Abstract

Data Sources

Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, International Association for Dental Research abstracts and reference lists of retrieved articles were searched, and contact made with content experts.

Study selection

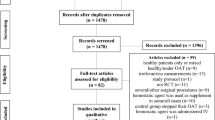

Studies were selected independently by two reviewers. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) were selected if: they compared the effects of continuing a regular dose of warfarin with the effects of discontinuing (or modifying) the dose on the incidence of bleeding; the study group participants were people undergoing dental procedures who also had thromboembolism (arterial or venous); and the outcome assessed was postoperative bleeding (major, clinically significant nonmajor, or minor). Study quality was assessed using the Jadad scale.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction was carried out by three reviewers independently. Meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model.

Results

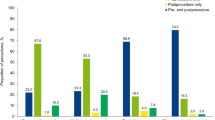

Five RCT (553 patients) met the inclusion criteria. Compared with interrupting warfarin therapy (either partial or complete), peri-operative continuation of warfarin at the patient's usual dose was not associated with an increased risk for clinically significant nonmajor bleeding [relative risk (RR), 0.71; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.39–1.28; P 0.65; I2 0%) or an increased risk for minor bleeding (RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 0.90–1.58; P 0.22; I2 0%).

Conclusions

Continuing the regular dose of warfarin therapy does not seem to confer an increased risk of bleeding compared with discontinuing or modifying the warfarin dose in people undergoing minor dental procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

There has been a significant increase in the number of people taking oral anticoagulation therapy over the past 10 years. In the UK, this has largely been the result of the publication of Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline (SIGN) guideline no.36, Antithrombotic Therapy (published in March 1999).1 Meanwhile, dental surgeons have shown a reluctance to perform even simple extractions on this group of patients because of the fear of complications, in particular postextraction bleeding.

This review examines five papers, one published as long ago as 1993, all of which have problems associated with their design. None of them described adequately all three of the parameters studied, nor randomisation, method of blinding and the reason for patient withdrawal. It is difficult, if not impossible, to compare the results described in these papers. The overall nonmajor bleeding rate is 5.5% for people continuing to take warfarin, but the paper by Souto and colleagues2 had a nonmajor bleeding rate of 24%. Those authors also reported that 33% of the control group reported a nonmajor bleeding episode.

The National Patient Safety Agency published a series of papers entitled Actions that can make anticoagulant therapy safer in March 2007 (www.npsa.nhs.uk/nrls/alerts-and-directives/alerts/anticoagulant/), including a section on the management of individuals who require dental surgery. The North West Medicines Information Centre section also updated their guidance at the same time.3 These publications were not identified as the search strategy was not designed to identify grey literature.

A major problem associated with the treatment of people who are taking oral anticoagulation is that warfarin interacts with many other medications, and even foods. A comprehensive list is available in the British National Formulary. The aim of treatment is to maintain the INR (International normalised ratio of prothrombin time) within a set range but it has been suggested that, at any particular time, up to 30% of patients have an INR outside their therapeutic range. People who are about to undergo oral surgery procedures should therefore have their INR checked no more than 3 days prior to treatment. This paper by Nematullah et al., on the contrary, focuses on the trial evidence of warfarin use in patients undergoing elective dental procedures and does not make any recommendations regarding pretreatment checks.The analysis does support the widely held view that interruption of patients' oral anticoagulation is not required; within the UK, however, a pretreatment INR check is recommended before any extraction or minor surgical procedure.

References

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Antithrombotic Therapy. Guideline no.36. Edinburgh: SIGN 1999.

Souto JC, Oliver A, Zuazu-Jausoro I, Vives A, Fontcuberta J . Oral surgery in anticoagulated patients without reducing the dose of oral anticoagulant: a prospective randomised study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 54: 27–32.

Surgical Management of the Primary Care Dental Patient on Warfarin. Liverpool: North West Medicines Information Centre.2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: Dr Susan E Sutherland, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Room H-126, 2075 Bayview Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M4N 3M5, Canada. E-mail: susan.sutherland@sunnybrook.ca

Nematullah A, Alabousi A, Blanas N, Douketis JD, Sutherland SE. Dental surgery for patients on anticoagulant therapy with warfarin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Can Dent Assoc 2009; 75: 41

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brewer, A. Continuing warfarin therapy does not increased risk of bleeding for patients undergoing minor dental procedures. Evid Based Dent 10, 52 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400653

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400653