Abstract

A total of 50 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer were enrolled in a phase II study of bevacizumab 15 mg kg−1, capecitabine 1300 mg m−2 daily for 2 weeks and gemcitabine 1000 mg m−2 weekly 2 times; cycles were repeated every 21 days. Radiological response rate was 22%; progression-free survival and over survival were 5.8 and 9.8 months respectively. Grade 3 or 4 toxicities included neutropaenia (22%), thrombocytopaenia (14%), thromboembolic events (12%), hypertension (8%) and haemorrhage (6%).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Metastatic pancreatic cancer is one of the most chemotherapy-resistant tumours. Gemcitabine is the chemotherapeutic agent of choice. However, gemcitabine results in a clinical benefit response rate (RR) of 24% and a 1-year survival of 18% only for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (Burris III et al, 1997). The addition of other cytotoxic agents to gemcitabine including capecitabine, cisplatin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin does not lead to any improvement in overall survival (OS) (Rocha Lima et al, 2004; Louvet et al, 2005; Heinemann et al, 2006; Herrmann et al, 2007). However, gemcitabine-based combinations may have value in patients with good performance status (PS). Recently, Herrmann et al (2007) reported that pancreatic cancer patients with good PS may experience improved OS and progression-free survival (PFS) with gemcitabine+capecitabine as compared with gemcitabine alone. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a potent angiogenic factor and represents a therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer (Ferrara et al, 2003). Increased VEGF expression occurs in most human tumours including pancreatic cancer (Yoshiji et al, 1996; Soh et al, 2000; Huang et al, 2001; Deryugina et al, 2002; Bremnes et al, 2006; Ozdemir et al, 2006; Black and Dinney, 2007). Bevacizumab (rhuMAb VEGF) is a recombinant humanised anti-human VEGF monoclonal antibody, which results in a synergistic anti-tumour effect in preclinical studies when combined with fluoropyrimidines or gemcitabine (Margolin et al, 2001; az-Rubio and Schmoll, 2005; Kindler et al, 2005a). The present study explored the clinical activity of gemcitabine, capecitabine and bevacizumab in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Patient eligibility

All patients provided written informed consent before study enrollment. Adult patients with previously untreated metastatic or locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS of 0 or 1, normal blood counts (leucocytes>3000 per μl, neutrophils>1500 per μl, platelets>100 000 per μl) and chemistries (bilirubin<2 mg per 100 ml, AST/ALT<5 times upper limits of normal, creatinine<1.5 mg per 100 ml) were included. Prior adjuvant therapy was permitted if completed >6 months before enrollment. Exclusion criteria included proteinuria, pregnancy, lactation, bleeding diathesis, uncontrolled hypertension or cardiovascular disease, brain metastases or recent surgery.

Treatment plan

Gemcitabine was administered in a dose of 1000 mg m−2 intravenously over 30 min on days 1 and 8; capecitabine 650 mg m−2 twice daily was administered on days 1–14 and bevacizumab 15 mg kg−1 was administered after gemcitabine on day 1 of a 21-day cycle. Treatment was continued until disease progression, death or toxicity. A maximum of 1 year of bevacizumab therapy was permitted. However, patients could receive gemcitabine and capecitabine beyond 1 year if indicated. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study.

Dose adjustments

Dose reductions for gemcitabine and capecitabine were based on manufacturer guidelines. Adverse events were graded according to National Cancer Institute, Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0 (NCI-CTC v 3.0). A cycle was not started until the absolute neutrophil count was >1500 per μl and platelet count was >100 000 per μl. Dose adjustments for gemcitabine were based on the laboratory and clinical findings on the scheduled day of administration, whereas the dose adjustment of capecitabine was based on the toxicities during the preceding cycle. There were no dose adjustments for bevacizumab in this study. Bevacizumab was held for grade 3 hypertension, grade 3 thrombosis, grade 3 haemorrhage or proteinuria ⩾2 g, until resolution. Bevacizumab was permanently discontinued for grade 4 or recurrent grade 3 vascular events. Routine use of neutrophilic growth factors was not recommended.

Study evaluations

Pretreatment included complete history and physical exam, complete blood count, chemistry including liver function tests, prothrombin time, pregnancy test for women and 12-lead electrocardiography. Urine protein/creatinine ratio was measured at baseline and every 6 weeks. History and physical exam were performed every 3 weeks. Complete blood count, serum CA 19-9 level and serum chemistries (including liver function tests) were measured on day 1 of each treatment cycle. Computed tomography scans to assess tumour size and response were obtained every 6 weeks.

The PFS was defined as the length of time during and after treatment in which the patient remained alive with cancer without disease progression. Overall survival was defined as the time from treatment initiation until demise. Responses were estimated using the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) (Therasse et al, 2000). CA 19-9 improvement by 50% was defined as a ‘CA 19-9 response’.

Statistics

The primary study aim was evaluation of PFS with the combination therapy for patients with pancreatic cancer. Secondary aims were estimation of RR, toxicity and OS. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for estimated PFS and OS curves using the Greenwood formula. The sample size was calculated to provide estimations of median PFS and median OS with reasonable accuracy. The projected 95% confidence interval width with 50 patients was approximately 3.5 months. The survival curves for OS and PFS were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. The Clopper–Pearson method was used to estimate the 95% confidence interval for the RR.

The association of survival and quantifiable variables, including age, grade and CA 19-9 level, was univariately investigated using the log-rank test.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 50 patients from three institutions were enrolled in this study between 7 September 2004 and 3 March 2007. The median follow-up duration was 8.9 months. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Treatment administration

A total of 348 cycles were administered. Median number of cycles delivered was 6 (range, 1–18). Dose modification for toxicities was required in 25 (50%) of patients. Gemcitabine dose was reduced in 20 (40%) and capecitabine in 13 (26%) patients. Reasons for treatment discontinuation are described in Table 2.

Toxicities

Haematological toxicities were common (Table 3). There were no cases of febrile neutropaenia. Grade 3 or 4 non-haematologic toxicities included two cases of diarrhoea and hand–foot syndrome secondary to capecitabine and two cases with liver function abnormalities, most likely related to biliary stent occlusion. Bevacizumab-related toxicities were hypertension, haemorrhage and thrombosis (Table 4). Most of the bleeding events were grade 1 or 2 in severity and included epistaxis (n=3) or lower gastrointestinal bleeding events (n=3). There were three cases of grade 3 haemorrhage, all of which were gastrointestinal. There was one case of grade 5 haemorrhage. This patient had cancer involvement of the gastric wall and varices. Subsequently, the study was amended: all patients with gastric involvement or varices were excluded. There were no subsequent grade 5 toxicities.

Efficacy

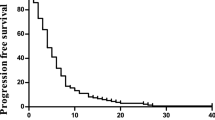

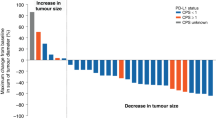

All 50 patients were included in an intention-to-treat survival and response analysis. The radiological responses were independently confirmed by the Response Review Committee. A 22% RR (PR+CR) was recorded in this trial. The median PFS was 5.8 months and the median OS was 9.8 months (Figure 1 and 2; Table 5).

A 50% decline in CA 19-9 levels was seen in a larger number of patients (65%). There was a statistically significant correlation between 50% CA 19-9 decline and PFS (P<0.0001, log-rank test), OS (P=0.0008, log-rank test) and response (P=0.0069, exact χ2-test).

Discussion

The majority of patients with pancreatic cancer have metastatic disease at diagnosis and their survival has not significantly changed over the past two decades (Baxter et al, 2007). Patients who have a poor PS derive a marginal benefit from systemic chemotherapy. The addition of bevacizumab to this combination was based on preclinical and clinical data available at the time this study was instituted (Chen, 2004; Kindler et al, 2005b). The dosage of bevacizumab used was 15 mg kg−1, which was proven as effective in combination with systemic chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer (Sandler et al, 2006). The bevacizumab-related toxicities noted in this study were manageable and similar to those reported at lower doses of this agent (Hurwitz and Saini, 2006). The study permitted administration of bevacizumab for a maximum of 12 months as there was no safety data beyond that duration. CA 19-9 decline was a useful surrogate marker for response, PFS and OS in the present study. Similar results have been reported by others (Halm et al, 2000; Ko et al, 2005). We used PFS as the primary study end point. Overall survival and RR are more commonly used. In our study, imaging studies were performed at 6-week intervals, adding to the robustness of the PFS data. In a recent meta-analysis, improved PFS and not RR correlated with an improvement in OS (Bria et al, 2007). Furthermore, OS may be confounded by second-line therapy.

The Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) randomised phase III study of gemcitabine±bevacizumab reported no survival advantage with the addition of bevacizumab (Kindler et al, 2007). Another recent, randomised phase III study of gemcitabine, erlotinib±bevacizumab for advanced pancreatic cancer did not meet its primary end point of improved survival in the bevacizumab arm (Van Cutsem et al, 2009). Based on the results of our study and the above two studies, the role of bevacizumab therapy in this disease appears to be questionable and we are not proceeding with a phase III study. This does not however reflect the role of anti-angiogenic strategies in pancreatic cancer, which are worthy of further study.

We conclude that the combination of gemcitabine, capecitabine and bevacizumab is active in pancreatic cancer. Future investigational strategies should focus on the identification of subgroups that may benefit from the addition of anti-angiogenic therapy for pancreatic cancer.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

az-Rubio E, Schmoll HJ (2005) The future development of bevacizumab in colorectal cancer. Oncology 69 (Suppl 3): 34–45

Baxter NN, Whitson BA, Tuttle TM (2007) Trends in the treatment and outcome of pancreatic cancer in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol 14: 1320–1326

Black PC, Dinney CP (2007) Bladder cancer angiogenesis and metastasis – translation from murine model to clinical trial. Cancer Metastasis Rev 26: 623–634

Bremnes RM, Camps C, Sirera R (2006) Angiogenesis in non-small cell lung cancer: the prognostic impact of neoangiogenesis and the cytokines VEGF and bFGF in tumours and blood. Lung Cancer 51: 143–158

Bria E, Milella M, Gelibter A, Cuppone F, Pino MS, Ruggeri EM, Carlini P, Nistico C, Terzoli E, Cognetti F, Giannarelli D (2007) Gemcitabine-based combinations for inoperable pancreatic cancer: have we made real progress? A meta-analysis of 20 phase 3 trials. Cancer 110: 525–533

Burris III HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD (1997) Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 15: 2403–2413

Chen HX (2004) Expanding the clinical development of bevacizumab. Oncologist 9 (Suppl 1): 27–35

Deryugina EI, Soroceanu L, Strongin AY (2002) Up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase stimulates human glioma xenograft growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 62: 580–588

Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J (2003) The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med 9: 669–676

Halm U, Schumann T, Schiefke I, Witzigmann H, Mossner J, Keim V (2000) Decrease of CA 19-9 during chemotherapy with gemcitabine predicts survival time in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 82: 1013–1016

Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, Gonnermann M, Schonekas H, Rost A, Neuhaus H, Haag C, Clemens M, Heinrich B, Vehling-Kaiser U, Fuchs M, Fleckenstein D, Gesierich W, Uthgenannt D, Einsele H, Holstege A, Hinke A, Schalhorn A, Wilkowski R (2006) Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 3946–3952

Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, Glimelius B, Bajetta E, Schuller J, Saletti P, Bauer J, Figer A, Pestalozzi B, Kohne CH, Mingrone W, Stemmer SM, Tamas K, Kornek GV, Koeberle D, Cina S, Bernhard J, Dietrich D, Scheithauer W (2007) Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 25: 2212–2217

Huang SM, Lee JC, Wu TJ, Chow NH (2001) Clinical relevance of vascular endothelial growth factor for thyroid neoplasms. World J Surg 25: 302–306

Hurwitz H, Saini S (2006) Bevacizumab in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: safety profile and management of adverse events. Semin Oncol 33: S26–S34

Kindler HL, Friberg G, Singh DA, Locker G, Nattam S, Kozloff M, Taber DA, Karrison T, Dachman A, Stadler WM, Vokes EE (2005b) Phase II trial of bevacizumab plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 8033–8040

Kindler HL, Friberg G, Singh DA, Locker G, Nattam S, Kozloff M, Taber DA, Karrison T, Dachman A, Stadler WM, Vokes EE (2005a) Phase II trial of bevacizumab plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 8033–8040

Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Oraefo E, Schrag D, Hurwitz H, McLeod HL, Mulcahy MF, Schilsky RL, Goldberg RM, Cancer and Leukemia Group (2007) A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine (G) plus bevacizumab (B) versus gemcitabine plus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced pancreatic cancer (PC): a preliminary analysis of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB). J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 25: 4508

Ko AH, Hwang J, Venook AP, Abbruzzese JL, Bergsland EK, Tempero MA (2005) Serum CA 19-9 response as a surrogate for clinical outcome in patients receiving fixed-dose rate gemcitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 93: 195–199

Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, Lledo G, Zampino MG, Andre T, Zaniboni A, Ducreux M, Aitini E, Taieb J, Faroux R, Lepere C, de GA (2005) Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 23: 3509–3516

Margolin K, Gordon MS, Holmgren E, Gaudreault J, Novotny W, Fyfe G, Adelman D, Stalter S, Breed J (2001) Phase Ib trial of intravenous recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor in combination with chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer: pharmacologic and long-term safety data. J Clin Oncol 19: 851–856

Ozdemir F, Akdogan R, Aydin F, Reis A, Kavgaci H, Gul S, Akdogan E (2006) The effects of VEGF and VEGFR-2 on survival in patients with gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 25: 83–88

Rocha Lima CM, Green MR, Rotche R, Miller Jr WH., Jeffrey GM, Cisar LA, Morganti A, Orlando N, Gruia G, Miller LL (2004) Irinotecan plus gemcitabine results in no survival advantage compared with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer despite increased tumor response rate. J Clin Oncol 22: 3776–3783

Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH (2006) Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 355: 2542–2550

Soh EY, Eigelberger MS, Kim KJ, Wong MG, Young DM, Clark OH, Duh QY (2000) Neutralizing vascular endothelial growth factor activity inhibits thyroid cancer growth in vivo. Surgery 128: 1059–1065

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van GM, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 205–216

Van Cutsem E, Vervenne WL, Bennouna J, Humblet Y, Gill S, Van Laethem JL, Verslype C, Scheithauer W, Shang A, Cosaert J, Moore MJ (2009) Phase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 27 (13): 2231–2237

Yoshiji H, Gomez DE, Shibuya M, Thorgeirsson UP (1996) Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, its receptor, and other angiogenic factors in human breast cancer. Cancer Res 56: 2013–2016

Acknowledgements

We thank Deborah Wilkinson, David Lawrence, Nancy Webb, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY. We acknowledge National Comprehensive Cancer Network and Genentech for study support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Javle, M., Yu, J., Garrett, C. et al. Bevacizumab combined with gemcitabine and capecitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase II study. Br J Cancer 100, 1842–1845 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605099

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605099

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Case Report: Long-Term Survival in Patients with Initial Lung-Only Metastasis from Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2012)