Abstract

Objective To examine associations between NHS child dental registration data and area deprivation scores of English Health Authorities (N=100) in 1996/97 and 1997/98.

Method The Department of the Environment index of local conditions and the Jarman Underpriviledge Area Score from the 1991 census were used to measure deprivation. Prior to September 1997, children got free dental treatment under a capitation scheme with an NHS dentist. If they did not attend within 24 months their registration lapsed on the last day of December of the second registration year and they were deleted from the capitation list. After September 1997 the registration period was reduced to 15 months.

Outcome Curve-linear regression of the Health Authority (HA) percentage of children registered, lapses in capitation registrations and deprivation scores.

Results In England 68% of children were registered in December 1996. The percentage registered in each Health Authority was associated with deprivation (DoE, r2=0.33, Jarman, r2=0.27 p<0.01). In January 1997, 17.8% (1,345,142) of children registered lapsed (HA range 12.8% to 30.3%) and this was also significantly associated with deprivation (DoE r2=0.66, Jarman, r2=0.51 p<0.01). Similar results were found in 1997/98.

Conclusions Registration and lapse rates were significantly associated with social deprivation confirming that there is an inverse 'dental' care law for children in England. NHS capitation may widen dental health inequalities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The government public health White Paper, Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation,1 published in July 1999 had two key aims: to improve the health of everyone in the population and to improve the health of the worst off in society by narrowing the health gap. The White Paper recognised that access to healthcare is essential if these aims are to be achieved. The health gap was one reason for the independent inquiry into inequalities in health, chaired by the Chief Medical Officer, Sir Donald Acheson.2 It showed that despite equity of access to care being both a founding principle of the NHS and current government policy, socio-economic factors still account for wide variation in access to primary care, secondary care and mental health services. However, entitlement in law does not always guarantee access to a service as recognised in the inverse care law which was described by a general medical practitioner, Julian Tudor-Hart in 1971.3 'The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served'.

Although Tudor-Hart provided only anecdotal evidence to support his law, subsequent research has proved he was entirely correct.4 The inverse care law also operates in terms of access to services, 'Those with the least need of health care use the health services more, and more effectively, than do those with greatest need'5 which also applies to dentistry. The availability of dental care in Newcastle-upon-Tyne was clearly greater in more affluent areas and poorer in officially designated 'priority' areas.6 This would be an example of an inverse 'dental' care law if we assume, as seems likely, that the distribution of dentists affects availability of care. There is ample evidence of an inverse care law in relation to medicine, but does it apply to dentistry?

Successive guidance has stressed the central role of the general dental practitioner as the preferred provider of dental services in England.7,8 However, previous work has shown an uneven distribution of dentists in the UK by wide variation in dentist/population ratios9 and a clear association between social class of a population and dentist/population ratios.10 A recent report has confirmed that from 1977 to 1995 the distribution of GDPs became more equitable, but that it bore little relation to levels of disease measured by dmft/DMFT and dt/DT in 5 and 12-year-old children.11

As with most diseases, the children with most tooth decay and the greatest need for dental care, are those in the lowest socio-economic group.12 Paradoxically they are also less likely to attend regularly for dental care despite having greater need.

Method

This is a retrospective, cross-sectional, ecological study based on Health Authority areas. It uses routine registration data on the NHS dental services in England and census data collected from the 1991 census.

Children in England get free dental treatment under the NHS and prior to September 1997 individual children were registered under capitation with a NHS dentist for up to 24 months. If they failed to re-attend within the 24-month period their registration lapsed on the last day of December of the second registration year and they were deleted from the capitation list of the dentist. Therefore, if children registered regularly throughout the year, those whose capitation lapsed were registered for an average of 18 months. In September 1997 the capitation registration period was reduced from 24 to 15 months. Using the same assumptions, children whose registration lapsed on the last day of December 1997 were registered for an average of 13.5 months. Under capitation, the dentist received a fee to cover examinations, prevention, emergency care and for fillings which are required to ’secure and maintain oral health’. Certain treatments, e.g. orthodontics and endodontics, are not included under capitation care. This system was subsequently changed to include a weighted fee for dentists working in deprived areas.13

Dental registration data for the 100 Health Authorities (HA) inEngland is regularly published by the English Dental Practice Board (DPB) in quarterly bulletins January to March, April to June, July to September and October to December. This study uses data for under 18 year olds registered under capitation with a NHS dentist from 1993 to 1998. 14 The DPB also published annual reports on changes to capitation registration in 1993 to 1998 and the January capitation figures are derived from this source.15

For the purposes of this study, regular dental attenders aredefined as those with continuous dental registration, i.e. they re-attendedwithin 24 months (or 15 months after January 1998.)Irregular attenders are defined as those whose registration haslapsed or who were not registered. Once individuals are over 18years of age, if their dentist has agreed, they become continuingcare (or adult) patients so are not included in the lapse percent-age.

Two measures of area deprivation were chosen to avoid any biasassociated with a single index. The Department of the Environment(DoE) index of local conditions and Jarman under priviledge area(UPA) score were used as measures of deprivation. They use censusindicators to derive a score with a normal distribution and an Eng-lishHealth Authority average of zero from the 1991 OPCS Census:small area statistics.16 A positive score shows increasing levels ofdeprivation while a negative score shows relatively low levels. They are readily available at Health Authority level from the public health common data set.17

The seven census variables used in the DoE ’index of local conditions’are percentage of:

-

1

Unemployed persons

-

2

Children in low earning households - with no earner or with a’lone parent’ in part-time employment

-

3

Overcrowded households - with more than one person perroom

-

4

Residents in households without basic amenities – lacking or sharing a bath/shower and /or WC, or is non-permanent

-

5

Households without a car

-

6

Children living in unsuitable accommodation – in flats which were not self contained or non-permanent

-

7

17-year-olds no longer in full time education.

The DoE produced their index of local conditions at three spatial scales - Local Authority, electoral ward, and census enumeration district (ED). The index included six indicators at the ED scale, seven at the ward scale, and thirteen at the Local Authority scale. The further six indicators added at the Local Authority level are derived from non-census data sources. As these are not available at the Health Authority level, the index presented here for Health Authorities uses only the seven census indicators.

The eight census variables in the Jarman UPA score are the percentage of:

-

1

Unemployment of head of household

-

2

Elderly living alone

-

3

Social class IV + V

-

4

Single parent households

-

5

Overcrowded households

-

6

Households which have moved in previous 12 months

-

7

Households with children under 5 years of age

-

8

Head of household from new Commonwealth

Significant associations derived from regression models fitted to either percentage capitation registrations or lapses with Health Authority DoE or UPA deprivation scores were used as outcome measures. The aim of the study was to see if an inverse "dental" care law exists with regard to capitation registrations with NHS dentists in England. The null hypothesis was that there was no relationship between either the Health Authority capitation percentage or lapse percentage and the Health Authority DoE or Jarman UPA scores. Statistical significance was taken as p<0.05.

Results

Figure 1 shows the changes in the number of children registered in England between 1993 and 1998. The regular saw-tooth pattern results from the lapse of capitation patients at the end of each year (December 31st). Between December 1993 and January 1996 between 1.32 to 1.43 million children lapsed each year (Table 1). In 1997 the lapse number fell to only 888,000 and may reflect the reduced capitation period from 24 to 15 months

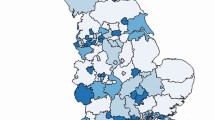

Sixty eight per cent of the English child population registered under capitation in both December 1996 (N=7,577,441 HA range 41% to 82%) and December 1997 (N=7,706,020, HA range 42% to 80%).14 A quadratic (curve linear) regression equation was the model which gave the best approximation to the data (DoE r2=0.33, p<0.01 both years, Jarman 1996 r2=0.27, p<0.01, Jarman 1997 r2 = 0.28, p<0.01) see Tables 2 and 3 and figures 2 and 3. All of the regression models were significant at the p<0.01 level.

Irregular attendance as defined by lapse rate shows that 17.8% of those registered under capitation lapsed in December 1996 (HA range 12.8% to 30.3%).15 This was also significantly associated with the DoE and UPA scores (DoE r2=0.66, p<0.01 Jarman r2=0.51, p<0.01) see tables 2 and 3. However, at the least deprived extreme the percentage of lapsed registrations also rose slightly (see Figure 4). Similarly in December 1997 11.5% lapsed (HA range 7.2% to 21.6%) which was also significantly associated with the deprivation indexes (DoE r2=0.56, p<0.01, Jarman r2=0.40, p<0.01) see Figure 5.

Viewing England as a whole, 68% of the population under 18 years of age were registered and 12.1% of the total population lapsed in December 1996. Therefore by the definitions in the data, only 55.9% of English children were regular attenders and 44.1% were in fact irregular attenders.

Discussion.

The quadratic regression models for both registration and lapse percentages with the deprivation indexes were statistically different from zero and led to the rejection of the null hypothesis. These results support a working hypothesis that there is an inverse 'dental'care law for children in England.

The data used in the analysis has a number of limitations which must be acknowledged. The capitation data is based on the dental practice the children attend and not the area of residence which is used for the census data.

Considering the population as a whole, families with young children are more likely to move house and this may account for a proportion of the lapsed capitation figures. Migration tends to be from areas of unemployment and deprivation to areas of similar or better employment and affluence and has been named the numerator/denominator population bias when mortality rates were considered.18,19 The bias results from the lack of agreement in mortality (the numerator event) and census data which provides the population denominator. Although a numerator/denominator population bias may account for some of the differential in capitation lapses in deprived Health Authorities, census data shows that 7.8% (824,615/10,612,934) of 0–17 year olds in England moved house in the twelve months before the 1991 census.20,21 Even if we assume they all moved to a more affluent area it cannot account for around 18% of the registered under 18 population lapsing. Household migration itself is included as one of the eight variables in the Jarman score and recognises disruption of homelife as a factor in deprivation.

The DoE index of conditions and the Jarman UPA score rely on data from the 1991 census. There are acknowledged problems with coverage of the census – mainly under-enumeration of young adults, mainly men in their 20s as a consequence of homelessness and avoidance of the Poll Tax. The resulting under reporting of unemployment and overcrowding might be expected to be more pronounced in deprived than affluent areas and may have reduced the range of deprivation scores, especially in areas of deprivation. This is likely to favour the null hypothesis but despite this the regression models were still significant.

The data ignores private provision, although for children it is not common except for items of care not available on the NHS and perhaps for children approaching their 18th birthday. Children receive free NHS dental care under capitation and cost may not influence uptake of care except perhaps for indirect costs of parental time off work and travel costs. However, it could be argued that because dental care is free at the point of contact, it is not valued by recipients, is easily available (most dentists will quickly see children in pain) and this may act as a negative influence on the level of registrations. A review of the effectiveness of health service interventions to reduce variations in health concluded 'Whilst removal of financial barriers to accessing health care can make an important contribution to reducing variations in health, this is not in itself sufficient to prevent all avoidable variation.'22

Despite shortcomings with the data the variation in registration lapses was significantly and consistently associated with poverty as measured by two indexes of deprivation and shows that an inverse 'dental' care law exists for children in England. Of more concern was the positive association between lapse percentages and poverty as shown by the increasing lapse rate in deprived areas. With 44.1% of English children defined as irregular dental attenders who we can assume receive little preventive care, a population based preventive approach would be likely to produce a greater benefit. Water fluoridation is widely regarded as the safest and most effective option but even if fluoridation was introduced, to reverse the inverse 'dental' care law, the dental profession, in collaboration with other agencies must target those at the lowest end of the social spectrum to maximise uptake of treatment and preventive dental care and avoid widening the dental health gap. It has been shown that dentists, as independent contractors in the NHS, choose to set up practices in affluent areas.6 The inverse care law was summarised and is largely remembered as: 'The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served.'

However it continues: 'It operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces and less so where such exposure is reduced. The market distribution of medical care is a primitive and historically outdated social form, and any return to it would further exaggerate the maldistribution of medical resources.'

It has been stated that the GDS was set up in 1948 as a system for paying dentists to provide treatment in the NHS. It was not set up as a public health measure and the funding of the GDS is in essence a contract between the public and the dentist.23 Therefore a public health measure aimed at reducing dental health inequalities is, according to the inverse care law, unlikely to be found in the GDS which relies on private finance to establish dental practices. Indeed, the results from this study suggest it may widen dental health inequalities. A dental service aimed at treating those in greatest need is more likely to be a salaried service which could be directed to address inequalities in access to care. Any children currently seen by salaried dental practitioners are already included in the DPB registration figures. The Community Dental Service is also a salaried service and has a complementary role to the GDS7 but as it does not register patients under the NHS system it is not considered in this study. It also remains to be seen if capitation registration in the General Dental Services can be changed via weighted capitation and entry payments for young children in deprived areas.24

One interesting finding is that the best-fit regression lines – (Figures 2345) suggest that the percentage of children registered fell in the most affluent Health Authorities. The small reduction in capitation percentages in the affluent Authorities, suggested by the best fit regression line is unlikely to be statistically significant. However, it may reflect low disease prevalence and little need to access care, or may reflect more use of private dental care.

This study is consistent with research in other branches of medicine which confirms that there is an inverse care law. The results also support a working hypothesis of an inverse 'dental' care law for children in England.

References

Saving lives: our healthier nation. Department of Health, Cm4286, London, Stationary Office, 1999.

Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health. Chairman, Sir Donald Acheson. London, Stationary Office, 1998.

Tudor-Hart J . The Inverse Care Law. The Lancet i: 1971 405–412.

Whitehead M . The Health Divide. London. Penguin 1988.

Whitehead M . Tackling inequalities: a review of policy initiative. In Benzeval M, Judge K; Eds. Tackling inequalities in health an agenda for action. London. Kings Fund 1995.

Carmichael C L . Inner City Britain: A challenge for the dental profession. Review of Dental and Related Deprivation in Inner City Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Br Dent J 1985; 159, 24–27.

The Future Role of the Community Dental Service. Health Circular (89)2 Department of Health. London 1989.

Primary Care Dental Services. Health Services Guidelines Department of Health, London. (97)4 1997.

Scarrott D M, Changes in the regional distribution of general dental service manpower. Br Dent J 1978; 144, 1978. 359–63.

Cook P J and Walker R D . The geographical distribution of dental care in the United Kingdom. Br Dent J 1967; 122: 551–559.

Buck D . Dental health, population size and the distribution of general dental practitioners in England. Community Dent Health 1999 16: 149–153.

Beal J . Social factors and preventive dentistry. In Murray J J ed. The prevention of oral disease. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 3rd edition 1996. pp217–233.

General Dental Services, Amendment 80 to the Statement of Dental Remuneration DoH, London.HSC 1998/042.

GDS Quarterly Statistics. Registrations: England and Wales. Dental Practice Board, Eastbourne 1993 - 1998.

GDS Capitation Registrations. Dental Practice Board, Eastbourne 1993–1998.

Index of Local Conditions (an analysis based on 1991 census data). Department of Environment, 1994.

University of Surrey 1996: Public Health Common Data Set. Brighton. University of Surrey.

Townsend P, Davidson N and Whitehead M . The Black Report. Inequalities in Health: The Black Report and the Health Divide. 2nd Edition, Penguin, London, 1992.

Carstairs V, Morris R . Deprivation and Health in Scotland; 1991. Aberdeen University Press.

1991 Census, Sex, Age and Marital Status 1993, Great Britain. OPCS. HMSO. London.

1991 Census Migration 1994. Great Britain. Part 1, Vol 1. OPCS. HMSO. London.

CRD report 3, Review of the research on the effectiveness of health service interventions to reduce variations in health. NHS centre for reviews and dissemination, The University of York, 1995.

Kravitz T . GDSC Chairman looks forward. British Dental Association News. 1999: 12: 3.

Davies J A . Enhancing dental attendance rates for children from deprived areas in the UK. Br Dent J 1999; 187, 323–326.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mrs C Stirling for secretarial expertise, Dr Z Nugent, Mr L Holden and Mrs M A MacDonald for advice and constructive criticism and Mr K Woods, Director of the North West Dental Public Health Resource Centre. I also acknowledge the comments of the two anonymous referees whose guidance greatly improved the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, C. Capitation registration and social deprivation in England. An inverse 'dental' care law?. Br Dent J 190, 203–206 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800925

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800925

This article is cited by

-

Oral health knowledge, perceptions and practices among parents, guardians and teachers in South Wales, UK: A qualitative study

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Time trends in socio-economic inequalities in the lack of access to dental services among children in Spain 1987-2011

International Journal for Equity in Health (2015)

-

Socio-economic status of patients registered with NHS dental services in Scotland: an inverse 'dental' care law?

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

Targeting dental resources to reduce inequalities in oral health in the North East of England – a health equity audit methodology to evaluate the effects of practice location, practice population and deprivation

British Dental Journal (2010)

-

The future dental workforce?

British Dental Journal (2009)