Abstract

The significance of chromosome 3p gene alterations in lung cancer is poorly understood. This study set out to investigate promoter methylation in the deleted in lung and oesophageal cancer 1 (DLEC1), MLH1 and other 3p genes in 239 non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC). DLEC1 was methylated in 38.7%, MLH1 in 35.7%, RARβ in 51.7%, RASSF1A in 32.4% and BLU in 35.3% of tumours. Any two of the gene alterations were associated with each other except RARβ. DLEC1 methylation was an independent marker of poor survival in the whole cohort (P=0.025) and in squamous cell carcinoma (P=0.041). MLH1 methylation was also prognostic, particularly in large cell cancer (P=0.006). Concordant methylation of DLEC1/MLH1 was the strongest independent indicator of poor prognosis in the whole cohort (P=0.009). However, microsatellite instability and loss of MLH1 expression was rare, suggesting that MLH1 promoter methylation does not usually lead to gene silencing in lung cancer. This is the first study describing the prognostic value of DLEC1 and MLH1 methylation in NSCLC. The concordant methylation is possibly a consequence of a long-range epigenetic effect in this region of chromosome 3p, which has recently been described in other cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Lung cancer is one of the most common causes of cancer death. The overall 5-year survival rate for surgical resection of stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can achieve 60–75% while survival rates in stage II–IV patients remain poor. Unfortunately only a small subset responds to currently available treatments. Thus, it is important to identify and characterise new molecular markers and gene targets to improve the accuracy of prognosis and develop more targeted treatment strategies to improve the clinical management of lung cancer.

Allelic loss of chromosome 3p is one of the most frequent and earliest documented events in lung cancer, with deletions at 3p24–26, 3p21.3, 3p21.1–21.2, 3p14.2 and 3p12–13, suggesting the presence of multiple tumour suppressor genes on 3p (Hung et al, 1995; Wistuba et al, 2000; Zabarovsky et al, 2002). Recent work has revealed the involvement of frequent epigenetic alterations in the inactivation of many 3p candidate genes, including BLU, FHIT, RASSF1A, RARβ and SEMA3B (Dammann et al, 2000; Virmani et al, 2000; Zochbauer-Muller et al, 2001; Zabarovsky et al, 2002; Ito et al, 2005). Detection of methylated genes in serum and sputum DNA from lung cancer patients has also raised the possibility of using DNA methylation as an early detection marker (Esteller et al, 1999; Palmisano et al, 2000; Belinsky et al, 2002; Usadel et al, 2002).

Methylation of the MLH1 gene in 3p22.3 and its correlation with a mismatch repair defect and high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) is well characterised in sporadic colorectal cancer, where this phenotype is associated with better patient survival (Sinicrope et al, 2006). In NSCLC MLH1 methylation has been described with frequencies ranging from 7 to 59% (Yanagawa et al, 2003; Safar et al, 2005) but in the absence of MSI-H (Benachenhou et al, 1998; Okuda et al, 2005). LOH within the MLH1 gene has also been detected in 55% (Benachenhou et al, 1998) and reduced MLH1 expression in 59% of lung cancers (Xinarianos et al, 2000). These intriguing findings have been followed by a recent report that MSH2, but not MLH1, methylation is a marker of poor prognosis in a Taiwanese cohort of nonsmoking female NSCLC patients (Hsu et al, 2005). It remains to be determined if a mismatch repair gene defect has a role in lung carcinogenesis and why it is not associated with typical MSI-H.

The deleted in lung and oesophageal cancer 1 (DLEC1) gene is located about 1 Mb centromeric from MLH1 (Figure 1A). The 3p21.3 region was identified as one of the common deleted regions in lung cancer. Four candidate genes in this region were analysed but no evidence of their involvement in cancer development was found (Ishikawa et al, 1997). Further analysis led to the identification of the DLC1 gene (Daigo et al, 1999), which was later renamed DLEC1. Loss of DLEC1 expression has been observed in lung, oesophageal, renal, ovarian and nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines and primary tumours and functional analyses strongly suggest that DLEC1 is a tumour suppressor gene (Daigo et al, 1999; Kwong et al, 2006, 2007). Promoter hypermethylation has been shown to be responsible for silencing of DLEC1 in ovarian cancer and in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Kwong et al, 2006, 2007) but there has been no comprehensive methylation analysis reported for lung cancer.

(A) Schematic drawing of the short arm of chromosome 3 and the relative location of the RARβ, MLH1, DLEC1, RASSF1A and BLU genes. (B) DLEC1 (NM_005106) and GAPDH expression using RT–PCR (two upper panels) and methylation status using MSP (two bottom panels) in lung cancer cell lines and in normal human lung tissue. (C) Restoration of DLEC1 expression and concomitant demethylation of the CpG island in H1299 cells using the 5-aza treatment.

In this study, we investigated if promoter hypermethylation of DLEC1 is found in lung cancer and whether it has any prognostic significance. We determined the relationship of DLEC1 methylation with patient clinicopathologic variables and other 3p molecular markers, in particular MLH1, RARβ, RASSF1 and BLU methylation.

Patients and methods

Lung cancer patients

We reviewed the NSCLC surgery database maintained by the one cardiothoracic surgeon (BMC) for the period of 1994–2000. Patients who had received induction chemotherapy or for whom sufficient tissue was not available, were excluded. The final cohort had 155 (64.9%) men and 84 women (35.1%) with a median age at diagnosis of 68 years (range, 41–87 years) and a median survival time of 36.9 months (range, 1–113 months). Data on survival was obtained from the Cancer Registry of NSW, by routine follow-up visits or contact with the patient's general practitioner. Overall survival was measured from the date of surgery to the date of death or the date of last follow-up, censored patients being those who were alive at the time of last follow-up.

This study cohort consisted of 92 (38.7%) adenocarcinomas (ADC), 54 (22.7%) large cell carcinomas (LCC), and 92 (38.7%) squamous cell carcinomas (SCC). These tumours were classified according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumour-node metastasis classification (Grondin and Liptay, 2002) and consisted of 153 (64.0%) stage I and 86 (36.0%) stage II tumours (Table 2). The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (approval no. X02-0216).

DNA extraction and bisulphite treatment

Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were reviewed by an anatomical pathologist (WAC) for tumour and matching normal tissue specimens. Six to twelve serial 4 μm sections of each block were used for DNA extraction, depending on the size of the tissue. DNA extraction was carried out using the Puregen Genomic DNA purification kit (Gentra Systems, MN, USA). Sodium bisulphite conversion was performed as previously described (Millar et al, 2002).

Expression of DLEC1 in lung cancer cell lines

Five lung cancer cell lines, A427, A549, NCI-H292, NCI-H1299 and NCI-H358, were used. Total RNA and DNA were extracted from cell pellets using RNeasy® Mini Kit and DNeasy® Tissue Kit (Qiagen GmbH Inc., Germany), respectively. Normal human adult lung RNA samples were purchased from Stratagene (Stratagene, CA, USA). One microgram of RNA from each sample was used in a reverse transcription reaction using GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Expression of DLEC1 was assessed by RT–PCR (DLEC1-F: 5′-TTCCTCCCTCGCCTACTC-3′; DLEC1-R: 5′-AAACTCATCCAGCCGCTG-3′). The primer pair was designed across exons 1 and 2 of the main DLEC1 transcript NM_005106. GAPDH was used as control.

To investigate if methylation regulates expression of DLEC1, cancer cells were treated with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor. Freshly seeded cells were grown overnight in normal medium, which was then replaced with medium containing 1 μ M of 5-aza (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, MO, USA). Cells were allowed to grow for 72 h, with 5-aza-containing medium changed every 24 h, and harvested for DNA and RNA extraction. A cell viability of >70% was retained after 72 h of treatment.

Methylation-specific PCR

Deleted in lung and oesophageal cancer 1 methylation status was assessed by a fluorescence based real-time detection quantitative methylation-specific PCR (MSP) with primers DLEC-m1, DLEC-m2 (Table 1) and a TaqMan® probe 5′-6FAM-TAATCAAACTTACGCTCACTTCGTCGCCG-BHQ1-3′ (Biosearch Technology, CA, USA) (Weisenberger et al, 2006). A reference gene MYOD1 was employed to normalise the DNA input of each sample as previously described (Eads et al, 1999; Kohonen-Corish et al, 2007). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed for DLEC1 and MYOD1 in parallel using the RealMasterMix Probe ROX (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) in the ABI7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). Deleted in lung and oesophageal cancer 1 methylation was scored as present when the value of (DLEC1/MYOD1 × 100%)⩾5 or absent if the value is <5. All samples were run in duplicate.

Methylation-specific PCR of other chromosome 3p genes RARβ, MLH1, RASSF1A and BLU was carried out (Table 1) together with MYOD1 amplification, as previously described (Eads et al, 1999; Kohonen-Corish et al, 2007). PCR steps included 30 s for denaturing, annealing and extension (40 cycles), initial denaturation and final elongation for 10 min, and annealing temperatures of 55°C (MLH1), 57°C (MYOD1), 63°C (BLU), and 58°C (RARβ, RASSF1A).

Immunohistochemistry and MSI analysis

MLH1 expression on tissue microarrays was analysed as part of a previous study (Cooper et al, 2008). Matched normal bronchial mucosa or peripheral lung parenchyma specimens were used as control tissue for each patient. MLH1 expression was scored semiquantitatively by multiplying the percentage of cells showing nuclear expression and the intensity of staining using a 3-tier grading system (1=weak, 2=moderate and 3=strong staining). Reduced MLH1 expression was taken for a score less than 100, of the maximum score of 300. MSI was analysed as previously described (Kohonen-Corish et al, 2005, 2006), except that only two markers BAT25 and BAT26 were evaluated, which are sufficient for detecting high MSI (Suraweera et al, 2002).

Statistical and survival analysis

Correlation between DLEC1 methylation and clinicopathologic parameters was determined using the χ2 test while survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier log-rank and Cox Proportional Hazards Model in the StatView package, and P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Only those variables that were significant predictors of survival outcome in univariate analysis were incorporated into multivariate analyses.

Results

High correlation between promoter methylation and loss of expression of DLEC1

Expression of DLEC1 was assessed by RT–PCR in five lung cancer cell lines. While DLEC1 was expressed in normal lung tissue, no expression was detected in the A427, A549 and H1299 lung cancer cell lines (Figure 1B). We assessed DLEC1 methylation using methylation-specific PCR (MSP). Only the methylated allele was detected in the three cell lines where DLEC1 was not expressed, while both the unmethylated and methylated alleles were detected in cell lines expressing DLEC1 (Figure 1B). Methylation was rare in normal lung tissue (2.5%, 200 specimens analysed). To determine whether methylation directly regulates the silencing of DLEC1, the cell line H1299 was treated with 5-aza, a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor. After 3 days of 5-aza treatment, DLEC1 expression was restored and demethylation observed (Figure 1C).

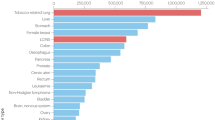

Promoter methylation of DLEC1, MLH1, RARβ, RASSF1A and BLU in lung cancer

We employed MSP to assess the promoter methylation status of the five 3p candidate genes in 239 NSCLCs. Methylation was detected in 123 patients (51.5%) for RARβ, 86 (36.0%) for MLH1, 93 (38.9%) for DLEC1, 78 (32.6%) for RASSF1A and 85 (35.6%) for BLU (Table 2). Next we investigated the relationship between methylation of each set of two out of five genes. Significant correlation was observed between DLEC1 and MLH1 (P=0.0002), DLEC1 and RASSF1A (P=0.0003), and RASSF1A and BLU methylation (P=0.017). MLH1 methylation was also associated with RASSF1A (P=0.0006) and BLU (P=0.0005) (Table 3). Methylation of at least one of the five genes was detected in 204 of 239 (85.4%) patients; methylation of at least two genes in 139 (58.2%); three genes in 77 (32.2%); four genes in 36 (15.1%); and methylation of all five genes was detected in only nine (3.8%) patients.

MLH1 expression in lung cancer tissue and MSI

Expression of MLH1 was previously determined using immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays in 105 of the 239 patients (Cooper et al, 2008). MSI was analysed in the whole cohort of 239 patients. Reduced MLH1 expression was detected in seven of the 105 cancers including an apparent loss of MLH1 expression in two cancers, but none of the matching DNA specimens prepared from a larger area of the tumour showed any MSI using markers BAT25 and BAT26. Also, none of the seven cancers with reduced MLH1 expression showed MLH1 promoter methylation. In the rest of the cohort MSI-H was detected in a stage 1B ADC (one marker) and a stage 2A LCC (both markers), of which only the latter was methylated in MLH1. There was no significant correlation between reduced MLH1 expression and survival (P=0.421).

Methylation of DLEC1 and MLH1 are associated with poor patient survival

A statistically significant association between methylation and histologic type was observed, where MLH1 methylation had a higher frequency in SCC (45.6%) and LCC (40.7%) compared with ADC (22.8%); RASSF1A methylation was associated with LCC (53.7%); BLU and RARβ methylation with ADC (45.7% and 60.9%). Furthermore, MLH1 and DLEC1 methylation were associated with the presence of regional lymph-node metastases and AJCC stage II. No association was observed between methylation of the five genes and age of diagnosis, gender or tumour differentiation status, except that BLU methylation was more common in older patients (Table 2).

Methylation of DLEC1 (P=0.0005), MLH1, (P=0.004), and RASSF1A (P=0.024) as well as regional lymph node status (P<0.0001) and AJCC stage (P<0.0001) were associated with poorer overall survival (Figure 2 and Table 2). RARβ and BLU methylation were not prognostic in the whole NSCLC cohort using the Kaplan–Meier log-rank analysis (P=0.313 and 0.474). Regional lymph node metastases and AJCC stage are two of the known prognostic factors for NSCLC and these two parameters are dependent predictors of survival in our cohort. Therefore, a bivariate analysis with the molecular marker predictor (DLEC1, MLH1 or RASSF1A methylation) and AJCC stage was set up. Methylation of either DLEC1 or MLH1 but not RASSF1A was a prognostic indicator independent of AJCC stage in the entire patient cohort (Table 4). Deleted in lung and oesophageal cancer 1 methylation was also a prognostic factor independent of AJCC stage in the SCC subgroup of patients (HR, 1.754; 95% CI, 1.023–3.007; P=0.041) and MLH1 methylation in LCC (HR, 2.926; 95% CI, 1.358–6.308; P=0.006).

We then investigated if concordant methylation of two genes affect patient prognosis (Figure 2; Table 4). Concordant MLH1/DLEC1 methylation was associated with poorer overall survival in both univariate (HR, 2.075; 95% CI, 1.428–3.015; P=0.0001) and bivariate (HR, 1.668; 95% CI, 1.138–2.447; P=0.009) analyses. Also, MLH1 methylation was prognostic in combination with RASSF1A methylation independent of AJCC stage in all patients (HR, 1.688, 95% CI, 1.127–2.529; P=0.011) and particularly in the LCC cohort (HR, 3.223; 95% CI, 1.482–7.008; P=0.003).

Discussion

Deleted in lung and oesophageal cancer 1 is a candidate tumour suppressor gene in multiple cancers. Although the function of DLEC1 is unclear, it suppresses tumour growth or reduces invasiveness of cancer cells (Daigo et al, 1999; Kwong et al, 2006, 2007). In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that the DLEC1 promoter is methylated in lung cancer. The demethylating agent 5-aza reversed loss of mRNA expression in lung cancer cell lines. Frequent DLEC1 methylation (34.2%) was observed in NSCLC and was most common in SCC (47.8%). DLEC1 methylation was cancer-specific, as it was only rarely detected in matching normal lung tissue, and was strongly associated with stage II tumours and the spread of cancer to regional lymph nodes (P<0.0001). DLEC1 methylation was also associated with shorter overall survival in the whole cohort and in the SCC group of patients, and this remained statistically significant upon bivariate analysis with AJCC stage (Table 4). As there is no antibody available for DLEC1, we could not determine what proportion of methylated tumours would show loss or reduced DLEC1 protein expression. However, it has been previously demonstrated that DLEC1 RNA expression was lost in eight of 30 primary lung cancers and that this was not due to gene mutations (Daigo et al, 1999).

The MLH1 gene is located within 1 Mb of DLEC1 in a locus that shows 55% LOH in NSCLC (Benachenhou et al, 1998). Therefore, there has been some interest in determining the biological significance of reduced MLH1 gene expression and promoter methylation in lung cancer. As gene alterations can cause either increased sensitivity or resistance of tumours to chemotherapy treatment, we excluded those patients who had received induction chemotherapy prior to surgery to avoid a possible bias in the molecular analyses. MLH1 methylation was found in 36% of the cancers but did not result in the loss of gene expression in the 105 cancers analysed with immunohistochemistry. Only 6.7% of the cancers showed reduced MLH1 expression with stringent criteria (<100 of the maximum score of 300) and none of these specimens were methylated. We also found that MLH1 methylation was patchy and/or monoallelic in region C of the MLH1 promoter by using combined bisulphite-restriction analysis (COBRA, Hitchins et al, 2007) (data not shown). This is consistent with the finding that MSI is extremely rare in NSCLC.

It is intriguing therefore, that MLH1 methylation showed strong prognostic significance, which is reported here for the first time. It was a marker of poor survival in the whole cohort, and particularly in the LCC subgroup, with both univariate and bivariate analyses. This is in contrast to colorectal adenocarcinoma where MLH1 methylation causes the MSI-H phenotype, which has improved prognosis. There was a high correlation between DLEC1 and MLH1 methylation (P=0.0002). As for DLEC1, MLH1 methylation was associated with stage II tumours and spread to regional lymph nodes. Concordant methylation of MLH1 and DLEC1 was also a marker of poor prognosis independent of stage in the whole cohort (Table 4).

The close correlation between MLH1 and DLEC1 methylation may be a consequence or a byproduct of a long-range epigenetic effect in this region of chromosome 3p. The first such chromosomal region reported was 2q14.2, which shows modification of chromatin structure such as histone H3-K9 methylation in colon cancer cells. This results in clusters of both methylated and unmethylated genes being coordinately suppressed (Frigola et al, 2006). It has recently been shown that DLEC1 and MLH1 are also subject to long-range epigenetic regulation in colon cancer (Hitchins et al, 2007). Multiple genes in this region can be simultaneously silenced through promoter hypermethylation and histone methylation in MSI-positive colorectal cancers. This effect appears to extend centromeric from the MLH1 gene and does not always reach DLEC1 in all specimens. In bladder cancer there is also evidence of such long-range epigenetic regulation around the DLEC1 gene, but here the predominant mechanism is gene silencing through histone methylation rather than CpG methylation, and MLH1 was not analysed (Stransky et al, 2006). The two genes, which were analysed in both studies, DLEC1 and its neighbour PLCD1, are silenced through DNA methylation and H3-K9 dimethylation in colorectal cancer whereas in bladder cancer they are silenced through histone H3-K9 trimethylation. This suggests that there are tissue-specific differences in this regulation. Therefore, if such long-range epigenetic regulation of chromosome 3p is also operating in lung cancer, it is possible that some genes in the region may be affected less than others. As a consequence the overall methylation in this region could serve as a marker of poorer prognosis but only some genes show complete loss of function.

The other three genes analysed in this study RASSF1A, BLU and RARβ are known to be methylated in lung cancer and all have shown functional characteristics of tumour suppressor genes (Toulouse et al, 2000; Shivakumar et al, 2002; Agathanggelou et al, 2003). RARβ is located 12 Mb telomeric from MLH1, and RASSF1A and BLU about 12 Mb centromeric from DLEC1. RASSF1 methylation was also highly correlated with DLEC1 (P=0.0003) and MLH1 methylation (P=0.0006), whereas RARβ was methylated independent of the other genes. The correlation between RASSF1A and BLU methylation observed here (P=0.017) has also been described previously (Agathanggelou et al, 2003). However, none of these three markers were as strongly prognostic as DLEC1 and MLH1 methylation in this cohort. In a previous study RASSF1A methylation correlated with poor survival (Tomizawa et al, 2002), but this has not been confirmed in all cohorts (Toyooka et al, 2004; Choi et al, 2005). Here, RASSF1A methylation was a prognostic marker in univariate analyses but not independent of stage, as was also observed previously (Choi et al, 2005). It was interesting that concordant methylation of MLH1 with RASSF1 was an independent marker of poor prognosis. This suggests that a possible long-range epigenetic effect may extend centromeric from the DLEC1 locus but not telomeric from the MLH1 locus.

Taken together, our study has described two new prognostic markers, methylation of DLEC1 and MLH1 on chromosome 3p. Methylation of these two genes is clearly associated with each other and with methylation of RASSF1 and BLU, which are ∼12 Mb centromeric from DLEC1. MLH1 methylation itself does not lead to gene silencing in lung cancer and the biological significance of DLEC1 methylation also needs further study. In any case, concordant methylation of MLH1 with DLEC1 or RASSF1A is a valuable prognostic indicator in lung cancer. Future studies should reveal whether DLEC1, another gene or perhaps multiple genes in this region are functionally the most important in lung carcinogenesis.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Agathanggelou A, Dallol A, Zochbauer-Muller S, Morrissey C, Honorio S, Hesson L, Martinsson T, Fong KM, Kuo MJ, Yuen PW, Maher ER, Minna JD, Latif F (2003) Epigenetic inactivation of the candidate 3p21.3 suppressor gene BLU in human cancers. Oncogene 22: 1580–1588

Belinsky SA, Palmisano WA, Gilliland FD, Crooks LA, Divine KK, Winters SA, Grimes MJ, Harms HJ, Tellez CS, Smith TM, Moots PP, Lechner JF, Stidley CA, Crowell RE (2002) Aberrant promoter methylation in bronchial epithelium and sputum from current and former smokers. Cancer Res 62: 2370–2377

Benachenhou N, Guiral S, Gorska-Flipot I, Labuda D, Sinnett D (1998) High resolution deletion mapping reveals frequent allelic losses at the DNA mismatch repair loci hMLH1 and hMSH3 in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 77: 173–180

Choi N, Son DS, Song I, Lee HS, Lim YS, Song MS, Lim DS, Lee J, Kim H, Kim J (2005) RASSF1A is not appropriate as an early detection marker or a prognostic marker for non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer 115: 575–581

Cooper WA, Kohonen-Corish MRJ, Chan C, Kwun SY, McCaughan B, Kennedy C, Sutherland RL, Lee C-S (2008) Prognostic significance of DNA repair proteins MLH1, MSH2 and MGMT expression in non-small cell lung cancer and precursor lesions. Histopathology 52: 613–622

Daigo Y, Nishiwaki T, Kawasoe T, Tamari M, Tsuchiya E, Nakamura Y (1999) Molecular cloning of a candidate tumor suppressor gene, DLC1, from chromosome 3p21.3. Cancer Res 59: 1966–1972

Dammann R, Li C, Yoon JH, Chin PL, Bates S, Pfeifer GP (2000) Epigenetic inactivation of a RAS association domain family protein from the lung tumour suppressor locus 3p21.3. Nature Genet 25: 315–319

Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Danenberg PV, Laird PW (1999) CpG island hypermethylation in human colorectal tumors is not associated with DNA methyltransferase overexpression. Cancer Res 59: 2302–2306

Esteller M, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Rosell R, Sidransky D, Baylin SB, Herman JG (1999) Detection of aberrant promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes in serum DNA from non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Res 59: 67–70

Frigola J, Song J, Stirzaker C, Hinshelwood RA, Peinado MA, Clark SJ (2006) Epigenetic remodeling in colorectal cancer results in coordinate gene suppression across an entire chromosome band. Nature Genet 38: 540–549

Grondin SC, Liptay MJ (2002) Current concepts in the staging of non-small cell lung cancer. Surg Oncol 11: 181–190

Hitchins MP, Lin VA, Buckle A, Cheong K, Halani N, Ku S, Kwok CT, Packham D, Suter CM, Meagher A, Stirzaker C, Clark S, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL (2007) Epigenetic inactivation of a cluster of genes flanking MLH1 in microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 67: 9107–9116

Hsu HS, Wen CK, Tang YA, Lin RK, Li WY, Hsu WH, Wang YC (2005) Promoter hypermethylation is the predominant mechanism in hMLH1 and hMSH2 deregulation and is a poor prognostic factor in nonsmoking lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11: 5410–5416

Hung J, Kishimoto Y, Sugio K, Virmani A, McIntire DD, Minna JD, Gazdar AF (1995) Allele-specific chromosome 3p deletions occur at an early stage in the pathogenesis of lung carcinoma. JAMA 273: 558–563

Ishikawa S, Kai M, Tamari M, Takei Y, Takeuchi K, Bandou H, Yamane Y, Ogawa M, Nakamura Y (1997) Sequence analysis of a 685-kb genomic region on chromosome 3p22–p21.3 that is homozygously deleted in a lung carcinoma cell line. DNA Res 4: 35–43

Ito M, Ito G, Kondo M, Uchiyama M, Fukui T, Mori S, Yoshioka H, Ueda Y, Shimokata K, Sekido Y (2005) Frequent inactivation of RASSF1A, BLU, and SEMA3B on 3p21.3 by promoter hypermethylation and allele loss in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 225: 131–139

Kohonen-Corish MR, Cooper WA, Saab J, Thompson JF, Trent RJ, Millward MJ (2006) Promoter hypermethylation of the O(6)-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase gene and microsatellite instability in metastatic melanoma. J Inv Dermatol 126: 167–171

Kohonen-Corish MR, Daniel JJ, Chan C, Lin BP, Kwun SY, Dent OF, Dhillon VS, Trent RJ, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL (2005) Low microsatellite instability is associated with poor prognosis in stage C colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 23: 2318–2324

Kohonen-Corish MR, Sigglekow ND, Susanto J, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL, Dent OF, Chan C, Lin BP, Seng TJ, Laird PW, Young J, Leggett BA, Jass JR, Sutherland RL (2007) Promoter methylation of the mutated in colorectal cancer gene is a frequent early event in colorectal cancer. Oncogene 26: 4435–4441

Kwong J, Chow LS, Wong AY, Hung WK, Chung GT, To KF, Chan FL, Daigo Y, Nakamura Y, Huang DP, Lo KW (2007) Epigenetic inactivation of the deleted in lung and esophageal cancer 1 gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Genes Chrom Cancer 46: 171–180

Kwong J, Lee JY, Wong KK, Zhou X, Wong DT, Lo KW, Welch WR, Berkowitz RS, Mok SC (2006) Candidate tumor-suppressor gene DLEC1 is frequently downregulated by promoter hypermethylation and histone hypoacetylation in human epithelial ovarian cancer. Neoplasia 8: 268–278

Millar DS, Warnecke PM, Melki JR, Clark SJ (2002) Methylation sequencing from limiting DNA: embryonic, fixed, and microdissected cells. Methods 27: 108–113

Okuda T, Kawakami K, Ishiguro K, Oda M, Omura K, Watanabe G (2005) The profile of hMLH1 methylation and microsatellite instability in colorectal and non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Med 15: 85–90

Palmisano WA, Divine KK, Saccomanno G, Gilliland FD, Baylin SB, Herman JG, Belinsky SA (2000) Predicting lung cancer by detecting aberrant promoter methylation in sputum. Cancer Res 60: 5954–5958

Safar AM, Spencer III H, Su X, Coffey M, Cooney CA, Ratnasinghe LD, Hutchins LF, Fan CY (2005) Methylation profiling of archived non-small cell lung cancer: a promising prognostic system. Clin Cancer Res 11: 4400–4405

Shivakumar L, Minna J, Sakamaki T, Pestell R, White MA (2002) The RASSF1A tumor suppressor blocks cell cycle progression and inhibits cyclin D1 accumulation. Mol Cell Biol 22: 4309–4318

Sinicrope FA, Rego RL, Halling KC, Foster N, Sargent DJ, La Plant B, French AJ, Laurie JA, Goldberg RM, Thibodeau SN, Witzig TE (2006) Prognostic impact of microsatellite instability and DNA ploidy in human colon carcinoma patients. Gastroenterology 131: 729–737

Stransky N, Vallot C, Reyal F, Bernard-Pierrot I, de Medina SG, Segraves R, de Rycke Y, Elvin P, Cassidy A, Spraggon C, Graham A, Southgate J, Asselain B, Allory Y, Abbou CC, Albertson DG, Thiery JP, Chopin DK, Pinkel D, Radvanyi F (2006) Regional copy number-independent deregulation of transcription in cancer. Nature Genet 38: 1386–1396

Suraweera N, Duval A, Reperant M, Vaury C, Furlan D, Leroy K, Seruca R, Iacopetta B, Hamelin R (2002) Evaluation of tumor microsatellite instability using five quasimonomorphic mononucleotide repeats and pentaplex PCR. Gastroenterology 123: 1804–1811

Tomizawa Y, Kohno T, Kondo H, Otsuka A, Nishioka M, Niki T, Yamada T, Maeshima A, Yoshimura K, Saito R, Minna JD, Yokota J (2002) Clinicopathological significance of epigenetic inactivation of RASSF1A at 3p21.3 in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 8: 2362–2368

Toulouse A, Morin J, Dion PA, Houle B, Bradley WE (2000) RARbeta2 specificity in mediating RA inhibition of growth of lung cancer-derived cells. Lung Cancer 28: 127–137

Toyooka S, Suzuki M, Maruyama R, Toyooka KO, Tsukuda K, Fukuyama Y, Iizasa T, Aoe M, Date H, Fujisawa T, Shimizu N, Gazdar AF (2004) The relationship between aberrant methylation and survival in non-small cell lung cancers. Br J Cancer 91: 771–774

Usadel H, Brabender J, Danenberg KD, Jeronimo C, Harden S, Engles J, Danenberg PV, Yang S, Sidransky D (2002) Quantitative adenomatous polyposis coli promoter methylation analysis in tumor tissue, serum, and plasma DNA of patients with lung cancer. Cancer Res 62: 371–375

Virmani AK, Rathi A, Zochbauer-Muller S, Sacchi N, Fukuyama Y, Bryant D, Maitra A, Heda S, Fong KM, Thunnissen F, Minna JD, Gazdar AF (2000) Promoter methylation and silencing of the retinoic acid receptor-beta gene in lung carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1303–1307

Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, Faasse MA, Kang GH, Widschwendter M, Weener D, Buchanan D, Koh H, Simms L, Barker M, Leggett B, Levine J, Kim M, French AJ, Thibodeau SN, Jass J, Haile R, Laird PW (2006) CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nature Genet 38: 787–793

Wistuba II, Behrens C, Virmani AK, Mele G, Milchgrub S, Girard L, Fondon III JW, Garner HR, McKay B, Latif F, Lerman MI, Lam S, Gazdar AF, Minna JD (2000) High resolution chromosome 3p allelotyping of human lung cancer and preneoplastic/preinvasive bronchial epithelium reveals multiple, discontinuous sites of 3p allele loss and three regions of frequent breakpoints. Cancer Res 60: 1949–1960

Xinarianos G, Liloglou T, Prime W, Maloney P, Callaghan J, Fielding P, Gosney JR, Field JK (2000) hMLH1 and hMSH2 expression correlates with allelic imbalance on chromosome 3p in non-small cell lung carcinomas. Cancer Res 60: 4216–4221

Yanagawa N, Tamura G, Oizumi H, Takahashi N, Shimazaki Y, Motoyama T (2003) Promoter hypermethylation of tumor suppressor and tumor-related genes in non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Sci 94: 589–592

Zabarovsky ER, Lerman MI, Minna JD (2002) Tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 3p involved in the pathogenesis of lung and other cancers. Oncogene 21: 6915–6935

Zochbauer-Muller S, Fong KM, Maitra A, Lam S, Geradts J, Ashfaq R, Virmani AK, Milchgrub S, Gazdar AF, Minna JD (2001) 5′ CpG island methylation of the FHIT gene is correlated with loss of gene expression in lung and breast cancer. Cancer Res 61: 3581–3585

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Cancer Institute NSW for funding, and the Australian Cancer Research Foundation for their sponsorship of the ACRF Unit for the Molecular Genetics of Cancer at the Garvan Institute. MKC is a Cancer Institute NSW Career Development Fellow and RLS an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Seng, T., Currey, N., Cooper, W. et al. DLEC1 and MLH1 promoter methylation are associated with poor prognosis in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer 99, 375–382 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604452

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604452

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

DNA methylation patterns suggest the involvement of DNMT3B and TET1 in osteosarcoma development

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2023)

-

Dynamics of genome architecture and chromatin function during human B cell differentiation and neoplastic transformation

Nature Communications (2021)

-

PM2.5 exposure and DLEC1 promoter methylation in Taiwan Biobank participants

Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine (2020)

-

Intravenous 5-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine administered with tetrahydrouridine increases the proportion of p16-expressing circulating tumor cells in patients with advanced solid tumors

Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology (2020)

-

The pro-survival function of DLEC1 and its protection of cancer cells against 5-FU-induced apoptosis through up-regulation of BCL-XL

Cytotechnology (2019)