Abstract

To date, studies assessing whether the information given to people about screening tests facilitates informed choices have focussed mainly on the UK, US and Australia. The extent to which written information given in other countries facilitates informed choices is not known. The aim of this study is to describe the presentation of choice and information about Down's syndrome in written information about prenatal screening given to pregnant women in five European and two Asian countries. Leaflets were obtained from clinicians in UK, Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Czech Republic, China and India. Two analyses were conducted. First, all relevant text relating to the choice about undergoing screening was extracted and described. Second, each separate piece of information or statement about the condition being screened for was extracted and then coded as either positive, negative or neutral. Only Down's syndrome was included in the analysis since there was relatively little information about other conditions. There was a strong emphasis on choice and the need for discussion about prenatal screening tests in the leaflets from the UK and Netherlands. The leaflet from the UK gave most information about Down's syndrome and the smallest proportion of negative information. By contrast, the Chinese leaflet did not mention choice and gave the most negative information about Down's syndrome. Leaflets from the other countries were more variable. This variation may reflect cultural differences in attitudes to informed choice or a failure to facilitate informed choice in practice. More detailed studies are needed to explore this further.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Choice is highly valued in most societies and increasingly features in the provision of health care in developed countries, reflecting broader political changes in the growing power of the consumer as well as the erosion of professionals’ power. The need for such choices to be informed is also increasingly emphasised. This is particularly evident in the context of genetic counselling, with a summary of 51 national and international guidelines for genetic counselling emphasising the importance of patient autonomy and non-directive information giving in this context (http://www.eurogentest.org/web/info/public/unit3/guidelineswp12.xhtml accessed 02.10.2006).

Leaflets can be an important source of information for people offered prenatal screening tests. In order to make informed choices about whether or not to undergo prenatal screening, these need to make parents aware that they have a choice and to include accurate and balanced information about the condition for which screening is being offered. However, the quality of written information given to those offered a variety of screening tests is often poor. The emphasis is often upon encouraging people to undergo screening rather than facilitating informed choices.1 For example, an analysis of leaflets about neonatal testing from the UK, USA and Australia found that few facilitated informed choice:2 although the majority informed parents of the benefits of screening, few mentioned that undergoing such tests was a parental choice.

Two studies which critically evaluated leaflets given to pregnant women in the UK prior to undergoing serum screening concluded that the quality of the leaflets was generally poor.3, 4 Bryant et al3 described written information women were given about Down's syndrome. About a fifth of the 80 leaflets analysed gave no information about the condition at all. Those that did provide such information provided negative information about Down's syndrome. Perceptions of the severity of a condition are important in the decision to terminate a foetus with an anomaly.5 Given that the information provided appears to influence these decisions,6 the presentation of information about a condition is a key component of facilitating informed choice.

To date, studies evaluating the extent to which the information given to people about screening programmes facilitates informed choices have focussed on the UK, US and Australia.2, 3, 4, 7 The extent to which written information for people offered screening is likely to facilitate informed choice in other countries is not known. The aim of this study is to describe the presentation of choice and information about Down's syndrome in written information given to pregnant women about prenatal screening in Europe and Asia. The seven countries studied are: UK, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, Czech Republic, China and India. These countries were selected from those participating in the SAFE Network of Excellence (http://safenoe.org/cocoon/safeorg) and chosen to represent Northern, Southern and Eastern Europe, and Asia.

Methods

The leaflets

We contacted participants in the SAFE network of excellence to ask them to provide written information on prenatal screening or the contact details of a colleague who might be able to provide such information. We received just one relevant leaflet each from the Czech Republic, India, China and Spain. Since we received two from Italy, the Netherlands and the UK, we selected the leaflet for national distribution from the UK, and the leaflets, which focussed more strongly on screening for Down's syndrome (rather than prenatal diagnosis or genetic testing) from Italy and the Netherlands. Details of the leaflets are given in Table 1.

Analysis

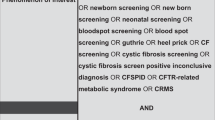

The number of sentences in each leaflet are shown in Table 1 (not including titles, headings, and pictures). Leaflets not in English were translated by a commercial translation agency using qualified translators. Two aspects of the leaflets were analysed. First, all relevant text relating to choice to undergo prenatal screening tests was extracted. This is presented in Table 2 and is described narratively. Second, each separate piece of information or statement about the condition for which screening was being conducted was extracted and then coded as either positive, negative or neutral. Only Down's syndrome was included in the analysis since there was relatively little information about other conditions. Information included the nature of Down's syndrome, its symptoms, treatment, quality of life and life expectancy for individuals with the condition. The classification used in the current study was based on the criteria used in earlier studies which described written information about the condition for which screening was being conducted in prenatal screening leaflets.3, 7 Examples of positive information were: ‘some people with Down's syndrome enjoy good health’ and ‘most people with Down's syndrome live to be over 50 years of age, some live to be over 70’. Examples of negative information were: ‘severe mental handicap (IQ<50) will result in most cases’ and ‘Down's syndrome is the single most common cause of mental disorder’. Examples of neutral information are: ‘there is no such thing as a typical person with Down's syndrome’ and ‘people vary’. Information about basic genetics and the risk of having a child with the condition were excluded. Each piece of information was coded independently by two coders (SH and AH). Agreement was good (97%, 57/59). Both disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Results

With the exception of the leaflet from the UK, which was produced by the UK National Screening Committee for national distribution, all leaflets were produced and distributed by a single centre. Some leaflets focussed entirely on prenatal screening for Down's syndrome (e.g. Czech Republic) whilst others included only a sub-section on this (e.g. Netherlands). The leaflets varied considerably in length, from 176 (UK) to 30 sentences (Spain).

Choice

There was a strong emphasis on choice and the need for discussion about prenatal screening tests in the leaflets from the UK and the Netherlands (Table 3). No prenatal screening tests were unequivocally recommended. Both leaflets clearly stated that their purpose was to give parents the information they needed to decide whether or not to undergo prenatal screening for Down's syndrome and encouraged them to ask questions. The leaflet from the Netherlands also mentioned that prenatal tests are only intended for women at increased risk of foetal anomalies. By contrast, choice was mentioned only briefly in the Italian leaflet and not at all in the Spanish leaflet. In the latter, Down's syndrome screening was clearly recommended. Similarly, the leaflet from the Czech Republic recommended screening tests and parents were informed that the test was acceptable and popular in other countries. Choice was mentioned briefly in the leaflet from India. The triple test was described as voluntary and choice was mentioned regarding termination of a pregnancy affected by Down's syndrome. The Chinese leaflet did not mention choice: women were informed that they should undergo the test, which was described as mandatory in the US and most other Western countries.

Information on Down's Syndrome

Overall, the seven leaflets contained 59 pieces of information or statements about Down's syndrome (Table 2). Nearly three-quarters of these were negative, with an almost equal amount of positive and neutral information. The leaflet from the UK contained the most information about Down's syndrome and contained the lowest proportion of negative information. Although there was a strong emphasis on choice in the Dutch leaflet, there was relatively little information about Down's syndrome, which tended to be negative. The Spanish leaflet gave only one piece of information about the condition, which was negative. In the Italian leaflet the information about Down's syndrome was largely negative. The leaflets from the Czech Republic and India gave only negative information about Down's syndrome. The Chinese leaflet presented a substantial amount of negative information about Down's syndrome.

Discussion

Giving written information is an important component of facilitating an informed choice process. In order to make informed choices about whether or not to undergo prenatal screening, women need to be informed that they have a choice and be given accurate and balanced information about the condition being screened for. Although the need for women to make informed choices regarding undergoing prenatal screening is emphasised in international guidelines (http://www.eurogentest.org/web/info/public/unit3/guidelineswp12.xhtml accessed 02.10.2006), there is considerable variability in the extent to which the leaflets we reviewed are likely to facilitate informed choice. Such variability may reflect differences in knowledge about Down syndrome in each society, cultural differences in how information is distributed and/or differences in the beliefs of health care providers about the value of informed choice in prenatal screening.

The leaflets from the UK and the Netherlands suggest that informed choice regarding prenatal screening is highly valued in these countries. Nevertheless, the extent to which these leaflets actually facilitate informed choices is not known. The informed choice agenda in the UK, for example, may be more rhetoric than reality. A study of the effectiveness of 10 ‘informed choice’ leaflets for pregnant women in Wales found that they did not promote informed choice.8 For example, many were withheld from women, or lost amidst other written information, and there was little opportunity for discussion. The amount of positive information about Down's syndrome in the written information from the UK may reflect social attitudes towards this condition in the UK and/or the influence of The Down's Syndrome Association, a large national charity which champions the rights of people with Down's syndrome and strives to improve knowledge of the condition. Whether or not the information about Down's syndrome in the leaflet from the UK is ‘balanced’ is uncertain as there is no agreement of what this should comprise.9 Although the Dutch leaflet placed a strong emphasis on encouraging choice, there was little information on Down's syndrome. This may have been because a range of other chromosome anomalies were also described.

The leaflets from Southern Europe and Asia suggest that choice in relation to prenatal screening may not be as highly valued in these countries as it is in Northern Europe. People differ in the value they assign to being actively involved in decisions about their health care.10 However, it is also possible that participants would value choice if it was on offer. Structural factors in the design of screening programs are also likely to explain some of the variation in the content of the leaflets. In the UK, prenatal screening is routinely offered to pregnant women and is available free at the point of delivery as part of the National Health Service (NHS), or women can pay to have prenatal screening tests privately. The NHS has recently launched an initiative to ensure that pregnant women are given sufficient information to make informed choices about whether or not to undergo such tests.11

In the Netherlands, prenatal screening for Down's syndrome is offered to pregnant women aged 36 and over. Midwives, GPs, or gynaecologists refer eligible women who want testing to an academic hospital or its satellites for further information about the implications of prenatal testing. Since the enactment of the Population Screening Act in 1996, the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport is responsible for issuing a permit for specific types of population screening, such as screening for serious conditions which can neither be treated nor prevented. For this reason, a formal permit is required for any screening programme for foetal congenital anomalies, since, from the legal point of view, termination of pregnancy is not considered prevention or treatment. For women aged 36 and over, prenatal tests are free of charge. Women aged under 36 years will be given information about the pros and cons of screening for Down's syndrome by a physician, midwife or obstetrician, but only if they wish to be informed. If they then want to undergo screening they have to pay for the test. However, expenses for any subsequent, invasive test are reimbursed. It is expected that in 2007 the Minister will grant a permit for prenatal screening to each academic hospital, thereby opening the way to a national prenatal screening programme.

In Italy, there is no national screening programme for Down's syndrome. Different programmes are offered in 20 autonomous regions. In some regions, screening for Down's syndrome is free of charge, while in others, parents have to pay for the test. Women are usually informed about prenatal tests during their first appointment with an obstetrician. Often written information is not given at this stage. Such information is usually given when women attend for tests and women are asked to sign a consent form indicating that they understood the meaning of this. Obstetricians tend to suggest that women over 35 years of age have invasive tests.

In Spain, population based screening for DS has not been widely introduced, except in some areas such as Catalonia and Majorca Island, where specific programs were started in the early nineties. A uniform policy has not been established or recommended by the National Health Service and most initiatives have been undertaken by only a few of the 17 Spanish autonomous regions. Information about the tests is offered to pregnant women by health professionals (Obstetricians, Midwives, Obstetrical nurses and rarely by clinical geneticists). Information on DS screening for pregnant women (written or otherwise) is not widely available before the test is offered.

In the Czech Republic, currently, all pregnant women are routinely offered the triple, or more often, the double test and ultrasound for foetal anomalies at 20 and 30 weeks gestation. All these methods are traditionally fully paid for by health insurances. From the beginning of the new millennium, screening in the first trimester has been available.

India is in a transitional phase as far as genetic services are concerned. There is no uniform policy about prenatal screening for Down's syndrome and there is no national screening program. Such tests are now being offered by some, mostly private, laboratories in large cities. Obstetric services in the peripheral centres do not have the facilities for antenatal biochemical screening. Physicians usually give verbal rather than written information about prenatal screening tests. However, many doctors practicing obstetrics are not believed to have the knowledge regarding the availability, utility and interpretation of these tests.

In China, there is no national prenatal screening programme. Couples need to pay for any prenatal screening tests they undergo. Parents are usually given written information and asked to complete a consent form before undergoing prenatal screening. Knowledge about Down's syndrome and prenatal screening is generally poor. Furthermore, there are too few professionals delivering obstetrics care in relation to the large patient population, which means there is not enough time to give balanced information about Down's syndrome. Most importantly, China has no national system to support those families with children with Down's syndrome. With no financial support from the government, the birth of such a child can be very difficult for the family.

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to describe and compare how choice regarding prenatal screening is presented in countries outside the US and Northern Europe. It has, however, three main limitations. First, the single leaflets may not be representative of those available in these countries. We initially aimed to obtain leaflets from a range of centres in each country. However, obtaining this information proved to be extremely difficult in most countries and impossible in others. We made over 150 requests for leaflets. Many people did not respond, or replied informing us that they did not provide such information in a written format. Second, our analysis focussed only on how choice and the condition being screened for were presented. A number of other criteria need to be met for written information to facilitate informed choices, including the readability of the material and checking understanding, how risk information is presented, whether or not women are informed of the limitations of screening (including false positives and false negatives) and the possible consequences of an increased risk result, and encouraging deliberation about whether this is a choice an individual wishes to make. We did not interpret these findings. Third, women may be given verbal information about prenatal screening tests either alongside or instead of written information. Discussion with health professions can either facilitate or pose considerable barriers to realising informed choice. For example in the UK, counselling from midwives or obstetricians may not reflect the informed choice policy apparent in written information. Owing to lack of time, practitioners may rely on the leaflets that women have been sent prior to attending the clinic.12 Whether or not health professionals, in countries with written information that does appear to support an informed choice policy, encourage informed decision-making in their patients is not known. Nevertheless, written information gives an indication of attitudes towards informed choice in these countries.

Despite these limitations, the current study raises questions regarding the value attached to informed choice in different countries. It may not be appropriate to recommend a Northern European informed choice agenda for other countries. For example, the Northern European informed choice model is based on individual autonomy which may not be appropriate in collectivist cultures.13 Little is known of the extent to which making informed rather than uninformed choices confers benefits. If there are few benefits, it may not be appropriate to divert resources to facilitating informed choice. The data presented here are a first step towards exploring the different values attached to informed choice across the world.

References

Marteau TM, Kinmonth Al : Screening for cardiovascular risk: public health imperative or a matter for individual informed choice? BMJ 2002; 325: 78–80.

Hargreaves K, Stewart R, Oliver S : Newborn screening information supports public health more than informed choice. Health Educ J 2005; 64: 110–119.

Bryant LD, Murray J, Green JM, Hewison J, Sehmi I, Ellis A : Descriptive information about Down's syndrome: a content analysis of serum screening leaflets. Prenat Diagn 2001; 21: 1057–1063.

Murray J, Cuckle H, Sehmi I, Wilson C, Ellis A : Quality of written information used in Down's syndrome screening. Prenat Diagn 2001; 21: 138–142.

Evans MI, Sobiecki MA, Krivchenia EL et al: Prenatal decisions to terminate/continue following cytogenic prenatal diagnosis: ‘what’ is still more important than ‘when’. Am J Med Genet 1996; 61: 353–355.

Hall S, Abramsky L, Marteau TM : Health professionals’ reports of information given to parents following the prenatal diagnosis of sex chromosome anomalies and outcomes of pregnancies: a pilot study. Prenat Diag 2003; 23: 535–538.

Loeben GL, Marteau TM, Wilfond BS : Mixed messages: presentation of information in cystic fibrosis-screening pamphlets. Am Hum Genet 1998; 63: 1181–1189.

Stapleton H, Kirkham M, Thomas Q : Qualitative study of evidence based leaflets in maternity care. BMJ 2002; 323: 1–6.

Williams C, Alderson P, Farsides B : What constitutes ‘balanced’ information in the practitioners’ portrayals of Down's syndrome? Midwifery 2002; 18: 230–237.

Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D et al: Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA 1997; 277: 1485–1492.

Barrett A : NHS publicises advances in antenatal and neonatal screening programmes. BMJ 2005; 331: 180.

Williams C, Alderson P, Farsides B : What constitutes balanced information in the practitioners’ portrayal of Down's syndrome? Midwifery 2002; 18: 230–237.

Hofstede G : Culture's Consequences. London, Sage Publications, 1984.

Acknowledgements

The work reported here was conducted as part of the Special Non-Invasive Advances in Fetal and Neonatal Evaluation (SAFE) Network of Excellence (LSHB-CT-2004-503243). The authors acknowledge the support from the European Commission who funded this network.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hall, S., Chitty, L., Dormandy, E. et al. Undergoing prenatal screening for Down's syndrome: presentation of choice and information in Europe and Asia. Eur J Hum Genet 15, 563–569 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201790

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201790

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluation of Patient Education Materials: The Example of Circulating cell free DNA Testing for Aneuploidy

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2015)

-

Are Indian Parents of Children with Down Syndrome Engaged in the Blame Game?

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2013)

-

Measuring attitude toward social health insurance

The European Journal of Health Economics (2012)

-

What is a “Balanced” Description? Insight from Parents of Individuals with Down Syndrome

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2012)