Abstract

Aim:

To study the molecular mechanisms underlying α-tocopheryl succinate (α-TOS)-induced apoptosis in erbB2-positive breast cancer cells and to determine whether α-TOS and the human recombinant TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (hrTRAIL) act synergically to induce cell death of erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells.

Methods:

The annexin V binding method was used to measure apoptosis induced by α-TOS and/or hrTRAIL. RT-PCR and Western blotting were performed to detect gene and protein expression. A colorimetric assay was performed to detect caspase activity. The TransAMTM NF-κB p65 kit was used to assess NF-κB activation.

Results:

α-TOS (100 μmol/L) significantly inhibited NF-κB nuclear translocation in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells; this inhibition is expected to result in the inactivation of NF-κB. α-TOS (50 and 100 μmol/L) inhibited the expression of Flice-like inhibitory protein (FLIP) and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (c-IAP1) in erbB2-positive cells. α-TOS (100 μmol/L) inhibited Akt activation and augmented the activity of caspase 3 and caspase 8 in breast cancer cells expressing erbB2. α-TOS (50 μmol/L) and hrTRAIL (30 mg/mL) acted synergically to induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells. α-TOS also decreased the hrTRAIL-induced transient activation of NF-κB .

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that α-TOS mediates the apoptosis of erbB2-positive breast cancer cells and acts synergically with hrTRAIL via the NF-κB pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer cells that express erbB2 are resistant to many drugs1, 2. The major complication associated with erbB2 expression is linked to auto-activation of downstream signaling pathway(s), such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which leads to the activation of Akt3, a serine/threonine kinase that promotes cellular survival4. Akt causes activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)5, 6. In most non-transformed cells, NF-κB complexes (heterotrimers usually composed of the p50 and p65 subunits bound to an inhibitor subunit, IκB) are largely cytoplasmic. Activation of NF-κB causes it to translocate into the nucleus and bind to the promoter regions of specific pro-survival genes, such as those coding for IAPs7 and the caspase 8 inhibitor, FLIP8. Therefore, agents that inhibit NF-κB activation in erbB2-expressing cancer cells are of clinical interest.

Vitamin E (VE) analogs, a novel class of VE compounds with strong pro-apoptotic activity epitomized by α-TOS, have been shown to trigger apoptosis in a variety of cancer cells9. Recently, we found that α-TOS induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells expressing erbB210. Using pre-clinical models, it has been shown that hrTRAIL is a potent anticancer agent11. However, some tumor cells possess intrinsic resistance to hrTRAIL12, one of the reasons for this is that hrTRAIL can induce transient NF-κB activation in some cell types13. A cooperative apoptotic effect of α-TOS and hrTRAIL has been observed in human malignant mesothelioma cells11.

To determine the molecular mechanisms by which α-TOS induces apoptosis in erbB2-positive breast cancer cells and synergizes with hrTRAIL, we measured the activation of Akt and NF-κB, the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65, the caspase activity and the expression of caspase inhibitors. We found that the NF-κB pathway plays a critical role in α-TOS-induced breast cancer cell apoptosis and its synergy with hrTRAIL.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Human breast cancer cell lines MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 were routinely cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. At approximately 50% to 70% confluence, cells were treated with up to 100 μmol/L α-TOS (Sigma Chemical Co, Missouri, USA) and/or up to 30 ng/mL hrTRAIL (Sigma Chemical Co, Missouri, USA)14. After exposure to the drugs for the required period of time, cells were harvested and assessed by different methods (see below).

Western blotting

Whole cell lysates were obtained using a kit (Beijing SBS Genetech Co, Ltd, Beijing, China). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were obtained using the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (KeyGEN, Nanjing, China). Protein samples were denatured, resolved in 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies (Santa Cruz, California, USA) then incubated further with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary IgG. Anti-β-actin or anti-histone 1 (Santa Cruz, California, USA) was used as a control for protein loading.

Assessment of markers of apoptosis

Apoptosis was quantified by flow cytometry using the Annexin V method as described elsewhere10. Cells were plated at a seeding density of 105 cells/well in 24-well plates. After overnight incubation, cells were treated with α-TOS and/or hrTRAIL for varying durations. Both floating and attached cells were harvested, washed with PBS, resuspended in 0.2 mL binding buffer (10 mmol/L HEPES, 140 mmol/L NaCl, and 5 mmol/L CaCl2, pH 7.4), incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with 2 μL annexin V-FITC, supplemented with 200 μL propidium iodide (PI) (50 μg/mL), and analyzed by flow cytometry using channel 1 for annexin V-FITC binding and channel 2 for PI staining. Cell death was consistently quantified as the percentage of cells with high annexin V binding plus PI staining.

RNA interference (RNAi)

Validated, erbB2-specific short interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides and nonspecific scrambled siRNA were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX, USA). Briefly, cells were allowed to reach 50% confluence, supplemented with 60 pmol/L siRNA pre-incubated with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and overlaid with OptiMEM. Cells were washed 24 h later with PBS, overlaid with complete DMEM, and cultured for an additional 24 h. Knockdown efficiency was confirmed by Western blot before using the cells for further experiments15.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reverse transcription was carried out using AMV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and oligo(dT)18 primer. One to three microliters of the cDNA was used for amplification, and PCR was run for 30 cycles. The specific oligonucleotide primer pairs for certain genes and the expected sizes of the PCR products are as follows: c-IAP1 FW, 5′-GAA TAC TCC CTG TGA TTA ATG GTG CCG TGG-3′ and RV, 5′-TCT CTT GCT TGT AAA GAC GTC TGT GTC TTC-3′, 230 bp; FLIP FW, 5′-CAT ACT GAG ATG CAA GAA TT-3′ and RV, 5′-GCT GAA GTC ATC CAT GAG GT-3′, 875 bp; β-actin FW, 5′-TGA CGG GGT CAC CCA CAC TGT GCC-3′ and RV, 5′-CTA GAA GCA TTT GCG GTG GAC GAT GGA GGG-3′, 662 bp. The conditions used for PCR amplification were as follows: 94 °C for 30 s, 65 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, 30 cycles in a 25-μL reaction.

Assessment of NF-κB activation

Activation of NF-κB was estimated using the TransAMTM NF-κB p65 Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 5×106 cells treated with α-TOS and/or hrTRAIL or TNF were washed with PBS and spun down. The cells were lysed with NP40 in hypotonic buffer and then centrifuged to separate the nuclei. Nuclear proteins were extracted with complete lysis buffer, transferred into wells containing the immobilized NF-κB (p65) consensus sequence and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The wells were washed, and the bound p65 protein was detected by HRP-dependent staining following incubation with anti-p65 IgG and HRP-conjugated secondary IgG. The absorbance at 450 nm, which was assessed by microplate reader, reflected the amount of bound p6516.

Caspase 3 and caspase 8 activity assays

The activities of caspase 3 and caspase 8 were measured by cleavage of the chromogenic caspase substrates, Ac-DEVD-pNA (acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp p-nitroanilide) and Ac-IETD-pNA (acetyl-Ile-Glu-Thr-Asp p-nitroanilide), respectively17. Approximately 30 μg of total protein was added to reaction buffer containing Ac-DEVD-pNA (2 mmol/L) or Ac-IETD-pNA (2 mmol/L) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The absorbance of yellow pNA cleaved from its corresponding precursor was measured using a spectrometer at 405 nm. The specific caspase activity was normalized by total protein of the cell lysates and expressed as the fold increase of the baseline caspase activity in control cells cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were placed on sterile coverslips in 12-well plates overnight and then fixed with 100% methanol for 3 min, 1% H2O2-methanol for 5 min, 95% methanol for 3 min and 50% methanol for 3 min. The cells were then exposed to anti-p65 IgG (Santa Cruz, California, CA, USA), followed by a biotinylated secondary antibody. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with streptavidin-HRP. Finally, protein expression was detected using DAB solution and observed by microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Data were obtained from at least three different experiments, and the results are presented as the mean±SD. Significance between data points was assessed using the Student's t-test, and the data were considered significantly different when P<0.05.

Results

α-TOS inhibited NF-κB nuclear translocation in breast cancer cells expressing erbB2

We determined that both MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cell lines express erbB2 and phosphorylated Akt (pAkt) and similar levels of Akt (Figure 1A). This result is consistent with previous data showing that the expression of erbB2 leads to activated Akt. Akt activation leads to the activation of NF-κB, which controls the expression of a variety of antiapoptotic genes. Immunocytochemistry for the p65 protein (a subunit of NF-κB) showed much weaker nuclear staining in MDA-MB-453 (Figure 1B) and MCF7 (data not shown) cells after treatment with 100 μmol/L α-TOS than in untreated cells. Western blotting showed that p65 protein decreased in the nuclear fraction and increased in the cytoplasmic fraction after treatment with α-TOS in both cell lines (Figure 1C). We can conclude that α-TOS inhibited the translocation of p65 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in breast cancer cells expressing erbB2.

α-TOS inhibited p65 nuclear translocation in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells. (A) MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells were lysed and the whole cell lysate was probed by immunoblotting for the levels of erbB2, Akt and p-Akt. (B) MDA-MB-453 cells were treated with α-TOS for 24 h. Cells were then fixed for p65 immunostaining. (C) Both cell lines were treated with α-TOS as indicated. As shown, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions (60 μg protein per sample) were resolved on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and probed by immunoblotting for the expression of p65. The images are representative of three independent experiments.

α-TOS inhibited Akt activation

Because the activation of Akt correlates with its phosphorylation at the Thr308 and Ser473 residues, we examined the amount of Akt and pAkt (Ser473) after treatment with α-TOS. Figure 2 shows that α-TOS treatment decreased the level of pAkt in MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 cells. The level of total Akt was not altered in either cell line after treatment with α-TOS.

α-TOS suppressed c-IAP1 and FLIP expression in erbB2-positive breast cancer cells

NF-κB controls the expression of pro-survival genes such as members of the IAP family7 and the caspase 8 inhibitor, FLIP8. This characteristic prompted us to investigate the effects of α-TOS on IAP and FLIP expression. We detected the expression of c-IAP1, c-IAP2 (both members of IAP family) and FLIP after treatment with α-TOS. We determined that α-TOS suppressed c-IAP1 and FLIP expression (Figure 3) but had no effect on c-IAP2 expression (data not shown). Figure 3A shows that α-TOS reduced the amount of c-IAP1 mRNA in MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Figure 3B shows that α-TOS reduced c-IAP1 protein expression in both cell lines. A decrease in the amount of FLIP mRNA was also found in α-TOS-treated MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells (Figure 3C). Figure 3D shows that α-TOS reduced FLIP protein expression in both cell lines.

α-TOS inhibited c-IAP1 and FLIP expression in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells. MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells (as shown) were exposed to α-TOS for the durations and at the concentrations shown. They were assessed for the expression of c-IAP1 mRNA by RT-PCR (A), c-IAP1 protein by Western blotting (B), FLIP mRNA by RT-PCR (C) and FLIP protein by Western blotting (D). The images are representative of at least three independent experiments.

α-TOS augmented the activity of caspases

IAPs inhibit distinct members of the caspase family of cysteine proteases. Caspases facilitate apoptosis by cleaving a growing number of cellular targets18. FLIP is an inhibitor of caspase 819. We found that α-TOS suppressed c-IAP1 and FLIP expression in breast cancer cells expressing erbB2 (Figure 3), which led us to measure activation of caspase 3 and caspase 8. We found that MCF7 cells do not express caspase 3, which is consistent with results reported by Mathiasen20. Figure 4A shows that α-TOS induced an increase in caspase 8 activity in MCF7 cells. Figures 4B and 4C show that α-TOS increased the activity of caspase 3 and caspase 8 in MDA-MB-453 cells.

α-TOS augmented caspase activity. (A) MCF7 cells were treated with 100 μmol/L α-TOS for 0–12 h. Thirty micrograms of total protein were added to reaction buffer containing Ac-IETD-pNA (2 mmol/L) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The absorbance of yellow pNA cleaved from its corresponding precursor was measured using a spectrometer at 405 nm. (B), (C) MDA-MB-453 cells were incubated with 100 μmol/L α-TOS for 0–12 h. Thirty micrograms of total protein were added to reaction buffer containing Ac-DEVD-pNA (2 mmol/L) or Ac-IETD-pNA (2 mmol/L); the reaction was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, and the absorbance of yellow pNA cleaved from its corresponding precursor was measured using a spectrometer at 405 nm. The specific caspase activity, normalized to total protein of cell lysates, was then expressed as fold increase compared to baseline caspase activity in the control cells cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. bP<0.05 vs 0 h.

α-TOS induced apoptosis synergically with hrTRAIL

Although hrTRAIL is a potent anticancer agent, it has been reported that erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells are resistant to hrTRAIL21. Figures 5A and 5B show that hrTRAIL induced very low levels of apoptosis in MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells, indicating that both of these erbB2-expressing cell lines are resistant to hrTRAIL. However, both cell lines are sensitive to α-TOS treatment, which is consistent with results reported by Wang10, showing that α-TOS causes efficient apoptosis in breast cancer cells regardless of their erbB2 status. Figures 5A and 5B also demonstrate the synergism (or an additive effect) of α-TOS with hrTRAIL in both cell lines. To determine whether the expression of erbB2 was the major reason that cells had low susceptibility to hrTRAIL, we knocked down the level of erbB2 mRNA using erbB2/siRNA in MDA-MB-453 cells that express a higher level of erbB2 than MCF7 cells (Figure 5C). The results, shown in Figure 5D, demonstrate that knocking down the expression of erbB2 sensitized the cells to hrTRAIL-induced apoptosis.

α-TOS acted synergically with hrTRAIL in the induction of apoptosis in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells. MCF7 (A) and MDA-MB-453 (B) cells were treated with hrTRAIL (10 ng/mL or 30 ng/mL) and/or α-TOS (50 μmol/L) for the indicated durations. When we detected synergy between hrTRAIL and α-TOS, both reagents were added to the cells at same time. Apoptosis was assessed using the annexin V method and evaluated based on the percentage of annexin V-positive cells scored by FACS analysis. Data are shown as the mean values±SD (n=5−8). The symbol “b” indicates a significant difference in apoptosis in cells exposed to hrTRAIL+α-TOS vs cells exposed to hrTRAIL or α-TOS (bP<0.05). (C) MDA-MB-453 cells were evaluated by Western blotting for the expression of erbB2 after treatment with erbB2/siRNA for 24 and 48 h. (D) Induction of apoptosis in control MDA-MB-453 cells (1) and cells pretreated with non-silencing siRNA (2) or erbB2/siRNA (3) and exposed to 30 ng/mL hrTRAIL for 48 h. “e” Indicates a significant difference in hrTRAIL-induced apoptosis in cells pretreated with erbB2/siRNA vs cells pretreated with non-silencing siRNA (eP<0.05). The data are derived from three independent experiments and are presented as the mean values±SD.

α-TOS decreased the hrTRAIL-induced transient activation of NF-κB

More direct studies of NF-κB activation revealed that NF-κB was activated in MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 cells exposed to hrTRAIL. Figure 6 shows the substantial activation of NF-κB 30 min after the addition of hrTRAIL to the cells, although this activation was less pronounced than that caused by treatment with the strong NF-κB activator, TNF-α. This activation was transient and lasted for about 1 h, after which it declined. Pretreatment with α-TOS abolished the initial NF-κB activation observed with hrTRAIL alone.

α-TOS decreased the transient activation of NFκB caused by hrTRAIL. MCF7 (A) and MDA-MB-453 (B) cells were treated with α-TOS (50 μmol/L) and/or hrTRAIL (30 ng/mL) or TNF-α (100 U/mL), and washed with PBS. Nuclear proteins were prepared and probed for NFκB activation using the TransAMTM NFκB p65 kit. The level of NFκB activation (p65 binding to its cognate DNA sequence) is expressed as absorbance at 450 nm.

Discussion

In nonmalignant cells, the NF-κB transcription factor complexes (a heterotrimer usually composed of the p50 and p65 subunits bound to an inhibitor subunit, IκB) are largely cytoplasmic. Activation of NF-κB results in the proteasomal degradation of IκB and nuclear translocation of NF-κB. Activated NF-κB then binds to the cognate promoters of genes under its transcriptional control, resulting in their expression.

Activated NF-κB increases the expression of antiapoptotic genes, such as the caspase-inhibiting IAPs7 and FLIP8. Therefore, inhibition of NF-κB activation may be of great benefit by causing apoptosis in therapy-resistant cancer cells expressing erbB2. Therefore, we hypothesized that α-TOS inhibits NF-κB activation and promotes apoptosis of erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells. One of the reasons for this hypothesis was the finding that α-TOS causes apoptosis in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells10. Akazawa and colleagues22 also demonstrated that α-tocopheryloxybutyric acid, a compound analog to α-TOS, efficiently causes apoptosis in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells, although the mechanism by which this occurs was not clarified.

Our studies demonstrate that α-TOS inhibits the NF-κB pathway based on the following results: (1) α-TOS decreased p65 protein expression in the nuclear fraction of MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells (Figure 1C), (2) α-TOS suppressed activation (phosphorylation) of Akt in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells (Figure 2), (3) α-TOS suppressed c-IAP1 and FLIP expression in erbB2-positive breast cancer cells (Figure 3), and (4) α-TOS increased the activation of caspase 3 and caspase 8 in MDA-MB-453 cells and caspase 8 in MCF7 cells (Figure 4). The above results indicate that α-TOS inhibits the NF-κB pathway in the breast cancer cells with high (MDA-MB-453) and low (MCF7) expression of erbB2; these findings are consistent with a paper reporting the inhibition of NF-κB activation by α-TOS in the context of cardiovascular disease23.

hrTRAIL has been reported to selectively induce apoptosis in vitro and in vivo24, 25. A previous study showed that hrTRAIL-activated caspase 8 could generate the truncated Bid protein that triggers the release of cytochrome c (Cyt c) from mitochondria, leading to assembly of the apoptosome with the ensuing activation of effector caspases. Following the activation of caspase 8, TRAIL can also induce the direct activation of effector caspases26. In both cases, caspase 8 activation is inhibited when the expression of the FLIP protein was upregulated in cancer cells. While the mitochondria are involved in hrTRAIL-induced apoptosis, the IAPs, which are often upregulated in cancer cells, counteract the apoptogenic signals.

Although hrTRAIL is a potent anticancer agent, Matsuzaki et al12 reported that some tumor cells possess intrinsic or acquired resistance to hrTRAIL. Trauzold et al27 also demonstrated that the treatment of cells with hrTRAIL resulted in strongly increased distant metastasis of pancreatic tumors in vivo. Consistent with these results, we show here that MCF7 and MDA-MB-453 cells were relatively resistant to hrTRAIL-induced apoptosis (Figure 5).

We also document synergy between α-TOS and hrTRAIL in MDA-MB-453 and MCF7 cells (Figure 5). These results are consistent with previous studies in colon cancer cells28, in which synergy between hrTRAIL and α-TOS was reported. Similarly, a synergistic effect of hrTRAIL and α-TOS has been observed in mesothelioma cells14. Here, our results indicate that α-TOS decreased the transient activation of NF-κB caused by hrTRAIL, which may be the molecular mechanism of synergy between hrTRAIL and α-TOS. Dalen and Neuzil16 have shown that α-TOS sensitizes cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through inhibition of NF-κB activation. Another publication suggested that the synergy between α-TOS and hrTRAIL occurs through promotion of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway28. The inhibition of NF-κB activation by α-TOS has a pro-apoptotic effect that can also be implicated in adjuvant cancer therapy.

Previous studies have shown that α-TOS triggers apoptosis in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cells by signaling via the mitochondrial pathway10, 29. α-TOS induces dissipation of the mitochondrial inner membrane potential and the release of mitochondrial apoptotic proteins such as AIF, Smac/Diablo and Cyt c. In many cases, relocation of Cyt c leads to formation of the apoptosome, a complex consisting of Cyt c, Apaf-1 and procaspase 9, with the ensuing activation of caspase 9 followed by activation of caspase 317, 29.

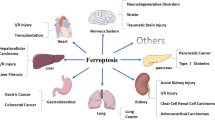

The data shown in this paper and supported by other reports point to the following mechanism by which α-TOS can overcome the resistance to apoptosis of cancer cells expressing erbB2 (Figure 7). α-TOS suppresses erbB2-dependent activation of NF-κB, possibly via inhibition of erbB2 auto-activation, as shown elsewhere22 , which would then lead to inhibition of activation of the central pro-survival factors Akt and/or NF-κB. Ultimately, this would cause lower levels of expression of the caspase inhibitors FLIP and IAPs, induction of apoptosis by α-TOS and sensitization of cancer cells to other inducers of apoptosis (Figure 7).

Possible molecular mechanisms by which α-TOS overcomes the resistance of erbB2-expressing cells to apoptosis and sensitizes them to hrTRAIL-induced apoptosis. Expression of erbB2 leads to the activation of the central survival protein, Akt. The kinase then activates a variety of substrates, including NFκB, which causes increased expression of the caspase inhibitor, FLIP, and IAPs, which inhibit both death receptor-mediated (extrinsic) or mitochondria-dependent (intrinsic) apoptosis. We propose that α-TOS suppresses the activation of NFκB by a mechanism that may include the inhibition of erbB2, PI3K, or Akt activation. This inhibition results in the decreased expression of FLIP and IAPs and in the initiation of apoptotic signaling by α-TOS and the sensitization of cells to hrTRAIL-mediated apoptosis. C3, C8, and C9: caspase 3, caspase 8, and caspase 9, respectively.

Author contribution

Xiu-fang WANG designed the experiments and wrote the paper; Xiu-fang WANG, Ying XIE, Yuan ZHANG, Hong-gang WANG, Zhan-jun LU, and Xiao-cui DUAN performed the research and analyzed the data.

References

Roskoski R . The ErbB/HER receptor protein-tyrosine kinases and cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004; 319: 1–11.

Jarvinen TA, Liu ET . Simultaneous amplification of Her (ErbB2) and topoisomerase IIα (TOP2A) genes in combination therapy in cancer. Curr cancer drug targets 2006; 6: 579–602.

Ward SG, Finan P . Isoform-specific phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors as therapeutic agents. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2003; 3: 426–34.

Chang F, Lee JT, Navolanic PM, Steelman LS, Shelton JG, Blalock WL, et al. Involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and neoplastic transformation: a target for cancer chemotherapy. Leukemia 2003; 17: 590–603.

Kane LP, Shapiro VS, Stokoe D, Weiss A . Induction of NF--κB by the Akt/PDK kinase. Curr Biol 1999; 9: 601–4.

Shukla S, Maclennan GT, Marengo SR, Resnick MI, Gupta S . Constitutive activation of PI3K-Akt and NF-kappaB during prostate cancer progression in autochthonous transgenic mouse model. Prostate 2005; 64: 224–39.

LaCasse EC, Baird S, Korneluk RG, MacKenzie AE . The inhibitors of apoptosis protein (IAPs) and their emerging role in cancer. Oncogene 1998; 17: 3247–59.

Kim KM, Lee YJ . Amiloride augments TRAIL-induced apoptotic death by inhibiting phosphorylation of kinases and phosphatases associated with the P13KAkt pathway. Oncogene 2005; 24: 355–66.

Neuzil J, Tomasetti M, Mellick AS, Alleva R, Salvatore BA, Birringer M, et al. Vitamin E analogues: A new class of inducers of apoptosis with selective anti-cancer effect. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2004; 4: 267–84.

Wang XF, Witting PK, Salvatore BA, Neuzil J . Vitamin E analogs trigger apoptosis in HER2/erbB2-overexpressing breast cancer cells by signaling via the mitochondrial pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 326: 282–9.

Gliniak B, Le T . Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand's anti-tumor activity in vivo is enhanced by the chemotherapeutic agent CPT-11. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 6153–8.

Matsuzaki H, Schmied BM, Ulrich A, Standop J, Scheider MB, Batra SK, et al. Combination of tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and actinomycin D induces apoptosis even in TRAIL-resistant human pancreatic cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 2001; 7: 407–14.

Bernard D, Quatannens B, Vandenbunder B, Abbadie C . Rel/NF--κB transcription factors protect against tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis by up-regulating the TRAIL decoy receptor DcR1. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 27322–8.

Tomasetti M, Rippo MR, Alleva R, Moretti S, Andera L, Neuzil J, et al. α-Tocopheryl succinate and TRAIL selectively synergise in induction of apoptosis in human alignant mesothelioma cells. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 1644–53.

Wang XF, Birringer M, Dong LF, Veprek P, Low P, Swettenham E, et al. A peptide conjugate of vitamin E succinate targets breast cancer cells with high erbB2 expression. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 3337–44.

Dalen H, Neuzil J . α-Tocopheryl succinate sensitises T lymphoma cells to TRAIL killing by suppressing NF--κB activation. Br J Cancer 2003; 88: 153–8.

Weber T, Dalen H, Andera L, Nègre-Salvayre A, Augé N, Sticha M, et al. Mitochondria play a central role in apoptosis induced by α-tocopheryl succinate, an agent with anticancer activity: comparison with receptor-mediated pro-apoptotic signaling. Biochemistry 2003; 42: 4277–91.

Holcik M . The IAP proteins. Trends Genet 2002; 18: 537–8.

Kataoka T, Budd RC, Holler N, Thome M, Martinon F, Irmler M, et al. The caspase-8 inhibitor FLIP promotes activation of NF kappaB and Erk signaling pathway. Curr Biol 2000; 10: 640–8.

Mathiasen IS, Lademann U, Jäättelä M . Cancer Res 1999; 59: 4848–56.

Liu N, Zhang J, Zhang J, Liu S, Liu Y, Zheng D . Erbin-regulated sensitivity of MCF-7 breast cancer cells to TRAIL via ErbB2/AKT/NF-kappaB pathway. J Biochem 2008; 143: 793–801.

Akazawa A, Nishikawa K, Suzuki K, Asano R, Kumadaki I, Satoh H, et al. Induction of apoptosis in a human breast cancer cell overexpressing ErbB-2 receptor by α-tocopheryloxybutyric acid. Jpn J Pharmacol 2002; 89: 417–21.

Erl W, Weber C, Wardemann C, Weber PC . α-Tocopheryl succinate inhibits monocytic cell adhesion to endothelial cells by suppressing NF-κB mobilization. Am J Physiol 1997; 273: H634–40.

Bonavida B, Ng CP, Jazirehi A, Schiller G, Mizutani Y . Selectivity of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis of cancer cells and synergy with drugs: the trail to nontoxic cancer therapeutics. Int J Oncol 1999; 15: 793–802.

French LE, Tschopp J . The TRAIL to selective tumor death. Nat Med 1999; 5: 146–7.

Zou H, Li Y, Liu X, Wang X . An APAF-1·cytochrome c multimeric complex is a functional apoptosome that activates procaspase-9. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 11549–56.

Trauzold A, Schniewind B, Egberts J . TRAIL promotes metastasis of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 2006; 25: 7434–9.

Weber T, Lu M, Andera L, Lahm H, Gellert N, Fariss MW, et al. Vitamin E succinate is a potent novel antineoplastic agent with high tumor selectivity and cooperativity with tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL, Apo2L) in vivo. Clin Cancer Res 2002; 8: 863–9.

Wang XF, Dong LF, Zhao Y, Tomasetti M, Wu K, Neuzil J . Vitamin E analogues as anti-cancer agents: lessons from studies with α-tocopheryl succinate. Mol Nutr Food Res 2006; 50: 675–85.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds from the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (No 30873001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Xf., Xie, Y., Wang, Hg. et al. α-Tocopheryl succinate induces apoptosis in erbB2-expressing breast cancer cell via NF-κB pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin 31, 1604–1610 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2010.171

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2010.171

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The interrelationship between HER2 and CASP3/8 with apoptosis in different cancer cell lines

Molecular Biology Reports (2014)

-

TRAIL and vitamins: opting for keys to castle of cancer proteome instead of open sesame

Cancer Cell International (2012)

-

(+)α-Tocopheryl succinate inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I and is as effective as arsenic trioxide or ATRA against acute promyelocytic leukemia in vivo

Leukemia (2012)