Abstract

Background/aims

Higher case volume has been associated with improved outcomes for a number of procedures. This study was designed to investigate whether this relationship existed for trabeculectomy.

Methods

The study was retrospective and conducted at an ophthalmic unit in the UK. All patients who had unenhanced trabeculectomy between 1996 and 2000 were identified. From their notes, the surgeon who performed the trabeculectomy was ascertained as were any unplanned interventions (eg conjunctival suturing, anterior chamber reformation, repeated attendances) within the first month of surgery.

Results

Two hundred and eleven trabeculectomies were performed over the study period. Twenty nine had unplanned interventions within the first postoperative month. Analysis of the data indicated that surgeons who performed less than eight operations per year had more complications than those who performed more than 10 per annum. This difference was only significant (χ2=4.0, P=0.045) when the data were aggregated. When separated per year, although not significant, the complication rate of the lower volume group was always higher than the group performing more than 10 per year.

Conclusions

The results suggest that trabeculectomy can be added to the list of procedures in which larger case volume is associated with fewer early complications and potentially a better outcome. The findings, if replicated, tend to strengthen the argument for subspecialisation in glaucoma with its implications for training and revalidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Higher case volume has been associated with better outcomes for a number of procedures such as cancer, cardiac surgery, and colorectal surgery.1 Within ophthalmology, a relationship between volume and outcome has been suggested for cataract surgery.2, 3 This relationship between number of procedures performed and improved outcome has been found for individual practitioners and between different institutions.

As medical interventions become more numerous and more complex, many practitioners find themselves becoming increasingly sub-specialised.4 Whether this process can be halted is open to debate despite the fact that the evidence that this produces better outcomes for patients remains patchy.5, 6, 7, 8 This study was designed to look, within one institution, if the number of trabeculectomies performed per year by an individual surgeon had any bearing on the success of the operation.

Trabeculectomy remains the most commonly performed penetrating glaucoma operation.9 Although successful trabeculectomy means attaining a long-term acceptable intraocular pressure (IOP), our previous work has indicated that complications in the first month of surgery can have an adverse effect on this long-term success. This current study was designed to look purely at the ‘technical’ aspects of the operation, and analyse complications that occurred to patients under the care of each surgeon within the first postoperative month. Using this measure, we compared the number of procedures performed by surgeons per annum in our unit with the number of complications their patients sustained.

Materials and methods

This study was wholly conducted at Sunderland Eye Infirmary—a single specialty hospital with its own dedicated ophthalmic theatres and medical records. Using the hospital database and cross-checking with the operating theatre logs, all trabeculectomy operations between 1996 and 2000 were identified and the patients notes were retrieved.

To form as homogenous a group of patients as possible, certain groups were excluded:

-

Redo glaucoma surgery

-

High-risk groups for failure, for example, patients under 40 years of age, aphakic, uveitics, neovascular glaucoma, or previous conjunctival surgery.

-

Angle closure or narrow angle glaucomas

-

Previous laser trabeculoplasty.

All patients therefore had open-angle glaucoma (primary open angle, pseudoexfoliation, pigmentary). Antimetabolites were not commonly used in the institution for primary surgery during this time and the small number of these patients identified were excluded. Patients who had had small incision, corneal phacoemulsification were not excluded. All patients were operated on by consultant ophthalmologists none of whom, at that time, had a sub-specialist interest in glaucoma.

A postoperative complication was defined, for the purpose of this study, as an unplanned intervention within 1 month of the original surgery. These interventions were deviations from the normal postoperative regime of that surgeon and consisted of one or more of the following:

-

1

A conjunctival wound leak that required intervention such as padding, contact lens, resuturing, or repeated outpatient visits/in-patient stay.

-

2

An overdraining bleb with a low IOP and a shallow anterior chamber that required a prolonged stay in hospital and/or reformation or multiple extra outpatient visits.

-

3

Any other cause of a shallow anterior chamber that required intervention to reform the eye and a low IOP (ie no evidence of aqueous misdirection)

Although the definition required these interventions to occur within 1 month of surgery, in practice, the vast majority were evident within the first week postoperatively.

Results

Two hundered and eleven trabeculectomies were performed within the hospital between 1996 and 2000 that fulfilled the criteria listed above. Of these, 29 eyes had complications in the first month of a sort described above. There were no significant differences between any of the surgeons with regard to diagnosis, age of patients, previous cataract surgery, preoperative IOP, or preoperative glaucoma medications (numbers or type).

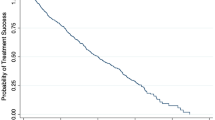

When the raw data were analysed, there was an obvious split between surgeons who performed more than 10 trabeculectomies in a year and those who performed less than 8 per year. This is summarised in Table 1 and expanded in Table 2. The results are graphically represented in Figure 1.

As has previously been described by other authors,10 the number of trabeculectomies being performed generally decreased from 1996 to 2000. When, as in Table 1, the data are separated into surgeons who performed less than 8 trabs per year and those who performed more than 10 trabs per year, the difference in proportions is 9.75%. A 95% confidence interval for the difference runs from 0.2 to 21%; χ2=4.0; P-value=0.045. The difference between the two groups is therefore significant when aggregated.

The proportions for individual years are not significantly different, but when graphically presented (Figure 1) it can be seen that there is an obvious trend of lower complications for the group who performed more than 10 operations per year.

Discussion

The relationship between higher volume and better surgical outcome has been found in a number of different procedures and a number of these have been found at the level of the individual surgeon.11 Received wisdom suggests that the more often a surgeon does a particular procedure, the better they get at doing it. This is reflected by some regulatory bodies who have set minimal numbers of procedures per annum that a surgeon should do to continue doing that procedure. This, the pressure from society for high-quality health care and the increasing number and range of interventions appear to make sub-specialism inevitable.

The results of our study suggest that for unenhanced trabeculectomy, those surgeons who performed more than 10 per annum had ‘better’ results (ie less short-term complications) than those who did less than 8 per annum. This split was only evident once the raw data were analysed, and because of the relatively small numbers, was significant when the results for all years were aggregated. When each year is separated, the results were not significant, but Figure 1 shows an obvious trend of more complications in the group who were performing fewer operations per year.

If it is accepted that the definition of complications in this study is indicative of ‘worse’ surgery, it does not of course follow that the long-term results will be worse in the more complicated group. It could be argued that short-term complications are of little importance as long as the target pressure is attained and sustained in the longer term. However, we found, in a previous study, that eyes that have complications within the first month post-trabeculectomy (without antimetabolites) were more likely to fail in the first year post-surgery than those that do not.12 We did not use long-term pressure control as an end point in this current study, as we felt these data would be too difficult to interpret in the light of different surgeons policies regarding postoperative drops, 5FU, and/or needling.

All trabeculectomies in this study were unenhanced with intraoperative 5FU or mitomycin C. This was because only a small number of surgeons used these during the study period and these were excluded in an attempt to make the comparison groups more homogenous. This latter point is strengthened by the fact that the median age and preoperative IOP were similar and only patients with open-angle glaucoma were included. This reduces bias from unequal distribution of technically more challenging cases (eg chronic narrow angle) between surgeons. All studies of volume and outcome are bedevilled by the issue of variations in case mix,13 but we feel that this is unlikely to be a major factor in our study group for the reasons given above. The exclusion of eyes that had antimetabolites also allows us to remove this as a reason for early postoperative complications.

A previous study has looked at the relationship of number of trabeculectomies performed by their outcomes. The UK National Survey of Trabeculectomy14 did not find a relationship between the number performed in the previous year and outcome of surgery. This did however contain more heterogeneous data than ours and looked at success at 1 year. Other studies have compared the results of specialist glaucoma surgeons with general ophthalmologists, but again the studies are from a group of patients with a number of other risk factors.15, 16

The results of our study must be treated with some caution as they are from a single unit. A further caution comes from the fact that the study was retrospective; however, notes retrieval was excellent (100%)—probably because of the fact that almost all the patients were still attending the hospital glaucoma clinic. Of those who did not, all had been seen within the previous 24 months; therefore, their notes had not been destroyed. The time period of the study was chosen because it was at a time when all surgeons in the unit were still performing trabeculectomy. Since 2001, most of these operations have been performed by just two surgeons who have a special interest in glaucoma (and usually use intraoperative antimetabolites)—making the study difficult to repeat in the future.

There is always a danger with this sort of study in labelling an ‘outlier’ as an incompetent surgeon. This is rarely likely to be true17 and it is interesting to note that in our results, during the study period, two surgeons crossed from being higher volume surgeons to lower volumes. When they did this, their complication rates increased. This suggests that rather than competence being the issue, the maxim that practice makes perfect (or at least better) is more apt.

In conclusion, our results indicate a generally better operative outcome (ie less likely to need corrective manoeuvres) within the first month when surgery is performed by someone who is doing 10 or more trabeculectomies per year compared to a surgeon performing less than 8 per year. This suggests that trabeculectomy can be added to the list of procedures in which a larger case volume is associated with a better outcome. If this figure is replicated in other units, regulatory bodies may wish to use the figure of greater than 10 trabeculectomies per annum as a guide for training and revalidation.

References

NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Hospital volume and healthcare outcomes, costs and patient access. Effective Healthcare Bulletin, vol 8, no 2. University of York: York, 1996.

Habib M, Mandal K, Bunce CV, Fraser SG . The relationship of volume and outcome in phacoemulsification surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2004; 88: 643–646.

Thompson JA, Snead MP, Billington B, Barrie T, Thompson JR, Sparrow JM . National audit of the outcome of primary surgery for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. II. Clinical outcomes. Eye 2002; 16: 771–777.

Lumley JS . Subspecialisation in medicine. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1993; 22 (6): 927–933.

Solomon MJ, Thomas RJ, Patellar M, Ward JE . Does type of surgeon matter in rectal cancer surgery? Evidence, guideline consensus and surgeons' views. ANZ J Surg 2001; 71 (12): 711–714.

Borenstein SH, To T, Wajja A, Langer JC . Effect of subspecialty training and volume on outcome after pediatric inguinal hernia repair. J Pediatr Surg 2005; 40 (1): 75–80.

Teenan DW, Sim KT, Hawksworth NR . Outcomes of corneal transplantation: a corneal surgeon vs the general ophthalmologist. Eye 2003; 17 (6): 727–730.

Zgibor JC, Songer TJ, Kelsey SF, Drash AL, Orchard TJ . Influence of health care providers on the development of diabetes complications: long-term follow-up from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications Study. Diabetes Care 2002; 25 (9): 1584–1590.

Jacobi PC, Dietlein TS, Krieglstein GK . Primary trabeculectomy in young adults: long-term clinical results and factors influencing the outcome. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1999; 30 (8): 637–646.

Bateman DN, Clark R, Azuara-Blanco A, Bain M, Forrest J . The impact of new drugs on management of glaucoma in Scotland: observational study. BMJ 2001; 323 (7326): 1401–1402.

Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR . Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137 (6): 511–520.

Benson SE, Mandal K, Bunce CV, Fraser SG . Is post-trabeculectomy hypotony a risk factor for subsequent failure? A case control study. BMC Ophthalmol 2005; 5 (1): 7.

Habib MS, Bunce CV, Fraser SG . The role of case mix in the relation of volume and outcome in phacoemulsification. Br J Ophthalmol 2005; 89 (9): 1143–1146.

Edmunds B, Thompson JR, Salmon JF, Wormald RP . The National Survey of Trabeculectomy. II. Variations in operative technique and outcome. Eye 2001; 15 (Part 4): 441–448.

Sung VC, Butler TK, Vernon SA . Non-enhanced trabeculectomy by non-glaucoma specialists: are results related to risk factors for failure? Eye 2001; 15 (Part 1): 45–51.

Edmunds B, Bunce CV, Thompson JR, Salmon JF, Wormald RP . Factors associated with success in first-time trabeculectomy for patients at low risk of failure with chronic open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2004; 111 (1): 97–103.

Mohammed MA . Using statistical process control to improve the quality of health care. Qual Saf Health Care 2004; 13 (4): 243–245.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, G., Hildreth, T., Phelan, P. et al. The relation of volume and outcome in trabeculectomy. Eye 21, 921–924 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702340

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702340