Key Points

-

This paper looks at GDPs' perceptions of what made a good oral medicine referral communication and how this compared with the views of an oral medicine service provider.

-

Differing perceptions of what makes an ideal referral and how referrals were handled were apparent.

-

The results suggest that a lack of time, confidence in making a diagnosis and for some, lack of administrative support were barriers to achieving an ideal referral communication.

-

No single mechanism for improving the quality of referrals to this service were apparent. Suggestions included standardised referral proformas and access to improved IT systems.

Abstract

The quality and content of referral letters are important for prioritisation of patients who may have oral cancer. Referrals letters to the Oral Medicine Clinic at Birmingham Dental Hospital were analysed and practitioners interviewed. Whilst acceptable for general purposes, most letters did not contain sufficient information to allow effective prioritisation. Interviews disclosed a misunderstanding amongst practitioners about the way in which referrals were handled. A number of barriers to increasing the information included in letters were identified. Referral guidelines and a standardised proforma might help improve the ability of the service to operate a fast-track system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Referral letters are frequently the only method by which information is transmitted between general dental practitioners and hospital-based services1, though opinions regarding what constitutes a 'reasonable standard' of referral may vary between dental practitioners and specialists. The quality of referral letters has been the subject of hospital-based research on a number of occasions but there are few if any studies of dental practitioners' views on the constituents of a good referral letter and facilitators or barriers to achieving this.2,3 The reasons for variable quality of referral letters are likely to be complex and simple solutions for improving the situation are not apparent.

Waiting times for oral cancer referrals

Early detection of oral cancer should be a priority, given the excellent prognosis of early stage disease4 and that the waiting time for definitive diagnosis and treatment of people with cancer is a key issue for the NHS. The 1998 white paper 'The New NHS, Modern, Dependable'5 announced new standards for cancer waiting times including a maximum 2 week wait to see a specialist from the time the primary care practitioner decides that an urgent referral is necessary. This was introduced for breast cancer from April 19996 and for all other cancers from 2000.7,8 Head and neck cancers were part of the final tranche of a rolling programme, with December 2000 as the date for achieving the target. The NHS Cancer Plan9, issued in September 2000 underpinned these targets, describing processes by which they might be achieved and monitored. Whilst primary care dental services are nowhere mentioned in these documents, it is unlikely that referrals by dentists for oral cancer diagnosis would be regarded as exempt.

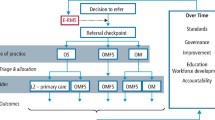

In common with many consultant-led dental services the average waiting time for first patient consultation with the Oral Medicine Service at Birmingham Dental Hospital was far longer than ideal at the time of this study (40 weeks). A fast-track system was in place for referrals where potentially malignant disease was suspected either by the referring practitioner or by one of the consultants following receipt of the referral letter. These patients were offered immediate appointments on the next clinic and, following biopsy, a further appointment was arranged with oncology services within 5 days. This prioritisation was not always possible since many referrals contained insufficient information to allow a judgment of urgency to be made. A precautionary approach was taken to try and avoid patients 'slipping through the net', resulting in a poor specificity for screening referral letters; fewer than 1% of patients positively screened and offered an early appointment were found to have an oral malignancy or pre-malignancy in an audit in 2000 of 88 patients seen over the previous 12 years. This audit also suggested that 11% of patients ultimately found to have malignant disease had not been prioritised as urgent. The potential consequences for patient care are therefore serious. Achieving a more consistent quality of information included with a referral would allow for a more equitable outcome from prioritisation mechanisms, contribute towards improved patient outcomes through earlier diagnosis and treatment and improve service efficiency.

Aim and objectives

A two-phase study was carried out to investigate how the Oral Medicine service at Birmingham Dental Hospital might be improved to allow high priority cases to be better identified and managed appropriately.

The initial phase aimed to assess the quality of referrals from GDPs for patients with a possible oral malignancy. Subsequently, qualitative methodology was used to ascertain GDPs views of the referral process for patients with oral mucosal lesions and factors impacting on this. The purpose of this type of research is to give a deeper explanation and understanding of a problem rather than to quantify it.

Method

Firstly, referral letters from Birmingham GDPs to the Oral Medicine service in the quarter, October to December 2000, were identified from hospital records. The sample was restricted to referrals of red/white patches or other solitary lesions including swellings and ulcers. As the main emphasis of the study was to ascertain practitioners' views on the referral process, a 3-month period was deemed sufficient to identify a range of referral letter quality and therefore an appropriate sample of GDPs.

Criteria for categorising the letters were developed based on both previously published work and the particular needs of the service (Table 1). These were applied in a two-stage process; generic criteria based on the work by McAndrew1 were used as the first stage to identify letters containing basic referral information. However, further information was judged desirable to facilitate the fast-track process and the second stage of the selection process allocated points for this latter type of information; those letters scoring at least five points being deemed to be 'good' referrals. The criteria allocated GDPs into two groups, those meeting (A) and not meeting (B) both stages of the criteria.

During the second phase, qualitative research methodology was used in order to elicit in-depth information from a sample of the GDPs whose letters had been reviewed in the first stage. A purposive sample of practitioners was chosen to represent a range of views from those who did and did not meet the referral criteria, rather than a statistically representative sample and overall, twenty practitioners were selected (ten from group A and ten from group B). Telephone interviews were chosen as the method to be used in order to encourage practitioners to participate in the study, as the time commitment is less than with face-to-face interviews. Despite this, three of the GDPs who were selected to take part in the study were unavailable for interview owing to constraints on their time and were replaced by a further three randomly selected individuals. A semi-structured telephone interview guide was designed and piloted on three GDPs who were not part of the study. The telephone interviews for both groups were carried out by a trained researcher over a period of 1 month and were arranged at times to suit the practitioners, who gave their time freely. The semi-structured interview was designed to last for a maximum of 15 minutes and to collect both demographic practitioner data and the views of those in each group regarding various aspects of patient referral.

Results

Referral letters

A total of 64 relevant referral letters received by the Oral Medicine service between October and December 2000 were identified. Applying the referral letter criteria resulted in approximately equal numbers being allocated to group A (30) and group B (34). However, all referral letters from both groups had scored highly in stage one, with almost all including referring practitioner and patient details. Two thirds of letters were either typed or word-processed and of those hand-written, only two were difficult to read. The main difference between the two groups was in their description of the lesion. Whereas all practitioners in group A had included a detailed description of the lesion, management to date and in some cases, risk factors, those practitioners in group B had only provided a very basic description. As a result of essentially similar interview responses from GDPs in both groups, the interview findings are presented together, although main differences, where present, are highlighted.

Interviews

Overall, 12 (60%) male and 8 (40%) female GDPs were interviewed. Fourteen (70%) of the respondents were local graduates, having qualified in Birmingham. Equal proportions of the group had graduated during the period 1990-2000 and prior to 1990. Just under half (45%) had undertaken some postgraduate training and the majority reported devoting most of their time to NHS care.

Referral

The main perceived barrier to conveying appropriately detailed referral information was a lack of time. Individuals in both groups highlighted a lack of computer facilities and secretarial support. One GDP stated that he would write 'just a basic letter, because I am so busy' and another more recently qualified dentist explained 'When you start out you take a bit more time. My letters usually take me 15–20 minutes as you can't standardly write them and then I have to rewrite them for the receptionist to type them, get them signed and sent off, some dentists may not be able to do this.' Lack of diagnostic confidence was a barrier for some practitioners; one GDP explained that he did not want to commit himself (to a diagnosis) in case he was 'barking up the wrong tree.' However some admitted that the lack of detail in the referral letter may be because 'things were not properly written down when the patient was first seen,' or 'obtaining medical and especially social histories from patients (especially if English is a second language) is difficult.'

The desirability of having guidelines or a proforma was raised and regarded as a factor that could help improve the quality of referrals in both groups. More of the Group B GDPs mentioned the need for postgraduate courses to improve their knowledge. The majority of GDPs suggested that they would rather refer than treat a patient if they felt that they lacked the appropriate skills or knowledge, or if they felt that the patient required specialised care. One practitioner commented, 'As a single handed practice [I] want a second opinion and don't want to take chances' and another that he would refer 'if a pre-malignancy or malignancy is suspected, because the biopsy, diagnosis and treatment will be undertaken in the hospital.'

Referral information

Practitioners were asked what they thought were essential or useful pieces of information to include in their referral letters (Table 2). Generally there was agreement that patient and dentist's details were essential data, but not so as to including a description of the lesion. Almost a third of the dentists (30%) did not think any description of the lesion was essential, and 40% did not regard a detailed description as essential. There appeared to be limited use of clinical photography, although a few practitioners said they would include a photograph of the lesion. Reasons given for not sending photographs with their letters included a lack of facilities or the delay in processing non-digital images. As one practitioner commented 'photos would ideally be used but time would need to be taken to develop the film which may delay the referral.' Interestingly, digital photography was not highlighted as a solution to this problem.

Priority patients

When the practitioners were asked who should be identified as priority patients on the Oral Medicine waiting list, there was general agreement that those with a suspected malignancy, particularly if risk factors are present, should be prioritised. The most common way of referring these priority patients was by telephone, but some GDPs said they would use a referral letter marked 'urgent'. It was felt that some type of index to estimate the likelihood of malignancy might be a useful tool to prioritise patients (in a similar way to prioritisation of orthodontic patients using the IOTN). However, time constraints to undertake detailed assessments were again highlighted.

Quality of service provided by Birmingham Dental Hospital

The majority of practitioners reported that the Oral Medicine service was satisfactory once patients had negotiated the waiting list, but were concerned that there could be delays for urgent referrals. In addition, there was a perception that the service was inflexible and overly dependent on 'paper referrals.' One practitioner commented, 'urgent patients are not prioritised by the hospital service as urgent' and another 'there needs to be some sort of fast-track system.'

The length of the waiting list generally was a source of frustration. In the opinion of one practitioner 'there are problems with the waiting list. I send patients to a general hospital if urgent.' Another reported being told, 'if the patients were to walk in (as an emergency) they would be seen sooner.' It was disappointing that the perception was very far removed from the actual fast-track facility available.

GDPs recommendations for improvement

The overriding view from GDPs was the necessity for shorter waiting times for their patients to see an oral medicine consultant. A typical view was that a method of achieving this would be 'to have more oral specialists and more clinics.' Ways in which the effectiveness of the referral process could be improved were suggested. These included a referral proforma, guidelines or checklist. As one practitioner said, this would be better than a 'long-winded letter' and helpful if the GDP 'did not have the knowledge in the first place.' In addition, having a diagram of the oral cavity, which could be marked to indicate the position of the lesion, was felt to be worthy of consideration. Access to telephone advice and the possibility of using electronic communication were also suggested. Study days and guidelines for practitioners were seen as ways in which practitioners' knowledge of oral mucosal disease could be increased.

Discussion

The standard of referral letters to the Oral Medicine Service at Birmingham Dental Hospital had been identified by the consultants as being of variable quality, thereby frustrating attempts to operate an effective and efficient fast-track process. However, during the first phase of this project, it became apparent that, in fact, essential components of a basic referral letter were being included by the majority of referring practitioners and overall the quality was satisfactory. However, in terms of referral for potential oral malignancy, further information is necessary to enable a judgment to be made as to urgency, in particular a detailed description of the lesion. Approximately half the letters examined did not contain this information.

Despite some indication of differences between the two groups of GDPs, the numbers were too small to make any statistical inferences from the data. However, a higher proportion of practitioners from Group A (the referral letters which 'met' the criteria) had graduated recently and from Birmingham compared with those in Group B (those letters failing to meet the criteria) who tended to be older and graduates of other schools. It could be that group A may have a more recent knowledge of current referral guidelines and be more familiar with the referral system, the local oral medicine consultants and the most appropriate items to include in a referral letter to a particular service.

Although all the practitioners reported being keen to include as much information in referral letters as possible and recognised that descriptions of the lesion and associated risk factors could be regarded as essential details, in practice they were not unanimously including these. Time appeared to be a major barrier to writing effective referral letters, part of a long-winded process, which could be speeded up by having a proforma or specific guidelines. Individuals in both groups highlighted a lack of computer facilities and secretarial support. Furthermore both groups interviewed regarded guidelines or a proforma as factors that could help improve the quality of referrals. More of the Group B practitioners highlighted the need for postgraduate courses to improve their knowledge.

It would appear that very few of the practitioners sampled were aware of the system in place at Birmingham Dental Hospital which enables patients with suspected oral malignancy to be seen on the next clinic, and that the average time for initial consultation, biopsy and oncology appointment is 5 days. Of concern, some GDPs reported referring patients with suspected malignancies to local hospitals due to a perception that they would be seen more quickly. However, this could mean patients being seen in a situation where there is no appropriate specialist service and subsequently being referred to Birmingham Dental Hospital, with further delays. A common theme was that GDPs felt a lack of skills in managing cases themselves, or arriving at a provisional diagnosis. It was a universal view that patients with possible malignant disease should be seen as a priority. Those dentists whose referral letters had scored highly against the criteria tended to report using a variety of methods to alert the Oral Medicine Service if a case was thought urgent. This included writing 'urgent' on the letter and envelope as well as telephoning ahead. Again, this may stem from their practical experience of the way the service operates from their time as students.

All GDPs thought that the oral medicine service could be improved by patients being seen more promptly and increasing the number of oral medicine clinicians providing the service. Referral proformas and a helpline for advice on referrals were identified as processes that would help them include all relevant information and assist with decision making.

Conclusions

A number of GDPs are unaware of the mechanisms in place for handling urgent referrals by the Oral Medicine Service at Birmingham Dental Hospital, which may affect the referral decisions they make, potentially to the detriment of their patients. They appeared to welcome the introduction of educational activities and clearer referral guidance, including a standardised referral proforma such as that available on the Department of Health Website.10 The majority of GDPs did not have access to the internet and some did not have fax machines, making the rapid transmission of such a proforma another issue to be addressed.

Following on from this work, the Oral Medicine Service has formalised the fast track system by introducing and publicising a 'Rapid Access Clinic'. This is protocol driven and requires completion of appropriate proformas that have been distributed to GDPs across the West Midlands, together with explanatory details of the clinic and methods of patient referral.

This was a limited small-scale pilot study relevant to a particular dental hospital and a larger study is indicated over a wider geographical area to ascertain if the issues raised are applicable to oral medicine referrals generally.

References

McAndrew R, Potts AJC, McAndrew M, Adam S . Opinions of dental consultants on the standard of referral letters in dentistry. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 22– 25.

Morris AJ, Burke T . Primary and Secondary Dental Care; the nature of the interface. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 660– 664.

Morris AJ, Burke T . Primary and Secondary Dental Care; how ideal is the interface? Br Dent J 2001; 191: 666– 670.

Sanderson RS, Ironside JAD . Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Br Med J 2002; 325: 822– 827.

Department of Health. The New NHS: Modern, Dependable. Cm3807. HMSO December, 1997.

Department of Health. Breast cancer waiting times – achieving the two week target. Health Service Circular HSC 1998/242, 22/12/1998.

Department of Health. Cancer waiting times; achieving the two week target. Health Service Circular HSC 1999/205, 6/9/1999.

Department of Health. Over 90% of urgent cancer referrals seen within two weeks. Press release 2001/0410, 7/9/2001.

Department of Health. The NHS Cancer Plan, September 2000. (available via www.doh.gov.uk/cancer).

Department of Health. Cancer referral guidelines. HSC 2000/013. 14/4/2000

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by funding from Birmingham Health Authority.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

White, D., Morris, A., Burgess, L. et al. Facilitators and barriers to improving the quality of referrals for potential oral cancer. Br Dent J 197, 537–540 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811800

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4811800

This article is cited by

-

Improving the quality of oral surgery referrals

British Dental Journal (2012)

-

Application of teledentistry in oral medicine in a Community Dental Service, N. Ireland

British Dental Journal (2010)

-

The two-week wait cancer initiative on oral cancer; the predictive value of urgent referrals to an oral medicine unit

British Dental Journal (2006)