Abstract

Purpose To report the clinical association between macular coloboma (early-onset macular dystrophies/atrophic changes) and different phenotypes of retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

Methods Three young-adult siblings, two males and one female, were retrospectively studied. These patients underwent two complete ophthalmologic examinations (27-month follow-up), including orthoptic evaluation, colour vision test, visual field, corneal topography, electronystagmography, fluorescein angiography, and electroretinography. Eye check, automated visual field test, and complete electroretinographic study were also conducted on other asymptomatic members of the same family.

Results All symptomatic siblings were affected by manifest congenital nystagmus, poor visual acuity, and progressive visual field impairment in both eyes, bilaterally presenting macular coloboma associated with three different RP patterns: classic RP; mild dystrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, associated with subnormal electroretinographic findings (subclinical form of RP); and sector RP. The ophthalmologic reports regarding their deceased father documented that he had suffered from the same alterations of ocular movements and visual performances diagnosing, in both eyes, extensive atrophic changes of the macular area completely surrounded by pigmented bone spicules (RP-type tapeto-retinal dystrophy). The other investigated relatives did not show any specific and/or significant ocular disorder.

Conclusions In these three adult members of the same family, the concomitance between macular coloboma and different intrafamilial RP phenotypes is described. This association represents an autosomal dominant clinical entity, hitherto observed only in non familial sporadic cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macular coloboma is characterised by a sharply defined, rather large defect in the central area of the fundus that is oval or round, and coarsely pigmented. The condition is thought to result from intrauterine inflammation or to be an abnormality of development. A developmental alteration seems to be the cause thereof (i.e. of the condition) among those patients with a hereditary or family origin,1,2,3 and among those with other ocular or systemic abnormalities.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Several reports have described patients with macular coloboma associated with peripheral retinal changes such as retinitis pigmentosa (RP),4 retinal aplasia,5 Leber's congenital amaurosis,6,7 retinal dystrophy,8,9 progressive atrophy of the peripheral retina,10 or pigmented paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy.11

The purpose of this paper is to present the clinical characteristics in three adult siblings who exhibited a bilateral macular coloboma (early-onset macular dystrophies/atrophic changes), associated with different RP phenotypes. We are unaware of previous reports of nonsporadic concomitance between macular coloboma and heterogeneous intrafamilial RP patterns and could find no reference to it in a computerised search utilising Medline.

Case reports

We retrospectively analysed six members of a nonconsanguineous family coming from the South of Italy (the mother, three daughters, and two sons), who were admitted at our Clinic from September 2000 to January 2003. Only the three symptomatic patients (two sons and a daughter) underwent two complete ophthalmologic examinations (27-month follow-up), including orthoptic evaluation, colour vision test, visual field, corneal topography, electronystagmography, fluorescein angiography (FA), and electroretinography (ERG). Eye check, automated visual field test, and complete ERGs study were also conducted on the other asymptomatic members of this family (the mother and two daughters). Lens assessment was performed according to the Lens Opacities Classification System III (LOCS III).12 Computed corneal topographic studies were conducted by Optikon 2000 Keratron Corneal Analysis System (Optikon 2000 S.p.A., Roma, Italy). All ocular electrophysiological findings were achieved by Modular System BM-6000W and an Olivetti-I.B.M. personal computer (Biomedica Mangoni, Pisa, Italy). Electronystamographic waveform analyses were carried out using skin electrodes positioned at all four canthi, a ground electrode placed on the forehead, and the optokinetic stimulator type BM1620 with a semicircular bar (type BM1620-C). Full-field, scotopic, and photopic ERGs were recorded by employing Henkes corneal contact lens ERG electrodes and a ground electrode on the forehead. In each eye, the ERG tracings were obtained after maximal pupil dilatation with topical 10% phenylephrine hydrochloride, according to the ISCEV parameters.13 The results of the electrophysiological responses were compared with the normal values obtained by examining 100 normal subjects, who had been referred to our clinic for different reasons, but with no detectable eye disorder and with normal visual acuity.

The three symptomatic siblings reported a very early-onset nystagmus (in all cases firstly diagnosed during the third or fourth month of life), poor visual acuity, progressive and different visual field impairments. In each of these patients, the first available ophthalmoscopic reports, recorded when they were between 12 and 15 months old, indicated the presence of an oval dystrophic macular lesion in both the eyes. At the time of our examination, orthoptic evaluation and electronystagmography performed in each subject bilaterally showed a horizontal nystagmus, which was more evident in the elder son; the eyes oscillated with the same velocity in both directions (pendular nystagmus), assuming a jerky character in the extreme positions of gaze. In all patients, these involuntary and rhythmic conjugate oscillation of the eyes appeared as manifest congenital forms of nystagmus, typically characterised by: (i) biphasic, mostly pendular movements; (ii) increasing velocity in the slow phase; and (iii) no change on unilateral occlusion.14 The medical and drug histories of all the three siblings were unremarkable. Their familial history (Figure 1) revealed that the paternal grandfather (deceased) had suffered from early-onset nystagmus and poor visual acuity; whereas the orthoptic and ophthalmologic reports of their father (deceased) documented that he was bilaterally affected by: (i) congenital nystagmus (horizontal and pendular); (ii) both central and peripheral total blindness; (iii) absence of pupillary light reaction in pseudophakic eye treated with Nd:YAG laser capsulotomy; (iv) marked and diffuse vitreous degeneration; and (v) extensive atrophic changes and pigment clumps at the level of the macular area, associated with waxy pallor of the optic disc, very restricted retinal vessels and several mid-peripheral pigmented bone spicules (RP-type tapeto-retinal dystrophy). Several ophthalmologic findings, including best-corrected visual acuity, colour vision, intraocular pressure, anterior segment slit-lamp examination, cycloplegic ametropia, corneal topography, and electroretinography, of the three affected members are summarised in Table 1 (Cases 1–3).

Case 1

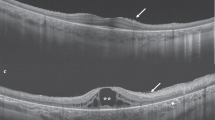

In September 2000, a 38-year-old man came under our observation for a life-long history of nystagmus, photodysphoria, and markedly reduced visual acuity, followed by nyctalopia and progressive visual field constriction. Goldmann kinetic perimetry, performed by a standardised V-4-e target, bilaterally documented the presence of a restricted remaining vision area in the inferior-nasal sector that was larger in the right eye (Figure 2a, b). Ophthalmoscopic examination bilaterally revealed posterior vitreous detachment and diffuse vitreous degeneration, several wide patches of chorioretinal geographic atrophy, associated with waxy pallor of the optic disc, attenuated retinal vessels, rare mid-peripheral bone spicules and several pigment clumps, located only in the macular atrophic area. FA revealed widespread retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) depigmentation, and detailed the atrophic features of both posterior poles (Figure 2c, d). All the ERG tracings were nonrecordable (Table 1, Case 1).

Case 1, September 2000. (a and b) Goldmann kinetic visual fields (standardised V-4-e target) bilaterally reveal a restricted remaining vision area in the inferior-nasal sector. (c and d) In both the eyes, late-phase fluorescein angiograms show several areas of chorioretinal atrophy and pigment clumps in the macular area (arrows), partially masked by the posterior vitreous degeneration. In particular, the right eye central hypofluorescence partially resembles a macular coloboma (c), suggesting that an aggravate RP concentric atrophic progression could be combined with the congenital macular colobomatous lesions.

In January 2003, during a periodical eye check, performed after a follow-up period of 27 months, the patient reported a subjective worsening of his visual performances. The biomicroscopic and ophthalmoscopic findings remained bilaterally unchanged. Otherwise, standardised V-4-e target Goldmann kinetic perimetry indicated, in each eye, a further dramatic narrowing of the vision area. These clinical findings were consistent with the diagnosis of an advanced form of classic RP associated with congenital manifest nystagmus related to severe chorioretinal atrophy of the macula.

Case 2

In September 2000, the 35-year-old sister of the patient previously described was examined. Since childhood, she had been reported to have severe central visual deficiency, associated with nystagmus and photodysphoria. During the last decade, she also noted a progressive, moderate narrowing of her visual field and slight nyctalopia. A visual field examination, performed by the Humphrey field analyser employing central 30-2 full threshold strategy and III-white stimulus, bilaterally showed an extensive mid-peripheral reduction of retinal sensitivity, with several fragmentary concentric field losses of different intensities and central ill-defined scotoma (Figure 3a, b). In each eye, ophthalmoscopy singled out diffuse and moderate vitreous degeneration, a wide macular colobomatous area of circumscribed chorioretinal atrophy and pigment clumping, associated with a temporal wedge of optic disc pallor, diffuse mid-peripheral areas of RPE dystrophy, and a pigmented perivenous clump in her right eye. FA revealed, in both eyes, a late juxtapapillary and macular staining together with weak hyperfluorescent areas of RPE depigmentation around the posterior pole (Figure 3c, d). Full-field ERG showed a conspicuous amplitude reduction with normal latency; also scotopic tracings were significantly diminished, whereas the photopic one was nonrecordable (Table 1, Case 2).

Case 2, September 2000. (a and b) Humphrey 30-2 visual fields (full threshold strategy and III-white stimulus) bilaterally show a central ill-defined scotoma, associated with irregular and diffuse mid-peripheral reduction of retinal sensitivity. The reliability of the test is low for the high number of fixation losses. (c and d) Fluorescein angiography of both eyes reveals colobomatous atrophic changes in the macular area, surrounded by the ramifications of a cilioretinal artery; weak, granular background fluorescence is visible as the result of slight mid-peripheral alteration of pigment epithelium. In the infer nasal periphery of the right eye is detectable RPE granular dystrophy (c), associated with a perivenous pigment clump (arrow). At the level of the left optic nerve head an irregular late hyperfluorescence (d) is present.

In January 2003, during a periodical eye check-up, performed after a follow-up period of 27 months, the patient reported a subjective worsening in her vision. In both eyes, even though biomicroscopic and ophthalmoscopic examinations had not revealed any significant modification, ERG studies showed a further amplitude reduction in the full-field and scotopic tracings (Table 1, Case 2). These findings documented a progressive functional alteration of peripheral photoreceptors, establishing the diagnosis of a subclinical form of RP.

Case 3

In September 2000, the 29-year-old brother of Case 1 patient was investigated. He reported early-onset poor visual acuity, related to nystagmus and photodysphoria. In the course of the last few years, the patient recognised a partial, pauci-symptomatic visual field defect and moderate nyctalopia. A visual field examination, performed by Humphrey field analyser employing central 30-2 full threshold strategy and III-white stimulus, showed a bilateral super nasal quadrantanopsia and some areas of partial scotoma in the other quadrants (Figure 4a, b). In both the eyes, fundus examination showed diffuse vitreous degeneration, large macular colobomatous atrophy, encircled by a pigment ring, in association with optic disc pallor, and mid-peripheral infer nasal bone spicules surrounded by normal retina. In both the eyes, FA documented the presence of a severe macular chorioretinal atrophy, associated with peripapillary atrophic changes and diffuse infer nasal RPE depigmentation (Figure 4c, d). Full-field and scotopic ERGs recorded a marked reduction in amplitude of all waveforms, which showed significant morphologic abnormalities, associated with normal implicit times; photopic ERG was nonrecordable (Table 1, Case 3).

Case 3, September 2000. (a and b) Humphrey 30-2 visual fields (full threshold strategy and III-white stimulus) document the presence of bilateral super nasal quadrantanopsia, with an extensive mid-peripheral decrease of the retinal sensitivity, and some partial scotomata in the other quadrants. The reliability of the test was quite good in each eye. (c and d) In both the eyes, mid-phase fluorescein angiogram shows a typical macular coloboma, associated with a sector RP pattern, revealing degenerative retinal changes in the peripapillary and infer nasal areas.

In January 2003, during a periodical eye check-up, performed after a follow-up period of 27 months, biomicroscopic and ophthalmoscopic examinations did not reveal any significant modification. Otherwise, ERG studies showed further amplitude reduction and morphologic deterioration of the full-field and scotopic tracings (Table 1, Case 3). These findings documented a progressive functional alteration of peripheral photoreceptors, indicating the diagnosis of sector RP.

These siblings exhibited a bilateral macular coloboma (early-onset macular dystrophies/atrophic changes), and three different RP patterns: (i) classic RP; (ii) diffuse, mild dystrophy of the RPE, associated with subnormal full-field and scotopic electroretinographic findings (subclinical form of RP); and (iii) sector RP. Moreover, familial history together with the retrospective analysis of their father's ophthalmologic reports are strongly suggestive of the pathologic association also in the previous generations, confirming the autosomal dominant (AD) model inheritance of the diseases.

In the literature, two case reports describing the association between macular coloboma, inherited retinal dystrophy, and keratoconus have been reported.4,5 Computed corneal mapping, performed in each eye of all our symptomatic patients to exclude the possible presence of keratoconus associated with the previously described changes of the posterior segment, has revealed normal videokeratographic patterns, characterised by a slight, symmetric astigmatism (Cases 1–3; Table 1).

Ophthalmologic examination, automated visual field test, and complete ERGs study were also conducted on other asymptomatic members of the same family (mother and two daughters), but did not show any specific and/or significant ocular disorder (Cases 4–6; Figure 1; Table 1).

Discussion

Spontaneous nystagmus occurring before about 6 months of age is called ‘congenital’ or early-onset nystagmus. Although the nystagmus rarely starts until the baby is a few months old, it is usually caused by a visual problem that is present at birth, such as albinism, aniridia, cataracts, glaucoma, coloboma, cone dysfunction, achromatopsia, high myopia, optic nerve hypoplasia, stationary night-blindness, and Leber's amaurosis.15,16,17 In each symptomatic subject described herein (Cases 1–3), the orthoptic and electronystagmographic examinations documented the presence of manifest, congenital, sensory-defect nystagmus characterised by bilateral, horizontal, biphasic, and mostly pendular-type conjugate oscillation of the eyes.14,17 Moreover, these siblings had a life-long history of rhythmic ‘wobbling’ of the eyes, photodysphoria, and poor visual acuity, all clearly indicating, together with the described clinical findings, the diagnosis of manifest congenital, sensory-defect nystagmus. In the course of their adult life, these early-onset stationary ocular disorders were being associated with progressive visual field damage, which assumed, in each patient, different objective changes corresponding to variable subjective symptoms. In fact, all these subjects had suffered from an extensive, but probably asynchronous, loss of both cone and rod functions. They bilaterally showed central colobomatous chorioretinal atrophy, responsible for the congenital nystagmus, in concomitance with three different forms of peripheral photoreceptor and RPE abnormalities. During a 27-month follow-up period, in the two younger siblings affected by these familial, RP-type tapeto-retinal dystrophies (Cases 2 and 3), we have also documented the progressive, bilateral worsening of both full-field and scotopic ERGs, confirming the ophthalmoscopic and FA diagnosis of subclinical RP (Case 2), and sector RP (Case 3).

Macular coloboma (early-onset macular dystrophies/atrophic changes) is a rare stationary inherited dysplasia of the chorioretinal tissue, which is typically associated with manifest, sensory-defect congenital nystagmus.18 All the symptomatic relatives of this macular coloboma/RP family had suffered from a colobomatous-related nystagmus, although at the time of our examination, the elder brother showed ill-defined atrophic macular changes, by now confused with the advanced RP peripheral lesions, which have already involved the entire posterior pole in both the eyes (Figure 2a, b; Case 1). Mann classified macular coloboma into three types, namely pigmented macular coloboma, nonpigmented macular coloboma, and macular coloboma associated with abnormal vessels.19 In our patients, the macular lesions seemed to be of the nonpigmented type, even if the atrophic pattern of the female subject was less expressed (Case 2), as compared to that of her brothers. On the contrary, their different peripheral abnormalities were suggestive of phenotypic intrafamilial variants of a single genotypic entity.

Manifest, sensory-defect congenital nystagmus, related to bilateral macular atrophy observed in members of the same family, can be due essentially to colobomatous macular lesions or to Leber's congenital amaurosis.18 A peculiar difference between these two congenital diseases is constituted by the presence or otherwise of the characteristic salt-and-pepper appearance in the mid-peripheral retina, which is observed only in Leber's amaurosis.18,20 This pathognomic sign is clearly absent in the siblings described herein and, particularly, in Cases 2 and 3, whose peripheral retina allows an easy diagnosis by exclusion (Figures 3c, d and 4c, d). Moreover, the genetic transmission of Leber's congenital amaurosis commonly displays an autosomal recessive (AR) model inheritance, which is not the case in this family (Figure 1); on the contrary, the heredofamilial transmission observed in our patients is typically pertinent to macular coloboma.9,18,20 In the course of the differential diagnosis, other colobomata-simulating entities, such as central areolar choroidal dystrophy, cone degenerations, inverse RP, dominant foveal dystrophy, and atrophic macular lesion in the course of RP were excluded because they are not associated with manifest, sensory-defect congenital nystagmus.14,17,18,20,21

Several cases of bilateral macular coloboma associated with different manifestations of peripheral chorioretinal inherited dystrophy have been previously reported.4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 Also, keratoconus has been described in patients with these ophthalmoscopic findings, but they were always nonfamilial cases.4,5

The male members of this Caucasian family were affected by different typical RP phenotypes,20,21 characterised by the presence of mid-peripheral bone spicules involving, respectively, the entire retina (classic RP; Case 1 and also the deceased father of the siblings) and only a retinal sector (sector RP; Case 3). Otherwise, the sister exhibited a diffuse, mid-peripheral RPE dystrophy whose familiarity, ERG findings, and FA characteristics are consistent with the diagnosis of an atypical, subclinical RP (Figure 3a, b; Table 1; Case 2).

Thus, the previously described ocular findings confirm the concomitance between macular coloboma (early-onset macular dystrophies/atrophic changes) and three different RP phenotypes. This inherited association may represent an AD clinical entity, hitherto reported only in nonfamilial sporadic cases in which the progressive tapeto-retinal dystrophy was not always a well-defined entity and, hence, heterogeneously named.4,9,10,11 On the other hand, a chance of co-occurrence cannot be ruled out. In fact, the variable RP expressivity, milder in the female than those observed in the males, without any significant clinical difference in the macular colobomatous lesions, could be similarly claimed to justify the different clinical pictures found in our patients.

In the course of the last decade, mutation analyses and several clinical evaluations have demonstrated the possibility of extensive intrafamilial and interfamilial phenotypic variations of some inherited retinal dystrophies, showing a wide range of ophthalmoscopic manifestations in the same offspring.22,23

To date, different pathogenic correlations between a specific genotypic abnormality and the development of degenerative inherited changes, involving both central and peripheral photoreceptors, have been ascertained or suspected.24 Otherwise, the concomitant occurrence of congenital and postnatal retinal diseases has been observed only in association with a few genetic polymorphisms, essentially transmitted through AR model inheritance (i.e. IMPG2, ELOVL4, CRB1, GUCY2D, and AIPL1).25,26,27 However, in the present AD-macular coloboma/RP family, these AR mutated genomic loci and/or other contiguous ones may also be indicated as possible candidate genes for the molecular genetics study, especially when considering that variations of retina-specific genes, such as RHO and NRL, are able to cause both AD-, and AR-, and sporadic-RP.24,28 Although the aetiology of the cases described herein is still unknown, the presence of bilateral macular coloboma and three different RP phenotypic variants leads us to speculate that a genomic relationship does exist between these AD disorders, which could be further investigated after an accurate chromosomal analysis of the three affected siblings.

References

Evans PJ . Familial macular colobomata. Br J Ophthalmol 1937; 21: 503–506.

Miller SA, Bresnick G . Familial bilateral macular colobomata. Br J Ophthalmol 1978; 62: 261–264.

Satorre J, Lopez JM, Martinez J, Pinera P . Dominant macular coloboma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1990; 27: 148–152.

Freedman J, Gombos GM . Bilateral macular coloboma, keratoconus, and retinitis pigmentosa. Ann Ophthalmol 1971; 3: 664–665.

Leighton DA, Harris R . Retinal aplasia in association with macular coloboma, keratoconus and cataract. Clin Genet 1973; 4: 270–274.

Margolis S, Scher BM, Carr RE . Macular colobomas in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1977; 83: 27–31.

Murayama K, Adachi-Usami E . Bilateral macular colobomas in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Doc Ophthalmol 1989; 72: 181–188.

Moore AT, Taylor DS, Harden A . Bilateral macular dysplasia (‘colobomata’) and congenital retinal dystrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 1985; 69: 691–699.

Heckenlively JR, Foxman SG, Parelhoff ES . Retinal dystrophy and macular coloboma. Doc Ophthalmol 1988; 68: 257–271.

Funada M, Okamoto I, Hayasaka S . Bilateral macular coloboma associated with progressive atrophy of the peripheral retina. Ophthalmologica 1989; 198: 8–12.

Chen MS, Yang CH, Huang JS . Bilateral macular coloboma and pigment paravenous retinochoroidal atrophy. Br J Ophthalmol 1992; 76: 250–251.

Chylack LT Jr, Wolfe JK, Singer DM, Leske MC, Bullimore MA, Bailey IL et al. The lens opacities classification system III. Arch Ophthalmol 1993; 111: 831–836.

Brigell M, Bach M, Barber C, Kawasaki K, Kooijman A . Guidelines for calibration of stimulus and recording parameters used in clinical electrophysiology of vision. Calibration Standard Committee of the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV). Doc Ophthalmol 1998; 95: 1–14.

von Noorden GK, Munoz M, Wong SY . Compensatory mechanisms in congenital nystagmus. Am J Ophthalmol 1987; 104: 387–397.

Casteels I, Harris CM, Shawkat F, Taylor D . Nystagmus in infancy. Br J Ophthalmol 1992; 76: 434–437.

Gelbart SS, Hoyt CS . Congenital nystagmus: a clinical perspective in infancy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1988; 226: 178–180.

von Noorden GK, Campos EC . Nystagmus. In: Von Noorden GK, Campos EC (eds). Binocular Vision and Ocular Motility. Theory and Management of Strabismus. Mosby Company Inc.: St Louis, MO, 2002, pp 508–533.

Jiménez-Sierra JM, Ogden TE . Abnormalities of photoreceptors. In: Jiménez-Sierra JM, Ogden TE, Van Boemel GB (eds). Inherited Retinal Diseases: A Diagnostic Guide. Mosby Company Inc.: St Louis, MO, 1989, pp 175–195.

Mann IC . On certain abnormal conditions of the macular region usually classed as colobomata. Br J Ophthalmol 1927; 11: 99–116.

Weleber RG . Retinitis pigmentosa and allied disorders. In: Ryan SJ (ed). Retina. Vol 1; Ogden TE (ed). Basic Science and Inherited Retinal Disease; Schachat AP (ed). Tumors. Mosby Company Inc.: St Louis, MO, 1994, pp 335–466.

Jiménez-Sierra JM, Ogden TE . Abnormalities of photoreceptors. In: Jiménez-Sierra JM, Ogden TE, Van Boemel GB (eds). Inherited Retinal Diseases: A Diagnostic Guide. Mosby Company Inc.: St Louis, MO, 1989, pp 111–173.

Rozet JM, Gerber S, Souied E, Ducroq D, Perrault I, Ghazi I et al. The ABCR gene: a major disease gene in macular and peripheral retinal degenerations with onset from early childhood to the elderly. Mol Genet Metab 1999; 68: 310–315.

Allikmets R . Simple and complex ABCR: genetic predisposition to retinal disease. Am J Hum Genet 2000; 67: 793–799.

Wang Q, Chen Q, Zhao K, Wang L, Wang L, Traboulsi EI . Update on the molecular genetics of retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmic Genet 2001; 22: 133–154.

Kuehn MH, Stone EM, Hageman GS . Organization of the human IMPG2 gene and its evaluation as a candidate gene in age-related macular degeneration and other retinal degenerative disorders. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001; 42: 3123–3129.

Rivolta C, Ayyagari R, Sieving PA, Berson EL, Dryja TP . Evaluation of the ELOVL4 gene in patients with autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa and Leber congenital amaurosis. Mol Vis 2003; 9: 49–51.

Khaliq S, Abid A, Hameed A, Anwar K, Mohyuddin A, Azmat Z et al. Mutation screening of Pakistani families with congenital eye disorders. Exp Eye Res 2003; 76: 343–348.

Martinez-Gimeno M, Maseras M, Baiget M, Beneito M, Antinolo G, Ayuso C et al. Mutations P51U and G122E in retinal transcription factor NRL associated with autosomal dominant and sporadic retinitis pigmentosa. Hum Mutat 2001; 17: 520.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Mr Vittorio Zoccarato, Division of Ophthalmology, Camposampiero Hospital for helping in the computer-assisted image-processing technique.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parmeggiani, F., Milan, E., Costagliola, C. et al. Macular coloboma in siblings affected by different phenotypes of retinitis pigmentosa. Eye 18, 421–428 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700689

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700689