D, Pro B, Bonnen M, Ajani J (2004) Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: presentation, prognostic factors, and outcome of 217 patients. Cancer 101: 518–526.

Fernandez FG, Drebin JA, Linehan DC, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Strasberg SM (2004) Five-year survival after resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer in patients screened by positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET). Ann Surg 240: 438–447, discussion 447–450.

Faivre J, Trama A, De Angelis R, Elferink M, Siesling S, Audisio R, Bosset JF, Cervantes A, Lepage C RARECARE Working Group (2012) Incidence, prevalence and survival of patients with rare epithelial digestive cancers diagnosed in Europe in 1995–2002. Eur J Cancer 48: 1417–1424.

Fishman PN, Pond GR, Moore MJ, Oza A, Burkes RL, Siu LL, Feld R, Gallinger S, Greig P, Knox JJ (2006) Natural history and chemotherapy effectiveness for advanced adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: a retrospective review of 113 cases. Am J Clin Oncol 29: 225–231.

Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH (1999) Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 230: 309–318, discussion 318–321.

Gardiner KR, Dasari BV (2007) Operative management of small bowel Crohn’s disease. Surg Clin N Am 87: 587–610.

Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Petersen GM, Booker SV, Cruz-Correa M, Offerhaus JA (2000) Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 119: 1447–1453.

Gyde SN, Prior P, Macartney JC, Thompson H, Waterhouse JA, Allan RN (1980) Malignancy in Crohn's disease. Gut 21: 1024–1029.

Halfdanarson TR, McWilliams RR, Donohue JH, Quevedo JF (2010) A single-institution experience with 491 cases of small bowel adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg 199: 797–803.

Hernández J, Molins L, Fibla JJ, Heras F, Embún R, Rivas JJ Grupo Español deMetástasis Pulmonares de Carcinoma Colo-Rectal (GECMP-CCR) de la Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR) (2016) Role of major resection in pulmonary metastasectomy for colorectal cancer in the Spanish prospective multicenter study (GECMP-CCR). Ann Oncol 27: 850–855.

Hong SH, Koh YH, Rho SY, Byun JH, Oh ST, Im KW, Kim EK, Chang SK (2009) Primary adenocarcinoma of the small intestine: presentation, prognostic factors and clinical outcome. Jpn J Clin Oncol 39: 54–61.

Howe JR, Karnell LH, Menck HR, Scott-Conner C (1999) The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel: review of the National Cancer Data Base, 1985–1995. Cancer 86: 2693–2706.

Ihn MH, Kim DW, Cho S, Oh HK, Jheon S, Kim K, Shin E, Lee HS, Chung JH, Kang SB (2017) Curative resection for metachronous pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer: analysis of survival rates and prognostic factors. Cancer Res Treat 49: 104–115.

Ikeuchi H, Nakano H, Uchino M, Nakamura M, Matsuoka H, Fukuda Y, Matsumoto T, Takesue Y, Tomita N (2008) Intestinal cancer in Crohn's disease. Hepatogastroenterology 55: 2121–2124.

Jigyasu D, Bedikian AY, Stroehlein JR (1984) Chemotherapy for primary adenocarcinoma of the small bowel. Cancer 53: 23–25.

Kobayashi K, Kawamura M, Ishihara T (1999) Surgical treatment for both pulmonary and hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 118: 1090–1096.

Koo DH, Yun SC, Hong YS, Ryu MH, Lee JL, Chang HM, Ryoo BY, Kang YK, Kim TW (2011) Systemic chemotherapy for treatment of advanced small bowel adenocarcinoma with prognostic factor analysis: retrospective study. BMC Cancer 11: 205.

Korelitz BI (1983) Carcinoma of the intestinal tract in Crohn's disease: results of a survey conducted by the National Foundation for Ileitis and colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 78: 44–46.

Li G, Wang Z, Xu J, Wu H, Cai S, He Y (2016) The prognostic value of lactate dehydrogenase levels in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 16: 249.

Locher C, Malka D, Boige V, Lebray P, Elias D, Lasser P, Ducreux M (2005) Combination chemotherapy in advanced small bowel adenocarcinoma. Oncology 69: 290–294.

Mizushima T, Tamagawa H, Mishima H, Ikeda K, Fujita S, Akamatsu H, Ikenaga M, Onishi T, Fukunaga M, Fukuzaki T, Hasegawa J, Takemasa I, Ikeda M, Yamamoto H, Sekimoto M, Nezu R, Doki Y, Mori M (2013) The effects of chemotherapy on primary small bowel cancer: a retrospective multicenter observational study in Japan. Mol Clin Oncol 1: 820–824.

Murata S, Moriya Y, Akasu T, Fujita S, Sugihara K (1998) Resection of both hepatic and pulmonary metastases in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 83: 1086–1093.

Neeff H, Hörth W, Makowiec F, Fischer E, Imdahl A, Hopt UT, Passlick B (2009) Outcome after resection of hepatic and pulmonary metastases of colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 13: 1813–1820.

Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, Suh S, Mukherjee R, Arber N (1998) The epidemiology of cancer of the small bowel. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 7: 243–251.

Ouriel K, Adams JT (1984) Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Am J Surg 147: 66–71.

Overman MJ (2009) Recent advances in the management of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Gastrointest Cancer Res 3: 90–96.

Overman MJ, Hu CY, Wolff RA, Chang GJ (2010) Prognostic value of lymph node evaluation in small bowel adenocarcinoma: analysis of the surveillance epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer 116: 5374–5382.

Overman MJ, Kopetz S, Wen S, Hoff PM, Fogelman D, Morris J, Abbruzzese JL, Ajani JA, Wolff RA (2008) Chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and a platinum compound improves outcomes in metastatic small bowel adenocarcinoma. Cancer 113: 2038–2045.

Paquissi FC, Lima AH, Lopes Mde F, Diaz FV (2015) Adenocarcinoma of the third and fourth portions of the duodenum: the capsule endoscopy value. World J Gastroenterol 21: 9437–9441.

Swinson CM, Slavin G, Coles EC, Booth CC (1983) Coeliac disease and malignancy. Lancet 1: 111–115.

Schottenfeld D, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Vigneau FD (2009) The epidemiology and pathogenesis of neoplasia in the small intestine. Ann Epidemiol 19: 58–69.

Takahashi T, Shibata Y, Tojima Y, Tsuboi K, Sakamoto E, Kunieda K, Matsuoka H, Suzumura K, Sato M, Naganuma T, Sakamoto J, Morita S, Kondo K (2013) Multicenter phase II study of modified FOLFOX6 as neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with unresectable liver-only metastases from colorectal cancer in Japan: ROOF study. Int J Clin Oncol 18: 335–342.

Takatsuki M, Tokunaga S, Uchida S, Sakoda M, Shirabe K, Beppu T, Emi Y, Oki E, Ueno S, Eguchi S, Akagi Y, Ogata Y, Baba H, Natsugoe S, Maehara Y Kyushu Study Group of Clinical Cancer (KSCC) (2016) Evaluation of resectability after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary non-resectable colorectal liver metastases: a multicenter study. Eur J Surg Oncol 42: 184–189.

Talamonti MS, Goetz LH, Rao S, Joehl RJ (2002) Primary cancers of the small bowel: analysis of prognostic factors and results of surgical management. Arch Surg 137: 564–570, discussion 570–571.

Tsushima T, Taguri M, Honma Y, Takahashi H, Ueda S, Nishina T, Kawai H, Kato S, Suenaga M, Tamura F, Morita S, Boku N (2012) Multicenter retrospective study of 132 patients with unresectable small bowel adenocarcinoma treated with chemotherapy. Oncologist 17: 1163–1170.

Wu TJ, Yeh CN, Chao TC, Jan YY, Chen MF (2006) Prognostic factors of primary small bowel adenocarcinoma: univariatef and multivariate analysis. World J Surg 30: 391–398,, discussion 399.

Yedibela S, Klein P, Feuchter K, Hoffmann M, Meyer T, Papadopoulos T, Göhl J, Hohenberger W (2006) Surgical management of pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer in 153 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 13: 1538–1544.

Zaanan A, Costes L, Gauthier M, Malka D, Locher C, Mitry E, Tougeron D, Lecomte T, Gornet JM, Sobhani I, Moulin V, Afchain P, Taïeb J, Bonnetain F, Aparicio T (2010) Chemotherapy of advanced small-bowel adenocarcinoma: a multicenter AGEO study. Ann Oncol 21: 1786–1793.

Zaanan A, Gauthier M, Malka D, Locher C, Gornet JM, Thirot-Bidault A, Tougeron D, Taïeb J, Bonnetain F, Aparicio T Association des Gastro Entérologues Oncologues (2011) Second-line chemotherapy with fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI regimen) in patients with advanced small bowel adenocarcinoma after failure of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy: a multicenter AGEO study. Cancer 117: 1422–1428.

Zhang J, Yao YH, Li BG, Yang Q, Zhang PY, Wang HT (2015) Prognostic value of pretreatment serum lactate dehydrogenase level in patients with solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 5: 9800.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sakae, H., Kanzaki, H., Nasu, J. et al. The characteristics and outcomes of small bowel adenocarcinoma: a multicentre retrospective observational study. Br J Cancer 117, 1607–1613 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.338

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.338

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinicopathological features and prognosis of primary small bowel adenocarcinoma: a large multicenter analysis of the JSCCR database in Japan

Journal of Gastroenterology (2024)

-

Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma: a Nationwide Population-Based Study

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2023)

-

Characteristics and outcome of patients with small bowel adenocarcinoma (SBA)

Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology (2023)

-

Characteristics of synchronous and metachronous duodenal tumors and association with colorectal cancer: a supplementary analysis

Journal of Gastroenterology (2023)

-

An autopsy case of alpha-fetoprotein-producing large duodenal adenocarcinoma

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2023)