Key Points

-

Almost one in three young adults (16–24 years) have no fillings

-

Overall, 90% of all dentate adults in 1998 had at least one filling with people on average having seven filled teeth

-

One third of dentate adults in the UK had at least one crown

-

Over one third of those aged 55 and over had root surface fillings

Abstract

People in their late fifties in the UK today can expect to live another 20 years and most want to maintain a functional and aesthetically acceptable dentition. However, 50% of the teeth of dentate adults aged 45 years and over are filled and crowned. The challenges for the dental profession in addressing these aspirations are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The national surveys of Adult Dental Health have given a 10-yearly summary of the clinical condition of adults in the United Kingdom on three previous occasions. The fourth report in the series was published in March of 2000. For the 1998 survey 4,984 addresses were identified at which all adults over 16 in residence were asked to take part in the survey; 21% of households refused and no contact was made at 5% of them. In total, 6,204 adults were interviewed following which those with some teeth were asked to undergo a dental examination; 3,817 (72%) of those eligible agreed. A weighting system based on some of the interview responses of those who consented to be dentally examined and those who were interviewed but not dentally examined was used to reduce bias from non-response. The survey was carried out under the auspices of the Office of National Statistics together with the Universities of Birmingham, Dundee, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Wales.

After being interviewed, adults with some natural teeth were asked whether they would consent to a dental examination in their own home. This paper presents and discusses the results of these examinations in terms of the numbers and distribution of filled teeth, artificial crowns and root surface restorations recorded. Each examiner was trained and calibrated in the diagnostic criteria prior to the survey. Examinations were conducted with adults seated and examiners using illumination from a dental overhead 'Daray' light. A mirror and ball-ended CPI probe were used, but teeth were not dried with compressed air and no radiographs were taken. For each filled or crowned tooth, the examiner was required to indicate the status of the restoration as filled and sound, filled with recurrent caries, or filled with a failed but not carious restoration. For the first time in the accompanying report to this survey,1 crowns were reported separately to fillings. This paper considers each component of adults' dental restorations, ie fillings within the crown, artificial crowns and fillings in the root surfaces and reports the pattern of restorations amongst United Kingdom adults in 1998, as well as discussing how this pattern is likely to change in future generations and the implications of these changes for the dental profession.

Are fillings becoming a feature of middle age?

The decline in dental caries experience amongst children in the United Kingdom and western Europe over the past 20 years is well documented.2 This improvement in child dental health can now be seen in the youngest adult cohort examined in the 1998 survey. Almost 1 in 3 young adults (31% aged 16 to 24 years) have no filled teeth. This is in stark contrast to the next cohort, aged 25 to 34, of whom only 4% have no fillings (Table 1).

Despite the good news in relation to young people, overall 90% of all dentate adults in 1998 had at least one filled tooth with people on average having seven filled teeth. Adults are living longer and keeping their teeth for longer. If we compare 1988 with 1998, the group with the biggest increase in the average number of teeth were people aged 55 and over. They have about two more teeth, from 16.9 in 1988 to 18.8 in 1998. These figures refer only to the dentate population. However, in addition to dentate people having more teeth, substantially more people have any teeth. Therefore, the scale of the increase in the total number of teeth in this population age group is even greater than these average numbers suggest. Since this generation of people had higher disease levels historically, many of the teeth that have been retained have already been filled. In fact, over a third of all the teeth of middle aged adults are filled teeth. Good maintenance and prevention of further disease will be aided if dentists continue to provide restorations of high quality to this age group, as people in their late fifties today have an average life expectancy of another 20 years.

Within England, people living in the least deprived areas have the highest number of restored teeth with an average of 8.6. These people were also the group who were most likely to want to keep their teeth for life. Inevitably, some of these fillings will need replacing in the future. Overall, secondary caries remains the most commonly cited reason for replacing fillings.3,4 However, mechanical failure of both cusps and fillings in previously restored teeth is increasingly reported for middle aged and older adult patients attending dental practice. More practice-based research is indicated in older adults to clarify their likely pattern of restorative failure.

On the positive side, this group of adults are best placed and best motivated to respond to preventive dental care. All these factors suggest that the dental team should be supported and encouraged to place emphasis on prevention of new disease for middle aged and elderly adults, so reducing their potential for developing secondary coronal and root caries.

Who is most likely to have filled teeth?

Women attend the dentist more regularly than men and continue to have more fillings, an average of 7.3 compared with 6.6. Again, the largest difference in who has filled teeth, occurred for those aged between 45 and 64. People in these age groups who attended the dentist for check-ups, either on an occasional or regular basis, had significantly more teeth than those who only attended when they had a dental problem. The result of saving all these teeth has been that dentists have filled rather than extracted many of them, and people who attended for dental check-ups showed that benefit by ending up with most teeth and most fillings (Table 2).

There were differences around the country with higher disease levels in the north and west of the United Kingdom. The biggest contrast was seen in those aged 35 to 44 years. In England, 25% of these adults had 12 or more filled teeth compared with 49% in Northern Ireland (Table 3).

Filled teeth are still more common amongst adults from non-manual backgrounds, but the differences between the social groups has reduced over the past 20 years. People from non-manual backgrounds have reduced their average number of filled teeth from 9.9 in 1978 to 8.9 in 1998. In contrast, those from manual backgrounds have increased their average from 5.9 in 1978 to 6.6 in 1998. One of the contributing factors is likely to be the increase in the proportion of people attending for regular check-ups. In 1978, only 28% of those from unskilled manual backgrounds reported attending regularly compared with 49% in 1998. This change has been much less for those from non-manual backgrounds, from 56% in 1978 to 65% in 1998.

In summary, those who have most filled teeth are people aged 35 years and over, women, people from non-manual backgrounds, and those who reported regular dental attendance.

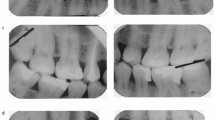

How likely are fillings to be sound and made of amalgam?

The condition of fillings is an important consideration, particularly amongst the middle-aged and elderly dentate people, who have successfully retained their teeth but at the cost of having them filled. During the survey dental examinations, teeth with fillings (or crowns) were classified as sound fillings, unsound fillings or filled with caries. An unsound filling or failed restoration was deemed failed not because of caries, if the restoration was chipped, cracked or had a margin into which a ball-ended probe tip would fit. In general, this meant that all major physical defects were included. The survey will have given an underestimation of teeth with recurrent caries as no radiographs were taken.

Encouragingly, only 4% of all fillings were judged to be mechanically unsound. On average, dentate adults had 7.6 teeth with fillings, 7.1 were judged sound, 0.3 unsound and 0.2 to have further decay. An added bonus was that older people's fillings were no more likely to be judged unsound than fillings in young people.

The overwhelming majority of filled teeth were restored with silver amalgam, 84% of all filled teeth. Of these, only 3% were judged unsound, again with little variation with age.

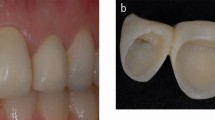

Whose teeth are most likely to be crowned?

One third of dentate adults in the United Kingdom had at least one crowned tooth (34%). Most people with crowns had one or two crowns (20%), but 5% had at least six.

People with most crowns were aged 45 to 54 years and nearly half of that age group had a crown (Fig. 1). Regular attenders in this age group also had an average of three more teeth compared with people who only attend the dentist when they have a problem. In fact, middle aged dentate adults (45 to 64) were nearly 15 times more likely to have a crown than young adults (< 25 years). The effects of a lifetime of dental care may well have contributed to the retention of teeth; albeit in this age group, that to keep these teeth more may have needed to be crowned.

Regular dental attenders had most crowns (40%) compared with those attending only when they have a problem (23%). More women than men had crowns, 37% compared with 31%. However, there were no regional differences and similar numbers of people around the UK had crowns. As might be expected, there were differences between social groups. People living in households headed by those in non-manual occupations were more likely to have crowns (38%) than those from unskilled occupations (28%). The number of people with crowns has increased markedly across all social groups since the 1988 survey, with the largest increase occurring in those from unskilled manual backgrounds.

How common are root surface fillings?

Overall, 15% of dentate adults had root surface filings in 1998. Clearly, the reasons for placement were not known and will be a combination of root surface caries and tooth wear. Inevitably, older people had more root surface fillings with none recorded in those under 25, an average of 0.5 teeth with fillings in those aged 45 to 54 and 1.3 for those aged 65 years and older.

The proportions of people with root surface fillings rose steadily with 35% of 55-64 year olds and 43% of those aged 65 and above (Table 4). The severity rose also, so that many more teeth were affected in the oldest age group with 6% having six or more teeth with root surface fillings. It is salutary to remember that in 1968, only 21% of people aged 65–74 had any teeth compared with 66% in 1998. Tooth retention with advancing years is leading to more complex dental restorative challenges for dentists caring for our aging population.

What are the implications for general dental practitioners in the near future?

To begin to address this question, it is helpful to have a complete picture of restorations in 1998. So far, this paper has considered fillings, crowns and root surface fillings separately. The total number of restorations in the crowns and root surfaces of teeth is given in Table 5 by age group.

Probably, the most useful statistic is the average proportion of restored teeth by age. For those aged 16 to 24 years, only 11% of their teeth are restored. Over the next 10 years, this cohort can be expected to maintain relatively better dental health than the previous generation as expectations and healthy habits continue to improve. Undoubtedly, the key age groups most impacting on dentists' working life will be adults in their middle years.

Other northern European countries are facing similar general and dental demographic profiles, ie an ageing, dentate population.5 In 1999, Norwegian public health dentists examined future demand for dental care in Norway from a macro-economic perspective.6 They predicted that there would be an increase in demand for dental services over the next 10–15 years, with an increasing proportion of elderly dentate people demanding more services. From 2010–15, they felt that picture would change as the younger age groups with fewer fillings get older. However, it should be noted that Scandinavian countries have much narrower differences in wealth (and health) between the richest and poorest people compared with the UK. Of concern, for our own aging UK population will be the continuation of a divide in the health of the elderly and in their economic power to pay for healthcare. In the UK, Richard Scase7 has developed scenarios for 2010 from a social science perspective. His report predicted future over 50s acting younger with a core of 'time rich, cash rich' middle aged consumers. These groups are likely to want to maintain a functional and aesthetically acceptable dentition. However, there will continue to be a significant minority of older adults living in poverty, which may limit their ability to access care. This problem is faced and has been considered for some time in the United States. Those reviewing care of the dentate elderly have suggested that linking dental primary care services with other primary health services like hearing and vision may support future national funding priorities.8 This would put the maintenance and restoration of oral function into an overall context of improving quality of life.

A further note of caution is needed as for some people, longevity will be at the cost of multiple drug regimes or polypharmacy. In 1976, 309 million prescriptions were dispensed compared with 505 million in 1997. Polypharmacy may result in reduced salivary flow and increasing vulnerability to root caries.9 Although more people will retain vigour and good health with age, others will lose their ability for self care as they reach their seventies and eighties but, will still be dentate. The carers of these frail, elderly, dentate adults will need to be shown how to maintain oral hygiene.

In summary, in 1998, 50% of middle aged adults in the UK had teeth with fillings and many will keep these teeth for life. Maintaining these adults' dentitions in good health will continue to be a challenge. This work will require expert technical care to replace failed restorations and the provision of appropriate preventive advice for patients to keep the need for new restorations to a minimum, especially root surface restorations. These twin challenges require different skills and dental practitioners should consider how best both aspects can be delivered within their practice.

Prevention of new root carious lesions will require careful advice on oral hygiene maintenance and a healthy diet.10 Investing in prevention for middle aged and older adults is a new area for dentists and for those funding dental services. Commissioners of dental care will need to recognise that initial costs of prevention may well be greater than treatment costs but investing in maintaining health will not only help older adults to keep their teeth for as long as possible, but will also have a major impact on maintenance costs. There is clearly potential for dental hygienists, therapists and dental health educators to play a part within these more challenging treatment plans.

References

Kelly M, Steele J, Bradnock G . et al. Adult Dental Health. Oral Health in the United Kingdom 1998. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

Pine C M . Community Oral Health. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. 1997.

Pink F E, Minden N J, Simmonds S . Decisions of practitioners regarding placement of amalgam and composite restorations in general practice settings. Oper Dent 1994; 19: 127–132.

Burke F J, Cheung S W, Mjor I A, Wilson N H . Restoration longevity and analysis of reasons for the palcement and replacement of restorations provided by vocational dental practitioners and their trainers in the United Kingdom. Quintessence Int 1999; 30: 234–242.

Kalsbeek H, Truin G J, van Rossum G M, van Rijkom H M, Pooterman J H, Verrips G H . Trends in caries prevalence in Dutch adults between 1983 and 1995. Caries Res 1998; 32: 160–165.

Grytten J, Lund E . Future demand for dental care in Norway; a macro-economic perspective. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol 1999; 27: 321–330.

Scase R . Britain towards 2010. A report of the Foresight Programme Leisure and Learning Panel of the Economic and Social Science Research Council. London: ESRC, 1999.

Jones J A, Adelson R, Niessen L C, Gilbert G H . Issues in financing dental care for the elderly. J Public Health Dent 1990; 50: 268–275.

Jones J A . Root caries: prevention and chemotherapy. Am J Dent 1995; 8: 352–357.

Fedele D J, Sheets C G . Issues in the treatment of root caries in older adults. J Esthet Dent 1998; 10: 243–252.

Acknowledgements

This article has been refereed under the British Dental Journal reviewing process. Full details of sample numbers and the criteria for the clinical examinations can be found in the survey report. We would like to acknowledge the work of Alison Walker, Maureen Kelly and other staff of the Office for National Statistics. This work was undertaken by a consortium comprising the Office for National Statistics and the Dental Schools of the Universities of Birmingham, Dundee, Newcastle and Wales who received funding from the United Kingdom Health Departments; the views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Health Departments nor of the other members of the consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pine, C., Pitts, N., Steele, J. et al. Dental restorations in adults in the UK in 1998 and implications for the future. Br Dent J 190, 4–8 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800868

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800868

This article is cited by

-

Effect of two different primers on the shear bond strength of metallic brackets to zirconia ceramic

BMC Oral Health (2019)

-

Is Periodontitis Prevalence Declining? A Review of the Current Literature

Current Oral Health Reports (2014)

-

Patient choice of primary care practitioner for orofacial symptoms

British Dental Journal (2008)

-

Caries incidence in restorations of shortened lower dental arches – RBBs versus RPDs

British Dental Journal (2001)

-

The use of QLF to quantify in vitro whitening in a product testing model

British Dental Journal (2001)