Abstract

Background:

It has been suggested that the apparent protective effect of alcohol intake on renal cell carcinoma may be due to the diluting effect of carcinogens by a high total fluid intake. We assessed the association between intakes of total fluids and of specific beverages on the risk of renal cell carcinoma in a large prospective cohort of UK women.

Methods:

Information on beverage consumption was obtained from a questionnaire sent ∼3 years after recruitment into the Million Women Study. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for renal cell carcinoma associated with beverage consumption adjusted for age, region of residence, socioeconomic status, smoking, and body mass index.

Results:

After an average of 5.2 years of follow-up, 588 cases of renal cell carcinoma were identified among 779 369 women. While alcohol intake was associated with a reduced risk of renal cell carcinoma (RR for ⩾2 vs <1 drink per day: 0.76; 95% CI: 0.61–0.96; P for trend=0.02), there was no association with total fluid intake (RR for ⩾12 vs <7 drinks per day: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.91–1.45; P for trend=0.3) or with intakes of specific beverages.

Conclusions:

The apparent protective effect of alcohol on the risk of renal cell carcinoma is unlikely to be related to a high fluid intake.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

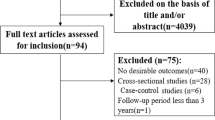

Kidney cancer is relatively rare, accounting for about 2% of cancers in women. The most important risk factors identified to date are obesity, smoking, and hypertension (Chow et al, 2000; IARC, 2004; Reeves et al, 2007). Although the role of other lifestyle factors in the aetiology of kidney cancer remain unclear, there is growing epidemiological evidence that alcohol consumption may lower the risk of renal cell carcinoma, which comprises about 80–90% of all kidney cancers. We have previously shown that, among middle-aged women in the United Kingdom, each additional alcoholic drink regularly consumed per day is associated with a significant reduction in risk of about 12% (Allen et al, 2009), and which is consistent with findings from a pooled analysis of data from 12 other prospective studies (Lee et al, 2007a). However, the mechanisms through which alcohol may reduce risk are unclear. It has been suggested that a high fluid intake, rather than alcohol consumption per se, may reduce the risk of renal cell carcinoma by increasing urine volume and thereby diluting the concentration of carcinogens within the kidney. However, only two case–control studies (Kreiger et al, 1993; Wolk et al, 1996) and one cohort study (Lee et al, 2006) have examined whether total fluid intake is associated with the risk of renal cell carcinoma.

The aim of this study is to examine the association between the consumption of total fluid and of specific beverages in relation to the risk of renal cell carcinoma in a large cohort of middle-aged women in the United Kingdom.

Materials and methods

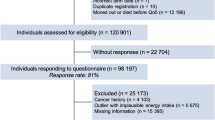

The Million Women Study has been described in detail elsewhere (Allen et al, 2009). Briefly, between 1996 and 2001 a total of 1.3 million women aged 50–64 years attending breast cancer screening clinics in the United Kingdom completed a questionnaire asking about their lifestyle and other personal factors. All women were mailed a self-administered second questionnaire, on average 3.1 (s.d., 1.9) years after recruitment, that updated information on a range of measures, including new questions on diet, based on a food-frequency questionnaire, and intakes of various types of beverages. Of the 1.3 million women recruited into the study, ∼65% responded to the second questionnaire, which can be viewed on the study website (http://www.millionwomenstudy.org). All analyses presented here are based on responses to this second questionnaire. All participants have given written informed consent to take part in the study, and ethics approval was provided by Oxford and Anglia Multi-Centre Research and Ethics Committee.

Every study participant is routinely followed-up for death, emigration, and cancer registration, by being flagged on the National Health Service Central Registers using their unique National Health Service number and other personal details. The registers regularly provide study investigators with information on the date of each event in participants, and code the underlying cause of death and cancer site according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD10) (WHO, 1992). For the present analysis, we examined incident renal cell carcinoma (ICD10 C64).

Statistical analyses

Of the 864 381 women who were potentially eligible for these analyses, we excluded women who were registered with any cancer (except non-melanoma skin cancer (ICD10 C44)) before completing the second questionnaire (5.4%), and women who had missing information on alcohol intake or total fluid intake (1.0%). We also excluded a small proportion of women with unfeasibly high fluid intakes (>30 drinks per day; 0.3%) and women who were being treated for diabetes (as both their fluid consumption and cancer rates may be different from that of women without diabetes (3.2%)), leaving 779 369 women included in this analysis.

The questionnaire asked women to record how many non-alcoholic drinks (one drink being defined as one glass or cup) they typically consumed per day, for each of tea, coffee, milk/hot chocolate, water, carbonated/fizzy drinks, and fruit squash. Separate questions asked women to record the number of glasses per week of fruit juice and alcoholic beverages they consumed, which was converted to glasses per day to ensure comparability with the other variables. One alcoholic drink was defined on the questionnaire as one glass of wine, one half-pint of lager or one tot (i.e., a single measure) of spirits. As we had also asked about alcohol consumption at recruitment we used that information for the women who had missing values on the follow-up questionnaire.

Woman-years were calculated from the date of returning the second questionnaire that included questions about intakes of various fluids to the date of any cancer registration (other than non-melanoma skin cancer), death, or the last date of follow-up, whichever came first. The end of follow-up for cancer incidence was 31 December 2007 for East Anglia, South West, and North West (Mersey); 30 June 2007 for Oxford, Thames, West Midlands, and Trent; and 31 December 2006 for Scotland, North West (Manchester/Lancashire), and North Yorkshire. Follow-up was complete for over 99% of the cohort population.

Cox proportional hazards models were applied to estimate relative risks (RRs) of renal cell carcinoma associated with fluid consumption, with attained age as the underlying time variable, using the STATA computing package (STATA Corp., 2007, release 9.2 College Station, TX, USA). Analyses were stratified according to geographical region (10 regions) and socioeconomic status (quintiles of deprivation index, based on postcode of residence) (Townsend et al, 1988), and adjusted for self-reported body mass index (in six categories with cut points at 22.5, 25.0, 27.5, 30.0, and 35.0 kg m–2) and smoking (never, past, current smokers <10, 10–19, ⩾20 cigarettes per day), assigning missing values to a separate category, where necessary. Additional adjustment for use of menopausal hormone therapy and current treatment for high blood pressure changed the risk estimates by <10% and these covariates were not included in the final model. In all analyses, the reference group for total fluid intake was 1–7 drinks per day, and for specific beverages was zero or <1 drink per day. The test for trend across categories of intake was based on the mean intake within each group.

The association of total fluid intake on the risk of renal cell carcinoma was examined in relation to the main known risk factors, including current smoking status (yes, no), body mass index (<25.3, ⩾25.4 kg m–2, divided at the median), and time between completing the second questionnaire and diagnosis (<2, ⩾2 years); evidence of heterogeneity was assessed using χ2-tests.

Results

A total of 779 369 women were followed-up for an average of 5.2 years, during which time 588 incident cases of renal cell carcinoma were identified. The average age at the time the information on fluid consumption was reported was 59 years (5–95th percentile: 53–67 years), and the mean age at renal cell carcinoma diagnosis was 64 years. The relative contribution of specific beverages to overall fluid consumption is shown in Table 1. Overall, tea, water, and coffee contributed the most to total fluid consumption (35, 25, and 21%, respectively) with alcohol, fruit squash, fruit juice, milk, and carbonated drinks each contributing ⩽5% to total fluid intake. Figure 1 shows the distribution of total fluid intake among all women, with a median of 10 drinks per day (5–95th percentile range: 5–16 drinks per day). Water contributed most to the variation in total fluid intake, although women with a high intake of total fluid (i.e., ⩾12 drinks per day) also drank proportionally more alcohol and fruit squash and less tea and coffee than women with a low overall intake (<7 drinks per day). Women who drank ⩾12 drinks each day tended to be younger, have a slightly higher body mass index, were more likely to be current smokers, and less likely to be treated for hypertension than women with a low intake of total fluids (<7 drinks per day; Table 1).

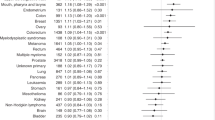

Table 2 shows the risk of renal cell carcinoma associated with consumption of total fluids. Overall, consumption of total fluids was not associated with risk; compared with women who drank <7 drinks per day, the RRs for women who drank 8–9, 10–11, and ⩾12 drinks per day were 1.13 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.89–1.42), 1.06 (95% CI: 0.83–1.35), and 1.15 (95% CI: 0.91–1.45), respectively (P for trend=0.3). Figure 2 shows the association of total fluid intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma by smoking status, body mass index, and time between completing the questionnaire and diagnosis, none of which modified the overall association.

Table 3 shows the risk of renal cell carcinoma associated with consumption of tea, water, and coffee, and Table 4 shows the association with less frequently consumed beverages, including alcohol, fruit squash, fruit juice, milk, and carbonated drinks. There was a significant inverse association with increasing alcohol intake, with an RR of 0.76 (95% CI: 0.61–0.96) for women drinking two or more drinks per day compared with women drinking none or <1 drink per day (P for trend=0.02). Additional adjustment for total fluid intake make little difference to the association with alcohol intake, with an RR of 0.73 (95% CI: 0.58–0.92) for women drinking two or more drinks per day compared with women drinking none or <1 drink per day (P for trend=0.01). There was no association between intake of any individual non-alcoholic beverage and risk of renal cell carcinoma.

Discussion

In this large prospective cohort of middle-aged British women, total fluid intake was not associated with a reduced risk of renal cell carcinoma. For specific beverages, only alcohol consumption was associated with a significant reduction in risk, with no association between intakes of any other beverage on the risk of renal cell carcinoma.

We previously reported that alcohol intake, as measured at recruitment, was associated with a reduced risk of renal cell carcinoma in this study population (Allen et al, 2009); with updated information provided about 3 years after recruitment, the association persists. However, women who drink more alcohol also tend to drink more fluid overall (Table 1), and it has been suggested that this apparent protective effect may be due to a diluting effect of carcinogens related to a high fluid intake rather than to an effect of alcohol per se. Our finding that total fluid intake is not associated with risk of renal cell carcinoma refutes this hypothesis, and is consistent with the results from the two case–control studies (Kreiger et al, 1993; Wolk et al, 1996) and one prospective study (Lee et al, 2006) that have examined this association.

We found little to suggest that consumption of tea or coffee is associated with risk of renal cell carcinoma, which is consistent with the findings from most other studies (Armstrong et al, 1976; Jacobsen et al, 1986; Yu et al, 1986; Asal et al, 1988; McCredie et al, 1988; Maclure and Willett, 1990; Talamini et al, 1990; Benhamou et al, 1993; Kreiger et al, 1993; Wolk et al, 1996; Yuan et al, 1998; Bianchi et al, 2000; Bravi et al, 2007; Hu et al, 2009; Montella et al, 2009). Results from cohort studies are mixed: a pooled analysis of 13 prospective studies reported a small reduction in renal cell carcinoma risk with coffee consumption among women and with tea among men (Lee et al, 2007b); other cohort studies not included in the pooled analysis that have examined coffee intake in relation to renal cell carcinoma have reported inconsistent findings (Stensvold and Jacobsen, 1994; Washio et al, 2005; Nilsson et al, 2010). Taken together, the evidence suggests little or no effect of tea or coffee consumption on renal cell carcinoma risk.

To our knowledge, only three studies have examined water intake in relation to the risk of renal cell carcinoma (Wolk et al, 1996; Lee et al, 2006; Hu et al, 2009), all of which found no association and is consistent with our findings. Few individual studies have examined the association of other beverages on the risk of renal cell carcinoma. One multi-centre case–control study in Canada reported a significant positive association with intake of juice in men but not in women (Hu et al, 2009). Our finding of no association with fruit juice or other beverages including squash, milk, or carbonated drinks on the risk of renal cell carcinoma is consistent with data from a pooled analysis of 13 prospective studies (Lee et al, 2007b).

In this study, women who drank relatively high amounts of total fluid were younger, slightly heavier, and smoked more cigarettes than women who drank lower amounts of total fluid. Nonetheless, all analyses were adjusted for these factors and are therefore unlikely to have influenced the associations found between fluid intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma. Additional adjustment for other lifestyle factors (use of hormone-replacement therapy and current treatment for high blood pressure) made little difference to the risk estimates, suggesting that confounding by these other factors is unlikely. We did not have information on other factors such as family history of renal cell carcinoma or total energy intake, although these factors would have to be related to both fluid intake and renal cell carcinoma risk to have strongly confounded any association.

The strengths of this study include its prospective design and detailed data on specific beverage consumption. The large study size and the relatively wide distribution of intake for most beverages also meant that there was sufficient power to detect an association, if one existed, with the possible exception of milk intake that contained few cases in the highest category of intake. The average intake of tea, coffee, water, squash, fruit juice, milk, and carbonated drinks among this study population is comparable with a national survey of middle-aged British women conducted in 2000–2001 (Office of National Statistics, 2003), and has also been shown to be broadly similar in other respects with that of the general population (Banks et al, 2002). Our measure of total fluid intake does not include the water component of foods. In addition, women will use different glass and cup sizes to represent a measure of one drink, resulting in some misclassification of the volume of fluid consumed. These analyses are also based on the assumption that beverage consumption at the time of completing the questionnaire is a suitable marker of long-term intake. We did ask the same questions 2 years later in a random sample of 1271 women and all beverages, except carbonated drinks, were reported with high consistency (i.e., changed <15%) (Roddam et al, 2005). The average intake of carbonated drinks declined from 0.7 to 0.6 drinks per day and it is difficult to know if this reflects a real change in intake over time or is a consequence of the low overall intake of carbonated drinks. Although it is possible that women with preclinical symptoms of kidney disease may have changed their fluid intake, our finding that the risk estimates were similar between those who were diagnosed <2 years following completion the questionnaire and those diagnosed later, suggests that reverse causation bias did not unduly influence the overall results.

The results from this study suggest that a high fluid intake does not explain the potential protective effect of alcohol on the risk of renal cell carcinoma. It is possible that moderate alcohol consumption may protect against the risk of renal cell carcinoma through its effect on the immune system (Romeo et al, 2007) or on lipid peroxidation (Gago-Dominguez et al, 2002), although perhaps a more likely explanation is via alcohol's reported beneficial effect on insulin sensitivity (Kiechl et al, 1996; Davies et al, 2002), given that obesity and diabetes are risk factors for renal cell carcinoma. More work is needed to examine whether these alternative mechanisms can explain the apparent protective association of moderate alcohol intake on the risk of renal cell carcinoma.

Conclusion

The finding that total fluid consumption and consumption of specific individual beverages was not associated with risk of renal cell carcinoma suggests that any potential protective effect of alcohol on risk of renal cell carcinoma is not a consequence of a high overall fluid intake.

References

Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D, Kan SW, Reeves GK, Brown A, Green J (2009) Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst 101: 296–305

Armstrong B, Garrod A, Doll R (1976) A retrospective study of renal cancer with special reference to coffee and animal protein consumption. Br J Cancer 33: 127–136

Asal NR, Risser DR, Kadamani S, Geyer JR, Lee ET, Cherng N (1988) Risk factors in renal cell carcinoma: I. Methodology, demographics, tobacco, beverage use, and obesity. Cancer Detect Prev 11: 359–377

Banks E, Beral V, Cameron R, Hogg A, Langley N, Barnes I, Bull D, Reeves G, English R, Taylor S, Elliman J, Lole HC (2002) Comparison of various characteristics of women who do and do not attend for breast cancer screening. Breast Cancer Res 4: R1

Benhamou S, Lenfant MH, Ory-Paoletti C, Flamant R (1993) Risk factors for renal-cell carcinoma in a French case-control study. Int J Cancer 55: 32–36

Bianchi GD, Cerhan JR, Parker AS, Putnam SD, See WA, Lynch CF, Cantor KP (2000) Tea consumption and risk of bladder and kidney cancers in a population-based case-control study. Am J Epidemiol 151: 377–383

Bravi F, Bosetti C, Scotti L, Talamini R, Montella M, Ramazzotti V, Negri E, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2007) Food groups and renal cell carcinoma: a case-control study from Italy. Int J Cancer 120: 681–685

Chow WH, Gridley G, Fraumeni Jr JF, Jarvholm B (2000) Obesity, hypertension, and the risk of kidney cancer in men. N Engl J Med 343: 1305–1311

Davies MJ, Baer DJ, Judd JT, Brown ED, Campbell WS, Taylor PR (2002) Effects of moderate alcohol intake on fasting insulin and glucose concentrations and insulin sensitivity in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 287: 2559–2562

Gago-Dominguez M, Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Ross RK, Yu MC (2002) Lipid peroxidation: a novel and unifying concept of the etiology of renal cell carcinoma (United States). Cancer Causes Control 13: 287–293

Hu J, Mao Y, DesMeules M, Csizmadi I, Friedenreich C, Mery L (2009) Total fluid and specific beverage intake and risk of renal cell carcinoma in Canada. Cancer Epidemiol 33: 355–362

IARC (2004) IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol. 83. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France

Jacobsen BK, Bjelke E, Kvale G, Heuch I (1986) Coffee drinking, mortality, and cancer incidence: results from a Norwegian prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst 76: 823–831

Kiechl S, Willeit J, Poewe W, Egger G, Oberhollenzer F, Muggeo M, Bonora E (1996) Insulin sensitivity and regular alcohol consumption: large, prospective, cross sectional population study (Bruneck study). BMJ 313: 1040–1044

Kreiger N, Marrett LD, Dodds L, Hilditch S, Darlington GA (1993) Risk factors for renal cell carcinoma: results of a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 4: 101–110

Lee JE, Giovannucci E, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Curhan GC (2006) Total fluid intake and use of individual beverages and risk of renal cell cancer in two large cohorts. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15: 1204–1211

Lee JE, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Adami HO, Albanes D, Bernstein L, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Cho E, Folsom AR, Freudenheim JL, Giovannucci E, Graham S, Horn-Ross PL, Leitzmann MF, McCullough ML, Miller AB, Parker AS, Rodriguez C, Rohan TE, Schatzkin A, Schouten LJ, Virtanen M, Willett WC, Wolk A, Zhang SM, Smith-Warner SA (2007a) Alcohol intake and renal cell cancer in a pooled analysis of 12 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 801–810

Lee JE, Hunter DJ, Spiegelman D, Adami HO, Bernstein L, van den Brandt PA, Buring JE, Cho E, English D, Folsom AR, Freudenheim JL, Gile GG, Giovannucci E, Horn-Ross PL, Leitzmann M, Marshall JR, Mannisto S, McCullough ML, Miller AB, Parker AS, Pietinen P, Rodriguez C, Rohan TE, Schatzkin A, Schouten LJ, Willett WC, Wolk A, Zhang SM, Smith-Warner SA (2007b) Intakes of coffee, tea, milk, soda and juice and renal cell cancer in a pooled analysis of 13 prospective studies. Int J Cancer 121: 2246–2253

Maclure M, Willett W (1990) A case-control study of diet and risk of renal adenocarcinoma. Epidemiology 1: 430–440

McCredie M, Ford JM, Stewart JH (1988) Risk factors for cancer of the renal parenchyma. Int J Cancer 42: 13–16

Montella M, Tramacere I, Tavani A, Gallus S, Crispo A, Talamini R, Dal Maso L, Ramazzotti V, Galeone C, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2009) Coffee, decaffeinated coffee, tea intake, and risk of renal cell cancer. Nutr Cancer 61: 76–80

Nilsson LM, Johansson I, Lenner P, Lindahl B, Van Guelpen B (2010) Consumption of filtered and boiled coffee and the risk of incident cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 21: 1533–1544

Office of National Statistics (2003) The National Diet & Nutrition Survey: Adults Aged 19 to 64 years: Types and Quantities of Foods Consumed, Vol. 1, HMSO: London

Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull D (2007) Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ 335: 1134

Roddam AW, Spencer E, Banks E, Beral V, Reeves G, Appleby P, Barnes I, Whiteman DC, Key TJ (2005) Reproducibility of a short semi-quantitative food group questionnaire and its performance in estimating nutrient intake compared with a 7-day diet diary in the Million Women Study. Public Health Nutr 8: 201–213

Romeo J, Warnberg J, Nova E, Diaz LE, Gomez-Martinez S, Marcos A (2007) Moderate alcohol consumption and the immune system: a review. Br J Nutr 98 (Suppl 1): S111–S1115

Stensvold I, Jacobsen BK (1994) Coffee and cancer: a prospective study of 43,000 Norwegian men and women. Cancer Causes Control 5: 401–408

Talamini R, Baron AE, Barra S, Bidoli E, La Vecchia C, Negri E, Serraino D, Franceschi S (1990) A case-control study of risk factor for renal cell cancer in northern Italy. Cancer Causes Control 1: 125–131

Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A (1988) Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North. Croon Helm: London

Washio M, Mori M, Sakauchi F, Watanabe Y, Ozasa K, Hayashi K, Miki T, Nakao M, Mikami K, Ito Y, Wakai K, Tamakoshi A (2005) Risk factors for kidney cancer in a Japanese population: findings from the JACC Study. J Epidemiol 15 (Suppl 2): S203–S211

WHO (1992) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision, Vol. 1, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland

Wolk A, Gridley G, Niwa S, Lindblad P, McCredie M, Mellemgaard A, Mandel JS, Wahrendorf J, McLaughlin JK, Adami HO (1996) International renal cell cancer study. VII. Role of diet. Int J Cancer 65: 67–73

Yu MC, Mack TM, Hanisch R, Cicioni C, Henderson BE (1986) Cigarette smoking, obesity, diuretic use, and coffee consumption as risk factors for renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 77: 351–356

Yuan JM, Gago-Dominguez M, Castelao JE, Hankin JH, Ross RK, Yu MC (1998) Cruciferous vegetables in relation to renal cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 77: 211–216

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the women who participated in the Million Women Study. Million Women Study Steering Committee: Joan Austoker, Emily Banks, Valerie Beral, Judith Church, Ruth English, Julietta Patnick, Richard Peto, Gillian Reeves, Martin Vessey, Matthew Wallis. Million Women Study Coordinating Centre staff: Simon Abbott, Krys Baker, Angela Balkwill, Sue Bellenger, Valerie Beral, Judith Black, Anna Brown, Diana Bull, Delphine Casabonne, Barbara Crossley, Dave Ewart, Sarah Ewart, Lee Fletcher, Toral Gathani, Laura Gerrard, Adrian Goodill, Jane Green, Winifred Gray, Joy Hooley, Sau Wan Kan, Carol Keene, Nicky Langston, Bette Liu, Sarit Nehushtan, Lynn Pank, Kirstin Pirie, Gillian Reeves, Andrew Roddam, Emma Sherman, Moya Simmonds, Elizabeth Spencer, Richard Stevens, Helena Strange, Sian Sweetland, Aliki Taylor, Alison Timadjer, Sarah Tipper, Joanna Watson, Stephen Williams. Collaborating UK NHS breast screening centres: Avon, Aylesbury, Barnsley, Basingstoke, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, Cambridge and Huntingdon, Chelmsford and Colchester, Chester, Cornwall, Crewe, Cumbria, Doncaster, Dorset, East Berkshire, East Cheshire, East Devon, East of Scotland, East Suffolk, East Sussex, Gateshead, Gloucestershire, Great Yarmouth, Hereford and Worcester, Kent (Canterbury, Rochester, Maidstone), King's Lynn, Leicestershire, Liverpool, Manchester, Milton Keynes, Newcastle, North Birmingham, North East Scotland, North Lancashire, North Middlesex, North Nottingham, North of Scotland, North Tees, North Yorkshire, Nottingham, Oxford, Portsmouth, Rotherham, Sheffield, Shropshire, Somerset, South Birmingham, South East Scotland, South East Staffordshire, South Derbyshire, South Essex, South Lancashire, South West Scotland, Surrey, Warrington Halton St Helens and Knowsley, Warwickshire Solihull and Coventry, West Berkshire, West Devon, West London, West Suffolk, West Sussex, Wiltshire, Winchester, Wirral, and Wycombe.

Author contributionAll the authors participated in the design and conduct of the study and read and approved the final manuscript. NEA and VB are the guarantors. The Million Women Study is supported by Cancer Research UK, the UK Medical Research Council, and the UK National Health Service breast screening programme. The funders did not influence the conduct of the study, the preparation of this report, or the decision to publish. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, N., Balkwill, A., Beral, V. et al. Fluid intake and incidence of renal cell carcinoma in UK women. Br J Cancer 104, 1487–1492 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.90

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2011.90

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association of soft drinks and 100% fruit juice consumption with risk of cancer: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (2023)

-

Coffee consumption and risk of renal cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort evidence

Cancer Causes & Control (2022)

-

Coffee and cancer risk: A meta-analysis of prospective observational studies

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Long-term dietary sodium, potassium and fluid intake; exploring potential novel risk factors for renal cell cancer in the Netherlands Cohort Study on diet and cancer

British Journal of Cancer (2014)

-

Alcohol intake and renal cell cancer risk: a meta-analysis

British Journal of Cancer (2012)