Key Points

-

Overall job satisfaction among this group of dentists was good.

-

Although stress is a feature of dentistry, many factors contribute to job satisfaction.

-

Job satisfaction may be improved by developing an area of special interest by further training.

-

Increasing the amount of treatment provided privately, and relocating to non-rural locations, may also improve job satisfaction. This would have obvious implications for the future of dentistry in the NHS, and for patients living in rural areas.

Abstract

Objectives To assess the level of job satisfaction among general dental practitioners from one area of England, and to assess the association of various personal and work related factors with job satisfaction.

Design Postal questionnaire survey.

Setting General dental practices in South Staffordshire, Wolverhampton and Dudley, England.

Method An anonymous questionnaire posted to all 396 registered dentists in the above areas.

Results A 75% response rate was achieved. Data were analysed using non–parametric statistics for any significant differences in the scores for stress, respect, overall professional satisfaction, quality of life and overall job satisfaction according to the different demographic groupings of the dentists (alpha =0.05). Dentists with an area of special interest had higher scores in all categories except quality of life. Overall job satisfaction was higher among private dentists, and those in group practices and in non-rural locations. The highest bi-variate correlation occurred between overall job satisfaction and overall professional satisfaction, delivery of care, income, respect and professional time.

Conclusions Job satisfaction was judged to be good among this group. Stress was the factor associated with the greatest dissatisfaction. This survey produced similar results to preceding US studies, and suggests ways of improving job satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dentistry has frequently been described as a stressful occupation, and associated with greater incidence of ill health, alcoholism, and suicide than other professions. Such assertions have entered the folklore of society.1,2 Historical data from the USA concerning male dentists has shown that they live longer than the average white male population, but have approximately twice the average suicide rate of white males. When compared with similar professionals such as medical practitioners however, there appears to be no difference.3,4 While dentists may not suffer more stress than is experienced within comparable careers, stress may be a significant feature of the job.5 Severe stress can lead to the phenomenon of burnout and the probable premature end to a career in which the individual and society has invested considerable time and money.6 Stress and job satisfaction have a complex inter–relation. There has been abundant research on the stressors of a dental career, and associated levels of burnout.7,8,9 However, job satisfaction has received less attention in the UK and as dentistry has undergone many changes imposed by successive governments, developments within dentistry, and changes in patients' expectations, it is pertinent to monitor what effects these changes have had on dental career satisfaction. By discovering what personal and job factors are associated with career satisfaction, it may be possible to provide guidance to dissatisfied practitioners, and suggest ways in which dental training may better prepare future dentists for their chosen vocation. A more contented workforce should directly benefit society, and prevent the waste of personal and national resources, which is the result of burnout and premature retirement.

Aims

-

To assess the level of job satisfaction among general dental practitioners working within one area of England.

-

To assess the association of various personal and work related factors with job satisfaction.

Method and materials

A confidential questionnaire was designed and piloted among 15 general dental practitioners working in neighbouring areas to the target group. No changes were deemed necessary following this phase, and the questionnaire was sent to all the practitioners on the dental list for South Staffordshire, Wolverhampton and Dudley in 2003 (total 396). This region was chosen as it comprised rural as well as urban areas, and, as the first author lived in this region, it was known that a range of practice types existed ie accepting patients for treatment under private contract or under the terms of the National Health Service. It was therefore hoped that this region would provide adequate numbers in each of the categories contained in the questionnaire to allow meaningful analysis of their impact on job satisfaction; and that findings from this study therefore may be extrapolated to the country as a whole. A stamped return envelope and covering letter was included assuring respondents that the information given would be non-attributable.

The questionnaire was based on an American survey instrument, which was modified slightly with regard to language and terminology to make it more appropriate for British dentists. The original questionnaire had been examined for consistency and internal validity using Cronbach's alpha, and has been used successfully by two separate groups of investigators in the United States.10,11 The first part of the questionnaire would gather information on personal and work-related characteristics. The second part consisted of 11 sections containing 47 statements relating to different facets of work; respondents were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with these statements on a five-point Likert type scale. Some questions and sections were worded such that agreement indicated increasing job satisfaction and a higher score; others were worded in an opposite fashion. Where necessary, scores for some questions were reversed on entering the data, such that a high score would still indicate higher job satisfaction. A further section asked the participants to rate their quality of life with regard to six factors, again using a five-point scale. An additional section was added enquiring into the dentists' hobbies, and other careers that had been considered before and since becoming a dentist.

Results

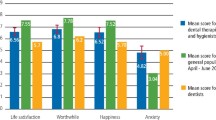

After the first and one further mailing, 297 forms were returned, a response rate of 75%. Twenty-one incomplete forms were rejected leaving 276 (69%) for analysis. The information was analysed using a computer statistical package; SPSS V10 (SPSS Inc.). As the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used for analysis. Tables 1 and 2 list the relative proportions of respondents according to the descriptors in the first section of the questionnaire. The data from the second section were used to produce a satisfaction score for each of the 11 sections and an overall job satisfaction score. Each Likert score (1 – 5) was converted to a percentage score (0% – 100%). High scores indicated high job satisfaction. To aid interpretation, three groups were established according to the scoring system. A score within the lower range of 0% to 33% was categorised as dissatisfied, between 33% and 66% as neutral, and scores above 66% as satisfied. The proportions of dentists within each group for each facet of job satisfaction are shown in Figure 1. Although only two (0.7%) dentists are within the dissatisfied group for their overall job satisfaction, the majority are in the neutral category, and 71 (25.7%) are in the satisfied group for overall job satisfaction. With regard to overall professional satisfaction, 94 (34.1%) are satisfied and 62 (22.5%) are dissatisfied. The job facet 'stress' was associated with the highest proportion of dissatisfaction and the lowest of satisfaction.

Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess whether there were any significant differences discernible in the scores for the job facets respect, stress, overall professional satisfaction, overall job satisfaction, and quality of life, among the different practice and personal groups identified in the opening section of the questionnaire (alpha = 0.05). The results shown in Table 3 indicate few significant differences in these job facet scores between most groups. The most significant differences for all facets (except quality of life) are seen between those who have an area of special interest, (and higher satisfaction scores) and those who do not (special interest — further training or skill in one or more aspects of dentistry, but not necessarily to the level required for admission to the UK General Dental Council's specialist lists). Those who provide most treatment outside the National Health Service (NHS) have significantly higher scores for overall professional satisfaction than those who provide some or all of their treatment under the NHS, and a higher score for quality of life than those who provide most of their treatment under the NHS. Quality of life is also judged to be worse by practice principals. Those who work single-handed, and those whose practices are in rural areas have significantly lower scores for overall job satisfaction than those who are in group practices or who practise in the suburbs or cities.

Further analysis using Chi-square tests identified that there was no significant association between the practice location and whether or not the practitioner had a special interest (p=0.883). There was a significant association between the location of the practice, and whether the dentists worked in a single-handed or a group practice, with a greater proportion of dentists working single-handed in rural and suburban areas than in town or city centres (p=0.003). Spearman's rank order correlation co-efficients were calculated to establish the strength of associations among the facets of job satisfaction, and associations between some of the aforementioned dentist and work related factors and job facets. The variables having the highest bi-variate correlation with the total score (ie job satisfaction) were overall professional satisfaction, delivery of care, income, respect and professional time. There was moderate correlation with stress, quality of life, personal time and patient relations.

The answers to the component questions in each of the 11 job facet sections of the questionnaire were also evaluated to aid interpretation. Within the section 'overall professional satisfaction', 53.6% disagreed that they wished to change career, and 56.5% agreed that they were satisfied with their career in dentistry. Approximately equal proportions of respondents would encourage (35.5%) as would not encourage (37.7%) their child to become dentists, while 67% agreed that they wished to reduce the hours which they worked. Within 'delivery of care', a large proportion of the dentists were positive about their confidence to deal with dental problems, the technical quality of their work, and their opportunities to provide quality care. Approximately one third agreed and one third disagreed that they were able to practise dentistry the way they wanted. Over half (53.6%) agreed that the threat of litigation had affected their treatment decisions; 24.6% disagreed with this statement.

Stress was initially identified as the job facet associated with the greatest proportion of dissatisfaction. Of the three statements in this section, the greatest difference in the proportions who were in agreement compared with those who disagreed was in regard to the statement that 'working in the NHS is increasingly more stressful'; 88% agreed or strongly agreed, only 6.2% disagreed or strongly disagreed. The end section of the questionnaire asked what other careers had been considered before becoming a dentist, and which would be seriously considered now. Of the 210 dentists who responded to the first question, the majority 46% had considered medicine. Other choices were veterinary medicine (10%), engineering (8%), pharmacy (8%), and law (8%). Smaller groups mentioned a specific science, or other health related training (eg physiotherapy, optician) and similar numbers had non-health related training in mind (eg pilot, banking, architect). There were 139 responses to the enquiry as to which career might seriously be considered now. Nineteen per cent would choose law, 10% accounting or a finance related career. Equal numbers (8%) would now select medicine, or an alternative career in dentistry (eg working abroad, or teaching). There were a wide variety of alternatives mentioned by individuals from health related jobs to professional sports and horticulture.

Discussion

The response rate from this research is satisfactory but as it was anonymous, it was not possible to examine for any differences between the responders and the non-responders. It is the authors' opinion that dentists who were dissatisfied with their job would be less likely to participate in this survey, and therefore the low level of dissatisfaction seen here is probably an underestimate of the true picture. This survey relates only to one region of England, and a different picture may emerge in other areas. Nevertheless, the region selected allowed the inclusion of respondents from within all of the demographic categories defined in the questionnaire, and its findings may be more generally applicable as a result. More representatives in some categories eg VDPs would be required to permit a more robust analysis. Multiple or larger scale studies in several areas could achieve this. Bearing these limitations and those common to all such survey methods in mind, it may be seen that a greater proportion of the dentists are dissatisfied with the stress element of their job than with any of the other factors investigated. However, stress is only moderately correlated with overall job satisfaction, which is dependent on many factors.

The workers in the USA who used the same survey instrument found that there were few demographic and practice characteristics which related to job satisfaction.10,11 However, in both the American surveys, older practitioners registered higher overall satisfaction scores than younger dentists, and the lower satisfaction scores seen among females were, with further analysis, determined to be related to age rather than gender. In these surveys in Kentucky and California, no differences were seen between rural and urban based dentists. Our survey found no age or sex related differences, but identified lower overall satisfaction among rural dentists than in those who practised in a suburban or city location. However, only 20 (7%) of our respondents worked in a rural location. With a larger representative group, such a finding may not occur, and is an area for further study. In the UK, there have been reported difficulties in attracting dentists into rural and country areas. If there is lower job satisfaction among such dentists, then by ascertaining what specific factors associated with working in a rural environment contribute to low job satisfaction, it may be possible to make a country practice more attractive.

Factors not examined previously were whether the dentist was providing mainly NHS or private treatment and whether they had an area of special interest. Private dentists had significantly higher overall job satisfaction, and quality of life scores than NHS dentists, and those with a special interest had significantly higher scores for respect, overall professional satisfaction, overall job satisfaction, and lower stress scores than those without such an interest. This would strongly suggest that to improve job satisfaction, practitioners should identify their preferred areas of dentistry, and endeavour to gain more expertise and training, while avoiding those areas in which they have less interest or ability. It is also suggested that another strategy to gain greater job satisfaction is to leave the NHS. At a time in which the UK government is committed to providing universal access to NHS dentists, perhaps this indicates that changes to the NHS system should be explored to enable greater retention of NHS dentists. Indeed, at the time of writing, changes to the current remuneration scheme are being proposed. A follow-up survey in the near future could help to assess the effect of these changes on job satisfaction among NHS practitioners.

In contrast to the US surveys, practice owners (principals) had significantly lower quality of life scores than non-owners (associates, assistants and vocational dental practitioners). Those practising single-handedly (ie without other dentists in the same establishment) had lower scores for overall professional satisfaction.

The original alternative career choices were dominated not surprisingly by medicine and similar healthcare professions. It is encouraging to see that, from the individual questions in the professional job satisfaction section, only 18% were not satisfied with their career in dentistry, however 27% wanted to change careers. Equal proportions would encourage as would not encourage their children into dentistry (37%). Why so many selected law or a financially related profession as an alternative career that they would now seriously consider, is open to debate. Possibly it relates to wanting to move away from any health-related job, having been dissatisfied with one health-related career. It may also be that these alternatives are seen as more financially rewarding with less associated stress ('the grass is always greener'?).

Conclusions

For this group of dentists, job satisfaction was judged to be good. Stress was the factor associated with the greatest dissatisfaction, however job satisfaction accrues from many elements. This survey produced similar results to preceding US studies. Overall, job satisfaction showed a high correlation with overall professional satisfaction, delivery of care, income, respect and professional time. Significantly higher job satisfaction scores were identified amongst dentists with a special area of interest, those practising privately, and in non-rural locations.

References

Howard JH, Cunningham DA, Rechnitzer P, Goode RC . Stress in the job and career of dentists. J Am Dent Assoc 1976; 93: 630–636.

Jackson E, Mealiea WL . Stress management and personal satisfaction in dental practice. Dent Clin N Am 1977; 21: 559–576.

Bureau of Economic Research and Statistics. Mortality of dentists, 1968 to 1972. J Am Dent Assoc 1975; 90: 195.

Orner G, Mumma RD . Mortality study of dentists; final report, prepared for the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Philadelphia: Temple University Health Sciences Center, School of Dentistry, 1976.

Cooper CL, Watts J, Kelly M . Job satisfaction, mental health and job stressors among general dental practitioners in the UK. Br Dent J 1987; 162: 77–81.

Maslach C . Burnout - the cost of caring. P3. New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1982.

Wilson RF, Coward PY, Capewell J, Laidler TL, Rigby AC, Shaw TJ . Perceived sources of occupational stress in general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 1998; 10: 499–502.

Murtomaa H, Haavio-Mannila E, Kandolin J . Burnout and its causes in Finnish Dentists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1990; 18: 208–212.

Gorter RC, Albrecht G, Hoogstraten Eijkman MAJ . Measuring work stress among Dutch dentists. Int Dent J 1999; 49: 144–152.

Shugars DA, DiMatteo RM, Hats RD, Cretin S, Johnson JD . Professional satisfaction among California general dentists. J Dent Educ 1990; 54: 661–669.

Wells A, Winter PA . Influence of practice and personal characteristics on dental job satisfaction. J Dent Educ 1999; 63: 805–812.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gilmour, J., Stewardson, D., Shugars, D. et al. An assessment of career satisfaction among a group of general dental practitioners in Staffordshire. Br Dent J 198, 701–704 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812387

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4812387

This article is cited by

-

Perceptions of dental health professionals (DHPs) on job satisfaction in Fiji: a qualitative study

BMC Health Services Research (2022)

-

Supporting dentists' health and wellbeing - workforce assets under stress: a qualitative study in England

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Key determinants of health and wellbeing of dentists within the UK: a rapid review of over two decades of research

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

A study to explore if dentists' anxiety affects their clinical decision-making

British Dental Journal (2017)

-

Career satisfaction and work-life balance of specialist orthodontists within the UK/ROI

British Dental Journal (2017)