Abstract

Background:

Radical hysterectomy is recommended for endometrial adenocarcinoma patients with suspected gross cervical involvement. However, the efficacy of operative procedure has not been confirmed.

Methods:

The patients with endometrial adenocarcinoma who had suspected gross cervical involvement and underwent hysterectomy between 1995 and 2009 at seven institutions were retrospectively analysed (Gynecologic Oncology Trial and Investigation Consortium of North Kanto: GOTIC-005). Primary endpoint was overall survival, and secondary endpoints were progression-free survival and adverse effects.

Results:

A total of 300 patients who underwent primary surgery were identified: 74 cases with radical hysterectomy (RH), 112 patients with modified radical hysterectomy (mRH), and 114 cases with simple hysterectomy (SH). Median age was 47 years, and median duration of follow-up was 47 months. There were no significant differences of age, performance status, body mass index, stage distribution, and adjuvant therapy among three groups. Multi-regression analysis revealed that age, grade, peritoneal cytology status, and lymph node involvement were identified as prognostic factors for OS; however, type of hysterectomy was not selected as independent prognostic factor for local recurrence-free survival, PFS, and OS. Additionally, patients treated with RH had longer operative time, higher rates of blood transfusion and severe urinary tract dysfunction.

Conclusion:

Type of hysterectomy was not identified as a prognostic factor in endometrial cancer patients with suspected gross cervical involvement. Perioperative and late adverse events were more frequent in patients treated with RH. The present study could not find any survival benefit from RH for endometrial cancer patients with suspected gross cervical involvement. Surgical treatment in these patients should be further evaluated in prospective clinical studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Endometrial cancer is the most frequently occurring gynaecologic cancer in the United States and Europe (Evans et al, 2011; Siegel et al, 2012). The most common histology is endometrioid-type and the majority of the tumours are confined to the uterine corpus. The 1988 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging defined stage II disease as pathological involvement of the uterine cervix. At the time, stage II disease was subclassified as glandular involvement alone (IIA) or stromal invasion (IIB). Estimated 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of surgical stage II disease was ∼85% (Cornelison et al, 1999; Ayhan et al, 2004; Cohn et al, 2007). However, there have been several factors affecting the prognosis of stage II patients, such as cervical stromal invasion, lymph-vascular invasion, and high grade histology.

Recently, the presence of glandular involvement only was not included in stage II disease (Creasman, 2009), as the prognosis of stage IIA patients was not relatively worse. Radical hysterectomy was recommended for patients with suspected gross cervical involvement (Nagase et al, 2010; NCCN Guidelines, 2013). However, it is still undetermined which type of hysterectomy should be undertaken for the patients with stage II endometrial cancers. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of operative procedure for endometrial cancers within the largest series of the cases using multivariate analyses.

Materials and methods

Patients and tumours

Institutional review board approval was obtained at seven academic institutions belonging to Gynecologic Oncology Trial and Investigation Consortium of North Kanto (GOTIC): National defense medical college, the University of Tsukuba, the Jichi medical University, Saitama cancer centre, Saitama Shakaihoken hospital, the Gunma University, Saitama medical University International Medical centre.

Medical charts of the patients who met the criteria as shown below were retrospectively analysed: (a) endometrial cancer patients that were treated during the period of 1995–2009, (b) patients that had suspected pathological cervical involvement by MR images or cervical biopsy, (c) extra-uterine disease was not detected by preoperative CT or MRI images. Only patients who received primary surgical therapy were included. Clinical data abstracted included type of surgery, complication related with surgery, adjuvant therapy, and follow-up data including recurrent site and patient status at the last visit.

Pathologic data such as FIGO stage, histologic type, tumour grade, depth of myometrial invasion, cervical stromal invasion, lymph-vascular invasion, and retroperitoneal lymph node involvement were also analysed. A formal review of the pathologic material was performed by at least one pathologist in each institution. Confirmation of cervical invasion and staging was made by the review of these pathologic reports. Patients with carcinosarcoma, or endometrial stromal sarcoma were not included in the present analysis.

Procedures of hysterectomy

All surgeries were performed or supervised by board-certified gynaecologic oncologists. Type of hysterectomy was based on the definition made by Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) as shown below (Nagase et al, 2010).

Simple hysterectomy (SH): uterine support structures and vaginal canals are severed near the uterine attachment site. This is an extrafascial technique that removes some vaginal wall so that there is no residual cervical area.

Modified radical hysterectomy (mRH): The anterior layer of the vesicouterine ligament is separated and resected. The ureters are avoided and displaced laterally, and the uterus is resected by dividing as much as possible the anterior support and vaginal wall from the cervix. However, the posterior layer of the vesiocouterine ligament is not separated or severed. An extra 1.5–2 cm of vaginal wall can therefore be removed. Another characteristic of this technique is that more of the cardinal ligament is resected than in a SH. Extended total hysterectomy is used synonymously with mRH.

Radical hysterectomy (RH): the paravesical space and pararectal space are extended, and each of the anterior, middle, and podterio uterine supports is separated and severed. Portions of the vaginal wall and pelvic connective tissue are widely excised, and a regional pelvic node dissection is performed. That is, the cardinal ligament is severed near the pelvic wall, and the anterior layer of the vesicouterine ligament is separated and severed. The ureters are detached and displaced laterally, and the posterior layer is separated and severed. The rectovaginal ligament and ligament in the rectal space are severed. The paravaginal connective tissue and a portion of the vaginal wall (at least 3 cm) are then excised.

Grading of adverse events was judged by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0.

Statistical methods

Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the date of primary surgery to the date of subsequent radiologic relapse, progression, or to the date of last contact for disease-free patients. Overall survival was defined as the period from the date of primary surgery to death or the date of last contact. Local recurrence-free time was the duration between the date of surgery and the development of local recurrence including vaginal cuf, paravaginal tissues, and pelvic lymph nodes, or to the date of last contact for local recurrence-free patients.

Kaplan–Meier method was used for calculation of patient survival distribution. The significance of the survival distribution in each group was tested by the log-rank test. The χ2 test and Student’s t-test for unpaired data were used for statistical analysis. Cox proportional hazards model was used for multivariate analysis of the survival. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Stat View software ver.5.0 (SAS Institution Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to analyse the data.

Results

A total of 300 patients were identified: 74 cases with RH, 112 patients with mRH, and 114 cases with SH. Characteristics of the patients were summarised in Table 1. Median age was 47 years, and median duration of follow-up was 47 months. There were no significant differences of age, performance status, body mass index, and stage distribution among three groups. In the patients who underwent RH, more cases were suspected to have cervical stromal involvement, and underwent lymphadenectomy. As a postoperative therapy, chemotherapy was administered in 46 cases (62%) of RH, 50 cases (45%) of mRH, and 58 patients (51%) of SH group, indicating that there was no significant difference of the rate. Also, there were no significant differences among rates that received adjuvant radiation: 14 cases (19%) of RH, 12 cases (11%) of mRH, and 17 cases (15%) of SH groups (Table 1).

Pathologic findings of the patients were shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences of histological subtype, degree of cervical involvement, and peritoneal implantation beyond pelvis among three groups. Additionally, pathological parametrial invasion was observed in 10.8% in RH, 4.4% in mRH, and 5.3% in SH; however, there was no significant difference among three groups. Significantly, more cases in patients that underwent RH had myometrial invasion more than one half of the thickness. Additionally, the involvement of lymph node was more frequently observed in the patients with RH (P<0.01).

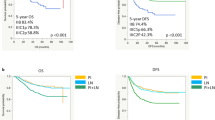

Local recurrence-free survival curves showed there were no significant differences among three groups, not only in all cases but also in patients with cervical stromal involvement (Figure 1A and B). Five-year local recurrence-free survival rates were 88.0% in RH, 89.6% in mRH, and 87.9% in SH group, respectively. Also, there was no significant difference in the patients that had pathological cervical stromal involvement among three groups.

(A) Local recurrence-free curves of all patients according to the type of hysterectomy. There was no significant difference among three groups. Five-year survival rates were 88.0% in RH, 89.6% in mRH, and 87.9% in SH group, respectively. There was no significant difference among three groups. (B) Local recurrence-free curves of the patients that had pathological cervical stromal involvement according to the type of hysterectomy. There was no significant difference in OS among three groups. Five-year survival rates were 86.4% in RH, 87.9% in mRH, and 86.5% in SH group, respectively. There was no significant difference among three groups.

There were no significant differences of PFS and OS among three operative procedures (Figure 2A and B). Five-year OS rates were 83.6% in RH, 85.6% in mRH, and 84% in SH group. Five-year progression-free survival rates were 71.6% in RH, 77.7% in mRH, and 66.4% in SH group, respectively. Moreover, OS and PFS curves of the patients with pathological stromal involvement without extra-uterine spread, which are currently categorised as FIGO stage II disease, were shown in Figure 3A and B. There were also no significant survival differences according to operative procedures. Distribution of operative procedure, estimated 5-year OS rate, and duration of follow-up in each institution was shown in Supplementary Table 1.

(A) Overall survival curves of all cases according to the type of hysterectomy. Five-year overall survival rates were 83.6% in RH, 85.6% in mRH, and 84% in SH group, respectively. There was no significant difference in OS among three groups. (B) PFS curves of all patients according to the type of hysterectomy. Five-year PFS rates were 71.6% in RH, 77.7% in mRH, and 66.4% in SH group, respectively. There was no significant difference in PFS among three groups.

(A) Overall survival curves of the patients who had pathological cervical stromal involvement only (current FIGO stage II diseases) according to the type of hysterectomy. Five-year OS rates were 89.5% in RH, 86.0% in mRH, and 92.4% in SH group, respectively. There was no significant difference in OS among three groups. (B) PFS curves of the patients who had pathological cervical stromal involvement only (current FIGO stage II diseases) according to the type of hysterectomy. Five-year PFS rates were 74.1% in RH, 80.9% in mRH, and 70.1% in SH group, respectively. There was no significant difference in PFS among three groups.

Multi-regression analysis revealed that age, grade, peritoneal cytology status, and lymph node involvement were identified as prognostic factors for OS (Table 3); however, type of hysterectomy was not selected as independent prognostic factor for local recurrence-free survival, PFS, and OS (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2).

Adverse effects according to surgical procedures were shown in Table 4. Median operative time was significantly longer in RH and mRH group compared with SH group. Amount of blood loss and rate of blood transfusion were higher in RH group. In late adverse effects, urinary retention of grade ⩾2 was more frequently observed in RH group.

Discussion

For patients with suspected or gross cervical involvement, cervical biopsy or MR images were recommended for preoperative diagnosis (Manfredi et al, 2004; Akin et al, 2007). It is sometimes difficult to distinguish primary cervical cancer from endometrial cancer with cervical involvement. Therefore, the recommendation was that RH should be considered for the cases with stage II endometrial cancers (NCCN Guidelines, 2013). The hypothesis is that RH could remove parametrial metastasis in the patients with cervical involvement, because the incidence of parametrial invasion occurred in 14% of the cases with cervical involvement (Lee et al, 2010). The present study indicated that pathological parametrial invasion was not an independent prognostic factor for not only OS, but also local recurrence-free survival. Actually, some reports implied that RH improved prognosis of endometrial cancers with cervical involvement (Mariani et al, 2001; Sartori et al, 2001); however, these results were not based on multivariate analysis. Additionally, other clinicopathologic factors, such as histological grade, degree of cervical involvement, lymph node metastasis, and myometrial invasion, affected the prognosis more strongly. Recently, a report including 1577 cases of stage II endometrial cancers revealed that RH had no effect on survival (Wright et al, 2009); however, the conclusions were not based on multivariate analyses. The present study had the largest number of stage II cases of endometrial cancers that enabled multivariate analyses and revealed that procedures of hysterectomy were not prognostic factors for local recurrence-free survival, PFS, and OS.

Additionally, RH needed significantly longer operative time, and produced more amount of blood loss, increasing the rate of blood transfusion. Although there were no significant differences of acute side effects such as thrombosis and ileus, postoperative urinary dysfunction of grade ⩾2 occurred more frequently in patients with RH. Special caution is needed to avoid urinary dysfunction, because it continued long, and severely decreased the level of quality of life.

Adjuvant radiotherapy for early-stage endometrial cancer has been mainly limited to radiation therapy (NCCN Guidelines, 2013). Pelvic radiotherapy is the backbone of adjuvant therapy for stage II endometrial cancers: vaginal brachytherapy and/or pelvic radiation for grade 1, pelvic radiotherapy+vaginal brachytherapy for grade 2, and pelvic radiotherapy+vaginal brachytherapy±chemotherapy for grade 3 tumours, respectively. The use of adjuvant chemotherapy in combination with radiotherapy was recommended for grade 3 tumours from the results of two randomized trials (Hogberg et al, 2010); however, the addition of chemotherapy was related with only improved PFS, and there was no effect on OS. In contrast, the effect of systematic chemotherapy as adjuvant therapy has been evaluated for the patients with intermediate–high risk endometrial cancers. The Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group compared pelvic radiotherapy and chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in patients with stage IC–IIIC endometrial cancer, and suggested a survival advantage of chemotherapy in the women from the high-to-intermediate risk group (stage IC, >70 years of age, grade 3, stage II, or positive cytology with >50% myometrial invasion) (Susumu et al, 2008). Moreover, The Gynecologic Oncology Group study 122 revealed that chemotherapy with doxorubicin plus cisplatin was associated with superior PFS in patients with stage III–IV endometrial cancer along with a minimal residual tumour, compared with radiation therapy (Randall et al, 2006). These results have had a significant impact on clinical practice in the Japanese gynaecologic oncology community, and adjuvant chemotherapy was often used for the endometrial cancer patients with high-to-intermediate risk group including stage II disease. The present study included a higher abundance of patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, which might be reflecting completely different preference of Japanese physicians. However, the survival data of these series were not inferior to the previous reports that investigated stage II patients (Mariani et al, 2001; Sartori et al, 2001). Chemotherapy could be potentially a candidate for adjuvant therapy for endometrial cancers with intermediate–high risk. In the present study, there were no significant differences of adjuvant therapy on survival. Of note, radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy produced lowest hazard ratio in local recurrence-free survival (HR=0.28) and OS (HR=0.35), although it did not reach statistical significance. Further analyses are needed to elucidate to select adjuvant therapy for the disease.

The limitation of the present study included a retrospective investigation and multi-institutional analysis. Also, the results obtained by the present study could potentially have a bias such as selection bias, and further prospective investigation is needed to confirm the impact of operative procedures. Nevertheless, the survival improvement was not observed by RH for endometrial cancer patients with suspected cervical involvement by multivariate analyses. The necessity of RH in these patients should be evaluated in further clinical studies.

Change history

01 October 2013

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Akin O, Mironov S, Pandit-Taskar N, Hann LE (2007) Imaging of uterine cancer. Radiol Clin North Am 45 (1): 167–182.

Ayhan A, Taskiran C, Celik C, Yuce K (2004) The long-term survival of women with surgical stage II endometrioid type endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 93 (1): 9–13.

Cohn DE, Woeste EM, Cacchio S, Zanagnolo VL, Havrilesky LJ, Mariani A, Podratz KC, Huh WK, Whitworth JM, McMeekin DS, Powell MA, Boyd E, Phillips GS, Fowler JM (2007) Clinical and pathologic correlates in surgical stage II endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 109 (5): 1062–1067.

Cornelison TL, Trimble EL, Kosary CL (1999) SEER data, corpus uteri cancer: treatment trends versus survival for FIGO stage II, 1988-1994. Gynecol Oncol 74 (3): 350–355.

Creasman W (2009) Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105 (2): 109.

Evans T, Sany O, Pearmain P, Ganesan R, Blann A, Sundar S (2011) Differential trends in the rising incidence of endometrial cancer by type: data from a UK population-based registry from 1994 to 2006. Br J Cancer 104 (9): 1505–1510.

Hogberg T, Signorelli M, de Oliveira CF, Fossati R, Lissoni AA, Sorbe B, Andersson H, Grenman S, Lundgren C, Rosenberg P, Boman K, Tholander B, Scambia G, Reed N, Cormio G, Tognon G, Clarke J, Sawicki T, Zola P, Kristensen G (2010) Sequential adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy in endometrial cancer—results from two randomised studies. Eur J Cancer 46 (13): 2422–2431.

Lee TS, Kim JW, Kim DY, Kim YT, Lee KH, Kim BG, McMeekin DS (2010) Necessity of radical hysterectomy for endometrial cancer patients with cervical invasion. J Korean Med Sci 25 (4): 552–556.

Manfredi R, Mirk P, Maresca G, Margariti PA, Testa A, Zannoni GF, Giordano D, Scambia G, Marano P (2004) Local-regional staging of endometrial carcinoma: role of MR imaging in surgical planning. Radiology 231 (2): 372–378.

Mariani A, Webb MJ, Keeney GL, Calori G, Podratz KC (2001) Role of wide/radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection in endometrial cancer with cervical involvement. Gynecol Oncol 83 (1): 72–80.

Nagase S, Katabuchi H, Hiura M, Sakuragi N, Aoki Y, Kigawa J, Saito T, Hachisuga T, Ito K, Uno T, Katsumata N, Komiyama S, Susumu N, Emoto M, Kobayashi H, Metoki H, Konishi I, Ochiai K, Mikami M, Sugiyama T, Mukai M, Sagae S, Hoshiai H, Aoki D, Ohmichi M, Yoshikawa H, Iwasaka T, Udagawa Y, Yaegashi N Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (2010) Evidence-based guidelines for treatment of uterine body neoplasm in Japan: Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) 2009 edition. Int J Clin Oncol 15 (6): 531–542.

NCCN Guidelines version 1.2013 (2013) Uterine Neoplasm, http://www.nccn.org/index.asp . Accessed on 11 April 2013.

Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, Spirtos NM, Mannel RS, Fowler J, Thigpen JT, Benda JA Gynecologic Oncology Group Study (2006) Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 24 (1): 36–44.

Sartori E, Gadducci A, Landoni F, Lissoni A, Maggino T, Zola P, Zanagnolo V (2001) Clinical behavior of 203 stage II endometrial cancer cases: the impact of primary surgical approach and of adjuvant radiation therapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 11 (6): 430–437.

Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2012) Cancer statics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 62 (1): 10–29.

Susumu N, Sagae S, Udagawa Y, Niwa K, Kuramoto H, Satoh S, Kudo R Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (2008) Randomized phase III trial of pelvic radiotherapy versus cisplatin-based combined chemotherapy in patients with intermediate- and high risk endometrial cancer: a Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 108 (1): 226–233.

Wright JD, Fiorelli J, Kansler AL, Burke WM, Schiff PB, Cohen CJ, Herzog TJ (2009) Optimizing the management of stage II endometrial cancer: the role of radical hysterectomy and radiation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200 4: 419.e1–e7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Takano, M., Ochi, H., Takei, Y. et al. Surgery for endometrial cancers with suspected cervical involvement: is radical hysterectomy needed (a GOTIC study)?. Br J Cancer 109, 1760–1765 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.521

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.521

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

What is the impact of radical hysterectomy on endometrial cancer with cervical involvement?

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2020)

-

S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie des Endometriumkarzinoms

Der Pathologe (2019)

-

Does the extension of the type of hysterectomy contribute to the local control of endometrial cancer?

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2019)

-

Operative Therapie des Endometriumkarzinoms

Der Gynäkologe (2018)

-

Operative Therapie des Endometriumkarzinoms

Der Onkologe (2017)