Abstract

The preferred operation for correction of severe ptosis with minimal levator function is a brow suspension procedure. Owing to the poorly developed fascia lata in young children, and concerns about the side effects of harvesting fascia, we have, for many years, used synthetic Mersilene mesh as our suspending material. We present our experience with this material over the last 10 years. We have undertaken a retrospective analysis of the case notes of all patients undergoing brow suspension surgery, using Mersilene mesh, from 1990 to 1999. Functional and cosmetic success was recorded with respect to long-term stability. Data from 41 patients (71 lids, 30 bilateral and 11 unilateral procedures) were analysed. The minimum follow-up period was 12 months with a mean of 38.4 months (SD 23.3). We found a long-term stability of ptosis correction in 67/71 (94.4%) procedures (38/41 (92.7%) of patients). Parental satisfaction was achieved in 90.1% (64/71) of procedures or in 85.4% patients (35/41). Four lids (5.4%) of three patients (7.4%) required further surgery. Mersilene mesh is a safe and convenient suspensory material for brow suspension in young children, and provides good long-term results with a low complication rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brow suspension is considered to be the procedure of choice for surgical management of severe blepharoptosis associated with poor levator function.1,2,3 Different techniques and a variety of materials have been used.4,5,6 Most synthetic materials do not have adequate tissue incorporation and the results are typically less satisfactory in the long term.7 The synthetic macromesh material Mersilene was first reported by Downes and Collin8 in 1989, as a suspending material in ptosis surgery. It has been used as a surgical material for many years and evidence suggests that it acts as a permanent scaffold for fibrovascular ingrowth and becomes well integrated into the surrounding tissue.9,10 The mesh is inexpensive, easy to prepare and work with, and can be sterilized easily. Since fascia lata is poorly developed in young children and there are problems11,12 associated with its harvest, we have been using this material for brow suspension procedures in children undergoing ptosis surgery. We present our experience over the last 10 years (Table 1).

Methods

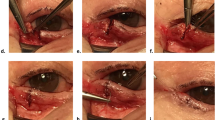

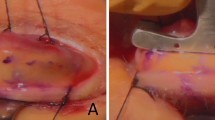

All patients undergoing brow suspension surgery using Mersilene mesh from 1990 to 1999 were identified retrospectively from operating room records, and the case notes were reviewed. All patients were operated on by the same surgeon using the same technique. Each child selected for this procedure had severe ptosis with minimal levator function. The severity of ptosis and the associated problems of compensatory head posture and occlusion of the visual axis dictated the timing of the surgery. The surgical technique was a modified Fox's brow suspension. Case notes were examined for the following information: age at the time of surgery, follow-up period, previous ptosis surgery, type of ptosis and associated systemic syndromes, and functional and cosmetic success. Functional success was based on clarity of the pupillary axis, and cosmetic success was based on our clinical impression and the satisfaction of parents. Reported complications were noted. These included failure, asymmetry, granuloma formation, and lagophthalmos.

Results

Data from 41 patients (71 lids, 30 bilateral and 11 unilateral) were analysed. All our patients were paediatric patients with a mean age of 4.4 years (SD=3.3). Most of the children (21/41, ie 51.2% of patients) required surgery before the age of 3 years. A total of 10 children were between 3 and 6 years of age and the remaining 10 children were more than 6 years, the eldest child being 13-year old. A total of 30 patients (73.2%) underwent bilateral surgery. Only 21/41 children had simple congenital ptosis. The other children had ptosis in association with some other disorder including blepharophimosis (17%), orbital fibrosis (14.6%) or associated systemic neurological finding or syndrome (17%). In all, 3/71 (4.2%) lids had undergone previous ptosis surgery.

Bilateral ptosis surgery was carried out only on children with bilateral ptosis. Although bilateral brow suspension (with levator resection in the nonptotic lid) has been recommended for unilateral ptosis with poor levator function,13 that approach has not been used in our institution.

The minimum follow-up period was 12 months with a mean of 38.4 months (SD 23.3). We found a long-term stability of ptosis correction in 67/71 (94.4%) procedures (38/41, ie 92.7% of patients). Parental satisfaction was achieved in 90.1% (64/71) of the procedures or in 85.4% patients (35/41). Four lids (5.4%) of three patients (7.4%) required further surgery. Of these, one case required reoperation after 3 years, another after 5 years, and one case with bilateral reoperations required them after 2 years.

Asymmetry between the two lids was noted in three procedures (one bilateral surgery and one unilateral procedure). Significant lagophthalmos was recorded in three lids of three patients.

Early in our use of this technique, we encountered granuloma formation. Prior to 1993, we induced granuloma formation in four eyelids of three patients (one had granuloma in both eyes). After modifying the technique, we did not encounter this problem again. The modifications include:

-

1)

routine soaking of the Mersilene mesh with antibiotic solution before implantation;

-

2)

suturing the ends of the Mersilene together, rather than tying them together, to reduce the bulk of Mersilene mesh in the wound; and

-

3)

burying the sutured Mersilene under the frontalis muscle.

Discussion

Initial results obtained with Mersilene mesh by Downes and Collin8 were very encouraging. Later, several authors reported high rates of granuloma formation and infection of the mesh.14,15 Hintschich14 reported a complication rate of 11.6% (9/76 cases) including extrusion, granuloma formation, and infection.

Mutlu et al 15 reported a rate of 6.3% for granuloma formation. Kemp and MacAndie 16 reported only a single case with extrusion of mesh because of infection. These authors otherwise found a long-term acceptable level of lid position with this material. Our study probably has the longest follow-up of such patients and shows long-term stability of ptosis correction. We had granuloma formation in three patients (four lids and five occurrences). However, since 1993, we have not had any granuloma formation.

We conclude that Mersilene mesh is a safe and convenient suspensory material for brow suspension, which provides good long-term results and has a low complication rate. Unlike other synthetic materials, the results obtained with Mersilene mesh seem to be well maintained over a mean follow-up period in excess of 3 years. In a paediatric setting, it is the material of choice as use of fascia lata is much more problematic.

References

Fox SA . Congenital ptosis. II Frontalis sling. J Paediatr Ophthalmol 1966; 3: 25–28.

Crawford JS . Repair of ptosis using frontalis muscle and fascia lata: a 20-year review. Ophthalmic Surg 1977; 8: 31–40.

Beard C . Congenital ptosis. In: Hornblass A (ed). Oculoplastic, Orbital and Reconstructive surgery, 1st ed. Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, PA, 1988, pp 119–141.

Wright WW . The use of living sutures in the treatment of ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol 1922; 51: 99–102.

Crawford JS . Fascia lata: its nature and fate after implantation and its use in ophthalmic surgery. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1968; 66: 673–745.

Goldberger S, Conn H, Lemor M . Double rhomboid silicone rod frontalis suspension. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 1991; 7: 48–53.

Wagner RS, Mauriello JA, Nelson LB, Calhoun JH, Flanagan JC, Harley RD . Treatment of congenital ptosis with frontalis suspension. A comparison of suspensory materials. Ophthalmology 1984; 91(3): 245–248.

Downes RN, Collin JRO . The Mersilene mesh sling—a new concept in ptosis surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 1989; 73: 498–501.

Adler RH, Fume CN . Use of pliable synthetic mesh in the repairs of hernias and tissue defects. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1959; 108: 199–206.

Amis AA . Filamentous implant reconstruction of tendon defects: a comparison between carbon and polyester fibre. J Bone Joint Surg 1982; 643: 682–689.

Jordan DR, Anderson RL . Obtaining fascia lata. Arch Ophthalmol 1987; 105: 1139–1140.

Wheatcroft SM, Vardy SJ, Tyers AG . Complications of fascia lata harvesting for ptosis surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 1997; 81: 581–583.

Crowell B (ed). Ptosis C.V. Mosby Company: 1969; p 100.

Hintschich CR, Zürcher M, Collin JRO . Mersilene mesh brow suspension: efficiency and complications. Br J Ophthalmol 1995; 79: 358–361.

Mutlu FM, Tuncer K, Can C . Extrusion and granuloma formation with mersilene mesh brow suspension. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1999; 30(1): 47–51.

Kemp EG, MacAndie K . Mersilene mesh as an alternative to autogenous fascia lata in brow suspension. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2001; 17(6): 419–422.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Presented as a free paper and a poster at Oxford Ophthalmological Congress, 7–10th July 2002.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sharma, T., Willshaw, H. Long-term follow-up of ptosis correction using Mersilene mesh. Eye 17, 759–761 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700498

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6700498