Abstract

Background:

Some previous studies have reported that survivors of childhood cancer are at an increased risk of developing long-term mental health morbidity, whilst others have reported that this is not the case. Therefore, we analysed 5-year survivors of childhood cancer using the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (BCCSS) to determine the risks of aspects of long-term mental health dysfunction.

Procedure:

Within the BCCSS, 10 488 survivors completed a questionnaire that ascertained mental health-related information via 10 questions from the Short Form-36 survey. Internal analyses were conducted using multivariable logistic regression to determine risk factors for mental health dysfunction. External analyses were undertaken using direct standardisation to compare mental health dysfunction in survivors with UK norms.

Results:

This study has shown that overall, childhood cancer survivors had a significantly higher prevalence of mental health dysfunction for 6/10 questions analysed compared to UK norms. Central nervous system (CNS) and bone sarcoma survivors reported the greatest dysfunction, compared to expected, with significant excess dysfunction in 10 and 6 questions, respectively; the excess ranged from 4.4–22.3% in CNS survivors and 6.9–15.9% in bone sarcoma survivors. Compared to expected, excess mental health dysfunction increased with attained age; this increase was greatest for reporting ‘limitations in social activities due to health’, where the excess rose from 4.5% to 12.8% in those aged 16–24 and 45+, respectively. Within the internal analyses, higher levels of educational attainment and socio-economic classification were protective against mental health dysfunction.

Conclusions:

Based upon the findings of this large population-based study, childhood cancer survivors report significantly higher levels of mental health dysfunction than those in the general population, where deficits were observed particularly among CNS and bone sarcoma survivors. Limitations were also observed to increase with age, and thus it is important to emphasise the need for mental health evaluation and services across the entire lifespan. There is evidence that low educational attainment and being unemployed or having never worked adversely impacts long-term mental health. These findings provide an evidence base for risk stratification and planning interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Although 5-year survival from childhood cancer has risen substantially to ∼80% (Stiller, 2007), long-term survival is accompanied by an excess risk of adverse outcomes due to late effects of the cancer and its treatment. Consequently, as the number of survivors increases, it becomes ever more important to investigate the risk of such adverse effects to identify vulnerable subgroups. While previous studies have investigated health status among childhood cancer survivors, mental health sequelae remains a concern as psychological limitations or distress have been reported in both adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer (Schultz et al, 2007; Gurney et al, 2009; Zeltzer et al, 2009; Gianinazzi et al, 2013). Additionally, conflicting findings on mental health have been reported (Reulen et al, 2007; Zeltzer et al, 2009). By identifying survivors at risk for mental health dysfunction, appropriate monitoring and early interventions within long-term care can be undertaken through risk stratification to ensure that young people and adults achieve the best possible outcomes in terms of health and social welfare, whilst optimising the expenditure of limited resources.

The goal of this study was to investigate specific aspects of mental health dysfunction among childhood cancer survivors diagnosed between the age of 0–14 years within the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (BCCSS) by assessing responses to specific questions within the Short Form-36 (SF-36) survey. Although studies have assessed aspects of mental health using this survey previously (Recklitis et al, 2003; Pemberger et al, 2005; Maunsell et al, 2006; Reulen et al, 2007; Zeltzer et al, 2008; Zeltzer et al, 2009), this is the first study to our knowledge to comprehensively analyse the 10 questions comprising the role emotional, social functioning, and mental health scales, which have been shown to be the most valid among the scales as mental health measures (Ware et al, 1993; Ware, 2000). By looking at specific questions, one can better determine the effect of various aspects of mental health dysfunction, which may have been previously undetected in a composite score or individual scale. The potential impact of demographic, cancer, social, and economic explanatory factors on mental health were explored and external analyses comparing survivors to general population norms were conducted. In doing so, this large, population-based study provides further evidence on mental health morbidity among childhood cancer survivors, which may have important implications for clinicians, family members, and survivors with regard to minimising mental health adverse late effects.

Materials and methods

Study population

The BCCSS is a population-based cohort of 17 980 individuals diagnosed with cancer before the age of 15, between 1940–1991 in Great Britain, and who have survived at least 5 years (Hawkins et al, 2008). The cohort was ascertained through the National Registry of Childhood Tumours, which has a high estimated level of completeness (∼99%) (Kroll et al, 2011). Ethical approval for the study was obtained from a Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee and every Local Research Ethics Committee in Britain (N=212 in total).

Short Form-36 survey

It was important to measure both health and social impacts on quality of life to understand the effect of childhood cancer treatment on long-term mental health. To ascertain health and social outcomes, a questionnaire was sent to all survivors in the BCCSS cohort who were alive and aged at least 16 years at questionnaire send-out (questionnaire return date range: 2001–2007, questionnaire return date median: 2002). Of the 14 836 survivors who were eligible to receive the questionnaire, 10 488 (70.7%) completed the survey (Hawkins et al, 2008). Included in the questionnaire was the SF-36, which is a generic health survey that contains 36 questions, which measure 8 dimensions of health status. From our previous work, which studied the psychometric properties of the SF-36 in the BCCSS population, we know that this survey exhibits good validity and reliability when used in long-term survivors of childhood cancer (Reulen et al, 2006).

Using the available information from the SF-36, we assessed specific aspects of mental health dysfunction, henceforth only referred to as mental health dysfunction, by looking at the 10 individual questions that comprise the role emotional, social functioning, and mental health scales (Ware et al, 1993; Ware, 2000). To assess mental health dysfunction from the responses to each question, we dichotomised the responses (Figure 1). For the mental health scale (questions 9b, 9c, 9d, 9f, and 9h) and one question relating to social functioning (question 9j), we dichotomised the responses based on whether the sentence was positively or negatively worded, where survivors were considered to be reporting dysfunction if they answered ‘all’, ‘most’, ‘a good bit’, or ‘some’ of the time to the negatively worded questions and ‘some’, ‘a little’, or ‘none of the time’ to the positively worded questions. The second social functioning question (question 6), which assessed physical or emotional interference in normal social activities, was dichotomised by categorising responses of ‘not at all’ or ‘slightly’ as not reporting dysfunction and responses of ‘moderately’, ‘quite a bit’, or ‘extremely’ as reporting dysfunction. For the role-emotional scale (questions 5a, 5b, and 5c), survivors who reported ‘yes’ were considered to be reporting mental health dysfunction. These dichotomised groupings were used to avoid the problems associated with having almost all survivors occupying one level of the dichotomy for responses to any question.

Comparison group

To compare responses to the 10 questions between survivors and the general population, the SF-36 responses from the Oxford Healthy Life Survey (OHLS) served as the reference general population sample (Jenkinson et al, 1993; Jenkinson, 1996). The OHLS was conducted between 1991 and 1992 and included 13 042 individuals aged 18–64 who were randomly sampled from the Family Health Services Authority registers for Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire. The OHLS sample resembles the UK general population with regard to socio-demographic characteristics (Jenkinson, 1996) and thus serves as an appropriate general population sample. Furthermore, the OHLS used identical questions and the same standardised method for self completion as the BCCSS questionnaire; when the characteristics of the OHLS were previously compared with BCCSS survivors only slight differences were observed in regards to sex and age (Reulen et al, 2007). The OHLS responses to the SF-36 were dichotomised as described above so that responses from survivors and the general population sample were treated identically.

Statistical analyses–internal comparison

Internal analyses, using multivariable logistic regression, were conducted to determine risk factors for mental health dysfunction among 5-year childhood cancer survivors within each of the 10 questions. All models adjusted for the following factors: age at diagnosis, sex, first primary neoplasm (FPN) diagnosis, age at questionnaire completion, marital status, socio-economic classification, and educational attainment. We decided a priori to use leukaemia survivors as the referent group because previously published literature on health status has been conducted in this manner (Hudson et al, 2003). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Likelihood ratio tests were used to assess the significance of fitted models and trends.

Statistical analyses–external comparison

To compare the prevalence of mental health dysfunction between survivors and the general population, external analyses were completed using direct (age and sex) standardisation, which would address any small differences in the characteristics between the BCCSS and OHLS. For these analyses, the general population sample acted as the reference group and survivors were compared overall and separately by FPN diagnosis and attained age. Prevalence of mental health dysfunction was reported as percentages with corresponding 95% CIs.

All analyses were undertaken using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value <0.05.

Results

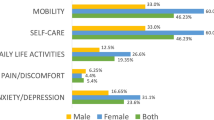

Survivors who were female, treated for a FPN of a central nervous system (CNS) tumour, unemployed or having never worked, or educationally unqualified were found to consistently report the highest prevalence of dysfunction across all 10 questions (Supplementary Table 1). Survivors who were separated, divorced, or widowed also generally reported more dysfunction than those who were single, cohabiting, or married. Mental health dysfunction within the 10 questions did not appear to differ substantially by age at diagnosis, treatment modalities (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery), or age at questionnaire completion.

Internal comparison

Risk factors associated with reporting mental health dysfunction within the role-emotional scale

Table 1 presents the multivariable models for the three mental health questions within the role-emotional scale. Females were significantly more likely to be limited in all three questions (all P<0.0001). Across FPN diagnoses there were statistically significant heterogeneity for all three questions where, compared with leukaemia survivors, survivors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), CNS tumours, and bone sarcoma were significantly more likely to be limited for all questions (all P<0.05). Also, compared with leukaemia survivors, heritable retinoblastoma survivors reported significantly more mental health dysfunction in having to ‘cut down on the amount of time you spent on work or other activities’ (OR: 1.7(1.1–2.4)) and in having ‘accomplished less than you would like’ (OR: 1.7(1.2–2.3)), whereas Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) survivors reported significantly more dysfunction in having ‘did work or other activities less carefully than usual’ (OR: 1.4(1.0–1.8)). Compared with individuals aged 16–24 at questionnaire completion, the risk for reporting mental health dysfunction in all three questions increased linearly with age (all Ptrend<0.01). An analysis by marital status showed for all three questions that, relative to single survivors, those who were separated were most at risk of reporting dysfunction, whereas those who were married were significantly less likely to report dysfunction. An association was found for educational attainment, where increased qualifications were associated with decreased odds of reporting dysfunction in all three questions. For all three questions, relative to students, survivors who had never worked or were unemployed were significantly more likely to report mental health dysfunction, whereas those who were in managerial or professional positions were significantly less likely to report dysfunction.

Risk factors associated with reporting mental health dysfunction within the social functioning scale

In the multivariable models assessing the two questions within the social functioning scale, females were again significantly more likely to report dysfunction compared to males (Table 2). An analysis by FPN diagnosis showed that compared with those diagnosed with leukaemia, CNS (OR: 1.6(1.4–1.9)), neuroblastoma (OR: 1.5(1.1–2.0)), bone sarcoma (OR: 2.0(1.5–2.7)), and soft tissue sarcoma (OR: 1.3(1.0–1.7)) survivors were all significantly more likely to report mental health dysfunction in ‘has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your normal social activities.’ NHL, CNS, neuroblastoma, heritable retinoblastoma, bone sarcoma, and soft tissue sarcoma survivors also reported significantly higher dysfunction in ‘has your health limited your social activities’, compared with leukaemia survivors, with bone sarcoma (OR: 3.0(2.3–4.0)) and CNS survivors (OR: 2.5(2.1–2.9)) being the most limited. Age at questionnaire completion was significantly associated with reporting dysfunction in both questions where those aged 25–34, 35–44, and 45+ reported more dysfunction compared with those aged 16–24 (both Ptrend<0.0001). Relative to single survivors, married survivors were significantly less likely to report dysfunction in either question (both P<0.001); no significant difference was found between single survivors and those who were cohabiting, separated, divorced, or widowed. An analysis by educational attainment showed that, compared with survivors with no qualifications, the odds of reporting mental health dysfunction decreased with higher levels of qualifications for both questions. Socio-economic classification was also found to be significantly related to reporting dysfunction in both questions where, compared with students, those who never worked or were unemployed were significantly more likely to report dysfunction (both P<0.001) and those in managerial or professional positions were significantly less likely to report dysfunction (both P⩽0.001).

Risk factors associated with reporting mental health dysfunction within the mental health scale

Survivors who were female or who had never worked or were unemployed were significantly more likely to report mental health dysfunction in all five questions within in the mental health scale relative to males and students, respectively, (Table 3). Conversely, survivors who achieved an O-level, A-level, teaching qualification, or degree were significantly less likely to report dysfunction in all questions compared with students. Age at questionnaire completion was also found to be significantly associated with reporting dysfunction in 4/5 questions, but a consistent trend was not observed within the subgroups compared with those aged 16–24. When analysed by marital status, survivors who were married were found to report significantly less mental health dysfunction in 4/5 of the questions, compared with those who were single. Survivors who were cohabiting also reported significantly less mental health dysfunction for the question relating to having ‘been a very nervous person’ (OR: 0.8(0.7–1.0)). Survivors who were separated, conversely, reported a 70% increase in mental health dysfunction compared with single survivors (OR: 1.7(1.2–2.4)). When asked if the survivor had ‘been a very nervous person’, those diagnosed with CNS (OR: 1.3(1.1–1.5)), compared with leukaemia, were significantly more likely to agree with this statement. Furthermore, in the multivariable model assessing whether survivors had ‘been a happy person’, an analysis by FPN diagnosis showed that HL (OR: 1.3(1.0–1.6)), NHL (OR: 1.4(1.1–1.8)), CNS (OR: 1.4(1.2–1.6)), neuroblastoma (OR: 1.3(1.0–1.7)), non-heritable retinoblastoma (OR: 1.4(1.0–1.8)), and bone sarcoma (OR: 1.5(1.1–1.9)) survivors reported significantly higher dysfunction compared with leukaemia survivors.

External comparison

Compared with the general population sample, survivors overall reported more mental health dysfunction in 6/10 questions that were examined (Table 4). When further assessed by FPN diagnosis, CNS and bone sarcoma survivors were found to report the greatest dysfunction, compared with that expected, with significant differences in 10 and 6 questions, respectively; the excess of dysfunction ranged from 4.4–22.3% in CNS survivors, whereas bone sarcoma survivors were limited from 6.9–15.9%. Both diagnostic groups were most disadvantaged by their health limiting their social activities. Conversely, survivors of neuroblastoma, heritable retinoblastoma, non-heritable retinoblastoma, Wilms, and other (those that did not conform to one of the 10 FPN groups used) were not significantly different in any of the questions analysed when compared with the general population sample.

An analysis by age at questionnaire completion showed that the prevalence of mental health dysfunction was comparable or better for 7/10 questions among survivors aged 16–24, compared with that expected from the general population sample (Table 5); survivors in this age group did however report a higher prevalence of having ‘been a nervous person’ (30.7% vs 23.7% expected), ‘felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up’ (25.3% vs 21.2% expected), and in ‘has your health limited your social activities’ (15.7% vs 11.2% expected). Among those aged 25–34 and 35–44 at questionnaire completion, significantly higher mental health dysfunction was reported, compared with the general population sample, in relation to six questions (questions 5a, 6, 9b, 9c, 9f, and 9j). Similarly, survivors aged 45 and older reported significantly higher dysfunction in five questions compared with that expected. Notably, the per cent difference in mental health dysfunction between survivors and the general population increased with age at questionnaire completion for both questions from the social functioning scale and the question ‘have you felt downhearted and blue’; this increase was most noticeable in the question ‘has your health limited your social activities,' where the excess rose from 4.5% to 12.8% in those aged 16–24 and 45+, respectively. Statistically significant variation in the excess by age at questionnaire completion was not observed in four questions, which related to problems with work or daily activities and feeling calm, peaceful, or happy.

Discussion

The findings from this large population-based study indicate that the prevalence of mental health dysfunction among survivors of childhood cancer in the BCCSS was substantially higher than that expected from the general population sample in over half of the questions assessed, with survivors of CNS and bone sarcoma being the most vulnerable; these findings are generally consistent with other studies that have used the SF-36 (Maunsell et al, 2006) or similar psychological measures (Hudson et al, 2003; Zebrack et al, 2004; Zeltzer et al, 2009), although some studies have suggested that mental health status was similar between survivors and comparative populations (Reulen et al, 2007; Zeltzer et al, 2009; Phipps et al, 2014). While the North American Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) found significantly higher limitations in the role emotional and social functioning scales for survivors overall, survivors of CNS and bone sarcoma were reported as having significantly less problems on the mental health scale compared to that expected from the US population reference (Zeltzer et al, 2008); this finding does not correspond with our results as CNS and bone sarcoma survivors were found to be significantly more limited in 5/5 and 3/5 of the questions that comprise the mental health scale, respectively. The same study (Zeltzer et al, 2008) also reported significantly higher limitations in regards to the role emotional and social functioning scales for HL, NHL, Wilms, and neuroblastoma survivors, compared with US norms, which conflicts with the results presented in this study as these survivors were not significantly more limited in any of the questions comprising these scales compared with the general population sample. Although the CCSS and this study used different methodologies, with the CCSS using means and this study using proportions when assessing differences between childhood cancer survivors and general population norms, broad patterns of agreement in the findings from the CCSS and this study are expected as both studies adjusted for sex and age. These inconsistencies with our study might reflect differences in study demographics, cohort design, or therapeutic practice between North America and Great Britain.

Another important finding in this study was that, although younger survivors (16–24 years) perceived their mental health as broadly similar to the general population, significant mental health dysfunction was reported in at least half of the questions among those aged 25 years and older. A particular concern was found among the questions relating to social functioning as significant mental health dysfunction was reported for all age groups. Furthermore, the extent of the excess among survivors increased with age at questionnaire completion for both questions within the social functioning scale. This finding corresponds with another study that reported significantly more disadvantage in the social functioning scale in those assessed 10–14 and 15–19 years from diagnosis compared to a control group (Maunsell et al, 2006). A possible explanation as to why mental health dysfunction increased with age may be due to the fact that the risk of complex and multiple late effects emerging increases as time since treatment increases (Oeffinger et al, 2006; Geenen et al, 2007; Hudson et al, 2013; Armstrong et al, 2014). Although late effects may not immediately affect survivors, they may become more important with maturity and influence life decisions and experiences later on. For example, infertility may become a greater concern and impact mental health when survivors want to start a family. Living with chronic health conditions, such as infertility, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, blindness, physical disability, and epilepsy, which can often be managed but not cured, may have long-term consequences on both physical and psychological health, stressing the importance for life course care and services.

The internal analyses similarly revealed that CNS and bone sarcoma survivors reported higher levels of mental health dysfunction compared to other types of childhood cancer, with CNS survivors being limited in all questions assessed and bone sarcoma survivors being limited in all questions relating to the social functioning and role-emotional scales. Broadly, this finding conflicts with an analysis by the CCSS, which found no significant difference among childhood cancer survivors by FPN diagnosis (Hudson et al, 2003); however, it is worth noting that in the CCSS the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 survey was used and thus results are not directly comparable. Other risk factors for mental health dysfunction included being female, separated from a spouse/partner, and unemployed or having never worked, which corresponds with previous reports using the SF-36 (Zeltzer et al, 2008; Zeltzer et al, 2009) or similar measures to predict psychological distress (Hudson et al, 2003). Low educational attainment, unemployment, and other socio-economic disadvantages are recognised risks to mental health in the general population (Marmot, 2010). However, the effects of these determinants may be even more detrimental among childhood cancer survivors as these individuals, when assessed with comparative norms, experience an even greater risk of morbidity and adverse psychosocial outcomes (Mitby et al, 2003; de Boer et al, 2006; Oeffinger et al, 2006; Frobisher et al, 2007; Geenen et al, 2007; Pang et al, 2008; Lancashire et al, 2010; Hudson et al, 2013; Armstrong et al, 2014). Conversely, survivors who received some educational qualifications or worked in a managerial/professional position were found to exhibit less mental health dysfunction compared with their respective referents, which also generally corresponds with previous reports (Zeltzer et al, 2008).

Limitations

Response bias due to selective responses should be minimal due to our reasonably good response rate and the fact that there was not a substantial difference in cancer and socio-demographic characteristics between responders and non-responders of our questionnaire (Reulen et al, 2007). There is potentially selection bias due to survival, particularly among the group of older survivors as they may be healthier than their counterparts who did not survive until questionnaire send-out. Another limitation in our study is our comparison data, which may differ from our study population in terms of socio-economic status. However, as the results from our internal and external analyses broadly correspond with one another, confounding by this factor should be limited. Another limitation of this study is the lack of detailed treatment information, which precluded any analyses being completed by clinically relevant radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgery categories. However, in our analyses we have included FPN diagnosis, which can serve as a proxy for treatment and still offer meaningful clinical importance. In addition, this study has only assessed self-reported mental health dysfunction. Although we do not identify the risk of extreme mental health impairment (i.e., through psychiatric admissions in hospitalisation registries), the purpose of this study was to quantify daily mental health morbidities for all individuals included in the study and assess in more detail the degree of limitation in specific questions of mental health. Finally, although the findings from this paper may not be generalisable for children diagnosed with cancer after 1991, they are still highly relevant to children treated more recently for whom treatment intensity and long-term morbidity may be greater. We acknowledge reassessment is necessary and recommend further analyses to be conducted on the recently extended BCCSS cohort, which includes 5-year survivors diagnosed from 1992–2006, and other long-term follow-up studies.

Clinical recommendations

Although the need for long-term psychological assessment and care is recognised (Chang, 1991; Eiser et al, 2000; Wallace et al, 2001; Zeltzer et al, 2009), there remain uncertainties as to how these individuals should be assessed. A previous study reported that approximately only 35% of childhood cancer survivors in the UK were on hospital follow-up (Taylor et al, 2004). Consequently, as general practitioners provide health care for the majority of these survivors (Oeffinger, 2004), routine psychological assessment, preferably using a standardised and validated measure, should be integrated into both long-term hospital follow-up clinics and general practitioner visits, especially for the vulnerable subgroup of survivors identified in this study. To date, psychological provisions are lacking in late effects services and are rare in the primary care setting. To improve mental health, it is essential that recommendations for risk-based care are readily available for general practitioners and ongoing communication is coordinated across all sites and services involved. Furthermore, surveillance for mental health dysfunction and recommended interventions should be included in the development of clinical guidelines, treatment summaries, and patient care plans. As the results from this study suggest mental health dysfunction is a concern across the lifespan for survivors, it is imperative that equitable psychological support is continuously available within general practices or specialist late effects services, irrespective of the amount of time that has passed since initial diagnosis, and that funding is allocated to allow for interventions. Finally, the findings presented in this study also stress the importance of educational attainment and employment on long-term mental health. Educational support and career advisors should be provided during and after treatment to ensure that childhood cancer survivors achieve their full educational and employment potential and have the same likelihood of academic and professional success as their peers. By continually improving the standard of care for mental health in childhood cancer survivors, we work towards meeting the goal of psychosocial oncology research, which is to facilitate patients’ adjustment to the short- and long-term consequences of their treatment, recovery, and survivorship so that quality of life is not reduced (Holland et al, 1998).

Conclusion

Based upon the findings of this large population-based study, childhood cancer survivors report significantly higher levels of mental health dysfunction than those in the general population, where excesses were observed particularly among CNS and bone sarcoma survivors. Limitations were also observed to increase with age, and thus it is important to emphasise the need for mental health evaluation and services across the entire lifespan. There is evidence that low educational attainment and being unemployed or having never worked adversely impacts long-term mental health. These findings provide an evidence base for risk stratification and planning interventions.

References

Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, Stratton K, Stovall M, Hudson MM, Sklar CA, Robison LL, Oeffinger KC (2014) Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 32 (12): 1218–1227.

Chang PN (1991) Psychosocial needs of long-term childhood cancer survivors: a review of literature. Pediatrician 18 (1): 20–24.

de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, van Dijk FJ (2006) Adult survivors of childhood cancer and unemployment: a metaanalysis. Cancer 107 (1): 1–11.

Eiser C, Hill JJ, Vance YH (2000) Examining the psychological consequences of surviving childhood cancer: systematic review as a research method in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol 25 (6): 449–460.

Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Jenkinson HC, Hawkins MM (2007) Long-term population-based marriage rates among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Britain. Int J Cancer 121 (4): 846–855.

Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, van den Bos C, van der Pal HJ, Heinen RC, Jaspers MW, Koning CC, Oldenburger F, Langeveld NE, Hart AA, Bakker PJ, Caron HN, van Leeuwen FE (2007) Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 297 (24): 2705–2715.

Gianinazzi ME, Rueegg CS, Wengenroth L, Bergstraesser E, Rischewski J, Ammann RA, Kuehni CE, Michel G for Swiss Pediatric Oncology G (2013) Adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: are they vulnerable for psychological distress? Psychooncology 22 (9): 2051–2058.

Gurney JG, Krull KR, Kadan-Lottick N, Nicholson HS, Nathan PC, Zebrack B, Tersak JM, Ness KK (2009) Social outcomes in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J Clin Oncol 27 (14): 2390–2395.

Hawkins MM, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Reulen RC, Taylor AJ, Stevens MC, Jenney M (2008) The British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: objectives, methods, population structure, response rates and initial descriptive information. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50 (5): 1018–1025.

Holland JC, Kash KM, Passik S, Gronert MK, Sison A, Lederberg M, Russak SM, Baider L, Fox B (1998) A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psychooncology 7 (6): 460–469.

Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Hobbie W, Chen H, Gurney JG, Yeazel M, Recklitis CJ, Marina N, Robison LR, Oeffinger KC Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Investigators (2003) Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 290 (12): 1583–1592.

Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, Mulrooney DA, Chemaitilly W, Krull KR, Green DM, Armstrong GT, Nottage KA, Jones KE, Sklar CA, Srivastava DK, Robison LL (2013) Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA 309 (22): 2371–2381.

Jenkinson C (1996) The UK. SF-36: an Analysis and Interpretation Manual. Health Services Research Unit: London.

Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L (1993) Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. Br Med J 306: 1437–1440.

Kroll ME, Murphy MF, Carpenter LM, Stiller CA (2011) Childhood cancer registration in Britain: capture-recapture estimates of completeness of ascertainment. Br J Cancer 104 (7): 1227–1233.

Lancashire ER, Frobisher C, Reulen RC, Winter DL, Glaser A, Hawkins MM (2010) Educational attainment among adult survivors of childhood cancer in Great Britain: a population-based cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (4): 254–270.

Marmot M (2010) Fair Society. Strategic review of health inequalities in england post-2010: the marmot review.

Maunsell E, Pogany L, Barrera M, Shaw AK, Speechley KN (2006) Quality of life among long-term adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 24 (16): 2527–2535.

Mitby PA, Robison LL, Whitton JA, Zevon MA, Gibbs IC, Tersak JM, Meadows AT, Stovall M, Zeltzer LK, Mertens AC (2003) Utilization of special education services and educational attainment among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 97 (4): 1115–1126.

Oeffinger KC (2004) Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med 2 (1): 61–70.

Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Marina N, Hobbie W, Kadan-Lottick NS, Schwartz CL, Leisenring W, Robison LL (2006) Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355 (15): 1572–1582.

Pang JW, Friedman DL, Whitton JA, Stovall M, Mertens AC, Robison LL, Weiss NS (2008) Employment status among adult survivors in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50 (1): 104–110.

Pemberger S, Jagsch R, Frey E, Felder-Puig R, Gadner H, Kryspin-Exner I, Topf R (2005) Quality of life in long-term childhood cancer survivors and the relation of late effects and subjective well-being. Support Care Cancer 13 (1): 49–56.

Phipps S, Klosky JL, Long A, Hudson MM, Huang Q, Zhang H, Noll RB (2014) Posttraumatic stress and psychological growth in children with cancer: has the traumatic impact of cancer been overestimated? J Clin Oncol.

Recklitis C, O’Leary T, Diller L (2003) Utility of routine psychological screening in the childhood cancer survivor clinic. J Clin Oncol 21 (5): 787–792.

Reulen RC, Winter DL, Lancashire ER, Zeegers MP, Jenney ME, Walters SJ, Jenkinson C, Hawkins MM (2007) Health-status of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a large-scale population-based study from the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Int J Cancer 121 (3): 633–640.

Reulen RC, Zeegers MP, Jenkinson C, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Jenney ME, Hawkins MM (2006) The use of the SF-36 questionnaire in adult survivors of childhood cancer: evaluation of data quality, score reliability, and scaling assumptions. Health Qual Life Outcomes 4: 77.

Schultz KA, Ness KK, Whitton J, Recklitis C, Zebrack B, Robison LL, Zeltzer L, Mertens AC (2007) Behavioral and social outcomes in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 25 (24): 3649–3656.

Stiller C (2007) Childhood Cancer in Britain: Incidence, Survival and Mortality. Oxford Unviersity Press.

Taylor A, Hawkins M, Griffiths A, Davies H, Douglas C, Jenney M, Wallace WHB, Levitt G (2004) Long-term follow-up of survivors of childhood cancer in the UK. Pediatr Blood Cancer 42 (2): 161–168.

Wallace WH, Blacklay A, Eiser C, Davies H, Hawkins M, Levitt GA, Jenney ME (2001) Developing strategies for long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer. BMJ 323 (7307): 271–274.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B (1993) SF-36 Heath Survey: Manuel and Interpretation Guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center: Boston, Massachusetts.

Ware JEJ (2000) SF-36 health survey update. Spine 25 (24): 3130–3139.

Zebrack BJ, Gurney JG, Oeffinger K, Whitton J, Packer RJ, Mertens A, Turk N, Castleberry R, Dreyer Z, Robison LL, Zeltzer LK (2004) Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood brain cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 22 (6): 999–1006.

Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, Tsao JC, Recklitis C, Armstrong G, Mertens AC, Robison LL, Ness KK (2008) Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 17 (2): 435–446.

Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, Zebrack B, Casillas J, Tsao JC, Lu Q, Krull K (2009) Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27 (14): 2396–2404.

Acknowledgements

The BCCSS is a national collaborative undertaking guided by a Steering Group that comprises Professor Douglas Easton (chair), Professor Michael Hawkins, Dr Helen Jenkinson, Dr Meriel Jenney, Dr Raoul Reulen, Professor Kathryn Pritchard-Jones, Professor Michael Stevens, Dr Elaine Sugden, Dr Andrew Toogood, and Dr Hamish Wallace. The BCCSS benefits from the contributions of the Officers, Centers, and individual members of the Children’s Cancer and Leukemia Group and the Regional Pediatric Cancer Registries. The BCCSS acknowledges the collaboration of the Office for National Statistics, the General Register Office for Scotland, the Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unit, the National Health Service Information Centre, the regional cancer registries, health authorities, and area health boards for providing general practitioner names and addresses and the general practitioners nationwide who facilitated direct contact with survivors. We are particularly thankful to all survivors who completed a 40-page questionnaire and all General Practitioners who returned consent forms. The BCCSS would not have been possible without the support of our funders: University of Birmingham, Cancer Research UK, the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund, and the European Commission to whom we offer our profound thanks. Finally thanks to all BCCSS staff who have given many years of dedicated work to bring the BCCSS to fruition. This work was supported by grant number C386/A10422 from Cancer Research UK; the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund; PanCareSurFup, European 7th Framework Programme. Raoul C. Reulen is funded by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Fidler, M., Ziff, O., Wang, S. et al. Aspects of mental health dysfunction among survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer 113, 1121–1132 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.310

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.310

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Support needs of Dutch young adult childhood cancer survivors

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Psychosocial developmental milestones of young adult survivors of childhood cancer

Supportive Care in Cancer (2022)

-

Childhood cancer survivorship care during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international report of practice implications and provider concerns

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2022)

-

A vulnerable age group: the impact of cancer on the psychosocial well-being of young adult childhood cancer survivors

Supportive Care in Cancer (2021)

-

Hospitalization and mortality among pediatric cancer survivors: a population-based study

Cancer Causes & Control (2018)