Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a non-standard, intermittent imatinib treatment in elderly patients with Philadelphia-positive chronic myeloid leukaemia and to answer the question on which dose should be used once a stable optimal response has been achieved. Seventy-six patients aged ⩾65 years in optimal and stable response with ⩾2 years of standard imatinib treatment were enrolled in a study testing a regimen of intermittent imatinib (INTERIM; 1-month on and 1-month off). With a minimum follow-up of 6 years, 16/76 patients (21%) have lost complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) and major molecular response (MMR), and 16 patients (21%) have lost MMR only. All these patients were given imatinib again, the same dose, on the standard schedule and achieved again CCyR and MMR or an even deeper molecular response. The probability of remaining on INTERIM at 6 years was 48% (95% confidence interval 35–59%). Nine patients died in remission. No progressions were recorded. Side effects of continuous treatment were reduced by 50%. In optimal and stable responders, a policy of intermittent imatinib treatment is feasible, is successful in about 50% of patients and is safe, as all the patients who relapsed could be brought back to optimal response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 80% of patients with Philadelphia-positive (Ph+), BCR-ABL1+, chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) are alive after >5 years and are projected to have a life expectancy very close or even identical to that of a non-leukaemic matched control population.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 These results were obtained using the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib (Gleevec or Glivec, Novartis Pharmaceutics), frontline.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Some of these patients, in a proportion estimated to range between 20% and 40%, achieve a deep molecular response (DMR), that is to say a BCR-ABL1 transcripts level ⩽0.01% on the International Scale.9, 10, 11, 12 About 50% of them were reported to maintain that remission status after discontinuation of imatinib and to achieve a stable treatment-free remission (TFR).13, 14, 15, 16 The introduction of the so-called second-generation TKIs, both in first and second line, is expected to fare even better, with up to 50% or more of the patients achieving a DMR,17, 18, 19, 20 and up to ⩾50% of them entering into a TFR status. If these expectations will be fulfilled, the proportion of patients who will be in TFR will range between 25% and 50%. However, about ⩾50% of all patients will not be able to discontinue, and for them, the current policy is to continue the treatment with the same TKI, at the same dose and schedule, indefinitely and lifelong.3, 5 Until today, the case of the chronic treatment of these patients has not received the same attention as the case of TFR policies. But the issue is important for obvious reasons of quality of life,21 treatment-related side effects and complications22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and also because of drug and management costs.3, 5, 30

For these reasons, we designed and initiated a pilot study testing the effect of a non-standard, dose-reduced, policy of imatinib treatment.31 We report here on the long-term results of that trial.

Patients and methods

The study (EUDRACT protocol number 2007-005102-42, approved by the Ethic Committee of the Spedali Civili of Brescia, Italy and registered at ClinicalTrials.Gov with the number: NCT00858806) was limited to patients aged ⩾65 years who had been treated first line with imatinib once daily (OD) for chronic phase CML, for a minimum of 2 years, and were in complete cytogenetic response (CCyR). One hundred and fourteen patients were screened in 24 GIMEMA (Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto) centres. Nineteen patients (17%) did not fit the inclusion criteria, 19 (17%) did not consent and 76 were enrolled. The median age at enrolment was 72 years (range 65–83 years). The median duration of imatinib treatment was 5.75 years (range 2.0–6.6 years). Sokal risk32 distribution at diagnosis was 33% low risk, 55% intermediate risk and 12% high risk. At enrolment, all patients were in CCyR, and all but one were in major molecular response (MMR or MR3.0, BCR-ABL1 transcripts level ⩽0.1% on the International Scale).

The daily dose of imatinib was not modified (400 mg OD in 81% of patients, 200–300 mg OD in 17% of patients and 600 mg in one patient), but imatinib was given 1 week on/1 week off for 1 month, 2 weeks on/2 weeks off for another 2 months and then on a 1 month on/1 month off schedule. The protocol originally mandated to proceed with the intermittent schedule as long as the CCyR was maintained so that the return to continuous daily treatment was mandatory only in case of CCyR loss. After 2 years, an amendment allowed a return to the continuous daily schedule also in case of MMR loss.

The cytogenetic response was assessed by chromosome banding analysis of marrow cell metaphases or by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of peripheral blood cell nuclei, as described elsewhere.33 The cytogenetic test was performed every 6 months for the first 2 years, and then only in case of loss of MR3.0. A CCyR was defined either by the absence of Ph+ metaphases out of at least 20 metaphases or by <1% BCR-ABL1+ nuclei out of >200 nuclei. The molecular response was evaluated every 3 months and was reported according to the International Scale by reverse transcriptase-PCR of peripheral blood leukocytes.34, 35, 36 The tests were performed at one GIMEMA reference laboratory for 4 years, then also at other laboratories that had received their conversion factor through the EUTOS project36 and were certified by the Labnet GIMEMA network. A mutational analysis, by Sanger sequencing technique,37 was performed in the Bologna reference laboratory in all cases of loss of CCyR or MR3.0. The definition of the phases of the disease and of response was those recommended by EuropeanLeukemiaNet 2013.3

Statistics

The Kaplan–Meier method38 was used to estimate overall survival. Death by any cause was the event of interest for overall survival. CCgR loss (CBA-positivity), MMR (MR3.0) loss and the probability of continuing INTERIM were calculated using the cumulative incidence procedure.39 Death was considered competing risk for CCgR and MMR loss, whereas death and refusal were the competing risks for the probability of continuing INTERIM.

Results

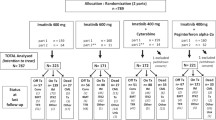

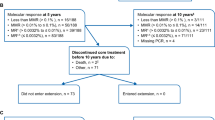

The results of intermittent imatinib treatment, with a median follow-up of 5.75 years (range 2.0–6.6 years) are shown in the flow diagram (Figure 1). Sixteen patients (21%) lost CCyR and MR3.0, 11 of them during the first 2 years and 5 later on. One of these patients was lost to follow-up. All the remaining 15 patients recovered a CCyR, with MR3.0 in 13 patients and MR4.0 in one. Sixteen patients (21%) lost MR3.0 after the second year. All these patients recovered an MR3.0, and two of them achieved a DMR (MR4.0 in one case and MR4.5 in one case). One patient went off the study because of an atrial fibrillation. He was back on standard imatinib, then was switched to nilotinib and is in MMR. Four patients withdrew their consent after 24–70 months. They went back to standard daily imatinib; 3 are in MR3.0, the fourth achieved a MR4.0 and is currently in TFR. Nine patients (12%) died after 24–60 months, being in MR3.0, of the causes that are listed in the flow diagram, namely another cancer (five patients), chronic pulmonary obstructive disease (two patients) and cardiovascular events (two patients). The median age at death was 75 years (range 72–80). No patients progressed to accelerated phase or blastic phase. No BCR-ABL1 kinase domain point mutations were detected at the time of CCyR or MR3.0 loss.

The distribution over time of the loss of CCyR and of MR3.0 is shown in Figures 2a and b, respectively. The probability of maintaining the intermittent treatment schedule is shown in Figure 3a, where events were the return to the continuous, daily treatment, whatever the reason for that. At 6 years, 48% of patients were still on the intermittent schedule. Overall survival is shown in Figure 3b, where it should be noticed that all deaths occurred in remission. There were no progressions.

(a) Probability of maintaining the CCyR. In all, 16/76 patients (21%) lost CCyR, of whom 11 during the first 2 years and 5 later on. The probability of remaining in CCyR was 84% (95% CI 73–90) at 2 years, 81% (95% CI 69–88) at 4 years and 76% (95% CI 64–84) at 6 years. All 16 patients but 1 who was lost to follow-up were back to continuous imatinib treatment, same daily dose, and recovered the CCyR. (b) Probability of maintaining the MMR. In all, 32/76 patients (42%) lost MMR, including the 16 patients who had lost also the CCyR (Figure 1). The probability of remaining in MMR was 67% (95% CI 54–76) at 2 years and 60% (95% CI 47–70) at 4 and 6 years. All 32 patients but 1 who was lost to follow-up were back to continuous imatinib treatment, same daily dose, and recovered the MMR.

(a) Probability of remaining in the intermittent imatinib schedule (INTERIM). In all, 46/76 patients (61%) discontinued the intermittent schedule, of whom 24 during the first 2 years and 22 later on. The probability of maintaining the intermittent treatment schedule was 74% (95% CI 62–82) at 2 years, 59% (95% CI 46–69) at 4 years and 48% (95% CI 35–59) at 6 years. (b) Overall survival. No patients progressed and died of leukaemia. Nine patients (median age at death, 75 years) died in MMR for an overall survival of 87% (95% CI 78–95%) at 6 years.

With a median follow-up of about 6 years, 30 patients are still on intermittent treatment taking the same imatinib dose as at baseline, 1 month on/1 month off. Four of them are in CCyR, 4 are in MR3.0, 20 are in MR4.0 and 2 are in MR4.5.

Discussion

The current policies of TKI treatment of chronic phase CML mandate using TKIs at their respective approved or maximum tolerated doses lifelong, with the possibility of opening a window for treatment discontinuation when a DMR has been achieved and maintained for an as yet unspecified period of time.3, 5, 12, 16, 40 The window for treatment discontinuation can be enlarged in some of the patients who received imatinib first line, by switching early or late to a second-generation TKI,40, 41, 42, 43 as well as using second-generation TKIs first line.17, 18, 19, 20, 44, 45 Other policies have not been tested prospectively, particularly for treatments alternative to discontinuation, when discontinuation is not possible. The importance of the compliance to the treatment dose is highlighted by studies reporting that poor compliance is associated with a poorer molecular response.46, 47 However, it is time to open a debate not on compliance but on which dose should be used for chronic treatment, once a stable, optimal response has been achieved.

The concept of dose adaptation for chronic treatment can be tested in many different ways. Different schedules, such as a continuous daily treatment with a reduced dose or 1 day on/1 day off or 1 week on/1 week off, could be tested. In this exploratory study, it was decided to maintain the standard daily dose on a 1 month on/1 month off schedule. No pharmacokinetic studies were performed, but it is conceivable that the plasma concentration of imatinib fell to zero during the month off.

This study shows that a policy of imatinib reduction to 50% of the initial standard dose was associated with a substantial loss of response in 42% of patients but had no negative effects on outcome, particularly on progression and leukaemia-related deaths. It should be noted that at baseline all patients were in MMR, while after 6 years of intermittent treatment 22 of the original 76 patients (29%) were in DMR and could be eligible for a trial of treatment discontinuation. Therefore, even an intermittent schedule can improve the response, with time. A systematic, prospective study of the quality of life was not designed and performed. All these patients were tolerating imatinib well. Only 20 of them were complaining of minor side effects. In all, 50% of them reported the disappearance of the side effects, particularly of muscle pain and cramps, and of fluid retention. No evidence of a ‘discontinuation syndrome’ was found, as it was reported in patients discontinuing imatinib in the EUROSKI study.48, 49 In this exploratory study, only elderly patients (⩾65 years) were selected and enrolled, because elderly patients tolerate TKIs less well, have more comorbidities, take more medications and have a shorter life expectancy. Moreover, the median age at diagnosis is already close to 60 years,50 and the proportion of elderly patients is destined to grow with time. However, also the younger patients who will not achieve a TFR will deserve attention. Although there is only another study (DESTINY study—ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01804985) looking for the minimum effective dose of any TKI, there is no doubt that the so called standard or approved dose is critical for achieving an optimal response as fast as possible and to prevent progression to blastic phase.3, 5 However, the issue is not to challenge the choice of the initial dose but to understand if the same dose is required indefinitely, and if so, for which purpose. This challenge has biological, clinical and financial implications. Biologically, almost all studies suggest that once an optimal response is achieved, the residual Ph+ cells may not be completely BCR-ABL1 addicted, and are resistant to TKI inhibition,51, 52 so that it may be necessary to consider other approaches testing other drugs in trials where toxicity and safety may prevail.53 In any case, those residual Ph+ cells can hardly give rise to new resistant Ph+ clones, because late relapses are exceptional.9 Therefore, the probability of dying of leukaemia becomes so small that one must worry more of other diseases and of the risk of treatment-related complications, a risk that will never be equal to zero, and that is difficult to predict over a very long period of time.3, 5, 22, 23, 24 From a financial perspective, the indefinite continuation of the standard, approved dose will expand the cost of the treatment exponentially.30 These considerations are also a valid argument in favour of a policy of treatment discontinuation and TFR, a policy that is more radical and more appealing.11, 12, 16 However, the point is not only which policy is ‘better’. The point is to acknowledge that a policy of TFR cannot be always successful, because at least 50% of patients are estimated to never reach a TFR, even with the largest use of second-generation TKIs. For the patients who do not achieve a TFR, it is necessary to reconsider some current concepts of treatment and to begin to look for a ‘minimum effective therapy’.

On these bases, we continue to work on the intermittent schedule with a standard daily dose, and we are now testing a progressive increase of the off-treatment period, up to 1 month on/3 months off.

References

Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Baccarani M . Chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 2005; 370: 342–350.

Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Jabbour E, Garcia-Manero G, Quintas-Cardama A, Shan J et al. Improved survival in chronic myeloid leukemia since the introduction of imatinib therapy: a single-institution historical experience. Blood 2012; 119: 1981–1987.

Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, Hochhaus A, Soverini S, Apperley JF et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood 2013; 122: 872–884.

Hoglund M, Sandin F, Hellstrom K, Björeman M, Björkholm M, Brune M et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor usage, treatment outcome, and prognostic scores in CML: report from the population-based swedish CML registry. Blood 2013; 122: 1284–1292.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, version 1, 2015. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cml.pdf.

Hochhaus A, O’Brien S, Guilhot F, Druker BJ, Branford S, Foroni L et al. Six-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2009; 23: 1054–1061.

Gambacorti-Passerini C, Antolini L, Mahon FX, Guilhot F, Deininger M, Fava C et al. Multicenter independent assessment of outcome in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011; 103: 553–561.

Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Jung-Munkwitz S, Leitner A, Muller MC, Pletsch N et al. Tolerability-adapted imatinib 800 mg/d versus 400 mg/d versus 400 mg/d plus interferon-alpha in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1634–1642.

Hehlmann R, Muller MC, Lauseker M, Hanfstein B, Fabarius A, Schreiber A et al. Deep molecular response is reached by the majority of patients treated with imatinib, predicts survival, and is achieved more quickly by optimized high-dose imatinib: results from the randomized CML-Study 4. J Clin Oncol 2013; 32: 415–423.

Etienne G, Dulucq S, Nicolini FE, Morisset F, Fort MP, Schmitt A et al. Achieving deeper molecular response is associated with a better clinical outcome in chronic myeloid leukemia patients on imatinib front-line therapy. Haematol 2014; 99: 458–464.

Mahon FX, Etienne G . Deep molecular response in chronic myeloid leukemia: the new goal of therapy? Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 310–322.

Apperley J . Chronic myeloid leukemia. Semin Hematol 2014; 5: 1–13.

Mahon FX, Réa D, Guilhot J, Guilhot F, Huguet F, Nicolini F et al. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic mye loid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 1029–1035.

Ross DM, Branford S, Seymour JF, Schwarer AP, Arthur C, Yeung DT et al. Safety and efficacy of imatinib cessation for CML patients with stable undetectable minimal residual disease: results from the TWISTER study. Blood 2013; 122: 515–522.

Thielen N, van der Holt B, Cornelissen JJ, Verhof GE, Gussinklo T, Biedmond BJ et al. Imatinib discontinuation in chronic phase myeloid leukaemia patients in sustained complete molecular response: a randomised trial of the Dutch-Belgian Cooperative Trial for Haemato-Oncology (HOVON). Eur J Cancer 2013; 49: 3242–3246.

Mahon FX . Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase therapy in CML. Ann Hematol 2015; 94: 187–193.

Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, le Coutre P, Etienne G, Lobo C et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. New Engl J Med 2010; 362: 2251–2259.

Kantarjian HM, Shah NP, Cortes JE, Baccarani M, Agarwal MB, Undurraga MS et al. Dasatinib or imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: 2-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION). Blood 2012; 119: 1123–1129.

Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Saglio G, Steegmann JL, Shah NP, Boquè C et al. Early response with dasatinib or imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: 3-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION). Blood 2014; 123: 494–500.

Larson R, Kim D, Issaragrisil S, le Coutre P, Llacer Dorlhiac PE, Etienne G et al. Efficacy and safety of Nilotinib (NIL) vs Imatinib (IM) in patients (pts) with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP): long-term follow-up (f/u) of ENESTnd. Blood 2014; 124: 4541.

Efficace F, Baccarani M, Breccia M, Alimena G, Rosti G, Cottone F et al. Health-related quality of life in chronic myeloid leukemia patients receiving long-term therapy with imatinib compared with the general population. Blood 2011; 118: 4554–4560.

Valent P . Severe adverse events associated with the use of second-line BCR/ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors: preferential occurrence in patients with comorbidities. Haematol 2011; 96: 1395–1397.

Steegmann JL, Cervantes F, le Coutre P, Porkka K, Saglio G . Off-target effects of BCR-ABL1 inibitors and their potential long-term implications in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2012; 53: 2351–2361.

Breccia M, Tiribelli M, Alimena G . Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for elderly chronic myeloid leukemia: a systematic review of efficacy and safety data. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2012; 84: 93–100.

Giles FJ, Mauro MJ, Hong F, Ortmann CE, McNeill C, Woodman RC et al. Rates of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase treated with imatinib, nilotinib, or non-tyrosine kinase therapy: a retrospective cohort analysis. Leukemia 2013; 27: 1310–1315.

Kim TD, Rea D, Schwarz M, Grille P, Nicolini FE, Rosti G et al. Peripheral artery occlusive disease in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with nilotinibor imatinib. Leukemia 2013; 27: 1316–1321.

Irvine E, Williams C . Treatment-, patient-, and disease-related factors and the emergence of adverse events with tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Pharmacotherapy 2013; 33: 868–881.

Valent P, Hadzijusufovic E, Schernthaner GH, Wolf D, Rea D, le Coutre Pl . Vascular safety issues in CML patients treated with BCR/ABL1 kinase inhibitors. Blood 2015; 125: 901–906.

Cortes J, Mauro M, Steegmann JL, Saglio G, Malhotra R, Ukropec JA et al. Cardiovascular and pulmonary adverse events in patients treated with BCR-ABL inhibitors: data from the FDA adverse event reporting system. Am J Hematol 2015; 90: E66–E72.

Experts in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. The price of drugs for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a reflection of the unsustainable prices of cancer drugs: from the perspective of a large group of CML experts. Blood 2013; 121: 4439–4442.

Russo D, Martinelli G, Malagola M, Skert C, Soverini S, Iacobucci I et al. Effects and outcome of a policy of intermittent imatinib treatment in elderly patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2013; 121: 5138–5144.

Sokal JE, Cox EB, Baccarani M, Tura S, Gomez GA, Robertson GE et al. Prognostic discrimination in "good-risk" chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood 1984; 63: 789–799.

Testoni N, Marzocchi G, Luatti S, Amabile M, Baldazzi S, Stacchini M et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia: a prospective comparison of interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization and chromosome banding analysis for the definition of complete cytogenetic response: a study of the GIMEMA CML WP. Blood 2009; 114: 4939–4943.

Hughes T, Deininger M, Hochhaus A, Brandford S, Radich J, Kaeda J et al. Monitoring CML patients responding to treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors:review and recommendations for harmonizing current methodology for detecting BCR—ABL transcripts and kinase domain mutations and for expressing results. Blood 2006; 108: 28–37.

Cross NC, White HE, Muller MC, Saglio G, Hochhaus A . Standardized definitions of molecular response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2012; 26: 2172–2175.

Cross NC, Hochhaus A, Müller MC . Molecular monitoring of chronic myeloid leukemia: principles and interlaboratory standardization. Ann Hematol 2015; 94: 219–225.

Soverini S, Hochhaus A, Nicolini FE, Gruber F, Lange T, Saglio G et al. BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2011; 118: 1208–1215.

Kaplan PM, Meier HT . Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958; 53: 457–481.

Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer B . Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risk: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med 1999; 18: 695–706.

Ross DM, Hughes TP . How I determine if and when to recommend stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment for chronic myeloid leukaemia. B J Haematol 2014; 166: 3–11.

Quintás-Cardama A, Jabbour EJ . Considerations for early switch to nilotinib or dasatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia with inadequate response to first-line imatinib. Leuk Res 2013; 37: 487–495.

Hughes T, White D . Which TKI? An embarrassment of riches for chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2013; 2013: 168–175, Presented at the 55th American Society of Hematology Meeting; 7–10 December; New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Yeung DT, Osborn MP, White DL, Brandford S, Braley J, Herschtal A et al. TIDEL-II: first-line use of imatinib in CML with early switch to nilotinib for failure to achieve time-dependent molecular targets. Blood 2015; 125: 915–923.

Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Shan J, Quintas-Cardama A, Garcia-Manero G et al. Front-line therapy with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with early chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: what is the optimal response? J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4260–4265.

Shami PJ, Deininger M . Evolving treatment strategies for patients newly diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukemia: the role of second-generation BCR-ABL inhibitors as first-line therapy. Leukemia 2012; 26: 214–224.

Noens L, van Lierde MA, De Bock R, Verhoef G, Zachèe P, Berneman Z et al. Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the ADAGIO study. Blood 2009; 113: 5401–5411.

Marin D, Bazeos A, Mahon FX, Eliasson L, Milojkovic D, Bua M et al. Adherence is the critical factor for achieving molecular responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who achieve complete cytogenetic response on imatinib. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 2381–2388.

Mahon FX, Richter J, Guilhot J, Muller MC, Dietz C, Porkka K et al. Interim analysis of a Pan European Stop Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Trial in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: the EURO-SKI study. Blood 2014, 124 (Abs 151).

Richter J, Söderlund S, Lübking A, Dreimane A, Lotfi K, Markevarn B et al. Musculoskeletal pain in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia after discontinuation of imatinib: a tyrosine kinase inhibitor withdrawal syndrome? J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 2821–2823.

Hoffmann V, Baccarani M, Hasford J, Lindoerfer D, Burgstaller S, Sertic D et al. The EUTOS population-based registry incidence and clinical characteristics of 2094 CML patients in 20 European countries. Leukemia 2015; 29: 1336–1343.

Chomel JC, Bonnet ML, Sorel N, Bertrand A, Meunier MC, Fichelson S et al. Leukemia stem cell persistence in chronic myeloid leukemia patients with sustained undetectable molecular residual disease. Blood 2011; 118: 3657–3660.

Chu S, McDonald T, Lin A, Chakraborty S, Huang Q, Snyder DS et al. Persistence of leukemia stem cells in chronic myelogenous leukemia patients in prolonged remission with imatinib treatment. Blood 2011; 118: 5565–5572.

Ahmed W, Van Etten RA . Alternative approaches to eradicating the malignant clone in chronic myeloid leukemia: tyrosine-kinase inhibitor combinations and beyond. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2013; 2013: 189–200, Presented at the 55th American Society of Hematology Meeting; 7–10 December, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by EuropeanLeukemiaNet (ELN)–European Treatment and Outcome Study (EUTOS) and by Cofin 2009. Special thanks to the following authors for their participation in the development of the manuscript: Francesco Fabbiano (Palermo), Umberto Vitolo (Torino), Marco Gobbi and Ivana Pierri (Genova), Roberto Cairoli (Milano), Francesco Di Raimondo (Catania), Giuliana Alimena (Roma La Sapienza), Alessandro Rambaldi (Bergamo), Giuseppe Saglio (Orbassano), Giuseppe Visani (Pesaro), Paolo De Fabritiis (Roma Tor Vergata), Renato Fanin (Udine), Piero Galieni (Ascoli Piceno), Emanuele Angelucci (Cagliari), Caterina Musolino (Messina), Giorgina Specchia (Bari), Gianluca Gaidano (Novara), Francesco Rodeghiero (Vicenza), Alberto Bosi (Firenze), Angela Malpignano (Brindisi), and Giuseppe Fioritoni (Pescara). Special thanks to Multilingue Group for English revision (http://www.multilingue.it).

Author contributions

Domenico Russo and Michele Baccarani designed the study; all the authors collected the data; Domenico Russo, Michele Baccarani, Giannatonio Rosti, Michele Malagola, Crisitna Skert, Antonio De Vivo and Bruno Mario Cesana analysed the data; all the authors wrote the manuscript and gave final approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Domenico Russo, Patrizia Pregno and Simona Soverini receives compensation as a consultant for Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ariad. Elisabetta Abruzzese receives compensation as a consultant for Ariad, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Takeda and Pfizer. Giovanni Martinelli receives compensation as a consultant for Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Gianantonio Rosti, Fausto Castagnetti and Michele Baccarani receives compensation as a consultant for Novartis, Ariad, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Mario Tiribelli receives compensation as a consultant for Novartis, BMS and Ariad. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Russo, D., Malagola, M., Skert, C. et al. Managing chronic myeloid leukaemia in the elderly with intermittent imatinib treatment. Blood Cancer Journal 5, e347 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2015.75

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2015.75

This article is cited by

-

A systematic review of non-standard dosing of oral anticancer therapies

BMC Cancer (2018)

-

Gute Chancen mit intermittierend Imatinib

Info Onkologie (2015)