Abstract

Poor electrocatalytic activity and carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning of the anode in Pt-based catalysts are still two major challenges facing direct methanol fuel cells. Herein, we demonstrate a highly active and stable Pt nanoparticle/Mo2C nanotube catalyst for methanol electro-oxidation. Pt nanoparticles were deposited on Mo2C nanotubes using a controllable atomic layer deposition (ALD) technique. This catalyst showed much higher catalytic activity for methanol oxidation and superior CO tolerance, when compared with those of the conventional Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts. The experimental evidence from X-ray absorption near-edge structure spectroscopy and scanning transmission X-ray microscopy clearly support a strong chemical interaction between the Pt nanoparticles and Mo2C nanotubes. Our studies show that the existence of Mo2C not only minimizes the required Pt usage but also significantly enhances CO tolerance and thus improves their durability. These results provide a promising strategy for the design of highly active next-generation catalysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Direct methanol fuel cells have attracted much attention for portable power applications because of their distinctive advantages of high-energy density and the ready availability, inexpensiveness and the safe storage and transportation potential of methanol as a liquid fuel.1, 2, 3 Despite these advantages, a few technological obstacles remain to be circumvented before commercial applications can be achieved. One main challenge is the poor electrocatalytic activity in the methanol oxidation reaction (MOR); another is the occurrence of serious carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning at the anode of the Pt catalyst. A promising strategy for addressing these challenges is to alloy Pt with other oxophilic elements such as Ru,4, 5, 6, 7 Mo8, 9, 10, 11 and Sn.12 Traditionally, nanoparticles of Pt and its alloys with Ru are selected as the best catalyst owing to their relatively high activity and durability for MOR. However, the high price of Pt and Ru makes them less attractive in practical applications. Alternatively, increasing the activity per unit area and achieving a high dispersion of the active component could markedly increase the catalytic activity and decrease the necessary amount of the expensive component.13, 14 To this end, atomic layer deposition (ALD) is an attractive technique to deposit such thin films or nanosized catalysts because of its merits of simplicity, reproducibility and conformality.15, 16, 17, 18 Another effective strategy to improve the catalytic activity of the noble metal-based catalyst is using suitable catalyst promoter.19, 20, 21 The addition of carbide could lead to a highly promotive effect on noble metal-based electrocatalysts,22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 which has been described as synergistic effects. Recently, Mo2C has been used as an anode material for the direct oxidation of hydrocarbons in fuel cells and has shown promising performance.21, 28, 29

Herein, we show that Pt nanoparticles deposited on Mo2C nanotubes using ALD is an efficient and synergistic catalyst for methanol electro-oxidation. Our strategy is to improve the electron transport by means of the metallic property of one-dimensional (1D) Mo2C nanotube, alleviate the oxidation of Pt naoparticles by interaction with the Mo2C support and provide an OH reservoir for the MOR by controlled formation of molybdenum oxide (MoOx) layer on the surface of Mo2C nanotubes. Remarkably, this Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst showed much higher catalytic activity for methanol oxidation and superior CO tolerance when compared with that of the conventional Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts, which is very important for improving their long-term durability and achieving the commercialization of direct methanol fuel cells. Extended X-ray absorption near-edge structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy and scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) analysis both support a strong chemical interaction between the Pt nanocrystals and Mo2C nanotubes. These results show that the existence of Mo2C not only minimizes the required Pt usage but also significantly enhances CO tolerance and thus improves durability.

Materials and methods

Materials synthesis

Branched polyaniline/MoO3 nanostructures were used as precursors to synthesize the hollow Mo2C nanorods. A detailed description of this process is provided in our previous work.30. In a typical synthesis, 0.15 g of α-MoO3 nanorods was dispersed in 100 ml of 1 M HCl solution by sonication treatment and then cooled to –5 °C while stirring. A measure of 0.3 ml of aniline was dissolved in 100 ml of 1 M HCl and then transferred to a beaker containing a solution of ammonium persulfate (0.5 g) in 100 ml of 1 M HCl. The above mixture was cooled to –5 °C, then transferred to the nanorod suspension and kept at the temperature for 24 h while stirring. The final precipitate was washed with distilled water and ethanol, and then dried at 40 °C for 24 h. The hollow Mo2C nanotubes were obtained by calcining the branched polyaniline/MoO3 at 850 °C for 2 h under 10%H2/Ar flow.

ALD deposition of Pt nanoparticles on Mo2C nanotubes

Platinum nanoparticles were deposited on Mo2C nanotubes via thermal ALD (LabNano; TMSeries, Beijing, China). The container of Mo2C nanotubes was placed inside the reactor directly on the heated stage of the ALD instrument. The deposition temperature was 250 °C, while the container for the Pt precursor was kept at 65 °C to provide a steady-state flux of MeCpPtMe3 ((methylcyclopentadienyl)-trimethylplatinum) to the reactor (ca. 400 mTorr at 65 °C). Gas lines were held at 150 °C to avoid condensation of the precursor. High-purity O2 (99.999%) was used as the counter-reactant, and high-purity N2 (99.995%) was used both as a purging gas and carrier gas. In each ALD cycle, a 1 s MeCpPtMe3 pulse and a 1 s of O2 pulse were separated by 20 s of N2 purge. The Pt loading on Mo2C nanotubes was thus accurately controlled by the number of ALD cycles.

Characterization

X-ray diffraction analyses were performed on an X’Pert Pro diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ=1.54 Å). High-resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and electron energy loss spectroscopy measurements were carried out on JEOL ARM200F transmission electron microscopy (TEM) operated at 200 kV (JEOL, Peabody, MA, USA). BET surface area and pore volumes were tested using a Quantachrome Instruments NOVA4000 (Boynton Beach, FL, USA) after the samples were vacuum dried at 300 °C over 5 h. The Pt loading of the catalysts was analyzed using induced coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA).

Electrochemical measurements

For comparison, the commercial Pt/C (Hispec 3000), PtRu/C and Pt-black catalysts were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA). The loading amounts of various noble metals were shown in Supplementary Table S1. The working electrodes were prepared as follows. Typically, catalyst dispersions were prepared by mixing 3 mg of the catalyst powder in 3 ml ethanol solution containing 0.05 wt% Nafion solution, followed by 10 min ultrasonication. The glassy carbon disk electrodes (5 mm diameter, 0.196 cm2 surface area; Pine Research Instrumentation) served as the substrate and were polished to a mirror finish. Ten microliters of the catalyst suspension was pipetted onto the glassy carbon disk substrate. The resulting catalyst films were dried under flowing N2 at room temperature. The electrochemical properties of the catalysts were tested on a VMP3 potentiostat (Bio-Logic SA, Claix, France) and rotating disk electrode (M636; Pine Research Instrumentation) using a three-electrode system consisting of a glassy carbon rotating disk electrode, a Pt wire counter electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) reference electrode. For convenience, all potentials in this study are referenced to the SCE. The working electrode was first cycled between −0.241 and 0.959 V at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1 for 50 times in an Ar-purged H2SO4 solution (0.5 M) at room temperature until a clean electrode surface was obtained. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were also conducted by cycling the potential between −0.241 and 0.959 V, with a sweep rate of 100 mV s−1. For the MOR, CVs were measured in an aqueous solution containing 0.5 M CH3OH and 0.5 M H2SO4 at room temperature, with a sweep rate of 100 mV s−1. For CO stripping voltammetry, pure CO (99.99%) gas was bubbled into the solution (in a fume hood) at a position close to the working electrode for 1 s to 5 min, with the electrode polarized at −0.191 V vs SCE. The excess CO was removed by purging with Ar for 30 min under potential control, followed by CO stripping at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. Accelerated durability tests were performed in an Ar-purged 0.5 M H2SO4 solutions at a sweep rate of 100 mV s−1 for 5000 cycles. Chronoamperometry measurements were performed in a 0.5 M H2SO4 and 0.5 M CH3OH solution after a 100-cycle CV activity in an Ar-purged 0.5 M H2SO4 solution with a sweep rate of 100 mV s−1. The detailed procedures are as follows. The glassy carbon electrode loaded with ALD600Pt/Mo2C catalyst was held at 0.509 V (vs SCE) for 1.0 s to oxidize completely any adsorbates to obtain a clean surface. The potential was then stepped negatively to −0.441 V (vs SCE) and kept for 5 s to recover the solution near electrode surface. Finally, the potential was kept at 0.359 V (vs SCE) to oxidize methanol and transient current–time (0–100 s) curve of CH3OH oxidation was recorded. After a 5000-cycle accelerated durability test, chronoamperometry measurements were also performed using the above procedures.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy

The Pt L3-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurements were performed on the 06ID-1 superconducting wiggler-sourced hard X-ray microanalysis (HXMA) beamline at the Canadian Light Source with a premirror–double-crystal monochromator–postmirror configuration using Si(1 1 1) crystals and Rh mirrors. During data collection, the Canadian Light Source 2.9 GeV ring was operated with a 250 mA injection current and the beamline wiggler running at 1.9 T. Measurements were made at room temperature in transmission mode for the Pt foil and Pt/C samples (ion chambers filled with 20% Ar and 80% He), and in fluorescence mode for the ALD system (using a 32-element Ge detector). Data acquisition was performed at 10 eV per step, 0.5 eV per step and 0.05 Å−1 per step for the pre-edge, X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and EXAFS regions, respectively. The second crystal of the monochromator was detuned to 60% during the data collection to suppress higher harmonic components of the incident radiation. The L3-edge of a Pt foil reference was used for energy calibration purposes. The Pt L3-edge XANES as well as Pt L3-edge EXAFS were recorded for analysis. The software package ATHENA (version 0.8.056) was used for data reduction of the XANES spectra. WinXAS (version 3.1) was used to perform the R-space fitting for the Fourier-transformed Pt L3-edge spectra using scattering paths generated by FEFF (version 8.2).

STXM measurements

For STXM measurements, powder samples of the Mo2C nanotubes, ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotubes and commercial Pt/C catalyst were dispersed in methanol by brief sonication and then deposited onto Si3N4 windows and allowed to dry in air. In addition, powder samples directly deposited onto Si3N4 windows without solvent dispersion were prepared for comparison. STXM was conducted at the SM beamline of the Canadian Light Source, a 2.9 GeV third-generation synchrotron facility. The X-ray source is an APPLE II-type elliptically polarizing undulator, which can provide arbitrary polarization. Circularly polarized light was used to average-out the in-plane polarization dependence of the X-ray absorption. In STXM, the monochromatic X-ray beam is focused by a Fresnel zone plate to an ~30 nm spot on the sample, and the sample is raster-scanned with synchronized detection of transmitted X-rays to generate image sequences (stacks) over a range of photon energies. Image stacks at the C K-edge and Mo L3-edge were acquired. STXM data were analyzed using the freeware program aXis2000 (http://unicorn.mcmaster.ca/aXis2000.html). Spatially resolved XANES spectra for different regions of interest were extracted from the aligned image stacks using image masks. More details of the STXM experimental and data analysis procedures can be found elsewhere.31, 32

Results and discussion

Physical characterization

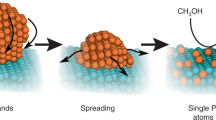

Platinum was deposited on Mo2C nanotubes using ALD with MeCpPtMe3 (Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA; purity 98%) and oxygen (99.999%) as precursors, and nitrogen (99.9995%) as a purging gas. A schematic diagram describing the deposition mechanism of Pt nanoparticles using ALD on Mo2C nanotubes is shown in Figure 1.

The phase purity and crystal structure of the products obtained were examined by X-ray diffraction. Supplementary Figure S1 (Supporting information) shows that the as-prepared product is orthorhombic Mo2C (JCPDS file no. 79-0744). The morphology and structure of the Mo2C nanotubes were characterized by high-resolution TEM. TEM analysis of an Mo2C particle reveals a porous nanotube morphology containing some few nanoparticles, as shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Supplementary Figure S3 shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and the corresponding Barret–Joner–Halenda pore size distribution curves of the obtained Mo2C nanotubes. It also shows an IV-type adsorption–desorption isotherm with H4-type hysteresis,33 a feature of mesoporous materials. The Mo2C nanotubes were found to have a large Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) area of 90.73 m2 g−1. The average pore diameter is 3.59 nm, calculated from the desorption branch of the nitrogen isotherm obtaining using the Barret–Joner–Halenda method, and the corresponding Barret–Joner–Halenda desorption cumulative volume is 0.20 cm3 g−1.

The size and loading amount of Pt nanoparticles on the Mo2C nanotubes could be easily tuned by controlling the cycle numbers of ALD. Figures 2a and b show the bright field STEM images at different magnification of Pt nanocrystals on Mo2C nanotubes with 600 deposition cycles. It can be seen that Pt nanoparticles of ca. 2–6 nm in diameter were homogeneously distributed on the Mo2C nanotubes. Figure 2c is an HAADF (high annular dark-field)-STEM image of an individual Pt nanoparticle. The interplanar spacing of the lattice fringe marked in Figure 2c is 0.225 nm, which is consistent with the (1 1 1) lattice plane of Pt. The weight percentage of Pt in the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotubes is 13.90% as determined by induced coupled plasma measurement.

Electrochemical performance

The electrocatalytic properties of Pt/Mo2C nanotubes were evaluated and compared with the commercial Pt-black, Pt/C and PtRu/C electrocatalysts. A better catalyst is typically characterized by a more negative MOR onset potential and higher methanol oxidation peak current density. The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) of Pt was estimated by measuring the charge (QH) associated with hydrogen underpotential deposition (Hupd) adsorption/desorption region after double-layer correction and assuming a value of 210 μC cm2 for the adsorption of a monolayer of hydrogen on the Pt surface.34 The determined ECSA of the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotubes, the commercial Pt-black, Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts are 31.52, 20.94, 77.72 and 65.51 m2 g−1, respectively, as shown in Supplementary Figure S4. The lower ECSA of the Pt/Mo2C nanotubes relative to the commercial Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts may originate in part from the MoOx layer on the surface of Mo2C nanotubes (formed during the preparation process of the Mo2C nanotubes), as evidenced by electron energy loss spectroscopy analysis (Supplementary Figure S2c). On the one hand, this MoOx layer was enhanced by the ALD process, which could have further decreased the ECSA of Pt/Mo2C.35 On the other hand, the MoOx layer on the surface of Mo2C nanotubes favors the adsorption of OH in solution and acts as a nanostructured OH reservoir for the MOR; thus, it is able to remarkably enhance the catalytic activity. It is worthwhile to note that the benefit from MoOx is observed only when the amount of MoOx is properly maintained so that the Pt–MoOx interface is formed without causing a significant reduction in the ECSA of Pt.35

We first examined the catalytic activities of the ALD Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalysts with different Pt deposition cycles, as shown in Supplementary Figure S6. The CVs of the electrodes with different catalyst materials were tested in 0.5 M H2SO4 and 0.5 M CH3OH solutions and the current densities were normalized to the ECSA of Pt. Analysis of these data revealed that the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst showed the best catalytic activity among various samples studied; thus, the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst was chosen for comparison with the commercial Pt-black, Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts. As shown in Figure 3, the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst possesses a significantly more negative MOR onset potential (ca. −0.15 V) than the commercial Pt-black, Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts (ca. −0.15 V). The negative shifts of the onset and forward scan peak potentials indicate that the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst can markedly reduce the overpotential for methanol oxidation. Furthermore, the peak current density shows that the catalytic activity of the ALD600Pt/Mo2C catalyst for the MOR is higher than that of the commercial PtRu/C, Pt/C and Pt-black catalysts (2.90, 1.58 and 1.46 times, respectively), as shown in Supplementary Table S2. It is generally understood that the anodic peak in the reverse scan to be linked to the removal of incompletely oxidized carbonaceous species accumulated on the catalyst surface during the forward anodic scan.2, 36 CO is an intermediate species of methanol oxidation and can poison the Pt catalyst, leading to a lower fuel cell potential and energy conversion efficiency.2 Therefore, the ratio of the forward anodic peak current density to the backward anodic peak current density (If/Ib) can be used to indicate the CO tolerance of the catalyst.36, 37, 38, 39 A low If/Ib value usually indicates poor oxidation of methanol to CO2 during the forward anodic scan and excessive accumulation of residual carbon species (for example, CO) on the catalyst surface. Conversely, a higher If/Ib ratio is indicative of improved CO tolerance and increase methanol oxidation. For the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst, a much higher If/Ib value (1.71) was observed relative to that of the commercial Pt-black (0.99), Pt/C (0.85) and PtRu/C (1.33), which suggests that methanol can be more efficiently oxidized on this catalyst during the forward scan and has a much better CO tolerance. In a control experiment, the electrocatalytic properties of Mo2C nanotubes with Pt nanoparticles deposited using sodium borohydride reduction were also tested. The HAADF-STEM images of the prepared catalyst are shown in Supplementary Figures S5 and S6, which reveal that the Pt nanoparticles were significantly aggregated. Although this catalyst had a higher Pt loading amount of 16.2 wt%, it showed poor catalytic activity compared with the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotubes, as shown in Supplementary Figure S7. This demonstrates the advantage of the ALD deposition technique. Supplementary Figure S8 shows the cyclic voltammograms of the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotubes, the pristine Mo2C nanotubes and the commercial Pt-black catalysts in a 0.5 M H2SO4 and 0.5 M CH3OH solution, which clearly indicates a synergistic effect between Pt and Mo2C and further confirmed by the later X-ray absorption fine structure studies. Therefore, the enhancement of the catalytic activity of the ALD Pt/Mo2C nanotubes may be attributed to high dispersion of the Pt nanoparticles, the unique microstructure of Pt/Mo2C nanotubes and the synergetic effect of Pt nanoparticles and Mo2C nanotubes.

The enhanced MOR activity and CO tolerance of the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst was further studied with CO stripping voltammetry performed as a function of CO poisoning time in 0.5 M H2SO4 at room temperature. It was also compared with the commercial PtRu/C catalyst, which is state-of-the-art catalyst for use in direct methanol fuel cells. Figure 4 shows the CO stripping voltammograms for the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst and the commercial PtRu/C catalyst. A CO oxidation peak was observed for the commercial PtRu/C catalyst around 0.60 V after purging with pure CO gas for 1 s, and the equilibrium CO coverage was reached within 5 s. However, for the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst, CO oxidation peak appeared at about 0.62 V and the equilibrium CO coverage was reached after 2 min. This result indicates that the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst have superior CO tolerance relative to the conventional PtRu/C catalyst.

The stability of the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube catalyst for methanol oxidation was examined by repeating electrochemical reaction scans in a 0.5 M H2SO4/0.5 M CH3OH solution for 5000 cycles. As shown in Supplementary Figures S9a–S12a and Supplementary Table S2, the ECSA of the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotubes dropped by 50.70% after 5000 cycles, whereas those of the commercial Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts were reduced by 76.30% and 74.03%, respectively. Correspondingly, the forward scan peak current density of the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotubes dropped only 39.05% after the stability test, whereas those of the commercial Pt-black, Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts decreased 46.46%, 71.95% and 75.37%, respectively. The detailed comparison of decay rate of the catalytic activities with CV cycles for the ALD600Pt/Mo2C catalyst as well as the commercial Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts is shown in Supplementary Figure S13 and Supplementary Table S3. All of the aformentioned experiments unequivocally show that the ALD600Pt/Mo2C nanotube has better durability than that of the commercial state-of-the-art Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts.

X-ray absorption fine structure studies

The interaction of the catalytically active clusters (for example, Pt nanoparticles) with the support often results in a change in the electronic properties of the atoms close to the cluster–support interface.40 The synergistic effect between the Mo2C nanotubes and Pt was thus studied by X-ray absorption spectra. XANES spectroscopy is a powerful technique widely used in studying the electronic and chemical structure of materials.41, 42 Information about the valence state of the Mo and its electron configuration in the Pt/Mo2C can be obtained from the XANES region of the Mo L3-edge absorption spectra. Figure 5 shows the experimental Mo L3-edge XANES of the ALD Pt/Mo2C nanotube samples, together with the pristine Mo2C nanotubes and MoO3 for comparison. Analysis indicates that MoOx is formed on the surface of Mo2C nanotubes and that the Pt ALD process results in intensification of the MoOx feature. This oxide layer provides a suitable site for the chemical interaction between the Mo2C nanotubes and Pt nanoparticles.

Figure 6a shows the experimental Pt K-edge XANES of the ALD Pt/Mo2C nanotube sample, Pt foil and the commercial Pt/C catalyst used for comparison. It is apparent that the spectra for Pt in the ALD Pt/Mo2C nanotube sample closely resemble those of the Pt foil, indicating largely metallic structure. The Pt/C reference catalyst, however, exhibits relatively greater white line intensity; this result has also been observed previously in the same material, and is attributed to a significant degree of Pt oxidation.43 The corresponding Fourier-transformed EXAFS spectra are also presented for comparison in Figure 6b. Qualitatively, peaks due to Pt–C/O and Pt–Pt/Mo scattering paths were observed near 1.6 and 2.7 Å, respectively, which also shows chemical interaction between the Mo2C nanotubes and Pt nanoparticles. To obtain more quantitative information regarding local structure, EXAFS fitting of the data was performed.

Parameters obtained from the aforementioned fits are presented in Table 1. In addition to the metallic Pt–Pt bonds expected for the Pt nanoparticles, peaks indicative of Pt bonding with C, O and Mo were observed. Based on the structure of the catalysts, these peaks were attributed to strong interactions between Pt and the Mo2C nanotube support materials, which unveils the origin of synergistic electrochemical activity of Pt nanoparticles/Mo2C nanotube catalyst. As is often in the case in EXAFS analyses, C and O could not be distinguished from one another in these fits because of their very similar atomic sizes and scattering properties; thus, they were included in a single scattering path (labeled Pt–C/O). The lower Pt–Pt coordination number (CN) in the ALD600Pt/Mo2C sample relative to the Pt foil is because of an increased proportion of surface Pt sites due to their nanoscale size. The Pt–Pt CN of the Pt/C catalyst, however, is anomalously low compared with values reported elsewhere in the literatures,43, 44 and does not make sense for metallic Pt nanoparticles. It is possible that a significant amount of Pt either remained unreduced during formation of the Pt/C catalyst or was subsequently reoxidized postsynthesis; this interpretation is also supported by the greater white line intensity of the Pt/C sample, which, as discussed previously, is indicative of Pt oxidation. The significantly enhanced catalytic activity of the ALD Pt/Mo2C nanotube sample could thus be explained at least in part by its relatively greater content of metallic Pt.

STXM using a nanoscale-focused soft X-ray beam provides excellent information regarding both chemical speciation and electronic structure, while also allowing for microscopic examination of individual nanomaterials.31, 32 STXM was thus used to investigate the chemical, electronic and structural nature of Pt nanocrystals deposited on Mo2C nanotubes via spatially resolved XANES spectroscopy and chemical imaging. Figures 7 and 8 present STXM characterization of bare ALD600Pt/Mo2C, and methanol-adsorbed ALD600Pt/Mo2C and Mo2C after dispersion in (and deposition from) methanol, at the C K-edge and Mo L3-edge, respectively. For the C K-edge spectra, due to the low penetration depth of soft X-rays, well-separated individual particles were sampled. The C K-edge absorption, or optical density (OD), images of the samples are shown in Figures 7a–c, and depict similar tube morphologies among the samples. The STXM spatial resolution is not sufficient to resolve individual Pt nanoparticles on the tubes, but spatially resolved XANES extracted from the individual tubes are able to deliver detailed chemical and electronic structural information, as shown in Figure 7d. First, the C K-edge of Pt/Mo2C shows elevated intensity relative to Mo2C due to Pt N-edge absorption, which supports the presence of Pt on the Mo2C tubes as well as a chemical interaction between the Mo2C nanotubes and Pt nanoparticles. Second, the C K-edge jumps (the OD difference between 280 and 320 eV, which is proportional to carbonaceous material thickness) of 0.42 and 0.58 OD for Pt/Mo2C (green line) and Mo2C nanotubes (blue line), respectively, are nearly double that of the bare Pt/Mo2C (0.26 OD) (red line), demonstrating a strong affinity for methanol adsorption. Furthermore, bare Pt/Mo2C comprised of a significant amount of sp2 carbon (good for electronic conductivity, and indicated by π*C=C at 285.5 eV) and carbide (at ~287.7 eV).45 After methanol adsorption, Pt/Mo2C shows significantly enhanced intensity in the carbide region owing to contributions of the σ*C–H (287.4 eV) from physically adsorbed methanol;46 the maximum intensity also up-shifts to 288.2 eV, suggesting a chemical adsorption of methanol onto Pt and formation of carbonyl-like groups or structures.46 The adsorption of a methanol molecule is important step for MOR. As for Mo2C, the enhanced intensity is still near the carbide region, suggesting a primarily physical adsorption of methanol on pure Mo2C. Although subtle, the above spectroscopic differences clearly illustrate the important role of Pt in the composite catalyst.

Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) C K-edge optical density images of (a) ALD600Pt/Mo2C, (b) ALD600Pt/Mo2C/methanol and (c) Mo2C/methanol. Images were averaged from all stack images at the C K-edge; the enclosed color lines indicate the regions of interest on the samples for extracting X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra; (d) C K-edge spatially resolved XANES spectra from the selected regions of interest in (a–c). Vertical dashed lines in the figures indicate spectral regions of interest. ALD, atomic layer deposition.

Mo L3-edge scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) optical density image of (a) ALD600Pt/Mo2C, (b) ALD600Pt/Mo2C/methanol and (c) Mo2C/methanol. Images were averaged from all stack images at the Mo L3-edge; the enclosed color lines indicate the regions of interest on the samples for extracting X-ray absorption-near edge structure (XANES) spectra, whereas the white arrows show nanotubes more heavily coated with Pt; (d) spatially resolved Mo L3-edge XANES spectra from the selected regions of interest in (a–c). Vertical dashed lines in the figures indicate spectral regions of interest. ALD, atomic layer deposition.

Owing to greater depth penetration of higher-energy X-rays at the Mo L3-edge, more concentrated samples were required to achieve data with sufficient signal/noise ratio. The OD images of the samples at the Mo L3-edge shown in Figures 8a–c reveal uniform Pt/Mo2C and Mo2C nanotubes, with a few of those being more heavily coated with Pt (indicated by white arrows in Figures 8a and b), as confirmed by strong X-ray absorption due to the Pt M-edge. The local XANES spectroscopy from a collection of individual nanotubes was extracted from the STXM Mo L3-edge stacks, as shown in Figure 8d. As in Figure 5, a chemical shift to higher energy from Mo2C to Pt/Mo2C is indicated, although apparently not due to methanol; this is consistent with the above conclusion that MoOx was formed on the surface of Mo2C during Pt deposition.

With regard to the mechanism of methanol electro-oxidation, it is generally believed that the reaction proceeds via several steps, wherein the first step (the adsorption of a methanol molecule) is immediately followed by dissociation of the molecule into several adsorbed species.9, 47 For conventional MOR catalysts, the function of Pt–Ru for catalytic methanol oxidation is commonly described via a ‘bifunctional mechanism’. The dissociative chemisorption of methanol is accomplished on platinum, whereas an oxyhydroxide forms on ruthenium and is responsible for the oxidation of the carbonaceous adsorbate (for example, methanol) to CO2.5, 6

In this work, the Pt nanoparticles/Mo2C nanotube catalyst outperforms the commercial Pt/C and PtRu/C catalysts even with a lower platinum loading, which can be attributed to several key reasons. First, the Pt nanoparticles on Mo2C nanotubes synthesized via the controlled ALD process were dispersed and exhibited smaller particle sizes relative to the commercial Pt/C catalyst. Second, Mo2C has a higher affinity for the methanol reactant than Pt/C (as revealed by STXM results) and has been demonstrated via EXAFS fitting analysis to interact strongly with the Pt nanoparticles. Third, in the presence of platinum, Mo2C nanotubes may have an active role in the electrochemical MOR, as reported by Shropshire48 and Kita et al.11 The formation of hydroxyl groups from water activation is essential for the removal of CO poisoning from the surface; this role, played by ruthenium in the conventional PtRu/C catalysts, can also be filled by Mo2C. The MoOx layer on the surface of Mo2C nanotubes favours the adsorption of OH in solution and acts as a nanostructured OH reservoir for the MOR. Thus, the Mo2C nanotube-based catalysts exhibit enhanced CO tolerance. Fourth, one-dimensional Mo2C nanotube mitigates the oxidation and aggregation of Pt nanoparticles compared with the commercial Pt/C catalyst. Thus, the Pt nanoparticles/Mo2C nanotube catalyst demonstrates improved durability. Last, the unique structural features of these Mo2C nanotube-based catalysts, which consist of nano-sized crystallites with a large active surface area, greatly facilitate the interfacial electrochemical reaction of methanol and contribute to the high catalytic activity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that Pt nanoparticles deposited onto Mo2C nanotubes via an ALD technique constitute a synergistic catalyst for use in the methanol electro-oxidation reaction. This catalyst showed much higher catalytic activity for methanol oxidation and superior CO tolerance compared with that of a conventional Pt/C catalyst. XANES and EXAFS spectroscopy and STXM analysis clearly support a strong chemical interaction between the Pt nanoparticles and Mo2C nanotubes. This design not only minimizes the required Pt usage in MOR catalysts but also enhances their CO tolerance, and thus improves their durability. These results indicate a promising strategy for the design of highly active next-generation catalysts.

References

Ganesan, R . & Lee, J. S Tungsten carbide microspheres as a noble-metal-economic electrocatalyst for methanol oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 6557–6560 (2005).

Sun, S ., Zhang, G ., Gauquelin, N ., Chen, N ., Zhou, J ., Yang, S ., Chen, W ., Meng, X ., Geng, D ., Banis, M. N ., Li, R ., Ye, S ., Knights, S ., Botton, G. A ., Sham, T . & Sun, X Single-atom catalysis using Pt/graphene achieved through atomic layer deposition. Sci. Rep. 3, 1775 (2013).

Wasmus, S . & Küver, A Methanol oxidation and direct methanol fuel cells: a selective review. J. Electroanal. Chem. 461, 14–31 (1999).

Chu, D . & Gilman, S Methanol electro-oxidation on unsupported Pt-Ru alloys at different temperatures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 1685–1690 (1996).

Metikos-Hukovic, M . & Omanovic, S Electrocatalytic oxidation of preadsorbed monolayer of CO on polycrystalline Pt60-Ru40 electrocatalyst- nucleation and growth of oxygen-containing species. J. Mol. Catal. A 136, 75–84 (1998).

Ticanelli, E ., Beery, J. G ., Paffet, M. T . & Gottesfeld, S An electrochemical, ellipsometric, and surface science investigation of the PtRu bulk alloy surface. J. Electroanal. Chem. 258, 61–77 (1989).

Metikos-Hukovic, M ., Babic, R . & Piljac, Y Kinetics and electrocatalysis of methanol oxidation on electrodeposited Pt and Pt70Ru30 catalysts. J. N. Mater. Electrochem. Syst. 7, 179–190 (2004).

Morante-Catacora, T. Y ., Ishikawa, Y . & Cabrera, C. R . Sequential electrodeposition of Mo at Pt and PtRu methanol oxidation catalyst particles on HOPG surface. J. Electroanal. Chem. 621, 103–112 (2008).

Pasupathi, S . & Tricoli, V Effect of third metal on the electrocatalytic activity of PtRu/Vulcan for methanol electro-oxidation. J. Solid State Electrochem. 12, 1093–1100 (2008).

Wang, Z. B ., Zuo, P. J . & Yin, G. P Investigation of compositions and performance of PtRuMo/C ternary catalysts for methanol electrooxidation. Fuel Cells 9, 106–113 (2009).

Kita, H ., Nakajima, H . & Shimazu, K Catalysis of the electrochemical oxidation of CH3OH by molybdenum-modified platinum. J. Electroanal. Chem. 248, 181–191 (1988).

Stalnionis, G ., Tamasauskaite-Tamasiunaite, L ., Pautieniene, V ., Sudavicius, A . & Jusys, A Modification of a Pt surface by spontaneous Sn deposition for electrocatalytic applications. J. Solid State Electrochem. 8, 892–899 (2004).

Raimodi, F ., Scherer, G. G ., Kotz, R . & Wokaun, A Nanoparticles in energy technology: examples from electrochemistry and catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 2190–2209 (2005).

Qiao, B ., Wang, A ., Yang, X ., Allard, L. F ., Jiang, Z ., Cui, Y ., Liu, J ., Li, J . & Zhang, T Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx . Nat. Chem. 3, 634–641 (2011).

Elam, J. W ., Dasgupta, N. P . & Prinz, F. B ALD for clean energy conversion, utilization and storage. MRS Bull. 36, 899–906 (2011).

Marichy, C ., Bechelany, M . & Pinna, N Atomic layer deposition of nanostructured materials for energy and environmental applications. Adv. Mater. 24, 1017–1032 (2012).

Hamalainen, J ., Ritala, M . & Leskela, M Atomic layer deposition of noble metals and their oxides. Chem. Mater. 26, 786–801 (2014).

Christensen, S. T ., Elam, J. W ., Rabuffetti, F. A ., Ma, Q ., Weigand, S. J ., Lee, B ., Seifert, S ., Stair, P. C ., Poeppelmeier, K. R ., Hersam, M. C . & Bedzyk, M. J Controlled growth of platinum nanoparticles on strontium titanate nanocubes by atomic layer deposition. Small 5, 750–757 (2009).

Zhang, X ., Tian, Z . & Shen, P. K . Composite of nanosized carbides and carbon aerogel and its supported Pd electrocatalysts for synergistic oxidation of ethylene glycol. Electrochem. Commun. 28, 9–12 (2013).

Liu, F ., Lee, J. Y . & Zhou, W. J Segmented Pt/Ru, Pt/Ni, and Pt/RuNi nanorods as model bifunctional catalysts for methanol oxidation. Small 2, 121–128 (2006).

Yan, Z ., Wang, H ., Zhang, M ., Jiang, Z ., Jiang, T . & Xie, J Pt supported on Mo2C particles with synergistic effect and strong interaction force for methanol electro-oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 95, 218–224 (2013).

Yin, M ., Li, Q ., Jensen, J. O ., Huang, Y ., Cleemann, L. N ., Bjerrum, N. J . & Xing, W Tungsten carbide promoted Pd and Pd-Co electrocatalysts for formic acid electrooxidation. J. Power Sources 219, 106–111 (2012).

He, G ., Yan, Z ., Ma, X ., Meng, H ., Shen, P. K . & Wang, C A general method for synthesizing nanoscale carbides as catalyst supports for electrocatalysis. Nanoscale 3, 3578–3582 (2011).

Nishanth, K. G ., Sridhar, P ., Pitchumani, S . & Shukla, A. K Durable transition-metal-carbide-supported Pt-Ru anodes for direct methanol fuel cells. Fuel Cells 2, 146–152 (2012).

Ma, C ., Chen, Z . & Zhao, F Synthesis of ultrafine mesoporous tungsten carbide by high-energy ball milling and its electrocatalytic activity for methanol oxidation. Chin. J. Chem. 29, 611–616 (2011).

Mellinger, Z. J ., Kelly, T. G . & Chen, J. G Pd-modified tungsten carbide for methanol electro-oxidation: from surface science studies to electrochemical evaluation. ACS Catal. 2, 751–758 (2012).

Liu, Y . & Mustain, W. E . Structural and electrochemical studies of Pt clusters supported on high-surface-area tungsten carbide for oxygen reduction. ACS Catal. 1, 212–220 (2011).

Heo, P ., Ito, K ., Tomita, A . & Hibino, T . A proton-conducting fuel cell operating with hydrocarbon fuels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 7841–7844 (2008).

Li, J ., Fu, X ., Luo, J ., Chuang, K. T . & Sanger, A. R Evaluation of molybdenum carbide as anode catalyst for proton-conducting hydrogen and ethane solid oxide fuel cells. Electrochem. Commun. 15, 81–84 (2012).

Wang, Q ., Lei, Z ., Chen, Y ., Ouyang, Q ., Gao, P ., Qi, L ., Zhu, C . & Zhang, J . Branched polyaniline/molybdenum oxide organic/inorganic heteronanostructures: synthesis and electromagnetic absorption properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 11795–11801 (2013).

Zhou, J ., Wang, J ., Fang, H ., Wu, C ., Cutler, J. N . & Sham, T. K Nanoscale chemical imaging and spectroscopy of individual RuO2 coated carbon nanotubes. Chem. Commun. 46, 2778–2780 (2010).

Zhou, J. G ., Wang, J ., Liu, H ., Banis, M. N ., Sun, X. L . & Sham, T. K Imaging nitrogen in individual carbon nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 1709–1713 (2010).

Sing, K ., Everett, D ., Haul, R ., Moscou, L ., Pierotti, R. A ., Rouquerol, J . & Siemieniewska, T Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity. Pure Appl. Chem. 57, 603–619 (1985).

Lim, B ., Jiang, M ., Camargo, P. H. C ., Cho, E. C ., Tao, J ., Lu, X ., Zhu, Y . & Xia, Y . Pd-Pt bimetallic nanodendrites with high activity for oxygen reduction. Science 324, 1302–1305 (2009).

Vellacheri, R ., Unni, S. M ., Nahire, S ., Kharul, U. K . & Kurungot, S . Pt-MoOx-carbon nanotube redox couple based electrocatalyst as a potential partner with polybenzimidazole membrane for high temperature polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell applications. Electrochim. Acta 55, 2878–2887 (2010).

Manohara, R . & Goodenough, J. B Methanol oxidation in acidic on ordered NiTi. J. Mater. Chem. 2, 875–887 (1992).

Deivaraj, T. C . & Lee, J. Y Preparation of carbon-supported PtRu nanoparticles for direct methanol fuel cell applications—a comparative study. J. Power Sources 142, 43–49 (2005).

Liu, Z ., Ling, X. Y ., Su, X . & Lee, J. Y Carbon-supported Pt and PtRu nanoparticles as catalysts for a direct methanol fuel cell. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 8234–8240 (2004).

Raghuveer, V . & Manthiram, A Mesoporous carbons with controlled porosity as an electrocatalytic support for methanol oxidation. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, A1504–A1510 (2005).

Baumer, M . & Freund, H. J Metal deposits on well-ordered oxide films. Prog. Surf. Sci. 61, 127–198 (1999).

Koningsberger, D. C . & Prints, R X-Ray Absorption: Principles, Applications, Techniques of EXAFS, SEXAFS and XANES (Wiley, New York, NY, USA, 1988).

Stöhr, J NEXAFS Spectroscopy, (Springer, Berlin, Germany, 1992).

Duchesne, P. N ., Chen, G ., Zheng, N . & Zhang, P Local structure, electronic behavior, and electrocatalytic reactivity of CO-reduced platinum-iron oxide nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 26324–26333 (2013).

Jia, Q ., Lewis, E. A ., Grice, C ., Smotkin, E. S . & Segre, C. U . In situ XAFS studies of the oxygen reduction reaction on carbon supported Pt and PtNi(1:1) catalysts. J. Phys. 190, 012157 (2009).

Chen, J. G ., Frühberger, B ., Eng, J. Jr . & Bent, B. E Controlling surface reactivities of transition metals by carbide formation. J. Mol. Catal. A 131, 285–299 (1998).

Wang, J ., Zhou, J ., Hu, Y . & Regier, T Chemical interaction and imaging of single Co3O4/graphene sheets studies by scanning transmission X-ray microscopy and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Energy Environ. Sci 6, 926–934 (2013).

Leger, J. M Mechanism aspects of methanol oxidation on platinum-based electrocatalysts. J. Appl. Electrochem. 31, 767–771 (2001).

Shropshire, J. A The catalysis of the electrochemical oxidation of formaldehyde and methanol by molybdates. J. Electrochem. Soc. 112, 465–469 (1965).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Nos. 51372271, 51172275, 51172007 and 11004229), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2012CB215402) and the start up grant from Institute of Physics (IOP). YC’s work is supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (Grant No. 51272050) and the 111 project (B13015) of Ministry Education of China to the Harbin Engineering University.

Author Contributions

CWS and YJC conceived the project and designed the work; CWS, YJC, FL and JZ designed the experiments; KZ prepared the Mo2C nanotubes samples and do the X-ray diffraction and TEM characterizations on Mo2C samples; CM and JQL performed TEM characterizations of Pt–Mo2C samples; WY and CWS carried out the ALD deposition, BET and ICP characterizations; YW and FL did electrochemical tests; JZ, JW, YH and MNB carried out measurements and data analyses of EXAFS and contributed to writing the EXAFS sections; PD and PZ performed fitting and analysis of Fourier-transformed EXAFS data; CWS prepared the manuscript, all the authors participated in analysis and discussions of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the NPG Asia Materials website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, K., Yang, W., Ma, C. et al. A highly active, stable and synergistic Pt nanoparticles/Mo2C nanotube catalyst for methanol electro-oxidation. NPG Asia Mater 7, e153 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/am.2014.122

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/am.2014.122

This article is cited by

-

Biosynthesize of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Promoter Actions in the Application of Pd/ZnO Catalyst for Electro-Oxidation of Ethanol

Catalysis Letters (2023)

-

Bimetallic Pt–Ru covalently bonded on carbon nanotubes for efficient methanol oxidation

International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials (2023)

-

Stoichiometry influence of oxide support on the catalytic efficiency of nano-palladium towards CH3OH electrooxidation

Chemical Papers (2021)

-

Blood-triggered generation of platinum nanoparticle functions as an anti-cancer agent

Nature Communications (2020)

-

Highly Efficient Electrocatalyst of Pt Electrodeposited on Modified Carbon Substrate with Ni/ZnO for Methanol Oxidation Reaction

Journal of Electronic Materials (2019)