Abstract

Data sources

The review searched for published and ongoing trials in several databases with no restrictions on language or date of publication which included the Cochrane Oral Health Group Trials, Central Register of Controlled Trials, Medline, CINAHL, Embase, WHO Clinical Trials Registry Platform and clinical trial.gov.

Study selection

Randomised clinical trials were considered that evaluated any intervention compared with another or with placebo for treating postoperative bleeding (PEB), post extraction. The primary outcome measures sought were: bleeding, amount of blood loss and cessation time required to control bleeding. The secondary outcomes: patient reported outcomes, such as pain or discomfort and adverse events.

Data extraction and synthesis

Three pairs of review authors independently screened the records.

Results

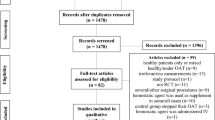

The search strategy identified 1526 articles and abstracts. After removal of duplicates, 943 records were screened. Thirty-four full texts were examined. No trials met the inclusion criteria for the review.

Conclusions

We were unable to identify any reports of randomised controlled trials that evaluated the effects of different interventions for the treatment of post-extraction bleeding. In view of the lack of reliable evidence on this topic, clinicians must use their clinical experience to determine the most appropriate means of treating this condition, depending on patient-related factors. There is a need for well designed and appropriately conducted clinical trials on this topic, which conform to the CONSORT statement (www.consort-statement.org/).

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Individuals with haematological disorders, who are suffering side effects of chemotherapeutic agents or who are taking anticoagulants are frequently at risk of bleeding. Performing surgical dental procedures increases the risk, however, sometimes postoperative bleeding may be due to the type of intervention, surgical expertise or vascularisation of the area of the surgery.1

The prevention and management of possible intraoperative and postoperative bleeding from surgical dental procedures requires an important understanding that every practitioner should be up to date with regards to the materials and techniques available to avoid the unwanted side effect as much as possible.

The Cochrane review selected the topic to assess the effects of various interventions for the treatment of different types of postoperative bleeding (PEB) in cases where no preventive measures were used.

Only randomised clinical trials were accepted for inclusion. However after an intensive search, no articles were included in the review.

Despite the efforts of good methodological review, no research articles seem available on the topic of management of postoperative bleeding.

The authors considered different definitions of PEB as described in the literature, as postoperative bleeding is recognised as bleeding that continues for more than 12 hours after the surgical procedure and results in patients needing to return to the dental practitioner or visit the emergency room, maybe need blood transfusions and has clinical evidence of haematomas and ecchymosis.2

The authors recommend the implication of research to perform randomised clinical trials to evaluate the effects of interventions for the treatment of PEB.

It seems that the best treatment for an unwanted side effect is prevention before, during and immediately after the dental surgery.3,4,5

Most of the available articles emphasise prevention, which in reality is the key point in managing patients with possible risk of postoperative bleeding.

It is also true that postoperative bleeding may be associated with physical trauma and clot removal. In some cases it is the failure of the patient to correctly follow the postoperative instructions. Intraoral tissues are highly vascularised and in some cases the bleeding may not be due to a systemic condition or a side effect of a medication. It may be due to a more vascularised, inflamed granulation tissue.

Sutures are known to be a good aid, bringing together the tissues, and haemostatic agents are available to control the immediate postoperative bleeding but alone may not be helpful. Other haemostatic agents exist, such as resorbable dressings, tranexamic acid, aminocapric acid ferric sulphate and silver nitrate, which may be used to control immediate postoperative bleeding.

A recent systematic review published in 2016,6 concluded that there is currently evidence from small studies which suggests that surgical site irrigation with tranexamic acid followed by mouthwash during the first postoperative week is safe and may reduce the risk of bleeding after minor surgeries on anticoagulants patients.

Until more evidence is available: ‘Prevention is the best cure.’ (Desiderius Erasmus)

References

van Galen KP, Engelen ET, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, van Es RJ, Schutgens RE . Antifibrinolytic therapy for preventing oral bleeding in patients with haemophilia or Von Willebrand disease undergoing oral or dental extractions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 12:CD011385 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.

ockhart PB, Gibson J, Pond SH, Leitch J . Dental management considerations for the patient with an acquired coagulopathy. Part 1: Coagulopathies from systemic disease. Br Dent J 2003; 195:439–445.

Carter G, Goss A, Lloyd J, Tocchetti R . Tranexamic acid mouthwash versus autologous fibrin glue in patients taking warfarin undergoing dental extractions: a randomized prospective clinical study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 61:1432–1435.

Al-Belasy FA, Amer MZ . Hemostatic effect of n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (histoacryl) glue in warfarin-treated patients undergoing oral surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003; 61:1405–1409.

Weltman NJ, Al-Attar Y, Cheung J, Duncan DP, Katchky A, Azarpazhooh A, Abrahamyan L . Management of dental extractions in patients taking warfarin as anticoagulant: A systematic review. J Can Dent Assoc 2015; 81:f20.

de Vasconcellos SJ, de Santana Santos T, Reinheimer DM, Faria-E-Silva AL, deMelo MF, Martins-Filho PR . Topical application of tranexamic acid in anticoagulated patients undergoing minor oral surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2017; 45:20–26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Luisa Fernandez Mauleffinch, Managing Editor, Cochrane Oral Health Group, School of Dentistry, The University of Manchester, JR Moore Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK. E-mail: luisa.fernandez@manchester.ac.uk

Sumanth KN, Prashanti E, Aggarwal H, Kumar P, Lingappa A, Muthu MS, Kiran Kumar Krishanappa S. Interventions for treating post-extraction bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, Issue 6. Art. No. CD011930. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD011930.pub2.

This paper is based on a Cochrane Review published in the Cochrane Library 2016, issue 6 (see www.thecochranelibrary.com for information). Cochrane Reviews are regularly updated as new evidence emerges and in response to feedback, and the Cochrane Library should be consulted for the most recent version of the review.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Veitz-Keenan, A., Keenan, J. No evidence available on best therapies for postextraction haemorrhage. Evid Based Dent 18, 52–53 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401241

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6401241