Abstract

Background:

Protective effects have been suggested for digoxin against prostate cancer risk. However, few studies have evaluated the possible effects on prostate cancer-specific survival. We studied the association between use of digoxin or beta-blocker sotalol and prostate cancer-specific survival as compared with users of other antiarrhythmic drugs in a retrospective cohort study.

Methods:

Our study population consisted of 6537 prostate cancer cases from the Finnish Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer diagnosed during 1996–2009 (485 digoxin users). The median exposure for digoxin was 480 DDDs (interquartile range 100–1400 DDDs). During a median follow-up of 7.5 years after diagnosis, 617 men (48 digoxin users) died of prostate cancer. We collected information on antiarrhythmic drug purchases from the national prescription database. Both prediagnostic and postdiagnostic drug usages were analysed using the Cox regression method.

Results:

No association was found for prostate cancer death with digoxin usage before (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.56–1.80) or after (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.43–1.51) prostate cancer diagnosis. The results were also comparable for sotalol and antiarrhythmic drugs in general. Among men not receiving hormonal therapy, prediagnostic digoxin usage was associated with prolonged prostate cancer survival (HR 0.20, 95% CI 0.05–0.86).

Conclusions:

No general protective effects against prostate cancer were observed for digoxin or sotalol usage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Previous epidemiological studies have suggested that the antiarrhythmic drug digoxin may have prostate cancer (PCa)-protective effects especially in long-term usage (Platz et al, 2011; Wright et al, 2014; Kaapu et al, 2015). The proposed mechanism at the cellular level is digoxin-induced inhibition of the plasma membrane Na+/K+-ATPase, which elevates the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, enhancing apoptosis of cancer cells (McConkey et al, 2000; Prevarskaya et al, 2014). Furthermore, HIF-1α has been reported to be overexpressed in PCa cells. This overexpression might stimulate tumour growth and metastasis. Digoxin has been proposed to inhibit HIF-1α protein synthesis and the expression of HIF-1α target genes in prostate tumours (Zhang et al, 2008). A previous cohort study has linked use of digoxin and other HIF-1α-inhibitory drugs with delayed occurrence of castration resistance and distant metastases in PCa patients treated with androgen-deprivation therapy (Ranasinghe et al, 2014).

Usage of beta-blockers may be associated with decreased cancer incidence (Monami et al, 2013) and cancer mortality (Choi et al, 2014). We have previously shown in a case–control study that use of the antiarrhythmic drug sotalol, with both beta-blocker and K+-channel inhibitor properties, decreased the risk of advanced PCa (Kaapu et al, 2016). Some studies also suggest that other beta-blockers may be associated with prolonged survival of PCa patients (Grytli et al, 2014; Lu et al, 2015), although conflicting results have been presented as well (Assayag et al, 2014; Cardwell et al, 2014).

Currently, there is little knowledge about the effect of digoxin or sotalol use on PCa mortality; two published studies suggest no connection with digoxin use (Flahavan et al, 2014; Lip et al, 2015). However, digoxin use may prolong the doubling time of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level in PCa patients (Lin et al, 2014). No studies have evaluated the association between other antiarrhythmic drugs and PCa mortality.

We evaluated whether the use of digoxin, sotalol or other antiarrhythmic drugs is related to PCa survival in the Finnish Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (FinRSPC).

Materials and methods

Study cohort

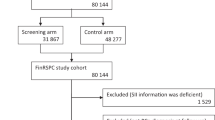

Our study population consisted of men within FinRSPC, the largest component of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. The detailed trial protocol has been described previously (Kilpeläinen et al, 2013). In brief, a total of 80 458 men aged 55–67 years were identified in the years 1996–1999 and randomised to either PCa screening with a PSA test at 4-year intervals (31 866 men, the screening arm) or no intervention (48 278 men, the control arm). Prostate cancer cases diagnosed among the study population were identified from the Finnish Cancer Registry. During 1996–2009, 6537 new cases of PCa were diagnosed. Available information on cancer cases included the Gleason grade, TNM stage, primary treatment (surgery, radiation therapy, endocrine treatment or surveillance) and the serum PSA concentration. Each case was categorised as either low/medium risk or high risk according to the criteria of the European Association of Urology.

Causes of death among the study population in 1996–2012 were obtained from Statistics Finland, which has been found to be a reliable source of information by the FinRSPC cause-of-death committee (Mäkinen et al, 2008). In this study, deaths where PCa (ICD-10 code C61) was recorded as the primary cause of death were considered as PCa deaths. Cases with ICD-code C61 as the intermediate or contributory cause of death were analysed separately for PCa-related mortality.

The study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Pirkanmaa health-care district, Finland (tracking number R10167).

Information on medication use

The information on antiarrhythmic drug purchases was collected from the reimbursement database of the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (SII). The database includes the information on physician-prescribed medication purchases during 1995–2009. This linkage was based on the unique personal identification number assigned for all Finnish residents. The database contains records of the date, the number of packages acquired and the number and dosage of the pills for each purchase.

All Finnish residents are entitled to a reimbursement provided by the SII for every physician-prescribed drug purchase in the outpatient setting (Hemminki and Bomann-Larsen, 1981). The database covers all antiarrhythmic drugs, including amiodarone, digoxin, disopyramide, etilefrine, flecainide, quinidine, mexiletine, procainamide, propafenone and sotalol. Additional information was obtained concerning use of statins, antidiabetic medication (oral drugs and insulins), antihypertensive medication (beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors/ATII receptor blockers, calcium-channel blockers, diuretics and other types of drugs, such as methyldopa and clonidine), aspirin and other NSAIDs, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors and alpha-blockers. The database does not cover over-the-counter medication purchases or the drugs used by hospital inpatients.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the baseline characteristics of ever- vs never-users of digoxin and sotalol were compared separately using the chi-square test (categorical variables) and the Mann–Whitney U-test (continuous variables).

The analysis was limited to include only men who have used some antiarrhythmic drug during the study period to minimise the effects of confounding by indication. The association between usage of digoxin and sotalol and risk of PCa-specific death was estimated using the Cox regression model. Follow-up started at PCa diagnosis. The analysis was conducted separately for prediagnostic and postdiagnostic use of medication.

Antiarrhythmic drug usage before PCa diagnosis was analysed as a time-independent variable fixed at baseline. Participants using medication at the time of diagnosis were classified as active users. If the medication had been used previously but not during the year of diagnosis, the participant was classified as a previous user. Active users and previous users were also combined into one category called ‘any users’.

Antiarrhythmic drug usage after PCa was analysed as a time-dependent variable. The medication use status was updated each year, based on yearly medication purchases during the follow-up. All participants were categorised as non-users until the first medication purchase. At the first purchase, the exposure status changed to user. Men who discontinued previous drug purchases remained in the category of any users to minimise bias owing to selective discontinuation of drug usage during the terminal phases of cancer.

We used three differently adjusted regression models: (1) age-adjusted (2) additionally adjusted for tumour risk group and (3) multivariable-adjusted (further adjustment for FinRSPC trial arm and use of other drugs during the study period: drugs used for benign prostatic hyperplasia, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia or hypertension and aspirin and other NSAIDs). To avoid overadjustment of the analysis, we did not adjust for PCa treatment, as the treatment depends on patient age, tumour characteristics and co-morbidities, all of which were adjusted for, and the effect of drug use may occur through tumour characteristics.

The annual amount of medication use was estimated by adding together the milligram amount of all purchases of a given drug (dosage multiplied by the number of pills) during the year. We standardised the amount of usage between different antiarrhythmic drugs by dividing the yearly milligram amount with the drug-specific average defined daily dose (DDD) published by WHO (2015). Intensity of drug use (DDDs per year) was calculated by dividing the yearly cumulative amount with the number of years of usage.

The amount (DDDs), duration (years) and intensity (DDDs per years) of postdiagnostic antiarrhythmic drug use were also time-dependent variables, which were updated by recorded medication purchases during each year of follow-up. At discontinuation, cumulative medication use remained at the reached level.

We evaluated survival trends by amount, duration and intensity of either digoxin or sotalol use by dividing the cohort into two subgroups according to the median of cumulative amount/duration/intensity of drug use. The over-median and under-median subgroups were compared with the users of other antiarrhythmic drugs.

Effect modification by age, tumour characteristics, screening trial arm, usage of other drug groups and primary treatment was evaluated in subgroup analyses stratified according to these variables. In the subgroup analyses, non-users were used as a reference. Prediagnostic and postdiagnostic antiarrhythmic drug usages among these subgroups were analysed separately. The statistical significance of effect modification was evaluated by adding an interaction term to the Cox regression model between the variable of interest and medication use.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to characterise the association between digoxin use and PCa-specific survival. The impact of medication use during the final years of life was evaluated in a lag time analysis, where exposure was lagged to occur 1–3 years later than the actual purchases. Possible confounding owing to background variables was controlled by calculating a propensity score, as described previously (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1984), and stratifying the analysis according to the median of the propensity score. In short, antiarrhythmic drug use was analysed as the dependent variable using the logistic regression method. The explanatory variables were age at diagnosis, use of other drugs and the tumour risk group. Propensities from each background variable were summed together to form a total propensity score, which was then used to stratify the population. Competing risk regression analyses with non-cancer deaths as the competing risk were carried out according to the method described by Fine and Gray (1999) in order to compare the risks of prostate cancer death among users of digoxin and users of sotalol to men using other types of antiarrhythmic drugs.

All the statistical tests mentioned above are two-sided. P-values of ⩽0.05 were considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for data analyses.

Results

Population characteristics

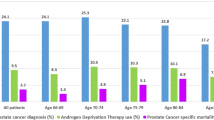

In the study population of 6537 PCa cases, the median age at diagnosis was 63 years among prediagnostic ever- and never-users of antiarrhythmic drugs, as well as among digoxin and sotalol users. In total, 730 men (11.2%) had used antiarrhythmic drugs during the follow-up, 485 (7.4%) had used digoxin and 241 (3.7%) sotalol. The median exposures to digoxin and sotalol were 480 and 380 DDDs (ranges 100–1400 and 50–1500 DDDs), respectively. During the median follow-up of 7.5 years after PCa diagnosis, 1861 (28.5%) subjects died, 617 (9.4%) with PCa as the underlying cause of death, including 70 men with any antiarrhythmic drug use, 48 men with digoxin use and 26 with sotalol use.

Among ever-users of antiarrhythmic drugs, the proportion of men with Gleason 7–10 cancer was slightly lower compared with never-users (39.4% vs 42.2%). Also the prevalence of Gleason 8–10 PCa was lower among the users (12.2% vs 14.1%). The same trend was observed between ever- and never-users of digoxin or sotalol (39.2% vs 42.0% and 40.6% vs 42.0%, respectively). The proportion of metastatic cases did not vary by antiarrhythmic drug usage (Table 1).

The usage of other drug groups (NSAIDs, aspirin, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors, alpha-blockers, antihypertensive drugs, antidiabetic drugs and statins) was generally more frequent among the antiarrhythmic drug users compared with the non-users (Table 1).

Antiarrhythmic drug use before prostate cancer diagnosis

Digoxin use was not significantly associated with the risk of PCa death (age-adjusted HR 1.33, 95% CI 0.99–1.77 and HR 1.53, 95% CI 0.88–2.65 for any use and current use, respectively; Table 2). Further adjustment for tumour risk group and use of other medications did not change the result (Figure 1). Non-significantly increased hazard ratios were observed among cases where the cumulative amount, duration or intensity of digoxin usage was above the median (Table 2).

Prediagnostic sotalol usage did not affect the risk of PCa death and no clear risk trends were observed by cumulative usage (Table 2).

Antiarrhythmic drug use after prostate cancer diagnosis

Postdiagnostic digoxin usage was not significantly associated with PCa survival (age-adjusted HR 1.19, 95% CI 0.72–1.97 and HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.60–1.87 for any and current use, respectively; Table 3). Again, further model adjustment did not change the result. No consistent survival differences were observed by cumulative amount and duration of postdiagnostic digoxin use (Table 3).

Postdiagnostic usage of sotalol was generally not significantly associated with the risk of PCa death (multivariable-adjusted HR 1.53, 95% CI 0.78–2.98 for any use; Table 3). Only men who had discontinued sotalol usage had an elevated risk of PCa death (HR 2.73, 95% CI 1.28–5.84). Risk increases were observed only in short-term use at low cumulative doses and low intensity and were no longer significant after adjustment for other prognostic factors.

Subgroup analyses

Use of ADT as primary treatment of PCa did not modify the effect of digoxin (P for interaction 0.60), although a significant risk decrease was observed among men not receiving ADT and using digoxin before diagnosis (HR 0.20, 95% CI 0.048–0.86).

The risk of PCa death was neither lowered nor elevated in the other analysed subgroups for digoxin use before diagnosis (Figure 2) or postdiagnosis (Figure 3).

Sensitivity analyses

The risk of PCa death was compared between all antiarrhythmic drug users and non-users to see whether there is general risk variance associated with the usage. When men with any antiarrhythmic drug usage before PCa diagnosis were compared with never-users, no risk difference was observed (HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.82–1.65). The results were similar for men with any antiarrhythmic drug usage after the diagnosis (HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.61–1.44). Furthermore, digoxin users were compared with non-users of antiarrhythmic drugs. We found no material survival association for digoxin use before (HR 1.22, 95% CI 0.87–1.72) or after (HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.72–1.65) the diagnosis. Further adjustment for primary and secondary PCa treatment did not modify the main results.

In a separate analysis, we used antihypertensive drug users as the reference group, because these drugs are often used in the management of cardiac insufficiency, which is also a common indication for digoxin use. There was no risk association observed in this analysis, neither for prediagnostic (HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.70–1.74) nor for postdiagnostic drug usage (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.55–1.62).

No risk association was seen for PCa-related deaths (HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.54–1.56 for prediagnostic and HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.60–1.68 for postdiagnostic digoxin usage).

Digoxin usage was not associated with PCa death in lag-time analyses either: the risk estimate in the analysis with a 1-year lag was 1.40, 95% CI 0.86–2.28 and in the 3-year lag time analysis 1.34, 95% CI 0.83–2.19.

In an analysis stratified by the median of the propensity scores, the effects of digoxin use were comparable among men with low and high propensity for antiarrhythmic drug use (usage before diagnosis HR 1.72 95% CI 0.85–3.46 and 1.45 95% CI 0.81–2.59; usage after diagnosis HR 0.79 95% CI 0.30–2.12 and 1.26 95% CI 0.67–2.39, respectively). The findings for sotalol were similar. Further, digoxin or sotalol uses were not associated with the risk of PCa death in an analysis adjusted for the propensity score.

Digoxin use, both before and after PCa diagnosis, was not associated with risk of PCa death when non-cancer deaths were analysed as a competing cause of death (HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.72–1.07 and HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.60–1.22, respectively).

Overall risk of death and death owing to causes other than prostate cancer by digoxin and sotalol use are reported in Supplementary Table S1. Digoxin users were at greater risk of dying from non-PCa causes compared with other antiarrhythmic drug users, whereas the risk was lowered among sotalol users. Furthermore, we performed a Cox regression that included only those variables that showed a significant association with the risk of PCa death in crude analyses. Results were comparable to the main analysis (Supplementary Table S2).

Discussion

Our study found no significant association between PCa survival and digoxin or sotalol usage. The timing of the drug usage did not affect the results, as no difference was observed between survival estimates of prediagnostic and postdiagnostic digoxin usage. No dose–response was found in the risk by the cumulative amount, duration or intensity of digoxin use. Furthermore, the results did not differ between men in the screening and control arms. Thus our results do not support the PCa-protective effects of this antiarrhythmic agent.

A previous cohort study including 5732 PCa patients reported that digoxin usage at PCa diagnosis did not associate with PCa survival (Flahavan et al, 2014). Our findings are in concordance with the results reported previously, and some new aspects are considered. We analysed prediagnostic and postdiagnostic drug usage separately, providing new information on the possible importance of the timing of drug usage. The median follow-up time in our study was 7.5 years, while in the previous study it was 4.3 years (Flahavan et al, 2014). This increase in the median follow-up time is important when studying PCa death as an end point, as PCa often has a good long-term survival.

The association between digoxin usage and PCa risk has been more comprehensively studied than PCa survival. Nevertheless, incongruous results have been reported. Platz et al (2011) reported digoxin users having a lowered PCa risk compared with non-users in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The risk decrease was more distinct among men who had used digoxin for >10 years. We have previously demonstrated in this study population that digoxin use may be linked with a lower risk of Gleason 7–10 PCa, specifically in men under systematic PCa screening (Kaapu et al, 2015). The current study shows that this possible benefit in PCa risk does not translate into improved disease-specific survival.

The only subgroup in the present study where a possible protective effect of digoxin was observed was the men who did not receive ADT as the primary treatment choice. Although the interaction term was non-significant, this suggests that ADT may modify the effects of digoxin in PCa patients. Our results do not support the previous study reporting digoxin and other HIF-1α inhibitors to enhance the efficacy of ADT (Ranasinghe et al, 2014). On the other hand, digoxin is a phytoestrogen affecting the estrogen receptor (Rifka et al, 1978). Thus the protective effects could be diluted in men managed with ADT but observed in men managed otherwise.

The decreased risk of advanced PCa observed among sotalol users in our previous study (Kaapu et al, 2015) did not translate into a survival benefit in the present study. Additionally, our recent cohort study (Kaapu et al, 2016) lacked this association and therefore we must consider the possible protective effects of sotalol usage in relation to prostate cancer death as uncertain.

Several strengths can be identified in our study. Men living in two different metropolitan areas in Finland comprised a comprehensive and representative study population. The study cohort enabled us to assess reliably the effects of relatively infrequent antiarrhythmic agents. Furthermore, information on medication use was collected from a national prescription database, thus allowing us to evaluate both prediagnostic and postdiagnostic drug usage. Recall bias was avoided, as the information on medication use was not self-reported; the database records medication purchases regardless of cancer status. In addition, information on the treatment and characteristics of the cancer was available from medical records.

Analyses on the risk of death among digoxin users are easily influenced by competing causes of death as the drug is used in the management of atrial fibrillation and cardiac insufficiency, both of which are strongly associated with cardiovascular diseases. This was demonstrated by the increased risk of non-PCa death among digoxin users. To minimise the possibility of confounding by indication, users of other antiarrhythmic drugs were used as a reference group. In the multivariable-adjusted analyses, the influence of tumour risk group and usage of other medication were considered. Furthermore, we were able to evaluate the role of screening in the survival association, as men in the screening arm and in the control arm were analysed separately. Additionally, performing the analysis with competing risk regression did not change the result.

A few limitations should be considered. The indications for antiarrhythmic drugs prescribed to men in the study were not available. Most other diseases among the men could be adjusted for in the multivariable analyses as described above, but no information on untreated chronic conditions was available. Furthermore, only 48 digoxin users died of PCa. Thus our analysis was probably underpowered to detect small differences in PCa survival.

Conclusion

We found no clear association between digoxin or sotalol usage and PCa-specific survival.

Change history

22 November 2016

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Assayag J, Pollak MN, Azoulay L (2014) Post-diagnostic use of beta-blockers and the risk of death in patients with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer 50: 2838–2845.

Cardwell CR, Coleman HG, Murray LJ, O’Sullivan JM, Powe DG (2014) Beta-blocker usage and prostate cancer survival: a nested case-control study in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink cohort. Cancer Epidemiol 38: 279–285.

Choi CH, Song T, Kim TH, Choi JK, Park JY, Yoon A, Lee YY, Kim TJ, Bae DS, Lee JW, Kim BG (2014) Meta-analysis of the effects of beta blocker on survival time in cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 140: 1179–1188.

Criteria of European Association of Urology for prostate cancer risk groups (updated Mar 2015; cited 9 Dec 2015). Available from http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/EAU-Guidelines-Prostate-Cancer-2015-v2.pdf.

Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94: 496–509.

Flahavan EM, Sharp L, Bennett K, Barron TI (2014) A cohort study of digoxin exposure and mortality in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int 113: 236–245.

Grytli HH, Fagerland MW, Fossa SD, Tasken KA (2014) Association between use of beta-blockers and prostate cancer-specific survival: a cohort study of 3561 prostate cancer patients with high-risk or metastatic disease. Eur Urol 65: 635–641.

Hemminki E, Bomann-Larsen P (1981) Drug reimbursement in four Nordic countries. Scand J Soc Med 9: 1–10.

Kaapu KJ, Ahti J, Tammela TL, Auvinen A, Murtola TJ (2015) Sotalol, but not digoxin is associated with decreased prostate cancer risk: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer 137: 1187–1195.

Kaapu KJ, Murtola TJ, Määttänen L, Talala K, Taari K, Tammela TLJ, Auvinen A (2016) Prostate cancer risk among users of digoxin and other antiarrhythmic drugs in the Finnish Prostate Cancer Screening Trial. Cancer Causes Control 27: 157–164.

Kilpeläinen TP, Tammela TL, Malila N, Hakama M, Santti H, Määttänen L, Stenman UH, Kujala P, Auvinen A (2013) Prostate cancer mortality in the Finnish Randomized Screening Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 105: 719–725.

Lin J, Zhan T, Duffy D, Hoffman-Censits J, Kilpatrick D, Trabulsi EJ, Lallas CD, Chervoneva I, Limentani K, Kennedy B, Kessler S, Gomella L, Antonarakis ES, Carducci MA, Force T, Kelly WK (2014) A pilot phase II Study of digoxin in patients with recurrent prostate cancer as evident by a rising PSA. Am J Cancer Ther Pharmacol 2: 21–32.

Lip S, Carlin C, McCallum L, Touyz RH, Dominiczak AF, Padmanabhan S (2015) Incidence and prognosis of cancer associated with digoxin and common antihypertensive drugs. J Hypertens 33 (Suppl 1): E45.

Lu H, Liu X, Guo F, Tan S, Wang G, Liu H, Wang J, He X, Mo Y, Shi B (2015) Impact of beta-blockers on prostate cancer mortality: a meta-analysis of 16,825 patients. Onco Targets Ther 8: 985–990.

Mäkinen T, Karhunen P, Aro J, Lahtela J, Määttänen L, Auvinen A (2008) Assessment of causes of death in a prostate cancer screening trial. Int J Cancer 122: 413–417.

McConkey DJ, Lin Y, Nutt LK, Ozel HZ, Newman RA (2000) Cardiac glycosides stimulate Ca2+ increases and apoptosis in androgen-independent, metastatic human prostate adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res 60: 3807–3812.

Monami M, Filippi L, Ungar A, Sgrilli F, Antenore A, Dicembrini I, Bagnoli P, Marchionni N, Rotella CM, Mannucci E (2013) Further data on beta-blockers and cancer risk: observational study and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Curr Med Res Opin 29: 369–378.

Platz EA, Yegnasubramanian S, Liu JO, Chong CR, Shim JS, Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Giovannucci E, Nelson WG (2011) A novel two-stage, transdisciplinary study identifies digoxin as a possible drug for prostate cancer treatment. Cancer Discov 1: 68–77.

Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Shuba Y (2014) Ca2+ homeostasis in apoptotic resistance of prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 322: 1326–1335.

Ranasinghe WK, Sengupta S, Williams S, Chang M, Shulkes A, Bolton DM, Baldwin G, Patel O (2014) The effects of nonspecific HIF1α inhibitors on development of castrate resistance and metastases in prostate cancer. Cancer Med 3: 245–251.

Rifka SM, Pita JC, Vigersky RA, Wilson YA, Loriaux DL (1978) Interaction of digitalis and spironolactone with human sex steroid receptors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 46: 338–344.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DP (1984) Reducing bias in observational studies using subclassification on the propensity score. J Am Stat Assoc 79: 516–524.

WHO (2015) WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD Index 2015 (updated 9 Dec 2013; cited 9 Dec 2015). Available from http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/.

Wright JL, Hansten PD, Stanford JL (2014) Is digoxin use for cardiovascular disease associated with risk of prostate cancer? Prostate 74: 97–102.

Zhang H, Qian DZ, Tan YS, Lee K, Gao P, Ren YR, Rey S, Hammers H, Chang D, Pili R, Dang CV, Liu JO, Semenza GL (2008) Digoxin and other cardiac glycosides inhibit HIF-1alpha synthesis and block tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 19579–19586.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grant (grant number 150617) from the Pirkanmaa Hospital District to TJ Murtola. We thank Erkki Karttunen for proofreading this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TJ Murtola: lecture fee from Janssen-Cilag and MSD; K Taari: lecture fee GSK, paid consultancy for Abbvie, employee of Medivation, participation in the International Meeting with sponsors Astellas and Orion; TLJ Tammela: paid consultant for Astellas, GSK, Pfizer, Orion and Amgen; A Auvinen: lecture fee from MSD, paid consultancy for Epid Research. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kaapu, K., Murtola, T., Talala, K. et al. Digoxin and prostate cancer survival in the Finnish Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer. Br J Cancer 115, 1289–1295 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.328

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.328