Abstract

Background:

Epidemiological evidence on meat intake and breast cancer is inconsistent, with little research on potentially carcinogenic meat-related exposures. We investigated meat subtypes, cooking practices, meat mutagens, iron, and subsequent breast cancer risk.

Methods:

Among 52 158 women (aged 55–74 years) in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, who completed a food frequency questionnaire, 1205 invasive breast cancer cases were identified. We estimated meat mutagen and haem iron intake with databases accounting for cooking practices. Using Cox proportional hazards regression, we calculated hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) within quintiles of intake.

Results:

Comparing the fifth to the first quintile, red meat (HR=1.23; 95% CI=1.00–1.51, P trend=0.22), the heterocyclic amine (HCA), 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (MeIQx), (HR=1.26; 95% CI=1.03–1.55; P trend=0.12), and dietary iron (HR=1.25; 95% CI=1.02–1.52; P trend=0.03) were positively associated with breast cancer. We observed elevated, though not statistically significant, risks with processed meat, the HCA 2-amino-3,4,8-trimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (DiMeIQx), mutagenic activity, iron from meat, and haem iron from meat.

Conclusion:

In this prospective study, red meat, MeIQx, and dietary iron elevated the risk of invasive breast cancer, but there was no linear trend in the association except for dietary iron.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Evidence of the role of meat intake in breast cancer is mixed. There are conflicting findings from a pooled analysis of cohort studies (Missmer et al, 2002), and a meta-analysis of cohort and case–control studies (Boyd et al, 2003), yet several recent studies indicate that meat may increase the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (Shannon et al, 2003; Steck et al, 2007; Taylor et al, 2007; Egeberg et al, 2008; Hu et al, 2008); meat-related exposures potentially involved, however, have not been well studied.

Meat mutagens, such as heterocyclic amines (HCAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are formed in meat cooked to well done at high temperatures (Sinha et al, 2005). Haem iron, found mainly in red meat, is more bioavailable than non-haem iron and, although iron homoeostasis is tightly controlled, haem iron absorption is less well regulated (Carpenter and Mahoney, 1992). Meat mutagens induce (el-Bayoumy et al, 1995; Snyderwine et al, 2002) and iron promotes (Thompson et al, 1991; Diwan et al, 1997) mammary carcinogenesis in rodent studies. Iron may also be involved in breast cancer through interaction with catechol oestrogen metabolites or production of hydroxyl radicals (Liehr and Jones, 2001; Huang, 2003; Kabat and Rohan, 2007). Limited epidemiological studies of meat mutagens (De Stefani et al, 1997; Delfino et al, 2000; Sinha et al, 2000; Steck et al, 2007; Sonestedt et al, 2008; Kabat et al, 2009; Mignone et al, 2009) and haem iron (Lee et al, 2004; Kabat et al, 2007) are inconsistent.

We used unique databases and a detailed meat questionnaire to comprehensively assess meat intake and potentially carcinogenic meat-related exposures in relation to postmenopausal invasive breast cancer in the prospective Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial.

Materials and methods

The PLCO Cancer Screening Trial is a multi-center, randomised controlled trial designed to evaluate screening methods for the early detection of prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer (Prorok et al, 2000). Briefly, 154 952 participants (78 217 women), aged 55–74 years, were recruited from 10 centres in the US between 1993 and 2001. On enrolment, the participants in the screened and non-screened arms of the trial completed a self-administered baseline questionnaire on demographics, personal/family cancer history, medical history, and lifestyle habits. Starting in 1998, diet was assessed using the Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ) (http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/DHQ/), the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) self-administered validated food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (Subar et al, 2001). Each year, participants were sent annual study update questionnaires that asked whether they had been diagnosed with cancer by a health care provider. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the NCI and PLCO study centres. All participants provided written informed consent.

Women were excluded from this analysis if they lacked the baseline questionnaire (n=2095) or the DHQ (n=16 886); missed more than seven food items on the DHG (n=1563); reported energy intake in the top or bottom 1% of women (n=1226); had a history of cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer before dietary assessment (n=6819); or no follow-up time (n=1110). After exclusions, with some subjects meeting multiple criteria, our analytic cohort consisted of 52 158 women. The vast majority of the cohort was postmenopausal based on self-reported age at last period and reason for last period. Menopausal status was ambiguous for 1.7%, but 89.1% of the women with ambiguous data were 57 or older, so the cohort was assumed to be postmenopausal.

Incident invasive breast cancer cases were identified through self-report from the annual study update questionnaire, physician reports, or through reports from the next of kin. This analysis includes only histologically confirmed invasive breast cancers based on pathology reports and medical records. Oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) data collection is ongoing; we had receptor status for 388 of our cases. Entry date for the analytic cohort was the latest of the following: randomisation, completion of baseline questionnaire, or completion of the DHQ. Follow-up ended on 31 December 2006, with breast cancer cases exiting at the date of diagnosis and non-cases exiting at the date of the most recent annual study update questionnaire without a report of breast cancer.

The DHQ assessed usual intake (frequency and portion size) of 124 food items over the past year. Nutrient intake was estimated using the Diet*Calc Analysis Program (version 1.4.3, National Cancer Institute, Applied Research Program, 2005). Red meat (g per day) included bacon, beef, cheeseburgers, cold cuts, ham, hamburgers, hot dogs, liver, pork, sausage, veal, venison, and red meat from mixed dishes. White meat included chicken, fish, and turkey. Processed meat included bacon, cold cuts, ham, hot dogs, and sausage.

With the Computerised Heterocyclic Amines Resource for Research in Epidemiology of Disease (CHARRED) (http://www.charred.cancer.gov) software application and data from a detailed meat-cooking module included in the DHQ, we generated intake estimates of three HCAs (ng per day): 2-amino-3,4,8-trimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (DiMeIQx), 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (MeIQx), and 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenyl-imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP), as well as benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), a marker of total PAH exposure, and mutagenic activity in meat (revertant colonies per day) (Sinha et al, 2005). We estimated haem iron from meat using the NCI heme iron database based on the measured values of haem iron from meat samples cooked by a range of methods to varying doneness levels (Sinha et al, 2005). The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA, 2007) Survey Nutrient Database was used to estimate iron from meat (limited to meats in the haem iron database).

Statistical analysis

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression with age at baseline as the underlying time metric; proportional hazards assumptions were not violated. Quintile cut points for the dietary exposures were based on intake in the analytic cohort, with the lowest quintile as referent. Dietary variables, except the meat mutagens, were energy adjusted using the multivariate nutrient density method; residual adjustment did not alter our findings (Willett, 1998). Tests for linear trend were based on median values of each quintile. P-values are two-sided and analyses were conducted using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Multivariate models were adjusted for the following potential confounders, which were selected because inclusion in the age-adjusted model resulted in a 10% change in risk estimates, they were associated with breast cancer in this dataset, or are established breast cancer risk factors: age, race, education, study centre, randomisation group, family history of breast cancer, age at menarche, age at menopause (natural or surgical reasons), age at first birth and number of live births, history of benign breast disease, number of mammograms during past 3 years, menopausal hormone therapy, body mass index (BMI), and intakes of alcohol, total fat, and total energy. We included cross product terms in the multivariate models to assess effect modification by alcohol intake, parity, family history of breast cancer, BMI, menopausal hormone therapy, and number of mammograms.

Results

During a mean follow-up of 5.5 years, we identified 1205 invasive breast cancer cases. Mean total meat intake was 62.9 g per 1000 kcal, with 29.5 g per 1000 kcal from red meat and 33.4 g per 1 000 kcal from white meat. Women in the highest quintile of red meat intake were slightly younger, less educated, and were less likely to have a family history of breast cancer or more than one mammogram in the past 3 years than those in the lowest quintile (Table 1). Furthermore, women consuming the most red meat were more likely to have a higher BMI, to have used oral contraceptives, to be current smokers, and to have higher energy and fat intakes. Similar patterns were seen for age, BMI, oral contraceptives, and total energy intake comparing women in the highest quintile of white meat intake to those in the lowest quintile. In contrast, high white meat consumers were more educated and less likely to be current smokers than those consuming the least white meat.

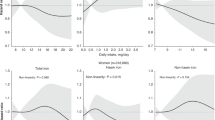

We observed statistically significant or borderline-positive associations between red meat and breast cancer starting in the second quintile, and there was no evidence for a dose–response effect (P trend=0.22), consistent with a potential threshold effect (Table 2). When we compared ER-positive/PR-positive tumours (n=259) to non-cases, the effect of red meat seemed to be stronger (Q5 vs Q1 H=1.59; 95% CI=1.03–2.48; P trend=0.09). There were no statistically significant associations with processed meat, white meat, or individual meat items.

Pan-fried meat, grilled meat, well/very well done meat, PhIP and B[a]P were not associated with breast cancer (Table 3). There was a borderline statistically significant increased risk for women consuming the most meats that were cooked well or very well done by pan-frying or grilling compared with those consuming the least. Women in the highest quintile of MeIQx compared with those in lowest had statistically significant elevated risks of breast cancer. We also observed a marginally significant increased risk of breast cancer for women with the highest intakes of DiMeIQx and mutagenic activity; both associations had a statistically significant linear trend.

Dietary iron was positively associated with breast cancer in a dose–response manner, yet there was no association for total iron or iron from supplements (Table 4). There were suggestive positive associations with iron from meat and haem iron from meat, but these relationships failed to reach statistical significance in the top quintiles.

We found some evidence of a stronger effect of red meat (P interaction=0.083), PhIP (0.014), mutagenic activity (0.010), and haem iron (0.016) on breast cancer risk in women with BMI <25 (469 cases) as opposed to those who were overweight (BMI 25–<30, 444 cases) or obese (BMI ⩾30, 292 cases) (data not shown). There was no effect modification by alcohol intake, parity, family history of breast cancer, menopausal hormone therapy, or number of mammograms.

Discussion

In this prospective study, we observed positive associations between red meat, MeIQx and dietary iron, and invasive post-menopausal breast cancer. Only the dietary iron association was statistically significant for linear trend, as the associations with red meat and MeIQx were more consistent with a threshold effect starting in the second quintile. We also found elevated, though not statistically significant, risk of breast cancer with intakes of DiMeIQx, mutagenic activity, iron from meat, and haem iron from meat.

Our results support an association between red meat and post-menopausal breast cancer, and are similar to two other recent prospective studies (Taylor et al, 2007; Egeberg et al, 2008). Our finding of a potentially stronger effect of red meat among women with ER-positive/PR-positive tumours is similar to results in pre-menopausal women for adolescent (Linos et al, 2008) and recent (Cho et al, 2006) red meat intake. However, epidemiological evidence on red meat and breast cancer is mixed, with null results in four other recent prospective studies (Holmes et al, 2003; van der Hel et al, 2004; Kabat et al, 2007, 2009). It is not clear why prospective investigations of meat and breast cancer have been inconsistent, as the potential mechanisms underlying the association should not vary in different populations. The variation could be in part due to the complexity of assessing meat intake. Our observation of a potential threshold effect is intriguing and may indicate that those consuming the least red meat are different from other women.

Similar to some (Gertig et al, 1999; Delfino et al, 2000; Kabat et al, 2009), but not all previous studies (De Stefani et al, 1997; Zheng et al, 1998; Dai et al, 2002; Steck et al, 2007), we did not observe a clear association with well/very well done and high temperature cooked meats. Our finding for MeIQx is supported by one previous case–control study (De Stefani et al, 1997); nevertheless, other studies of meat mutagens have been null (Delfino et al, 2000; Steck et al, 2007; Sonestedt et al, 2008; Kabat et al, 2009; Mignone et al, 2009). Interactions between meat (Zheng et al, 1999; Egeberg et al, 2008) or well-done meat (Zheng et al, 1999; Deitz et al, 2000) and xenobiotic-metabolising gene variants might explain these contradictory findings.

Epidemiological studies of iron and breast cancer are also mixed. Three case–control studies of dietary iron (Levi et al, 2001; Adzersen et al, 2003; Kallianpur et al, 2008) have been null, yet two others have found inverse associations (Negri et al, 1996; Cade et al, 1998). One cohort study reported positive associations for both dietary iron and haem iron among high alcohol consumers (Lee et al, 2004), yet another cohort found no association with either exposure regardless of alcohol intake (Kabat et al, 2007). Future research may need to evaluate the role of genes involved in iron absorption or oxidative stress, as breast cancer risk may differ by certain gene variants (Kallianpur et al, 2004; Hong et al, 2007).

Our results for haem iron may vary from earlier research (Lee et al, 2004; Kabat et al, 2007) that calculated haem iron as standard proportions of total iron from meat (Monsen and Balintfy, 1982; Balder et al, 2006), as we estimated haem iron based on measured values from meat samples. The pattern of risk that we observed for haem iron was similar to that for red meat. As these measures are highly correlated (r=0.77) they cannot be evaluated in the same model, making it difficult to determine whether the risk can be attributed to this individual component. However, individuals were not always ranked in the same quintile of the two exposures (weighted Kappa=0.59), indicating that haem iron may not just be a surrogate for red meat.

Strengths of this analysis include the detailed prospective data and investigation of specific meat-related exposures with separate, plausible pathways for influencing breast carcinogenesis. Although there is inherent measurement error in FFQs, this typically results in attenuation of risks. To minimise this error, our models included total energy intake. However, our ability to detect small associations may still be limited. The diet was assessed only once and this may not have been the time period most relevant to neoplasia. We also had limited ability to evaluate tumour sub-types, as our results were based on ongoing and therefore incomplete ascertainment. Finally, the observed associations could be due to unmeasured confounding, although we investigated many potential confounders.

Overall, the epidemiological evidence for meat in relation to breast cancer remains inconclusive; however, with few known modifiable risk factors, this dietary component should be further investigated. Our results regarding meat mutagens and haem iron indicate a need to evaluate multiple meat-related exposures in relation to breast carcinogenesis.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Adzersen KH, Jess P, Freivogel KW, Gerhard I, Bastert G (2003) Raw and cooked vegetables, fruits, selected micronutrients, and breast cancer risk: a case-control study in Germany. Nutr Cancer 46: 131–137

Balder HF, Vogel J, Jansen MC, Weijenberg MP, van den Brandt PA, Westenbrink S, van der Meer R, Goldbohm RA (2006) Heme and chlorophyll intake and risk of colorectal cancer in the Netherlands cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15: 717–725

Boyd NF, Stone J, Vogt KN, Connelly BS, Martin LJ, Minkin S (2003) Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature. Br J Cancer 89: 1672–1685

Cade J, Thomas E, Vail A (1998) Case–control study of breast cancer in south east England: nutritional factors. J Epidemiol Community Health 52: 105–110

Carpenter CE, Mahoney AW (1992) Contributions of heme and nonheme iron to human nutrition. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 31: 333–367

Cho E, Chen WY, Hunter DJ, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, Willett WC (2006) Red meat intake and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 166: 2253–2259

Dai Q, Shu XO, Jin F, Gao YT, Ruan ZX, Zheng W (2002) Consumption of animal foods, cooking methods, and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11: 801–808

De Stefani E, Ronco A, Mendilaharsu M, Guidobono M, Deneo-Pellegrini H (1997) Meat intake, heterocyclic amines, and risk of breast cancer: a case–control study in Uruguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 6: 573–581

Deitz AC, Zheng W, Leff MA, Gross M, Wen WQ, Doll MA, Xiao GH, Folsom AR, Hein DW (2000) N-Acetyltransferase-2 genetic polymorphism, well-done meat intake, and breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 9: 905–910

Delfino RJ, Sinha R, Smith C, West J, White E, Lin HJ, Liao SY, Gim JS, Ma HL, Butler J, Anton-Culver H (2000) Breast cancer, heterocyclic aromatic amines from meat and N-acetyltransferase 2 genotype. Carcinogenesis 21: 607–615

Diwan BA, Kasprzak KS, Anderson LM (1997) Promotion of dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-initiated mammary carcinogenesis by iron in female Sprague–Dawley rats. Carcinogenesis 18: 1757–1762

Egeberg R, Olsen A, Autrup H, Christensen J, Stripp C, Tetens I, Overvad K, Tjonneland A (2008) Meat consumption, N-acetyl transferase 1 and 2 polymorphism and risk of breast cancer in Danish postmenopausal women. Eur J Cancer Prev 17: 39–47

el-Bayoumy K, Chae YH, Upadhyaya P, Rivenson A, Kurtzke C, Reddy B, Hecht SS (1995) Comparative tumorigenicity of benzo[a]pyrene, 1-nitropyrene and 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine administered by gavage to female CD rats. Carcinogenesis 16: 431–434

Gertig DM, Hankinson SE, Hough H, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Kelsey KT, Hunter DJ (1999) N-acetyl transferase 2 genotypes, meat intake and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer 80: 13–17

Holmes MD, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Hankinson SE, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Willett WC (2003) Meat, fish and egg intake and risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 104: 221–227

Hong CC, Ambrosone CB, Ahn J, Choi JY, McCullough ML, Stevens VL, Rodriguez C, Thun MJ, Calle EE (2007) Genetic variability in iron-related oxidative stress pathways (Nrf2, NQ01, NOS3, and HO-1), iron intake, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16: 1784–1794

Hu J, La Vecchia C, Desmeules M, Negri E, Mery L, Group CC (2008) Meat and fish consumption and cancer in Canada. Nutr Cancer 60: 313–324

Huang X (2003) Iron overload and its association with cancer risk in humans: evidence for iron as a carcinogenic metal. Mutat Res 533: 153–171

Kabat GC, Cross AJ, Park Y, Schatzkin A, Hollenbeck AR, Rohan TE, Sinha R (2009) Meat intake and meat preparation in relation to risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Int J Cancer 124 (10): 2430–2435

Kabat GC, Miller AB, Jain M, Rohan TE (2007) Dietary iron and heme iron intake and risk of breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16: 1306–1308

Kabat GC, Rohan TE (2007) Does excess iron play a role in breast carcinogenesis? An unresolved hypothesis. Cancer Causes Control 18: 1047–1053

Kallianpur AR, Hall LD, Yadav M, Christman BW, Dittus RS, Haines JL, Parl FF, Summar ML (2004) Increased prevalence of the HFE C282Y hemochromatosis allele in women with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13: 205–212

Kallianpur AR, Lee SA, Gao YT, Lu W, Zheng Y, Ruan ZX, Dai Q, Gu K, Shu XO, Zheng W (2008) Dietary animal-derived iron and fat intake and breast cancer risk in the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 107: 123–132

Lee D-H, Anderson KE, Harnark LJ, Jacobs Jr DR (2004) Abstract: Dietary iron intake and breast cancer: The Iowa Women's Health Study. Available from: http://www.aacrmeetingabstracts.org/cgi/content/abstract/2004/1/535-c?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&author1==lee+dh&fulltext=iron+&andorexactfulltext=and&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&sortspec=relevance&resourcetype=HWCIT

Levi F, Pasche C, Lucchini F, La Vecchia C (2001) Dietary intake of selected micronutrients and breast-cancer risk. Int J Cancer 91: 260–263

Liehr JG, Jones JS (2001) Role of iron in estrogen-induced cancer. Curr Med Chem 8: 839–849

Linos E, Willett WC, Cho E, Colditz G, Frazier LA (2008) Red meat consumption during adolescence among premenopausal women and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 2146–2151

Mignone LI, Giovannucci E, Newcomb PA, Titus-Ernstoff L, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, Orav EJ, Willett WC, Egan KM (2009) Meat consumption, heterocyclic amines, NAT2, and the risk of breast cancer. Nutr Cancer 61: 36–46

Missmer SA, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Yaun SS, Adami HO, Beeson WL, van den Brandt PA, Fraser GE, Freudenheim JL, Goldbohm RA, Graham S, Kushi LH, Miller AB, Potter JD, Rohan TE, Speizer FE, Toniolo P, Willett WC, Wolk A, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Hunter DJ (2002) Meat and dairy food consumption and breast cancer: a pooled analysis of cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol 31: 78–85

Monsen ER, Balintfy JL (1982) Calculating dietary iron bioavailability: refinement and computerization. J Am Diet Assoc 80: 307–311

Negri E, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, D'Avanzo B, Talamini R, Parpinel M, Ferraroni M, Filiberti R, Montella M, Falcini F, Conti E, Decarli A (1996) Intake of selected micronutrients and the risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 65: 140–144

Prorok PC, Andriole GL, Bresalier RS, Buys SS, Chia D, Crawford ED, Fogel R, Gelmann EP, Gilbert F, Hasson MA, Hayes RB, Johnson CC, Mandel JS, Oberman A, O'Brien B, Oken MM, Rafla S, Reding D, Rutt W, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi L, Gohagan JK (2000) Design of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. Control Clin Trials 21: 273S–309S

Shannon J, Cook LS, Stanford JL (2003) Dietary intake and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer (United States). Cancer Causes Control 14: 19–27

Sinha R, Cross A, Curtin J, Zimmerman T, McNutt S, Risch A, Holden J (2005) Development of a food frequency questionnaire module and databases for compounds in cooked and processed meats. Mol Nutr Food Res 49: 648–655

Sinha R, Gustafson DR, Kulldorff M, Wen WQ, Cerhan JR, Zheng W (2000) 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine, a carcinogen in high-temperature-cooked meat, and breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1352–1354

Snyderwine EG, Venugopal M, Yu M (2002) Mammary gland carcinogenesis by food-derived heterocyclic amines and studies on the mechanisms of carcinogenesis of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP). Mutat Res 506–507: 145–152

Sonestedt E, Ericson U, Gullberg B, Skog K, Olsson H, Wirfalt E (2008) Do both heterocyclic amines and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids contribute to the incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women of the Malmo diet and cancer cohort? Int J Cancer 123: 1637–1643

Steck SE, Gaudet MM, Eng SM, Britton JA, Teitelbaum SL, Neugut AI, Santella RM, Gammon MD (2007) Cooked meat and risk of breast cancer--lifetime vs recent dietary intake. Epidemiology 18: 373–382

Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, McIntosh A, Rosenfeld S (2001) Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epidemiol 154: 1089–1099

Taylor EF, Burley VJ, Greenwood DC, Cade JE (2007) Meat consumption and risk of breast cancer in the UK Women's Cohort Study. Br J Cancer 96: 1139–1146

Thompson HJ, Kennedy K, Witt M, Juzefyk J (1991) Effect of dietary iron deficiency or excess on the induction of mammary carcinogenesis by 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea. Carcinogenesis 12: 111–114

US Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service (2007) USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 21. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page, http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata

van der Hel OL, Peeters PH, Hein DW, Doll MA, Grobbee DE, Ocke M, Bueno de Mesquita HB (2004) GSTM1 null genotype, red meat consumption and breast cancer risk (The Netherlands). Cancer Causes Control 15: 295–303

Willett WC (1998) Nutritional Epidemiology, 2nd edn, Oxford University Press: New York

Zheng W, Deitz AC, Campbell DR, Wen WQ, Cerhan JR, Sellers TA, Folsom AR, Hein DW (1999) N-acetyltransferase 1 genetic polymorphism, cigarette smoking, well-done meat intake, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8: 233–239

Zheng W, Gustafson DR, Sinha R, Cerhan JR, Moore D, Hong CP, Anderson KE, Kushi LH, Sellers TA, Folsom AR (1998) Well-done meat intake and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 90: 1724–1729

Acknowledgements

This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, by grant TU2 CA105666 from the National Cancer Institute, and by contracts from the Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Drs Christine Berg and Philip Prorok, the Screening Centre investigators and staff of the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial and, Information Management Services, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ferrucci, L., Cross, A., Graubard, B. et al. Intake of meat, meat mutagens, and iron and the risk of breast cancer in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Br J Cancer 101, 178–184 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605118

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605118

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Dietary Trace Element Intake and Risk of Breast Cancer: A Mini Review

Biological Trace Element Research (2022)

-

Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies

European Journal of Epidemiology (2021)

-

Iron intake, body iron status, and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis

BMC Cancer (2019)

-

Expression and replication of virus-like circular DNA in human cells

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Red meat, poultry, and fish intake and breast cancer risk among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic white women: The Breast Cancer Health Disparities Study

Cancer Causes & Control (2016)